Littlemore Priory scandals

The Littlemore Priory scandals took place between 1517 and 1518. They involved accusations of sexual immorality and sometimes brutal violence among the nuns and the prioress of Littlemore Priory. The Oxfordshire Benedictine priory, which was very small and poor, had a history of troubled relations with its bishop. The scandal that came to light in 1517, however, became enough of a cause célèbre to contribute to the priory's eventual suppression in 1525. Katherine Wells, the prioress of Littlemore at that time, ran the priory with strict and often violent discipline. She was accused of regularly putting nuns in the stocks for extended periods, as well as physically assaulting them. She also had a baby by the priory's chaplain and had pawned the priory's jewels to pay for the child's upbringing. She entertained men in her parlour, even after the bishop had been made aware of the accusations, which involved heavy drinking. At least one other nun also had a child. On one occasion a number of the nuns broke out of the priory through a window and escaped into the surrounding villages for some weeks.[note 1]

The Bishop of Lincoln William Atwater[note 2] launched an investigation into the rumours of the nuns' irregular lifestyle. Trouble continued, however, and in a subsequent inquiry the bishop heard complaints from both the prioress and the nuns, who made accusations against each other. Wells was summoned to the bishop's court in Lincoln to face charges of corruption and incontinence which eventually led to her being dismissed from office. The end of the affair is unknown, as records have not survived. Historians consider it likely it was behaviour such as was found at Littlemore that encouraged Cardinal Wolsey's suppression of it, and a number of houses, in an attempt to improve the image of the church in England during the early 1520s. Wells, still acting prioress at its closure, received a life pension; the house became a farmstead and was gradually pulled down. One original building remained in the 21st century.

Background

William Alnwick's Records of Visitation, 1436–49

The Benedictine priory at Littlemore was founded in the 12th century by Robert de Sandford in the latter years of the reign of King Stephen.[5] Always a small house,[6] from around 1245[note 3] the priory's history is obscure, going unmentioned in both episcopal and government records. By the later Middle Ages, it was reported that the seven nuns of Littlemore were not living according to their rule. In 1445 the priory was visited by agents of William Alnwick, Bishop of Lincoln. Following their inspection, they reported the nuns failed to fast and ate meat every day. Furthermore, the prioress, Alice Wakeley, regularly received a Cistercian monk and a lay clerk in her rooms to indulge in drinking sessions.[7] There was much local gossip, and it appears to have been common knowledge that the nuns shared beds, apparently because the main dormer was structurally unsafe.[8] The bishop instructed the nuns were to use separate beds,[note 4] and that no lay persons, "especially scholars of Oxford",[7] were to be allowed admittance to the priory.[note 5] By the early years of the 16th century, the congregation had been reduced to a prioress and five nuns;[7] three of these, Elizabeth, Joan and Juliana,[13] were sisters surnamed Wynter.[14]

Atwater investigates, 1517

On 17 June 1517 Littlemore Priory was visited by Dr Edmund Horde, a commissary of Bishop William Atwater of Lincoln,[15][16][note 6] accompanied by the episcopal chancellor, Richard Roston.[19] The reasons for his visit are unknown, although Eileen Power suggests that around this time, Atwater "had awakened to the moral condition of Littlemore".[20] Horde's subsequent comperta, which were presented as findings of fact and were effectively accusations, were comprehensive. Firstly, he suggested the nuns had lied to him on their prioress's orders from the moment he arrived. They had told him all was well,[21]"omnia bene",[22] within Littlemore; he discovered this was not the case.[21] Investigators such as Horde were expected to be thorough, "examining each member of the house, going into the minutest details, and taking great pains to arrive at the truth".[23][note 7]

