List of lakes in Minneapolis

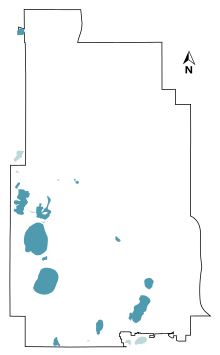

There are 13 lakes of at least five acres (two hectares)[lower-alpha 1] within the borders of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Of these, Bde Maka Ska is the largest and deepest, covering 421 acres (170.37 ha) with a maximum depth of 89.9 feet (27.4 m). Lake Hiawatha, through which Minnehaha Creek flows, has a watershed of 115,840 acres (468.79 km2), two orders of magnitude larger than the next largest watershed in the city.[2] Ryan Lake, in the city's north, sits partially in Minneapolis and partially in neighboring Robbinsdale.[3][4] Certain other bodies of water are counted on some lists of Minneapolitan lakes, though they may fall outside the city limits or cover fewer than five acres.

Many of Minneapolis's lakes formed in the depressions left by large blocks of ice after the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at the end of the last glacial period and now overlie sandy or loamy soils.[5][6] Before the appearance of white settlers, the Dakota harvested wild rice from the lakes.[7] In the early 1800s, the lakes' shorelines were marshy, deterring large-scale settlement and development by white residents though an experimental Dakota agricultural community, Ḣeyate Otuŋwe, was founded on the banks of Bde Maka Ska by Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa in 1829.[7][8] In the 1880s, landscape architect Horace Cleveland foresaw Minneapolis's growth and made a series of recommendations to the city's Board of Park Commissioners to acquire land along Minnehaha Creek, near Minnehaha Falls, and around several lakes in the southwest portion of the city in order to form a robust, interconnected park system that would aesthetically and morally benefit the city's residents. Board president Charles M. Loring heeded Cleveland's advice and bought the land, later developed into a robust system of parks by Theodore Wirth.[9] During this time, many of the lakes were reformed by the Board of Park Commissioners through draining, dredging, shoreline stabilization, and the construction of parkways around their perimeters.[5][8] Property in neighborhoods surrounding the lakes grew desirable, especially by the "Chain of Lakes", five lakes in the southwestern portion of the city (Maka Ska, Harriet, Isles, Cedar, and Brownie) that were joined by artificial channels.[8]

Various municipal symbols and icons reference the presence of the lakes in Minneapolitan life, from the sailboat in the city's logo to the ship's wheel on its flag to Minneapolis's nickname, the "City of Lakes".[10][11][12] Much of Minneapolis's lakeshore is public parkland, in contrast to other American cities where lakeside property tends to be privately controlled.[13] Since they were dredged, the lakes have drawn city residents for recreation and sport including swimming, sailing, yachting, canoeing, biking, jogging, and ice skating.[14] The 76-mile (122.3 km) Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway passes around many of Minneapolis's lakes.[9]

List of lakes

| Lake | Image | Area | Maximum depth | Watershed area | Coordinates | Notes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brownie Lake |  |

18 acres (0.07 km2) | 49.9 feet (15.2 m) | 369 acres (1.49 km2) | 44.9675428°N 93.3242747°W |

|

[2][8] |

| Cedar Lake |  |

170 acres (0.69 km2) | 50.9 feet (15.5 m) | 1,956 acres (7.92 km2) | 44.9600374°N 93.3209776°W |

|

[2][8][15] |

| Cemetery Lake | %2C_June_2016.jpg) |

11 acres (0.04 km2) | Unknown | Unknown | 44.9327725°N 93.3060642°W |

|

[16][17][18] |

| Diamond Lake |  |

41 acres (0.17 km2) | 6.9 feet (2.1 m) | 669 acres (2.71 km2) | 44.9006469°N 93.2692419°W | [2] | |

| Grass Lake |  |

27 acres (0.11 km2) | 4.9 feet (1.5 m) | 386 acres (1.56 km2) | 44.8927159°N 93.2982813°W | [2] | |

| Lake Harriet |  |

353 acres (1.43 km2) | 82.0 feet (25.0 m) | 1,139 acres (4.61 km2) | 44.9219536°N 93.3061669°W |

|

[2][8] |

| Lake Hiawatha |  |

54 acres (0.22 km2) | 23.0 feet (7.0 m) | 115,840 acres (468.79 km2) | 44.9211849°N 93.2360063°W |

|

[2][19] |

| Lake of the Isles |  |

103 acres (0.42 km2) | 30.8 feet (9.4 m) | 735 acres (2.97 km2) | 44.955087°N 93.3096144°W |

|

[2][8] |

| Loring Lake |  |

8 acres (0.03 km2) | 17.4 feet (5.3 m) | 24 acres (0.10 km2) | 44.9689373°N 93.2844032°W |

|

[2][16] |

| Bde Maka Ska |  |

421 acres (1.70 km2) | 89.9 feet (27.4 m) | 2,992 acres (12.11 km2) | 44.9418644°N 93.3117332°W |

|

[2][8][20] |

| Lake Nokomis |  |

204 acres (0.83 km2) | 33.1 feet (10.1 m) | 869 acres (3.52 km2) | 44.9086107°N 93.2420323°W |

|

[2][15] |

| Powderhorn Lake |  |

11 acres (0.04 km2) | 20.0 feet (6.1 m) | 286 acres (1.16 km2) | 44.9417498°N 93.2568019°W | [2] | |

| Ryan Lake |  |

18 acres (0.07 km2) | 35.1 feet (10.7 m) | 5,510 acres (22.30 km2) | 45.0410713°N 93.3221358°W | [2] | |

