Lock and key

A lock is a mechanical or electronic fastening device that is released by a physical object (such as a key, keycard, fingerprint, RFID card, security token, coin, etc.), by supplying secret information (such as a number or letter permutation or password), or by a combination thereof or only being able to be opened from one side such as a door chain.

.jpg)

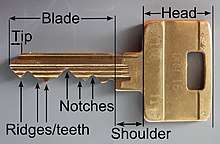

A key is a device that is used to operate a lock (such as to lock or unlock it). A typical key is a small piece of metal consisting of two parts: the bit or blade, which slides into the keyway of the lock and distinguishes between different keys, and the bow, which is left protruding so that torque can be applied by the user. In its simplest implementation, a key operates one lock or set of locks that are keyed alike, a lock/key system where each similarly keyed lock requires the same, unique key.

The key serves as a security token for access to the locked area; only persons having the correct key can open the lock and gain access. In more complex mechanical lock/key systems, two different keys, one of which is known as the master key, serve to open the lock. Common metals include brass, plated brass, nickel silver, and steel.

History

Antiquity

The earliest known lock and key device was discovered in the ruins of Nineveh, the capital of ancient Assyria.[1] Locks such as this were later developed into the Egyptian wooden pin lock, which consisted of a bolt, door fixture or attachment, and key. When the key was inserted, pins within the fixture were lifted out of drilled holes within the bolt, allowing it to move. When the key was removed, the pins fell part-way into the bolt, preventing movement.[2]

The warded lock was also present from antiquity and remains the most recognizable lock and key design in the Western world. The first all-metal locks appeared between the years 870 and 900, and are attributed to the English craftsmen.[3] It is also said that the key was invented by Theodorus of Samos in the 6th century BC.[1]

'The Romans invented metal locks and keys and the system of security provided by wards.'[4]

Affluent Romans often kept their valuables in secure locked boxes within their households, and wore the keys as rings on their fingers. The practice had two benefits: It kept the key handy at all times, while signaling that the wearer was wealthy and important enough to have money and jewellery worth securing.[5]

A special type of lock, dating back to the 17th-18th century, although potentially older as similar locks date back to the 14th century, can e.g. be found in the Beguinage of the Belgian city Lier.[6][7] These locks are most likely Gothic locks, that were decorated with foliage, often in a V-shape surrounding the keyhole.[8] They are often called drunk man's lock, however the reference to being drunk may be erroneous as these locks were, according to certain sources, designed in such a way a person can still find the keyhole in the dark, although this might not be the case as the ornaments might have been purely aesthetic.[6][7] In more recent times similar locks have been designed.[9][10]

Modern locks

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century and the concomitant development of precision engineering and component standardization, locks and keys were manufactured with increasing complexity and sophistication.

The lever tumbler lock, which uses a set of levers to prevent the bolt from moving in the lock, was invented by Robert Barron in 1778. His double acting lever lock required the lever to be lifted to a certain height by having a slot cut in the lever, so lifting the lever too far was as bad as not lifting the lever far enough. This type of lock is still used today.[11]

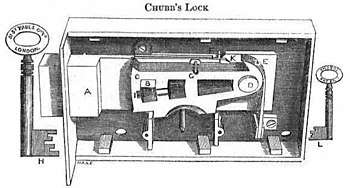

The lever tumbler lock was greatly improved by Jeremiah Chubb in 1818. A burglary in Portsmouth Dockyard prompted the British Government to announce a competition to produce a lock that could be opened only with its own key.[5] Chubb developed the Chubb detector lock, which incorporated an integral security feature that could frustrate unauthorized access attempts and would indicate to the lock's owner if it had been interfered with. Chubb was awarded £100 after a trained lock-picker failed to break the lock after 3 months.[12]

In 1820, Jeremiah joined his brother Charles in starting their own lock company, Chubb. Chubb made various improvements to his lock: his 1824 improved design didn't require a special regulator key to reset the lock; by 1847 his keys used six levers rather than four; and he later introduced a disc that allowed the key to pass but narrowed the field of view, hiding the levers from anybody attempting to pick the lock.[13] The Chubb brothers also received a patent for the first burglar-resisting safe and began production in 1835.

