Locality (linguistics)

In linguistics, locality refers to the proximity of elements in a linguistic structure. Constraints on locality limit the span over which rules can apply to a particular structure. Theories of transformational grammar use syntactic locality constraints to explain restrictions on argument selection, syntactic binding, and syntactic movement.

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Where locality is observed

Locality is observed in a number of linguistic contexts, and most notably with:

- Selection of arguments; this is regulated by the projection principle

- Binding of two DPs; this is regulated by binding theory

- Displacement of wh-phrases; this is regulated by wh-movement

Selection

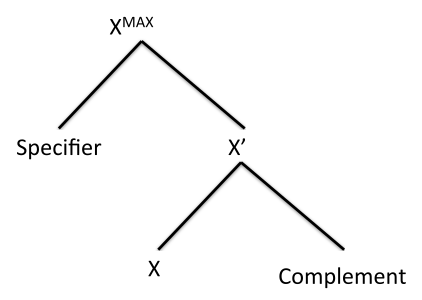

The projection principle requires that lexical properties — in particular argument structure properties such as thematic roles — be "projected" onto syntactic structures. Together with Locality of Selection, which forces lexical properties to be projected within a local projection (as defined by X-bar theory[1]:149), the projection principle constrains syntactic trees. Syntactic trees are represented through constituents of a sentence, which are represented in a hierarchical fashion in order to satisfy locality of selection through the restraints of X-bar theory.[2] In X-bar theory, immediate dominance relations are invariant, meaning that all languages have the same constituent structure. However, the linear precedence relations can vary across languages. For example, word order (i.e. constituent order) can vary with and across languages.[1]

| Locality of Selection |

|---|

| Every argument that α selects must appear in the local domain of α. |

If α selects β, then β depends on α. If α selects β, and if locality of selection is satisfied, then α and β are in a local dependency. If α selects β, and if locality of selection is not satisfied, then α and β are in a non-local dependency. The existence of a non-local dependency indicates that movement has occurred.

From the perspective of projection, an element can be "stretched" to occupy the following projection levels:

minimal (X)

intermediate (X')

maximal (X max)

These occupying elements appear valid for all syntactically relevant lexical and functional categories.[3]

Head-Complement Selection

According to locality of selection, the material introduced in the syntactic tree must have a local relationship with the head that introduces it. This means that each argument must be introduced into the same projection as its head. Therefore, each complement and specifier will appear within the local projection of the head that selects it.

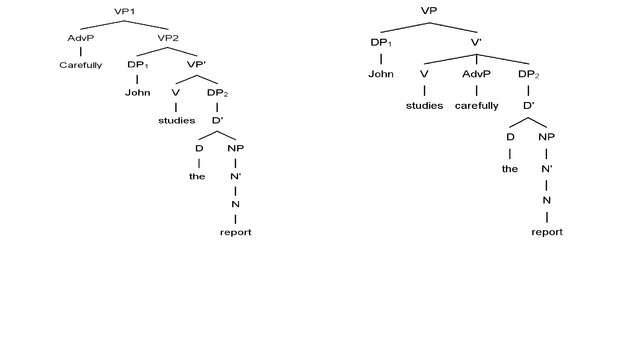

For example, the contrast between the well-formed (1a) and the ill-formed (1b) shows that in English, an adverb cannot intervene between a head (the verb study) and its complement (the DP the report).

(1) a. John carefully [V studies] [DP the report].

b. *John [V studies] carefully [DP the report].[1]:192 |

In structural accounts of the contrast between (1a) and (1b), the two sentences differ relative to their underlying structure. The starting point is the lexical entry for the verb study, which specifies that the verb introduces two arguments, namely a DP which bears the semantic role of Agent, and another DP which bears the semantic role of Theme.

lexical entry for study: V, <DPAGENT,DPTHEME>

In the tree for sentence (1a), the verb, studies, is the Head of the VP projection, the DPTHEME, the report, is projected onto the Complement position (as sister to the head V), and the DPAGENT , John, is projected onto the Specifier (as sister to V'). In this way, (1a) satisfies Locality of Selection as both arguments are projected within the projection of the head that introduces them. The adverb phrase, AdvP carefully attaches as an unselected adjunct to VP; structurally this means that it is outside of the local projection of V as it is sister to and dominated by VP. In contrast, in the tree for sentence (1b), the introduction of the AdvP carefully as sister to the verb study violates Locality of Selection; this is because the lexical entry of the verb study does not select an AdvP, so the latter cannot be introduced in the local projection of the verb.