Horde reported the prioress, Katherine Wells,[note 8] had had an illegitimate daughter by Richard Hewes, a chaplain[26] from Kent, who was probably responsible for the priory's sacraments.[7] Thomson suggests this had clearly happened some years earlier, but had been either "concealed or deliberately overlooked by the authorities".[27] The nuns said Hewes still visited two or three times a year and was due again in early August.[16] While he was there, Hewes and Wells lived as a couple, and their child dwelt among the nuns.[28] Horde wrote that Wells, intending her daughter to make a good marriage, had stolen Littlemore's "pannes, pottes, candilsticks, basynes, shetts, pellous [and] federe bedds" and other furniture from the common store for the girl's dowry.[7][16] According to the bishop's records, although the nuns pleaded with Wells to give Hewes up, "she had answered that she would not do so for anybody, for she loved him and would love him".[16] Clandestine sexual relationships were not the sole purview of the prioress; at least one other nun, probably Juliana Wynter,[29][14] had also had a child by John Wikesley,[30] a married Oxford scholar,[29] two years previously.[29] For their part, the nuns complained to Horde that Wells was a brutal disciplinarian; when they tried to broach the subject with her, she would have them put in the stocks.[31] The historian Valerie G. Spears has suggested Wells was obsessed with discipline; on the one hand this was "self-defeating", and on the other encouraged by the nuns' servility.[32]

The nuns also complained that no effort had been put into maintaining the priory or its buildings, and they pointed out damaged and leaking roofs and walls.[28] Essential outbuildings had been leased by Wells to the priory's secular neighbours, and she had kept the rents herself.[16] They also protested their decrepit clothing, poor and insufficient food and bad ale.[33] Horde discovered the bulk of the priory's foundation wealth, including its jewellery, had been pawned[31][note 9] or spent on the prioress's "evil life". At the same time, the nuns lacked basic necessities, including food and clothing, and could not purchase anything for themselves as the prioress regularly confiscated their stipends.[7] They said Wells sent these funds outside the priory to be distributed among her relatives.[33] They complained her general behaviour also set a bad example: rather than spend her days in contemplation or the administration of the house, she would roam the surrounding countryside with no companion other than a young child from a nearby village.[16] Horde heard that such a state of affairs was damaging recruitment: women who may have been thinking of taking the veil at Littlemore saw the conditions they would be expected to live under and went elsewhere instead.[7] It was claimed on at least one occasion a potential recruit had not only walked out immediately, but had proceeded to advertise the poor state of the priory throughout Oxford.[30][note 10] Potential benefactors were also being deterred.[35] The church historian Philip Hughes suggests that nuns demanded that Horde remedy their complaints. They had requested permission to leave the house for another if he could not,[28] possibly out of fear of Wells's expected retribution after he had left.[30]

Visit of the bishop

|

Littlemore's circumstances appear not to have changed over the next year.[30] On 2 September 1518,[36] Atwater visited Littlemore personally.[30][36] Although he had "to bring about some reformation" at Littlemore, the bishop was disappointed.[7] On this visit, Wells complained to him that nuns refused to obey her.[26] She reported that Elizabeth Wynter[14] "played and romped"[7] in the cloister with men from Oxford,[note 11] and, aided by her sisters, had defied the prioress's attempts to correct her. For example, the prioress explained she had put Elizabeth in the parlour stocks only for three of her colleagues, the two other Wynter sisters[14] and one Anna Wilye,[13] to break the door open and release her. Wells must have locked Wynter in, as her rescuers broke the lock as well. The four of them then set fire to the stocks and barricaded the door against Wells.[29] She summoned aid from neighbours and servants, but before help could arrive, the nuns had broken the window and escaped into a nearby village. There they hid with a sympathetic neighbour, "one Inglyshe",[30] for some weeks,[7][29] and were apostastised as a result.[13] They had also been persistently disrespectful during the mass, playing games, chattering and laughing loudly throughout,[29] acting with generally wanton behaviour,[30] "even at the elevation", despite their supposed obedience to attentiveness and decorum.[38][note 12] Wells complained that even though it had been two years since Juliana Wynter had given birth, she had learned nothing of the errors of her ways and still eagerly sought the company of men.[29]

