Leading

In typography, leading (/ˈlɛdɪŋ/ LED-ing) is the space between adjacent lines of type; the exact definition varies.

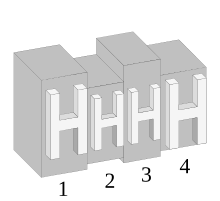

In hand typesetting, leading is the thin strips of lead that were inserted between lines of type in the composing stick to increase the vertical distance between them. The thickness of the strip is called leading and is equal to the difference between the size of the type and the distance from one baseline to the next. For instance, given a type size of 10 points and a distance between baselines of 12 points, the leading would be 2 points.

In electronic typesetting, "leading" often instead means the distance from one baseline to the next.

The term is still used in modern page-layout software such as QuarkXPress, the Affinity Suite, and Adobe InDesign. Consumer-oriented word-processing software often talks of line spacing or, more accurately, interline spacing.

Origins

The word comes from lead strips that were put between set lines of lead type, hence the pronunciation "ledding" and not "leeding". The practice became popular in the eighteenth century.[1]

Practices

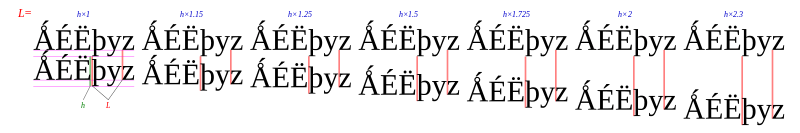

Leading can be used to enhance the legibility of a page or block of text. The standard leading used in printing is usually +2 points for mechanically set body text, or +20% in digital typesetting. In both cases, with a 10 pt font the usual leading is 12 pt, creating a 10/12 ratio, which is considered single spacing.[2] Some type designers recommend a leading between 120% and 145% of the font size.[3]

Double spacing is an entrenched practice due to the era of typewriters and, in academic settings, to allow the addition of handwritten comments and proofreading. Typewriters had a limited number of options for leading, and double spacing was chosen as a default. Double spacing increases the amount of unused white space on a page and reduces the number of lines on a page.[5] Too much leading can cause continuity problems, as the eyes of the reader are required to travel a greater distance between lines of text.[6]

Text set "solid" (no leading) appears cramped, with ascenders almost touching descenders from the previous line. The lack of white space between lines makes it difficult for the eye to track from one line to the next, makes rivers more obvious, and hampers readability.

Issues

Leading can be affected by a series of issues, all of which can be rectified or used to the printer's advantage. A leading that is negative (12/10) could be viewed as a hindrance to readability. It would cause the text to be harder to read, as lines would be forced together, lessening room between lines and hindering readability. However, for short bursts of text a negative leading can enhance the message of the text and can create a more effective text.[2] Negative leading can be affected by ascenders and descenders on certain letters. Letters with high ascenders and low descenders can interfere with one another between lines, if the leading is small enough to allow them to touch one another.[6] Written texts with several portions that demand separate leading can lead to issue of text continuity. Written texts should have a standard leading that does not deviate from page to page. There are instances that call for a change in leading, such as when a block quote is placed within a written text. The lines on the front of a page and the verso (back) should line up vertically, line for line. If there are several leadings contained on one page, this convention can be completely negated. Fonts can also affect the need for leading. No two fonts are exactly alike, and for that reason many have characteristics that demand a certain leading. Fonts that are darker require a wider leading than those that are lighter. As well, fonts that are serif should be leaded wider than those that are sans serif. Languages can decide the leading that a printer uses as well. Leading is an important issue to consider when printing, as it can enhance readability, but it can also affect the number of pages, as larger leadings decrease the number of lines per page. In this way the leading of a page can have a profound effect on the written text.[2]

Examples

This block of text has default leading:

Typography (Greek: typos "form", graphein "to write") is the art and technique of setting written subject matter in type using a combination of typeface styles, point sizes, line lengths, line leading, character spacing, and word spacing to produce typeset artwork in physical or digital form.

The same block of text set with 50% leading is easier to read:

Typography (Greek: typos "form", graphein "to write") is the art and technique of setting written subject matter in type using a combination of typeface styles, point sizes, line lengths, line leading, character spacing, and word spacing to produce typeset artwork in physical or digital form.

The same block of text at 100% leading is again easier to read but makes less efficient use of vertical page space:

Typography (Greek: typos "form", graphein "to write") is the art and technique of setting written subject matter in type using a combination of typeface styles, point sizes, line lengths, line leading, character spacing, and word spacing to produce typeset artwork in physical or digital form.

On the World Wide Web

In CSS, leading refers to the difference between the content height and the value of the line-height property. Half the leading is called the half-leading. User agents center glyphs vertically in an inline box, which adds half-leading on the top and bottom. For example, if a piece of text is "12pt" high and the line-height value is "14pt", 2pt of extra space should be added: 1pt above and 1pt below the text (this applies to empty boxes as well, as if the empty box contained zero-height text).

Feathering

The leading may be increased to align the bottom line of text on a page in a process known as feathering,[7] carding, or vertical justification.

Bastard fonts

In metal typesetting some fonts have default increased or decreased leading. To achieve this, a smaller font face is cast on the body of a larger font or vice versa. Such fonts are usually called "bastard" fonts or types.[8][9] In the notation they are usually written with the face and the body size separated by a slash, like 10/12 that is a 10-point font face on a 12-point body, or 12/10, a 12-point font face on a 10-point body.

See also

References

- Burnhill, Peter (2003). Type spaces: in-house norms in the typography of Aldus Manutius. Hyphen Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-907259-53-4. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

[Quoting a letter from James Mosley]: Leading of text matter for aesthetic reasons is largely an 18th-century (and later) habit...My observations of printing in earlier centuries suggests that the founders generally cast types to fit the body very tightly, and that printers used them without leading.

- Bringhurst., R. (2012). Elements of Typographic Style. Vancouver: Hartley and Marks. ISBN 9780881792126.

- "Butterick's Practical Typography". Matthew Butterick. 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- In Microsoft Word from 97 through 2010; changed to 1.08 in Microsoft Word 2013 and 2016.

- "Butterick's Practical Typography". Matthew Butterick. 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- "The Basics of Typography". Design Instruct. 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Eckersley, R.; et al., eds. (1995). Glossary of Typesetting Terms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 1-281-43121-4.

- Campbel, Alastair (2004). The Digital Designer's Jargon Buster. p. 29.

- Wijnekus, F. J. M.; Wijnekus, E. F. P. H. (1983). Dictionary of the Printing and Allied Industries (2nd ed.). p. 57.