Morphological selection

Locality can also be broken down into a morphological perspective, by analyzing words with some, or many affixes. A speaker who can make sense of a word with many morphemes (e.g. affixes) must know: how the morpheme is pronounced and what kind of morpheme it is, (free, prefix, suffix). If it is an affix, then the speaker also must know what the affix c-selects. The speaker must also know that the c-selected element must be adjacent to the affix, amounting to the requirement that branches of a tree never cross. Crossing branches is not included in the lexicon, and it is a general property of how linguistic structures are grammatically structured. This is true because lexical entries do no impose a requirement on a part of word structure that it is not sister to. This relates to the fact that affixes cannot c-select for an element which is not a sister. Additionally, the speaker must know what kinds of thing results after c-selection. These key aspects that a speaker must know can be observed in the lexical entries below, with the example "denationalization".

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| nation: | free | ||

| -al: | suffix | c-selects N | to form an A |

| -ize: | prefix | c-selects A | to form a V |

| -de: | prefix | c-selects V | to form a V |

| -ation: | suffix | c-selects V | to form an N |

Lexical selection

When meeting selection requirements, the semantic content of the constituent selected by the head must be taken into consideration. For example, the thematic role of the constituent that is selected, and the properties of the head which selects it. Take, for example, the verb head elapse, which selects for a DP subject.

E.g. a) *[DP Johnagent] elapsed.

b) [DP Timeagent, can elapse] elapsed.[4]

However, while [DP John] is syntactically in subject position, it gives an ungrammatical sentence as [DP John] cannot elapse, it has no thematic quality to elapse, and as such cannot meet the lexical selection requirements of [VP elapse]. However, [DP Time] in subject position does have this thematic quality and can be selected by [VP elapse].

Lexical selection is specific to individual word requirements, these must abide to both Projected Principle and Locality requirements.

Detecting Selection

Crucially, selection determines the shape of syntactic structures. Selection takes into consideration not only lexical properties but also constituent selection, that is what X-Bar Theory predicts as appropriate formulations for specific constituents.

Covariation

One way to determine which syntactic items relate to each other within the tree structure is to examine covariences of constituents. For example, given the selectional properties of the verb elapse, we see that not only does this verb select for a DP subject, but is specific about the thematic role this DP subject must have.[2]

Case

In English, case relates to properties of the pronoun, nominative, accusative, and genitive. Case can be selected by heads within the structure, and this can affect the syntactic structure expressed in the underlying and surface structure of the tree.[2]

EPP Properties

EPP properties, or Extended Projection Principle, is located in certain syntactic items, which motivate movement due to their selection requirements. Such can be found most commonly in T, which in English, requires a DP subject. This selection by T creates a non-local dependency, and leaves behind a 'trace' of the moved item.[2]

Binding

Binding Theory refers to 3 different theoretic principles that regulate DP's (Determiner Phrase).[3] In consideration of the following definitions of the principles, the local domain refers to the closest XP with a subject. If a DP(1) is bound, this means it is c-commanded and co-indexed by a DP(2) that is sister to the XP dominating over DP (1) .To contrast, if it is free, then the DP in question must not be c-commanded and co-indexed by another DP.

Principle A

Principle A for locality in Binding Theory refers to the binding of an anaphor and its antecedent which must occur within its local domain. Principle A states that anaphors must be bound in their local domain, and that DP's must be in a local relation. The local domain is the smallest XP containing a DP, in order to satisfy Binding Theory, the DP must c-command the anaphor and have a subject.[1] Therefore, the antecedent must be in the same clause that contains the anaphor if it is to abide to Binding Theory.

An anaphor is considered to be free when it is not c-commanded or co-indexed.[5] A node is c-commanded if a sister node of the first node dominates it, (i.e. node X c-commands node Y if a sister of X dominates Y). A node is co-indexed if the DPs in question both are indexed by a matching subscript letter, as seen in the DPs of (2) a. and (2) b.

In English, Principle A governs over anaphors, which include lexical items like reflexives, (e.g. myself, yourself...etc.), and reciprocals, (e.g. each other, etc.). These items must refer back to a previous item in the constituent in order to satisfy its semantic meaning, and in turn, abide to Principle A.

