Lincoln Arcade

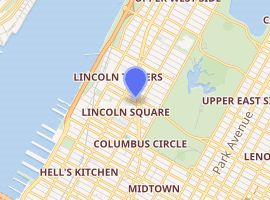

The Lincoln Arcade was a commercial building near Lincoln Square in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City, just west of Central Park. Built in 1903, it was viewed by contemporaries as a sign of the northward extension of business-oriented real estate ventures, and the shops, offices, and other enterprises.

| Lincoln Arcade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Former names | Lincoln Arcade, Lincoln Square Arcade |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial building |

| Town or city | Manhattan |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40.7738°N 73.9828°W |

| Opened | 1903 |

| Destroyed | 1960 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 6 |

| Lifts/elevators | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Julius Munckwitz (1902) |

Soon after it opened, however, the building was becoming known for some considerably less conventional residents. One observer styled some of these newcomers as "starving students, musicians, actors, dead-beat journalists, nondescript authors, tarts, polite swindlers, and fugitives from injustice."[1]:250 Many others were aspiring artists. Most of these men and women received little attention from the public either during their lives or since their deaths, but some, such as George Bellows, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Marcel Duchamp, Eugene O'Neill, and Lionel Barrymore, became famous. The Lincoln Arcade was destroyed in 1960.

History of the site

In the late 1700s the western part of Manhattan where the building would be constructed was known as Bloemendaal or Blooming Dale, the valley of flowers, where could be found large farms.[2] In the early 1800s the city expanded its street network north to the district and the farms that originally dominated the area were broken up into lots that were held as investments.[2] Through inheritance, the location where the Lincoln Arcade would later be built was transferred from the original farm owner, John Somerindyke, to the widow of one of his sons, Abigail Thorn, in 1809.[note 1] Subsequent owners were John H. Talman, John G. Gottsberger, and Thomas S. Cargill.[3]:494 The three were businessmen who held the property along with other real estate investments.[4]

In 1819-20 commissioners named by the state government laid out the street grid for streets, avenues, and the blocks they created.[8] An atlas published in 1868 shows the farms of 1815 overlaid by the 1819-20 grid and atlases published subsequently show the gradual expansion of building construction northward from downtown Manhattan.[9] An 1879 atlas shows lots laid out in the location where the Lincoln Arcade would be built but no buildings put up on them.[10] The atlas published in 1891 shows structures in five of the eight lots in the eventual Lincoln Arcade location. Three had two stories, the other two had one, and they were made of brick.[10] In both editions of the Atlas, John G. Gottsberger is shown as the landowner. Atlases published in 1892 and 1897 show no change but give some detail: At the corner of West 65th Street and Broadway (then called the Boulevard) there were two one-story buildings, one a warehouse, and one two-story commercial building. Near the corner of West 66th Street and the Boulevard there was another two-story warehouse, a coal yard, and, outside the area where the Lincoln Arcade would be erected, a five-story commercial building.[note 3]

In the late 1890s the land and its few structures became increasingly valuable as investors sought property near what had by then become a transportation hub.[note 4] Real estate brokers bought and sold buildings and lots in the location of the future Lincoln Arcade and in 1900 a man named John L. Miller began to assemble the holdings on which he would construct that building.[note 5]

After purchasing some of the property he filed plans to build a four-story brick commercial building on the site, but did not follow through on those plans and instead purchased adjoining lots until he owned nearly the entire block front on Broadway and much of the block at 65th Street near Broadway.[note 6]

Construction and early years

With the property in hand, Miller filed plans to construct what he called the Broadway Arcade. The plans described two buildings of offices and stores situated side-by-side, facing Broadway. The architect was Julius Munckwitz and the expected cost was $215,000.[21] As construction neared completion, a news piece cited it as the keystone of developers' hopes for business-oriented real estate in the vicinity (an area they were now calling "Empire Square"). The article quoted Miller as saying, "I am proving what I think of Empire Square by putting $300,000 in it. We expect to have the Arcade ready by May 1 and already we have rented half the space. I am more than gratified at the outlook. If things pan out as I expect them to, I intend to erect a theatre in the rear of the Broadway Arcade on a plot of six lots I own."[22] An atlas published in 1907 gives a fire insurance perspective on the Arcade. It shows the two buildings, each having six stories, joined by the one-story arcade. Above the arcade, the two structures are connected by a stack of enclosed bridges. At the back of the arcade there is a pair of elevators.[23] In 1916 the New York Times published the sketch of this composite building which can be seen at right. Depicting it as it appeared when new, the sketch shows the pair of buildings and between them an un-roofed alley.[20]

