Linoleum

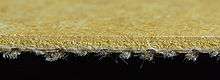

Linoleum, commonly abbreviated to lino, is a floor covering made from materials such as solidified linseed oil (linoxyn), pine resin, ground cork dust, sawdust, and mineral fillers such as calcium carbonate, most commonly on a burlap or canvas backing. Pigments are often added to the materials to create the desired colour finish.

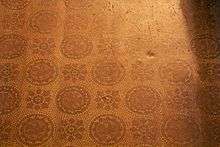

The finest linoleum floors, known as "inlaid", are extremely durable, and are made by joining and inlaying solid pieces of linoleum. Cheaper patterned linoleum comes in different grades or gauges, and are printed with thinner layers which are more prone to wear and tear. High-quality linoleum is flexible and thus can be used in buildings where a more rigid material (such as ceramic tile) would crack.

History

Linoleum was invented by Englishman Frederick Walton.[1] In 1855, Walton happened to notice the rubbery, flexible skin of solidified linseed oil (linoxyn) that had formed on a can of oil-based paint and thought that it might form a substitute for India rubber. Raw linseed oil oxidizes very slowly, but Walton accelerated the process by heating it with lead acetate and zinc sulfate. This made the oil form a resinous mass into which lengths of cheap cotton cloth were dipped until a thick coating formed. The coating was then scraped off and boiled with benzene or similar solvents to form a varnish. Walton initially planned to sell his varnish to the makers of water-repellent fabrics such as oilcloth, and patented the process in 1860. However, his method had problems: the cotton cloth soon fell apart, and it took months to produce enough of the linoxyn. Little interest was shown in Walton's varnish. In addition, his first factory burned down, and he suffered from persistent and painful rashes.

Walton soon came up with an easier way to transfer the oil to the cotton sheets, by hanging them vertically and sprinkling the oil from above, and he tried mixing the linoxyn with sawdust and cork dust to make it less tacky. In 1863 he applied for a further patent, which read: "For these purposes canvas or other suitable strong fabrics are coated over on their upper surfaces with a composition of oxidized oil, cork dust, and gum or resin ... such surfaces being afterward printed, embossed, or otherwise ornamented. The back or under surfaces of such fabrics are coated with a coating of such oxidized oils, or oxidized oils and gum or resin, and by preference without an admixture of cork."

At first Walton called his invention "Kampticon", which was deliberately close to Kamptulicon, the name of an existing floor covering, but he soon changed it to Linoleum, which he derived from the Latin words linum (flax) and oleum (oil). In 1864 he established the Linoleum Manufacturing Company Ltd., with a factory at Staines, near London. The new product did not prove immediately popular, mainly due to intense competition from the makers of Kamptulicon and oilcloth. The company operated at a loss for its first five years, until Walton began an intensive advertising campaign and opened two shops in London for the exclusive sale of Linoleum. Walton's friend Jerimiah Clarke designed the linoleum patterns, typically with a Grecian urn motif around the borders.

Other inventors began their own experiments after Walton took out his patent, and in 1871 William Parnacott took out a patent for a method of producing linoxyn by blowing hot air into a tank of linseed oil for several hours, then cooling the material in trays. Unlike Walton's process, which took weeks, Parnacott's method took only a day or two, although the quality of the linoxyn was not as good. Despite this, many manufacturers opted to use the less expensive Parnacott process.

Walton soon faced competition from other manufacturers, including a company which bought the rights to Parnacott's process, and launched its own floor covering, which it named Corticine, from the Latin cortex (bark or rind). Corticine was mainly made of cork dust and linoxyn without a cloth backing, and became popular because it was cheaper than linoleum.

By 1869 Walton's factory in Staines, England was exporting to Europe and the United States. In 1877, the Scottish town of Kirkcaldy, in Fife, became the largest producer of linoleum in the world, with no fewer than six floorcloth manufacturers in the town, most notably Michael Nairn & Co., which had been producing floorcloth since 1847.

Walton opened the American Linoleum Manufacturing Company in 1872 on Staten Island, in partnership with Joseph Wild, the company's town being named Linoleumville (renamed Travis in 1930).[2] It was the first U.S. linoleum manufacturer, but was soon followed by the American Nairn Linoleum Company, established by Sir Michael Nairn in 1887 (later the Congoleum Nairn Company, and The Congoleum Corporation of America), in Kearny, New Jersey. Congoleum now manufactures sheet vinyl and no longer has a linoleum line.