The following examples show the application of Binding Theory, Principle A, in relation to reflexives:

(2) a. Mary revealed [DP John]i to [DP himself]i.

b. *Mary revealed [DP himself]i to [DP John]i.[1]:162 |

_2a.png)

Example (2a) is predicted to be grammatical by Principle A of binding theory. The anaphor, [DP himself]i, and antecedent, [DP John]i, are selected within the same local domain. TP is the smallest XP that contains the anaphor and DP subject (in this case, the subject is the antecedent). Given that the antecent, [DP John]i, is governed by VP, which is sister to PP, and PP is the maximal node dominating over [DP himself]i, the anaphor, [DP John]i can therefore c-command [DP himself]i. As co-indexation is already established by the matching subscript letter i, this sentence is grammatical and abides to Principle A.

_2b.png)

However, in example (2b), the anaphor [DP himself]i has within its local domain antecedent, [DP Mary], which would serve as a candidate for binding. However, [DP himself]i is co-indexed to [DP John]i, which is a pronoun. Two factors have gone wrong here. Firstly, as shown in Principle B below, pronouns must be free in their local domain, and as [DP John]i is being bound locally by [DP himself]i, this does not abide to Binding Theory and is considered ungrammatical. Secondly, and most important to this section, Principle A establishes that an anaphor must be bound locally. [DP himself]i is not c-commanded by any local DP, nor any DP, in fact, [DP himself]i is c-commanding [DP John]i instead.

As discussed previously, the local DP which could bind [DP himself]i, [DP Mary]. However, while [DP Mary] can c-command [DP himself]i, and can be co-indexed to complete binding, this sentence would still be ungrammatical. This is because, in English, anaphors and their antecedent must agree in gender. As such, attempting to fix 2b by binding [DP himself]i with [DP Mary] would still render an ungrammatical sentence.

This is exemplified below:

Attempted correction of (2b)

i) *[DP Mary]i revealed [DP himself]i to [DP John]

ii) [DP Mary]i revealed [DP herself]i to [DP John]

The following examples show the application of Binding Theory, Principle A, in relation to reciprocals:

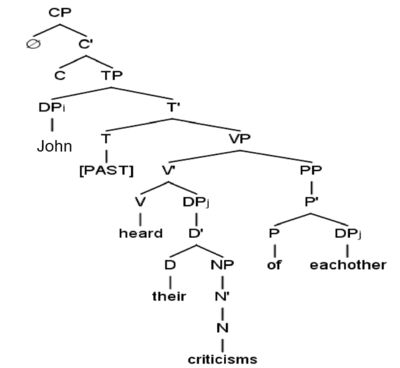

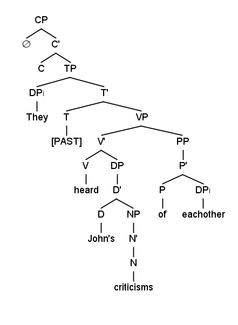

(3) a. John heard [DP their]i criticisms of [DP each other]i.

b. *[DP They]i heard John's criticisms of [DP each other]i.[1]:167 |

Example (3) follows the same explanations to example (2).

As predicted by Binding Theory, Principle A, (3a) is grammatical because the anaphor [DP each other]i is bound within the same domain as the antecedent [DP their]i. However, example (3b) is ungrammatical because the anaphor is bound by the antecedent non-locally, which goes against Principle A which specifies local binding. Further, Principle A would predict that in fact it is [DP John] which could bind [DP each other]i, however, similarly to example 2b, anaphors not only have to agree with gender with the antecedent that binds them, but also number. Given that [DP John] is a singular entitiy, and [DP each other] refers to multiple, this co-indexation cannot occur, rendering this sentence ungrammatical.

To summarize, it must be noted that anaphos must agree in gender, number, and also person with their antecedent, in a local domain.

Principle B

Principle B states: pronouns must be free in their local domain, and predicts that some DP's are non-locally bound to other DP's.

Take for example, these two sentences:

| (4) a. *[DP Lucy]i admires [DP her]i

b. [DP Lucy]i thinks that I admire [DP her]i |

In 4a), when the [DP Lucy], is co-indexed with, and c-commands, [DP her], this violates principle B. This is because [DP her] has a c-commanding antecedent in its local domain (i.e. [DP Lucy]) this shows that the pronoun is bound in its domain. As such, pronoun [DP Lucy], which also abides to principle B, also cannot be bound locally, and contributes to the sentences problems with abiding to Principle B.