The nuns, for their part, complained that the prioress had sold off all their wood and that Hewes had stayed with the prioress for over five months.[30][note 13] Worse, after the previous visitation, she had ruthlessly punished those who had spoken the truth about Littlemore to Edmund Horde. Anne Wilye had spent a month in the stocks, and Elizabeth Wynter had been physically beaten in the chapter house and the cloister.[29] The bishop was told, when Wynter eventually returned from the village with her absconding colleagues,[14] how Wells had hit Elizabeth "on the head with fists and feet, correcting her in an immoderate way",[7] and repeatedly stamped on her.[30] The nuns also claimed that, despite Wells's promises to Atwell, Hewes had continued to visit the prioress since the Horde's visitation.[7] Logan suggests it may have been Elizabeth who had reported Wells to Horde during the 1517 visit and that this was the prioress's revenge.[14] One nun, Juliana Bechamp, who seems to have remained uninvolved in the various troubles, told the bishop that she was "ashamed to [be] here [under] the evil ruele [of] my ladye".[33] The scandals besetting Littlemore Priory were by then very much public knowledge, and both prioress and nuns had their supporters in the City of Oxford.[41] The historian Peter Marshall has described them as "eye-catching",[21] and Spears suggests they provided "the sensationalist media of the day with profitable copy".[32]

Confession of the prioress

A few months following his visit, Bishop Atwater summoned Katherine Wells to his court in Lincoln. She faced numerous charges[42] including incontinence[25] and deliberate immorality.[39][note 14] Bowker says the proceedings lasted several days during which she was interrogated by both the bishop and his officials including Dr Peter Potkyn, the episcopal canonist at counsel.[42][44]

At first Wells denied the accusations, but the weight of Horde's evidence forced a confession. She revealed her daughter had died in 1513, and that she had given Richard Hewes some of the priory's silver plate since then, including a silver goblet worth five marks.[16][note 15] She claimed to have maintained the same lifestyle for the previous eight years, but that no one had enquired into Littlemore's affairs in all that time. Rather, she said, the priory had had no contact with officialdom except for one occasion when she had received some ecclesiastical injunctions a few years before.[7] On the final day of the hearing, Atwater gathered the evidence and pronounced his judgment.[42]

As punishment, Wells was dismissed from her office, although she was permitted to carry out the day-to-day duties the house required until a replacement had been organised. This was on the strict condition that she would do nothing apart from this without Horde's personal authorisation,[7][note 16] especially in regard to matters of internal discipline.[42] The historian J. A. F. Thomson has described the situation, specifically the bishop's dismissal of Wells in the knowledge that she would have to be allowed to continue, as demonstrating the "inadequacy of visitations as a means of enforcing discipline".[26] The medievalist Eileen Power agrees that "it shows how inadequate, in some cases, was the episcopal machinery for control and reform" of such institutions as Littlemore.[41] She places the blame for Littlemore's condition squarely on Wells's shoulders, with her "habitual incontinence [and] persecution of her nuns",[47] whom she describes as "a particularly bad prioress".[31] Power notes that such a situation was far more likely to arise in small, poor houses,[48] which medievalist F. D. Logan suggests were often already "struggling for survival",[49] than in houses with independent wealth.[48] Spears agrees with Power on Wells's irresponsibility, suggesting that if her nuns subsequently behaved poorly, "it would be surprising"[39] if this was not the result of observing, learning and copying her behaviour and approach.[39] Spears notes that, as Wells utilised "erratic and aggressive" discipline, so the nuns seem to have behaved reciprocally towards her.[32]