In 2016 a Dutch flooring producer changed the old concept of a factory manufactured linoleum in rolls or tiles to a liquid poured version (liquid lino) of the linoleum which is applied seamlessly on site. By adding a hybrid extra vegetable-based binder the liquid lino sets overnight. This hybrid binder system makes the liquid lino highly chemical resistant and permanently flexible.

Loss of trademark protection

Walton was unhappy with Michael Nairn & Co's use of the name Linoleum and brought a lawsuit against them for trademark infringement. However, the term had not been trademarked, and he lost the suit, the court opining that even if the name had been registered as a trademark, it was by now so widely used that it had become generic, only 14 years after its invention. It is considered to be the first product name to become a generic term.[2]

Use

Between the time of its invention in 1860 and its being largely superseded by other hard floor coverings in the 1950s, linoleum was considered to be an excellent, inexpensive material for high-use areas. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was favoured in hallways and passages, and as a surround for carpet squares. However, most people associate linoleum with its common twentieth century use on kitchen floors. Its water resistance enabled easy maintenance of sanitary conditions and its resilience made standing easier and reduced breakage of dropped china.

Other products devised by Walton included Linoleum Muralis in 1877, which became better known as Lincrusta. Essentially a highly durable linoleum wallcovering, Lincrusta could be manufactured to resemble carved plaster or wood, or even leather. It was very successful, and inspired a much cheaper imitation, Anaglypta, originally devised by one of Walton's showroom managers.

Walton also tried integrating designs into linoleum during the manufacturing stage, coming up with granite, marbled, and jaspé (striped) linoleum. For the granite variety, granules of various colours of linoleum cement were mixed together, before being hot-rolled. If the granules were not completely mixed before rolling, the result was marbled or jaspé patterns.

Walton's next product was inlaid linoleum, which resembled encaustic tiles, in 1882. Previously, linoleum had been produced in solid colours, with patterns printed on the surface if required. In inlaid linoleum, the colours extend all the way through to the backing cloth. Inlaid linoleum was made using a stencil type method where different-coloured granules were placed in shaped metal trays, after which the sheets were run through heated rollers to fuse them to the backing cloth. In 1898 Walton devised a process for making straight-line inlaid linoleum that allowed for crisp, sharp geometric designs. This involved strips of uncured linoleum being cut and pieced together patchwork-fashion before being hot-rolled. Embossed inlaid linoleum was not introduced until 1926.

The heavier gauges of linoleum are known as “battleship linoleum”, and are mainly used in high-traffic situations like offices and public buildings. It was originally manufactured to meet the specifications of the U.S. Navy for warship deck covering on enclosed decks instead of wood, hence the name. Most U.S. Navy warships removed their linoleum deck coverings following the attack on Pearl Harbor, as they were considered too flammable. (Use of linoleum persisted in U.S. Navy submarines.) Royal Navy warships used the similar product “Corticine”.

Early in the twentieth century, a group of Dresden artists used easy-to-cut linoleum instead of wood for printmaking, creating the linocut printmaking technique – similar to woodcuts. Prominent artists who created linocut prints included Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Present day

Linoleum has largely been replaced as a floor covering by polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is often colloquially but incorrectly called linoleum or lino. PVC has similar flexibility and durability to linoleum, but also has greater brightness and translucency, and is relatively less flammable. The fire-retardant properties of PVC are due to chlorine-containing combustion products, some of which are highly toxic, such as dioxin.[3]

Notes

- Jones, M.W. (21 Nov 1918). The history and manufacture of floorcloth and linoleum. Society of Chemical Industry.

- Powell and Svendsen, p. 23

- Costner, Pat, (2005), "Estimating Releases and Prioritizing Sources in the Context of the Stockholm Convention" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, International POPs Elimination Network, Mexico.

References

- Powell, Jane; Svendsen, Linda (2003). Linoleum. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1-58685-303-1.

External links

| Look up linoleum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Linoleum. |

- "Resilient Flooring: A Comparison of Vinyl, Linoleum and Cork": Sheila L. Jones, Georgia Tech Research Institute (Fall 1999)

- Dominion Oilcloth and Linoleum Company illustrated catalogue, 1926

- Historic linoleum materials in the Staten Island Historical Society's Online Collections Database