In (4b) Principle B is obeyed, this is because while there is co-indexation and a c-commanding relation between [DP Lucy] and [DP her], both DPs are free in their local domains. Remember that local domain is determined by the smallest XP containing a subject. In the case of [DP Lucy], the local domain pertains to the head which dominates it, of which [DP Lucy] is the subject, while for [DP her], it would be the smallest XP containing a subject, which is [DP I].

Principle B does not state anything regarding whether a pronoun requires an antecedent. It is permissible for a pronoun to not have an antecedent in a sentence. Principle B simply states that if a pronoun does have a c-commanding antecedent, then it must be outside of the smallest XP with a subject that has the pronoun, i.e. outside the domain of the pronoun.[1] Further, both Principle A and B predict that pronouns and anaphos must occur in complementary distribution.

Principle C

The following examples show the application of Binding Theory, Principle C which states: R-expressions cannot be bound, and certain DP's, such as R-expressions are never related to other DP's.[1]

In English, R-expressions refer to Quantified Expressions,[2] (e.g. every, all, some...etc.) and Independently Referential Expressions,[2] (e.g. this, the, my, a, pronouns)

| (5) a. *[DP She]i said that [DP Lucy]i took the car

b) After you spoke to [DPher]i, [DPLucy]i took the car c) The builder of [DPher]i house visited [DPLucy]i[2] |

|---|

It is important to note that 5a, can be distinguished from 5b and 5c the differences in structural relations between the pronoun and the name. In 5a, "she" c-commands "Lucy", but this does not occur in 5b and 5c. These observations can be described by the preliminary observation that non-pronominals cannot be bound, i.e., non-pronominals cannot be c-commanded by a co-indexed pronoun. Compared to Principle A and Principle B, this requires goes all the way up to the root node, since it is not limited to any domain.

In addition to these principles, it is required that pronouns and reflexives agree with their antecedent in gender. For example, regardless of the consideration of locality, a sentence such as "[DPJohn]i likes [DPherself]i", it would be ungrammatical because the two co-indexed entities do not agree in gender. Pronouns and reflexives also have to agree with their antecedent in number and person.

Small Clauses and Binding Theory

Small clauses show that different categories can have subjects, which is supported by Binding Theory. The internal structure of a small clause is determined, typically, by a predicate or a functional element, and are considered as being projections of a functional category.[6]

Given this, Binding Theory can predict the internal structure of a small clause, depending on which Principle is present within the structure.

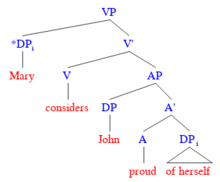

Take, for example, the following data:

| 5.1 a) | *[DP Mary]j considers [John proud of [DP herself]j][2] | ||

| 5.1 b) | [DP Mary]j considers [John proud of [DP her]j]][2] | ||

This data suggests that [AP proud] has a subject, [DP John], and that the anaphor that it has as a complement, [DP herself]/[DP her], has a domain local domain that extends to the node which dominates [DP Mary], as it c-commands and binds the anaphor.[2]

As such, the underlying structure that is suggested is the following:

_.png)

Binding Theory correctly predicts that 5.1 a) will be an ungrammatical construction given Principle A which requires the anaphor to be bound locally. As well as correctly predicting 5.1 b) as grammatical, given Principle B, which states that pronouns cannot be locally bound. Both instances are represented, respectively, within the generated structures.

Syntactic dependencies

Syntactic dependencies of all types are confined to a limited portion of structure.[7] Referential and filler gap-dependencies remain a divide in locality principles. Few theories which have succeeded in unifying these two types of dependencies undel locality principles. While there is no agreed-upon theory, general observations are seen. Absolute and relative barriers are a great divide in locality theory and have yet to be formally unified under a single theory.[7]

Absolute barriers do not allow movement beyond it. (WH-island, Subjacency conditions and Condition on Extraction Domain)

Relative barrier is the idea that syntactic dependencies between a filler and a gap are blocked by the intervention of a closer element of the same type

Movement

Movement is the phenomenon that accounts for the possibility of a single syntactic constituent or element occupying multiple, yet distinct locations, depending on the type of sentence the element or constituent is in.[8] Movement is motivated by selection of certain word types, which require their Projection Principles be met Locally. In short, Locality predicts movement of syntactic constituents.