Aftermath

Historians do not know what, if any, action Atwater took regarding Littlemore following his visit, as subsequent records no longer exist and neither Littlemore or its inhabitants receives further mention in the bishop's Registrum.[16] Nor do we know what, if any, measures Horde took while the priory was in his care.[50] By 1525, the King's chief minister, Cardinal Wolsey, was in the process of founding his new school of humanist education Cardinal College, Oxford. He needed funds for the building.[51] To raise what he needed he requested and acquired a papal bull authorising him to suppress several decayed monasteries of his choice.[52] In Wolsey's eyes, this also had the benefit of helping repair the church's reputation in England, which decadent houses and their inhabitants had helped give it. Littlemore was one of the priories he chose for dissolution.[note 17] Power argued the condition of the house and its reputation for scandal, on top of Wolsey's wish to expand the University, justified this decision.[41] That Littlemore had proved itself intractable, unable to reform itself or to allow itself to be reformed, probably made it a likely candidate for dissolution, which Margaret Bowker says was "the only way to prevent its disobedience spreading".[35] Hughes has described Littlemore as being, to Wolsey, simply a house "that would never be missed".[29]

At the time of its closure, Littlemore Priory was worth around £32 per annum.[7][note 18][note 21] Over the next few years, its lands and revenues were given over to Wolsey's new college.[26] The inhabitants received no further punishment. Indeed, as the last prioress, Katherine Wells was given an annual pension of £6 13s 4d,[26][note 22] and those nuns who had been apostatised on account of their misbehaviour were absolved.[56] When Wolsey fell from power in 1529, Littlemore Priory, along with the rest of his wealth and estates, escheated to the crown.[57][51]

Eileen Power has described Littlemore's conditions in the early 16th century as making it "one of the worst nunneries for which records survive".[31] She suggests it illustrates that although Thomas Cromwell exaggerated the case, there was clearly some basis in recent history for the allegations of decadent institutions and scurrilous behaviour that he used as justification for the wholesale dissolution of the monasteries of 1536–1539.[41] As for Bishop Atwater, Bowker has suggested that, although he made conscientious efforts to reform recalcitrant houses within his jurisdiction, Littlemore Priory is merely one example of his failure to come to grips with the problem throughout his career. She does argue, though, that Atwater's efforts in this direction anticipated, in a small way, Martin Luther's attempted reforms of the church.[58]

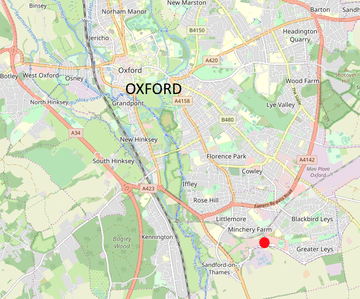

The few buildings that made up the priory were soon turned into farmsteads.[1] Only the east range of Littlemore's cloister survived into the 21st century and it is now Grade II* listed.[59] Described by Nikolaus Pevsner's Buildings of England as "a rectangular building with a small gabled block",[6] this had originally housed the nuns' dormitory on the first floor and the chapter house and prioress's parlour on the ground.[6] It was converted into a pub in the late 20th century, although this was closed by 2015. The pub's closure presented the opportunity for an archaeological survey of the site. A number of "very unusual burials" were discovered within the priory's precincts, including one who had likely been a prioress, a body which had received a blunt-force trauma to its head, and a woman who was buried with a baby.[60]

Notes

- Logan has argued that, for the purposes of describing these nuns, the terms "runaway", "renegade" and "wayward" are interchangeable for the modern audience, but he argues a more accurate description of how contemporaries defined absconders was as apostates: "The term used by popes and bishops in fashioning laws against them, by religious superiors contending with them in practice, by the rules, constitutions and customs of orders is the word 'apostates'. Apostata was the word used consistently by contemporaries to describe the religious who climbed over the wall literally or figuratively".[2]

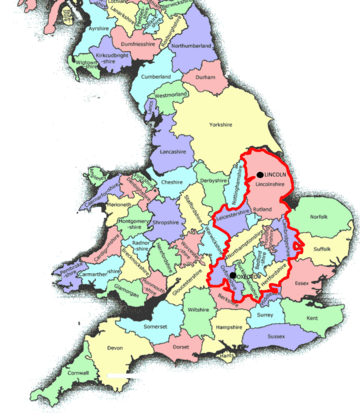

- Until 1541, the diocese of Lincoln was the largest in England, and covered, as well as Lincolnshire itself, the counties of Bedford, Buckingham, Huntingdon, Leicester, Northampton, Oxford and Rutland.[3]