The designs of Barron and Chubb were based on the use of movable levers, but Joseph Bramah, a prolific inventor, developed an alternative method in 1784. His lock used a cylindrical key with precise notches along the surface; these moved the metal slides that impeded the turning of the bolt into an exact alignment, allowing the lock to open. The lock was at the limits of the precision manufacturing capabilities of the time and was said by its inventor to be unpickable. In the same year Bramah started the Bramah Locks company at 124 Piccadilly, and displayed the "Challenge Lock" in the window of his shop from 1790, challenging "...the artist who can make an instrument that will pick or open this lock" for the reward of £200. The challenge stood for over 67 years until, at the Great Exhibition of 1851, the American locksmith Alfred Charles Hobbs was able to open the lock and, following some argument about the circumstances under which he had opened it, was awarded the prize. Hobbs' attempt required some 51 hours, spread over 16 days.

The earliest patent for a double-acting pin tumbler lock was granted to American physician Abraham O. Stansbury in England in 1805,[14] but the modern version, still in use today, was invented by American Linus Yale Sr. in 1848.[15] This lock design used pins of varying lengths to prevent the lock from opening without the correct key. In 1861, Linus Yale Jr. was inspired by the original 1840s pin-tumbler lock designed by his father, thus inventing and patenting a smaller flat key with serrated edges as well as pins of varying lengths within the lock itself, the same design of the pin-tumbler lock which still remains in use today.[16] The modern Yale lock is essentially a more developed version of the Egyptian lock.

Despite some improvement in key design since, the majority of locks today are still variants of the designs invented by Bramah, Chubb and Yale.

Types of lock

- Bicycle lock

- Cam lock

- Chamber lock

- Child safety lock

- Chubb detector lock

- Combination lock

- Cylinder lock

- Dead bolt

- Electric strike

- Electronic lock

- Lever tumbler lock

- Lock screen

- Luggage lock

- Magnetic keyed lock

- Magnetic lock

- Mortise lock

- Padlock

- Pin tumbler lock

- Police lock

- Protector lock

- Rim lock

- Time lock

With physical keys

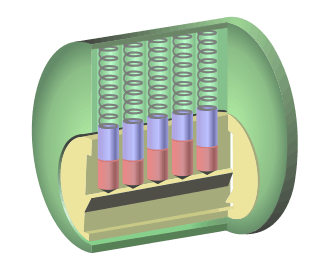

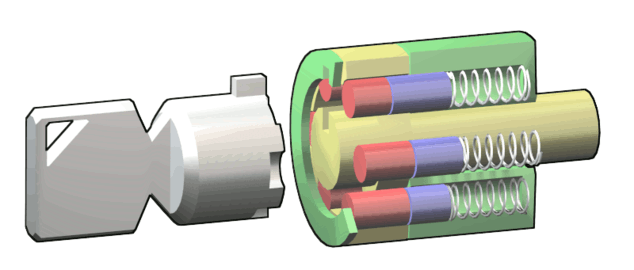

Pin tumbler lock: without a key in the lock, the driver pins (blue) are pushed downwards, preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating. An additional pin called the master pin is present between the key and driver pins in locks that accept master keys to allow the plug to rotate at multiple pin elevations.

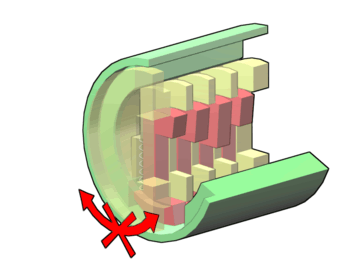

Pin tumbler lock: without a key in the lock, the driver pins (blue) are pushed downwards, preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating. An additional pin called the master pin is present between the key and driver pins in locks that accept master keys to allow the plug to rotate at multiple pin elevations. Wafer tumbler lock: without a key in the lock, the wafers (red) are pushed down by springs. The wafers nestle into a groove in the lower part of the outer cylinder (green) preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating.

Wafer tumbler lock: without a key in the lock, the wafers (red) are pushed down by springs. The wafers nestle into a groove in the lower part of the outer cylinder (green) preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating. Tubular lock: the key pins (red) and driver pins (blue) are pushed towards the front of the lock, preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating. The tubular key has several half-cylinder indentations which align with the pins.