Raising to Subject: Surface and Underlying Tree Structure

When comparing surface structure to what selection predicts, there appears to be an anomaly in the word order of the sentence and the production of the tree. Within the underlying structure, at times referred to as deep structure, there exist Deep Grammatical Relations, which relate to the manifestation of subject, object and indirect object.[9] Deep grammatical relations are mapped onto the underlying structure, (deep structure). These are expressed configurationally in relevance to particular languages, and are seen represented in the surface representation of the syntactic tree. This surface representation is motivated by selection, locality, and item specific features which allow for movement of syntactic items.

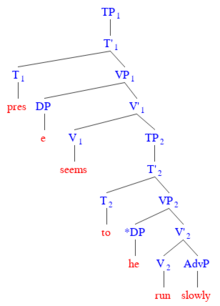

Take for example the following sentence:

- [DP He] [VP seems] to[VP run] slowly

Given the word order of the sentence, we would expect the tree to have violated Locality of Selection and Projection Principle guidelines. Projection Principle specifies what the head selects for, and Locality of selection ensures that these are established in the local domain of the head which selects it.

As such, we would expect the following ungrammatical tree:

This tree represents local dependencies of selection. [VP run] selecs for a DP subject and can have an AdvP complement, this is satisfied. However, [VP seems] also requires a DP subject, which is unsatisfied. Lastly, T has an EPP feature, as discussed above, which selects for a DP subject. It's these selectional properties which motivate movement of certain syntactic items. In this particular tree, it is the DP which is motivated to move, in order to satisfy the selectional properties of [VP seems] and T's EPP feature.

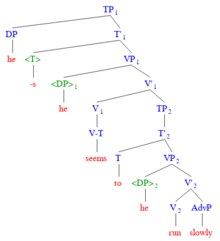

The following surface tree is expected, which follows the word order of the sentence provided:

In the surface representation, we see that DP movement is motivated by Locality of selection, movement is marked by brackets <>, (or at times arrows following the movement). The movement leaves behind a trace of the DP which still satisfies selection, however, the selection is now a non-local dependency.

Raising to Object

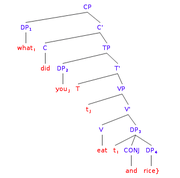

Wh-Movement

In wh-movement in English, an interrogative sentence is formed by moving the wh-word (determiner phrase, preposition phrase, or adverb phrase) to the specifier position of the complementizer phrase. This results in the movement of the wh-phrase into the initial position of the clause.[1] This is seen in English word order of questions, which show Wh components as sentence initial, though in the underlying structure, this is not so.

The wh-phrase must also contain a question word, due to the fact that it needs to qualify as meeting the +q feature requirements. The +q feature of the complementizer (+q= question feature) results in an EPP:XP+q feature: This forces an XP to the specifier position of CP. The +q feature also attracts the bound morpheme in the tense position to move to the head complementizer position; leading to do-support.[1]:260–262

Wh-Movement Violations

There are seven types of violations that can occur for wh-movement. These constraints predict the environments in which movement generates an ungrammatical sentence: Movement does not occur locally.

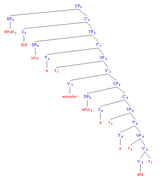

Wh-island constraint

| The Wh-island Constraint |

|---|

| If CP has the feature +q, movement of a wh-phrase to a position outside of the clause cannot occur.[1]:271 |

This definition tells us that if the specifier position of CP is occupied or if a C is occupied by a +q word, movement of a wh-phrase out of the CP cannot occur.[1]:271 In other words, a CP that has a wh-phrase in its [spec, CP] that is filled with another wh-phrase that is not the one that was extracted, but from higher in the tree. The movement of the wh-phrase is being obstructed by another wh-phrase.[1]

(6) a. [DP Who]i do you wonder [DP e]i bought what?

b. *[DP What]i do you wonder who bought [DP e]i? |

.png)

.png)

Example (6b) illustrates the wh-island constraint. The embedded clause contains a complementizer with the feature +q. This causes the DP "who" to move to the specifier position of that complementizer phrase. Movement of the complement DP "what" cannot occur since the specifier position of CP is filled. Therefore, movement of the wh-word "what" generates an ungrammatical sentence, while movement of the wh-word "who" is allowed (specifier position of the embedded CP is not occupied).