- When the priory received a papal bull encouraging local men to help the nuns rebuild their decrepit dormitory in return for indulgences.[7]

- The medievalist Sarah Salih has commented upon the bishop's instructions. Although in this period "it is very rare to find any anxiety about same-sex activity in nunneries",[9] Atwater may have been concerned that this was taking place at Littlemore since he instructs "that fro hens for the ylke one of yowe lyg separatly in one bed by hire selfe". On the other hand, Salih notes that "the Benedictine Rule allowed beds to be shared when space was short, the nuns openly confess they share their beds, explaining that their dormer is in ruins, and the rubric to the Littlemore visitation contains none of the references to modesty or shamefastness which usually appear when sexual transgression is at issue".[9] Logan has argued that "the stereotype of the monk running off with the nun is simply not sustained by the evidence that exists".[10] Regarding the medieval nuns' sleeping arrangements the archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist has commented that, while some houses such as Burnham Abbey favoured a communal dormer, Littlemore's was partitioned in discrete cubicles, configured as "two rows of chambers (approximately 2.4 by 3 m each) lit by small windows"[11]

- Littlemore was not alone in earning Alnwick's ire: during his episcopacy (1436–49) he found cause to reprimand the prioresses of Ankerwyke, Catesby, Gracedieu, Harrold, Heynings, Langley, Legbourne, Markyate and Stamford priories.[12]

- A graduate and fellow of All Soul's College, at the time of his visitation to Littlemore, Horde held a number of benefices in Oxfordshire. He surrendered these in 1520 to allow him to join the Carthusian order, and was appointed prior of Hinton in 1529.[17] The ecclesiastical historian Diarmaid MacCulloch says Horde was "much respected" in his lifetime, and he and his house stayed loyal to the king during the Dissolution.[18]

- R. S. Arrowsmith commented this was not "always easy"; the abbot or prioress "could make things very unpleasant for those who revealed the true state of the house". He illustrates this with the cases of the 1514 visitation to Walsingham Priory, where the prior reminded the monks he would still be in charge when their bishop had left. The same year, the nuns of Flixton Priory stated they could not tell the truth during a visitation because of their lady's cruelty. Likewise, in 1440, the prioress of Legbourne had forbidden her nuns to report anything ("well knowing that her own conduct would not bear scrutiny", says Arrowsmith).[24]

- Or "Wellys".[25]

- Power notes that "the charge of pawning or selling jewels for their own purposes was often made against prioresses whose conduct in other ways was bad". Apart from Katherine Wells in 1517, this charge was also faced by Eleanor of Arden Priory in 1396, Juliana of Bromhall Priory in 1404 and Agnes Tawke of Easebourne Priory in 1478.[34]

- Thomson suggests that, notwithstanding the reputations of places such as Littlemore, this particular incident indicates "some individuals still had an idealistic view of the regular life, which could be shattered by a discrepancy between theory and practice".[27]

- The word used in his report is luctando, which latinist Danuta Shanzer says is usually used in the context of "sexual exhaustion, whether masturbation, nocturnal emissions or sexual intercourse";[37] Philip Hughes translates Wynter's activity as wrestling: Neque voluit corrigi per priorissam licet deliquerit ludendo et luctando cum pueris in claustro.[29]

- The medievalist Valerie Spear has suggested this may be the only recorded case of such "studied irreverence" in a 16th-century English priory.[39]

- He had arrived sometime around Easter, which had fallen on 4 April that year.[40]

- Specific charges included sleeping with Hewes at Candlemas that year, impeding Horde's investigation by threatening reprisals on nuns who told him the truth and neglecting the repair and maintenance of the fabric of the house.[43]

- A medieval English mark was an accounting unit equivalent to two-thirds of a pound.[45]

- The appointment of a mentor to a nunnery had been common practice 200 years earlier, but by the 16th century had fallen out of fashion to the extent of being almost unheard of.[46]