Tubular lock: the key pins (red) and driver pins (blue) are pushed towards the front of the lock, preventing the plug (yellow) from rotating. The tubular key has several half-cylinder indentations which align with the pins.

A warded lock uses a set of obstructions, or wards, to prevent the lock from opening unless the correct key is inserted. The key has notches or slots that correspond to the obstructions in the lock, allowing it to rotate freely inside the lock. Warded locks are typically reserved for low-security applications as a well-designed skeleton key can successfully open a wide variety of warded locks.

The pin tumbler lock uses a set of pins to prevent the lock from opening unless the correct key is inserted. The key has a series of grooves on either side of the key's blade that limit the type of lock the key can slide into. As the key slides into the lock, the horizontal grooves on the blade align with the wards in the keyway allowing or denying entry to the cylinder. A series of pointed teeth and notches on the blade, called bittings, then allow pins to move up and down until they are in line with the shear line of the inner and outer cylinder, allowing the cylinder or cam to rotate freely and the lock to open.

A wafer tumbler lock is similar to the pin tumbler lock and works on a similar principle. However, unlike the pin lock (where each pin consists of two or more pieces) each wafer is a single piece. The wafer tumbler lock is often incorrectly referred to as a disc tumbler lock, which uses an entirely different mechanism. The wafer lock is relatively inexpensive to produce and is often used in automobiles and cabinetry.

The disc tumbler lock or Abloy lock is composed of slotted rotating detainer discs.

The lever tumbler lock uses a set of levers to prevent the bolt from moving in the lock. In its simplest form, lifting the tumbler above a certain height will allow the bolt to slide past. Lever locks are commonly recessed inside wooden doors or on some older forms of padlocks, including fire brigade padlocks.

A magnetic keyed lock is a locking mechanism whereby the key utilizes magnets as part of the locking and unlocking mechanism. A magnetic key would use from one to many small magnets oriented so that the North and South poles would equate to a combination to push or pull the lock's internal tumblers thus releasing the lock.

With electronic keys

An electronic lock works by means of an electric current and is usually connected to an access control system. In addition to the pin and tumbler used in standard locks, electronic locks connects the bolt or cylinder to a motor within the door using a part called an actuator. Types of electronic locks include the following:

A keycard lock operates with a flat card of similar dimensions as a credit card. In order to open the door, one needs to successfully match the signature within the keycard.

The lock in a typical remote keyless system operates with a smart key radio transmitter. The lock typically accepts a particular valid code only once, and the smart key transmits a different rolling code every time the button is pressed. Generally the car door can be opened with either a valid code by radio transmission, or with a (non-electronic) pin tumbler key. The ignition switch may require a transponder car key to both open a pin tumbler lock and also transmit a valid code by radio transmission.

A smart lock is an electromechanics lock that gets instructions to lock and unlock the door from an authorized device using a cryptographic key and wireless protocol. Smart locks have begun to be used more commonly in residential areas, often controlled with smartphones.[17][18] Smart locks are used in coworking spaces and offices to enable keyless office entry.[19] In addition, electronic locks cannot be picked with conventional tools.

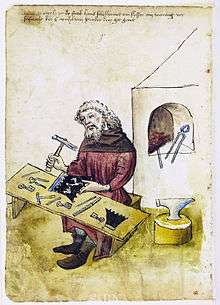

Locksmithing

Locksmithing is a traditional trade, and in most countries requires completion of an apprenticeship. The level of formal education required varies from country to country, from no qualifications required at all in the UK,[20] to a simple training certificate awarded by an employer, to a full diploma from an engineering college. Locksmiths may be commercial (working out of a storefront), mobile (working out of a vehicle), institutional, or investigational (forensic locksmiths). They may specialize in one aspect of the skill, such as an automotive lock specialist, a master key system specialist or a safe technician. Many also act as security consultants, but not all security consultants have the skills and knowledge of a locksmith.

Historically, locksmiths constructed or repaired an entire lock, including its constituent parts. The rise of cheap mass production has made this less common; the vast majority of locks are repaired through like-for-like replacements, high-security safes and strongboxes being the most common exception. Many locksmiths also work on any existing door hardware, including door closers, hinges, electric strikes, and frame repairs, or service electronic locks by making keys for transponder-equipped vehicles and implementing access control systems.