Adjunct island condition

| Adjunct Island Condition |

|---|

| If an adjunct contains a CP, movement of an element inside the CP to a position outside of the adjunct is not allowed.[1]:273 |

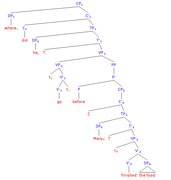

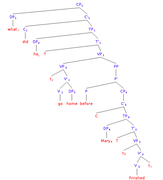

(7) a. [PP Where]i did he go [PP e]i before they finished the food?

b. *[DP What]i did he go home before Mary finished [DP e]i? |

Where did he go before they finished the food?

Where did he go before they finished the food? *What did he go home before Mary finished?

*What did he go home before Mary finished?

Example (7b) demonstrates the adjunct island condition. We can see that the wh-word, "what", occurs within the complementizer phrase that appears in the adjunct. Therefore, movement of the DP out of the adjunct will generate an ungrammatical sentence. Example (7a) is grammatical because the trace of the PP (prepositional phrase) "where" is not within the adjunct, therefore, movement is allowed. This demonstrates the prohibition of extraction from inside an adjunct and the condition that states that no element in a CP inside an adjunct may move out of this adjunct.

Sentential subject constraint

| The Sentential Subject Constraint |

|---|

| Movement of an element that appears within the CP subject cannot occur.[1]:273 |

A sentential subject is a subject that is a clause, not the subject of a sentence. Therefore, a clause that is a subject is called a sentential subject. The Sentential Subject Constraint is violated when an element moves out of a CP that is in the subject position.

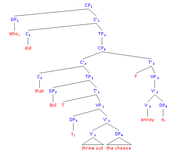

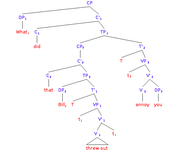

(8) a. [DP Who]i did that Bill threw out the cheese annoy [DP e]i?

b. *[DP What]i did that Bill threw out [DP e]i annoy you? |

Who did that Bill threw out the cheese annoy?

Who did that Bill threw out the cheese annoy? *What did that Bill threw out annoy you?

*What did that Bill threw out annoy you?

Example (8b) displays the sentential subject condition. The subject of the verb in this sentence is a complementizer clause. The DP "what" that appears within the CP subject moves to the specifier position of the main clause. The sentential subject constraint predicts that this wh-movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence since the trace was within the CP subject. Example (8a) is grammatical because the DP "who" does not have a trace within the CP subject, therefore, allowing movement to occur.

Coordinate structure constraint

| The Coordinate Structure Constraint |

|---|

| An element within a conjunct cannot undergo movement out of the conjunct.[1]:278 |

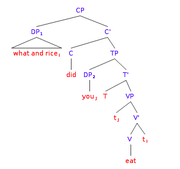

(9) a. [DP What and [rice]i did you eat [DP e]i?

b. *[DP What]i did you eat [DP ei and [rice]]?[1]:267 |

What and rice did you eat?

What and rice did you eat? *What did you eat and rice?

*What did you eat and rice?

Example (9a) is grammatical since the DP complement is moving as a whole to the specifier position of the matrix clause; nothing is extracted from the larger DP. Example (9b) is an example of the coordinate structure constraint. The DP "what" originally occurs within the DP conjunct, therefore, this constraint predicts that an ungrammatical sentence will result due to the extraction of an element within the conjunct.[1]:278

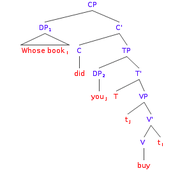

Complex NP constraint

| The Complex Noun Phrase Constraint |

|---|

| Extraction of an element that is a complement or adjunct of a NP is not allowed.[1]:274 |

(9) a. [DP Whose book]i did you buy [DP e]i?

b. *[D Whose]i did you buy [D e]i book? |

Whose book did you buy?

Whose book did you buy? *Whose did you buy book?

*Whose did you buy book?

Example (8a) is a grammatical because the DP complement of the verb moves as a whole to the specifier position of the main clause. Example (8b) displays the complex noun phrase constraint. The NP complement D, "whose", is extracted and moved to the specifier position of the main clause. The complex noun phrase constraint predicts that this wh-movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence since extraction of an element within the complex NP is not allowed.