- It was not the only one; in all, Wolsey suppressed 28 houses, all of them priories except two, which were abbeys, and of which four including Littlemore were nunneries.[53] Some were dissolved for similar reasons. "Littlemore was not the only house which suffered suppression under the shadow of scandal", wrote Thomson, and "in 1522 an inquisition was held into the lands of Broomhall Priory, Berkshire, where the prioress had resigned in September 1521 and left with two other nuns in December. The Inquisition gave no explanation for the prioress's departure, but in 1524 Clement VII issued a bull suppressing the house, and also that of Higham, Kent, on account of the demerits of the nuns".[26] Other priories suppressed by Wolsey at this time were those of Wix in Essex, also in 1525; Farewell in Staffordshire, in 1527;[54] and St Mary de Pré, St Albans the following year.[55] Farewell's income went to the diocese; the others' went to Wolsey's new Oxford college.[54]

- £23,400 in 2018.

- £8,800 in 2018.

- £15,600 in 2018.

- According to the Victoria County History, this was divided between "£12[note 19] in spiritualities (no doubt the church of Sandford), and £21 6s 6d[note 20] in temporalities, some part of this being from houses in Oxford".[7]

- £4,900 in 2018.

References

- Pantin 1970, p. 19.

- Logan 1997, p. 2.

- King 1862, p. 326.

- Thompson 1918, p. 218.

- VCH 1957, p. 169.

- Pevsner & Sherwood 1974, p. 689.

- VCH 1907, pp. 75–77.

- Williams 2006, p. 3.

- Salih 2001, p. 150.

- Logan 1997, p. 7.

- Gilchrist 1994, p. 123.

- Spear 2005, p. 131.

- Logan 1996, p. 261.

- Logan 1996, p. 81.

- Power 1922, p. 492.

- Thompson 1940, p. lxxvi.

- Connolly 2019, p. 156.

- MacCulloch 2018, p. cxiii.

- Thompson 1940, p. 144.

- Power 1922, pp. 491–492.

- Marshall 2017, p. 53.

- Fraser 1987, p. 45.

- Arrowsmith 1923, pp. 143–144.

- Arrowsmith 1923, p. 144.

- Smith 2008, p. 664.

- Thomson 1993, p. 231.

- Thomson 1993, p. 230.

- Hughes 1951, p. 57.

- Hughes 1951, p. 58.

- Thompson 1940, p. lxxvii.

- Power 1922, p. 595.

- Spear 2005, p. 153.

- Tucker 2017, p. 23.

- Power 1922, p. 211.

- Bowker 1981, p. 28.

- Bowker 1967, p. xxix.

- Shanzer 2006, p. 193 n.91.

- Kerr 2009, p. 153.

- Spear 2005, p. 122.

- Cheney 1995, p. 110.

- Power 1922, p. 596.

- Bowker 1967, p. ix.

- Bowker 1967, pp. 46–47.

- Selden Society 1999, p. 687.

- Harding 2002, p. xiv.

- Thompson 1940, pp. lxxvii–lxxviii.

- Power 1922, p. 491.

- Power 1922, p. 452.

- Logan 1996, p. 69.

- Thompson 1940, p. lxxviii.

- Elton 1991, p. 94.

- Everett 2015, pp. 30–31.

- Cook 1965, p. 262.

- Power 1922, p. 604.

- Spear 2005, p. 170.

- Logan 1996, p. 84.

- VCH 1957, p. 270.

- Bowker 2004.

- Historic England. "Minchery Farmhouse (Grade II*) (1047672)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- BBC 2015.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, R. S. (1923). The Prelude to the Reformation: A Study of English Church Life from the Age of Wycliffe to the Breach with Rome. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 276858035.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alnwick, W. (1918). Thompson, A. H. (ed.). Visitations of Religious Houses in the Diocese of Lincoln: Records of Visitation held by William Alnwick, Bishop of Lincoln, A.D. 1436 to A.D. 1449. XIV. Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society. OCLC 655742236.