Although the fitting and replacement of keys remains an important part of locksmithing, modern locksmiths are primarily involved in the installation of high quality lock-sets and the design, implementation, and management of keying and key control systems. Locksmiths are frequently required to determine the level of risk to an individual or institution and then recommend and implement appropriate combinations of equipment and policies to create a "security layer" that exceeds the reasonable gain of an intruder.

Key duplication

Traditional key cutting is the primary method of key duplication. It is a subtractive process named after the metalworking process of cutting, where a flat blank key is ground down to form the same shape as the template (original) key. The process roughly follows these stages:

- The original key is fitted into a vise in a machine, with a blank attached to a parallel vise which is mechanically linked.

- The original key is moved along a guide in a movement which follows the key's shape, while the blank is moved in the same pattern against a cutting wheel by the mechanical linkage between the vices.

- After cutting, the new key is deburred by scrubbing it with a metal brush to remove particles of metal which could be dangerously sharp and foul locks.

Modern key cutting replaces the mechanical key following aspect with a process in which the original key is scanned electronically, processed by software, stored, then used to guide a cutting wheel when a key is produced. The capability to store electronic copies of the key's shape allows for key shapes to be stored for key cutting by any party that has access to the key image.

Different key cutting machines are more or less automated, using different milling or grinding equipment, and follow the design of early 20th century key duplicators.

Key duplication is available in many retail hardware stores and as a service of the specialized locksmith, though the correct key blank may not be available. More recently, online services for duplicating keys have become available.

Symbolism

Heraldry

Keys appear in various symbols and coats of arms, the best-known being that of the Holy See – derived from the phrase in Matthew 16:19 which promises Saint Peter, in Roman Catholic tradition the first pope, the Keys of Heaven. But this is by no means the only case. Many examples are given on Commons.

References

- de Vries, N. Cross and D. P. Grant, M. J. (1992). Design Methodology and Relationships with Science: Introduction. Eindhoven: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 32. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24.

- Ceccarelli, Marco (2004). International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 43. ISBN 1402022034. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24.

- "History". Locks.ru. Archived from the original on 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- "Key | lock device". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

- "History". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-12-09. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- R. De Bruyn, ‘Oude sloten op deurtjes in het Liers begijnhof’, in: 't land van Ryen jaargang 17, aflevering 3-4, 1967, p.158,, article in Dutch

- Echtpaar schrijft eerste boek sinds twintig jaar over Liers begijnhof nieuwsblad.be, Chris van Rompaey, 17 april 2018, article in Dutch

- Dictionary, Lexicon of locks and keys historicallocks.com

- United States patent keyhole guide for locks and method of using the same patentimages, Eugene Toussant, 1990

- V-Lock Helps Drunks Get Home to Bed wired.com, Charlie Sorrel, 5 april 2010

- Pulford, Graham W. (2007). High-Security Mechanical Locks : An Encyclopedic Reference. Elsevier. p. 317. ISBN 0-7506-8437-2.

- "Lock Making: Chubb & Son's Lock & Safe Co Ltd". Wolverhampton City Council. 2005. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- Roper, C.A. & Phillips, Bill (2001). The Complete Book of Locks and Locksmithing. McGraw-Hill Publishing. ISBN 0-07-137494-9.

- The Complete Book of Home, Site, and Office Security: Selecting, Installing, and Troubleshooting Systems and Devices. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2016-11-21.

- The Geek Atlas: 128 Places Where Science and Technology Come Alive. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 445. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- "Inventor of the Week Archive". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2013-05-29.

- "Ditch the keys: it's time to get a smart lock". Popular Mechanics. 26 November 2013. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Kisi And KeyMe, two smart phone apps, might make house keys obsolete". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Kurutz, Steven. "Losing The Key". The New York Times. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "What qualifications do I need to be a locksmith?". Master Locksmiths Association. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

Further reading

- Phillips, Bill. (2005). The Complete Book of Locks and Locksmithing. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-144829-2.

- Alth, Max (1972). All About Locks and Locksmithing. Penguin. ISBN 0-8015-0151-2

- Robinson, Robert L. (1973). Complete Course in Professional Locksmithing Nelson-Hall. ISBN 0-911012-15-X

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Lock and key |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Locks (security devices). |

- Historical locks by Raine Borg and ASSA ABLOY

- Picking Locks Popular Mechanics