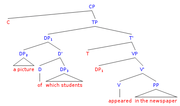

Subject condition

| The Subject Condition |

|---|

| Movement of a DP out of the subject DP of the verb is not allowed.[1]:277 |

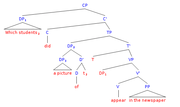

(10) a. A picture of which students appeared in the newspapers?

b. *[DP Which students]i did [DP a picture of [DP e]i] appear in the newspaper?[1]:277 |

A picture of which students appeared in the newspapers?

A picture of which students appeared in the newspapers? *Which students did a picture of appear in the newspapers?

*Which students did a picture of appear in the newspapers?

Example (10a) does not display any wh-movement. Therefore, the sentence is grammatical since nothing is extracted from the subject DP. Example (10b) contains wh-movement of a DP that is within the subject DP. The subject condition tells us that this type of movement is not allowed and the sentence will be ungrammatical.[1]:277

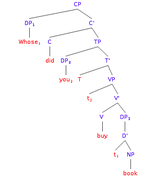

Left branch constraint

| The Left Branch Constraint |

|---|

| Extraction of a DP subject within a larger DP cannot occur.[1]:278 |

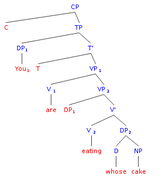

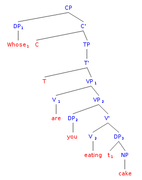

(11) a. You are eating [DP [DP whose] cake].

b. *[DP Whose]i are you eating [DP [DP ei] cake]?[1]:278 |

You are eating whose cake.

You are eating whose cake. *Whose are you eating cake?

*Whose are you eating cake?

In example (11a), there is no wh-movement, therefore the left branch constraint does not apply and this sentence is grammatical. In example (11b), the DP "whose" is extracted from the larger DP "whose cake." This extraction under the left branch constraint is not allowed, therefore, the sentence is predicted to be ungrammatical. This sentence can be made grammatical by moving the larger DP as a unit to the specifier position of CP.[1]:278

(12) c. [DP Whose cake]i are you eating [DP ei]? [1]:278 |

In example (12c), the whole subject DP structure undergoes wh-movement, which results in a grammatical sentence. This suggests that pied-piping can be used to reverse the effects of the violations or extraction constraints.[1]:278

(13) *[DP What]i did you wonder who ate ei? [1]:271 |

*What did you wonder who ate?

*What did you wonder who ate?

Example (13) is an example of a wh-island violation. There are two TP bounding nodes that appear between the DP "what" and its trace. The subjacency condition postulates that wh-movement cannot undergo when the elements are spread too far apart.[1] When two positions are separated by only one bounding node, or no bounding node at all, they are considered subjacent.[1] Therefore, according to the subjacency condition, movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence.[1]:271

See also

- Projection Principle

- Wh-movement

- Selection

- Binding Theory

- Subjacency

- X-bar Theory

- PRO

- Control Theory

References

- Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-4051-0017-5.

- Dominique., Sportiche (2013-09-23). An introduction to syntactic analysis and theory. Koopman, Hilda Judith., Stabler, Edward P. Hoboken. ISBN 9781118470480. OCLC 861536792.

- Boeckx, Cedric (2008). Bare Syntax. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953424-1.

- Sportiche, Dominique. (2013-09-30). An introduction to syntactic analysis and theory. Koopman, Hilda Judith,, Stabler, Edward P. Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 9781118470473. OCLC 842337755.

- Koster, Jan (1981). Locality Principles in Syntax. USA: Foris Publications. p. 178. ISBN 90-70176-06-8.

- Citko, Barbara (October 2011). "Small Clauses: Small Clauses". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (10): 748–763. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x.

- The Cambridge Handbook of Generative Syntax. Dikken, Marcel den, 1965-. Cambridge. 2014-05-14. ISBN 9781107341210. OCLC 854970711.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Haegeman, Liliane; Guéron, Jacqueline (1999). English Grammar: A Generative Perspective. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-631-18839-8.

- Culicover, Peter W. (1984). Locality in linguistic theory. Wilkins, Wendy K. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press. ISBN 0121992802. OCLC 9557971.