- Atwater, W. (1940). Thompson, A. H. (ed.). Visitations in the Diocese of Lincoln 1517–1531. Vol. 1 Visitations of Rural Deaneries by William Atwater, Bishop of Lincoln, and his Commissaries 1517–1520. XXXIII. Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society. OCLC 560563565.

- BBC (12 May 2015). "Oxford archaeologists find 92 skeletons at medieval church site". BBC News. OCLC 33057671. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowker, M., ed. (1967). An Episcopal Court Book for the Diocese of Lincoln: 1514–1520. Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society. OCLC 865886643.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowker, M. (1981). The Henrician Reformation: The Diocese of Lincoln Under John Longland 1521–1547. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52123-639-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowker, M. (2004). "Atwater, William (d. 1521), Bishop of Lincoln". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/879. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (subscription required)

- Caryll, J. (1999). Reports of Cases by John Caryll. London: Selden Society. ISBN 978-0-85423-140-9.

- Cheney, C. R. (1995). A Handbook of Dates: For Students of English History (repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52155-151-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connolly, M. (2019). Sixteenth-Century Readers, Fifteenth-Century Books: Continuities of Reading in the English Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10842-677-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, G. H. (1965). Letters to Cromwell on the Suppression of the Monasteries. London: J. Baker. OCLC 936470729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elton, G. R. (1991). Reform and Reformation: England 1509–1558. A New History of England. II (repr. ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-71315-953-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Everett, M. (2015). The Rise of Thomas Cromwell: Power and Politics in the Reign of Henry VIII, 1485–1534. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3002-1308-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fraser, F. (1987). The English Gentlewoman. London: Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 978-0-71261-768-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilchrist, R. (1994). Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41508-903-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harding, V. (2002). The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500–1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52181-126-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, P. (1951). The Reformation in England: The King's Proceedings. I. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 908867941.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kerr, J. (2009). Life in the Medieval Cloister. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-161-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, R. J. (1862). Handbook to the Cathedrals of England: Eastern Division. Oxford, Peterborough, Norwich, Ely, Lincoln. London: John Murray. OCLC 886346587.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Logan, F. D. (1996). Runaway Religious in Medieval England, c. 1240–1540. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52147-502-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Logan, F. D. (1997). "Renegade Religious in Late Medieval England". In Devlin, J.; Fanning, R. (eds.). Religion and Rebellion: Papers Read Before the 22nd Irish Conference of Historians Held at University College Dublin. Historical Studies. XX. Dublin: Dublin University Press. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-90062-103-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacCulloch, D. (2018). Thomas Cromwell: A Life. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14196-766-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, P. (2017). Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30022-633-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pantin, W. A. (1970). "Minchery Farm". Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. XXXV: 19–26. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pevsner, N.; Sherwood, J. (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England (repr. 2002 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Power, E. (1922). Medieval English Nunneries: C.1275 to 1535. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 458113609.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salih, S. (2001). Versions of Virginity in Late Medieval England. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-622-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shanzer, D. (2006). "Latin Literature, Christianity and Obscenity in the Later Roman West". In McDonald, M. (ed.). Medieval Obscenities. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 179–202. ISBN 978-1-90315-350-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, D. M. (2008). The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales: 1377–1540. III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52186-508-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spear, V. G. (2005). Leadership in Medieval English Nunneries. Studies in the History of Medieval Religion XXIV. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-150-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, J. A. F. (1993). The Early Tudor Church and Society 1485–1529. Harlow: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-58206-377-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, R. A. (2017). Katie Luther, First Lady of the Reformation: The Unconventional Life of Katharina von Bora. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-31053-215-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- VCH (1907). A History of the County of Oxford. II. London: Victoria County History. OCLC 321945.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- VCH (1957). A History of the County of Oxford. V. London: Victoria County History. OCLC 490851365.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, G. (2006). An Archaeological Evaluation at Minchery Farm, Oxford (Report). John Moore Heritage Services. pp. 1–38. doi:10.5284/1007896. OASIS johnmoor1-38382.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)