Other bodies of water

.jpg)

Some sources, including the City of Minneapolis's own geographic information system (GIS) dataset, list up to 22 lakes within the city.[16][21][22][23] The dataset lists three lakes that are not within the city's borders:[4][16]

- Mother Lake (48 acres [0.19 km2])

- Wirth Lake (39 acres [0.16 km2])[lower-alpha 2]

- Taft Lake (14 acres [0.06 km2])

The list includes some bodies of water smaller than five acres:[16]

- Birch Lake (3.2 acres [12,949.94 m2])

- Spring Lake (2.3 acres [9,307.77 m2])

- Lake Mead (1.8 acres [7,284.34 m2])

- Legion Lake (0.5 acres [2,023.43 m2])

The Minneapolis GIS dataset includes two of the channels between larger bodies of water as "lakes":[16]

- Cedar–Isles Channel (5.4 acres [21,853.02 m2])

- Maka Ska–Isles Channel (3.4 acres [13,759.31 m2])

Additionally, there are 46 ponds in Minneapolis.[16]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lakes of Minneapolis. |

- List of lakes in Minnesota

- List of shared-use paths in Minneapolis

Notes

- Moss et al. suggested that for a body of water to be considered a lake, it should cover at least two hectares (five acres).[1]

- Wirth Lake is a component of Theodore Wirth Regional Park, a Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board-managed property that is mostly located within the borders of Golden Valley.[24] The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board was established in 1883 by the Minnesota Legislature and is a distinct entity from the City of Minneapolis, with its own power to levy taxes and acquire land.[25]

References

- Moss, Brian; Johnes, Penny; Phillips, Geoffrey (May 1996). "The Monitoring of Ecological Quality and the Classification of Standing Waters in Temperate Regions: a Review and Proposal Based on a Worked Scheme for British Waters". Biological Reviews. 71 (2): 301–339. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1996.tb00750.x.

- Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board Environmental Stewardship (April 2016). "Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board 2014 Water Resources Report" (PDF). Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- Wilson, Craig (September 2003). "Ryan Lake Trail Concept Plan" (PDF). Center for Urban and Regional Studies. University of Minnesota. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Street Map (PDF) (Map). City of Minneapolis. June 30, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Myrbo, Amy; Murphy, Marylee; Stanley, Valerie (2011). "The Minneapolis Chain of Lakes by bicycle: Glacial history, human modifications, and paleolimnology of an urban natural environment". In Miller, James D.; Hudak, George J.; Wittkop, Chad; McLaughlin, Patrick I. (eds.). Archean to Anthropocene: Field Guides to the Geology of the Mid-Continent of North America. GSA Field Guides. 24. Boulder, CO: The Geological Society of America. pp. 425–437. doi:10.1130/2011.0024(20). ISBN 978-0-8137-0024-3.

- McBride, Mark S. (1976). Hydrology of lakes in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul Metropolitan Area: A summary of available data (PDF) (Report). Saint Paul, MN: U.S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division. doi:10.3133/wri7685. Water-Resources Investigations Report 76-85.

- Beane, Katherine (2012). "Bde Maka Ska / Lake Calhoun, Minneapolis". In Westerman, Gwen; White, Bruce (eds.). Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 104–107. ISBN 978-0-87351-869-7.

- Millett, Larry (2009). AIA Guide to the Minneapolis Lake District. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-87351-645-7.

- Adams, John S.; Vandrasek, Barbara J. (1993). Minneapolis–St. Paul: People, Place, and Public Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-8166-2236-8.

- Roper, Eric (March 18, 2015). "Revealed: The story behind Minneapolis' sailboat logo". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "Minneapolis City Flag". City of Minneapolis. June 7, 2016. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Hintz, Martin (2003). Minnesota Family Weekends. Black Earth, WI: Trails Books. p. 1. ISBN 1-931599-22-X.

- Cornell, Tricia (2016). Moon Minneapolis & St. Paul (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Avalon Travel. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-63121-272-7.

- Lanegran, David A.; Sandeen, Ernest R. (2004). The Lake District of Minneapolis: A History of the Calhoun–Isles Community. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 49–67. ISBN 0-8166-4422-5.

- Rhodes, James B. (March 1956). "The Fort Snelling Area in 1835: A Contemporary Map" (PDF). Minnesota History. 35 (1): 22–29. JSTOR 20175983.

- "Water". OpenData Minneapolis. City of Minneapolis. June 17, 2012. Archived from the original on June 21, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- "T. S. Roberts Bird Sanctuary Improvements Project" (PDF). Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. February 18, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Osteen, Mame (1992). Haven in the Heart of the City: The History of Lakewood Cemetery. Minneapolis: Lakewood Cemetery. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-9635227-0-1.

- Felien, Ed (November 7, 2017). "The future of Hiawatha Golf Course". Southside Pride. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Chanen, David (January 18, 2018). "The state officially changes Lake Calhoun to Bde Maka Ska". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- Long, Donna Tabbert (2001). Tastes of Minnesota: A Food Lover's Tour. Black Earth, WI: Trails Books. p. 129. ISBN 0-915024-95-0.

- Porges, Lawrence M., ed. (2014). The World's Best Cities: Celebrating 220 Great Destinations. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4262-1378-6.

- Kronick, Richard L. (May–June 2001). "Minneapolis: A City That Works". The Old-House Journal. pp. 93–96. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Millett, Larry (2007). AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: The Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-87351-540-5.

- Smith, David C. (2008). City of Parks: The Story of Minneapolis Parks. Minneapolis: The Foundation for Minneapolis Parks. pp. 20–24. ISBN 978-0-615-19535-3.