Although first called the Broadway Arcade the building soon came to be known as the Lincoln Square Arcade (after the square of that name located across Broadway from it), and then simply Lincoln Arcade.[note 7] In 1904 Miller formed the Empire Square Realty Company with himself as president and his children as officers and directors. He then placed the Arcade and other holdings in the hands of the new corporation.[27] Miller added a theater to the property the following year. He placed it on 68th Street behind the southern-most of the two Arcade structures and patrons gained access from Broadway via the arcade. It was at first leased by Sam S. and Lee Shubert and called the Lincoln Square Theatre.[28] On May 2, 1907, Charles E. Blaney acquired a 10-year lease from Empire Square Realty, and renamed the theater Blaney's Lincoln Square Theater.[29] Marcus Loew took it over a few years later, rebranded it as Loew's Lincoln Square Theater or simply Loew's Lincoln Square, and used it for both vaudeville and movie shows.[30] The photo at right shows the entrance on Broadway. In performance at the time it was taken were vaudeville acts, mostly song and dance teams, along with impersonators, comedians, and an acrobatic duo called The Bimbos.[31]

By 1918, what was then called the "Lincoln Square District" was said to be unusually profitable for real estate investors, appearing to possess "the qualities for greater building achievements in the years rapidly approaching than those just forgotten."[32]

Miller sought to fill the Arcade with tenants by placing small ads in the local press and in journals such as the Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide.[33] These emphasized "business purposes" such as "stores, studies, offices."[24] They also usually mentioned studios and offered to divide floor space to suit.[34] One mentioned clubrooms.[25] One drew attention to the building's "Most Remarkable Location" with its "Car line and subway and 'L' stations exceeding any point in the city" where could be found "studios, offices and floors, $15 to $100 [with] elevators, steam heat, gas, electricity, baths."[35]

Among street-level tenants during the building's early years were a candy store, a barber, a clock maker, a milliner's shop, a billiard parlor, and two corner saloons.[38] Downstairs was a bowling alley and theater.[39] One of the building's lecture halls hosted a "spiritualistic" enterprise, the First Liberal Thought Church.[40] The upper floors contained stenographers, dance instructors, lawyers, dentists, health faddists, fortune tellers, a school of Jiu-Jitsu, and detective agencies.[39][41]

Although it listed studios, along with offices and stores, as a feature of the building, management did not market the Arcade to artists and other creative arts individuals. It nonetheless attracted many of them. During its early years, in addition to its many artists, it contained the opera star, Rosa Ponselle, the puppeteers, Sue Hastings, Edwin Deaves, and Garrett Becker, the movie director, Rex Ingram, and writers such as William Huntington Wright (S. S. Van Dine) and Thomas Craven.[note 8]

An Australian-born poet, Louis Esson, was one of the first to label this melange a Bohemia. In 1916, he wrote a friend to say, "We have deserted Greenwich Village and the haunts of the Bohemians and have landed near the centre of Broadway (between 65th and 66th streets). As a matter of fact, our present abode is much more Bohemian than Washington Square; at least it is New York's Bohemia. We have a big room in the Lincoln Square Arcade, with steam-heat, electric light, piano, bath, ice-box, elevator, etc."[44] In October of that year, an article in the New York Times contrasted the downtown Bohemia in Greenwich Village with an unexpected Bohemia uptown that was both new and "perhaps more democratic."[20]

Craven, who was an aspiring artist before he established himself as an art critic, considered the building to be the center of metropolitan Bohemian life.[43] He wrote, "The Arcade housed an unsavory crew: commercial artists, illustrators, starving students, musicians, actors, dead-beat journalists, nondescript authors, tarts, polite swindlers, and fugitives from injustice."[1]:250 In his life of John Sloan, Van Wyck Brooks said the building was a "rookery of half-fed students, astrologers, prostitutes, actors, models, prize-fighters, quacks and dancers."[45]

Artists and illustrators

With their large skylights, the top-floor studios attracted artists and illustrators who were able to afford their higher rents. On the other hand, the cheaper studios on the lower floors could often serve, although with mixed success, as both studios and living quarters. The building's relatively prosperous artists and illustrators included Howard Chandler Christy, known for his "Christy Girls"; Dwight Franklin, who built dioramas for the American Museum of Natural History; Charles Henry Niehaus, whose equestrian monuments can be found in many American cities; Bernhardt Wall, an illustrator who became known as the "Postcard King"; and Wilhelm Heinrich Detlev Körner, a prolific illustrator whose painting A Charge to Keep was hung in the Oval Office when George W. Bush was president.[note 9] Of the aspiring artists who tended to occupy the lower floors there were some who failed to gain much recognition during their lives. Women predominated in this group, among them Helyn Knowlton, Molly Wheeler, Charlotta Baxter, and Estelle Orteig.[50] Others, mostly men, fared better in the art world: Robert Henri, George Bellows, Milton Avery, Marcel Duchamp, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Alexander Archipenko, and Raphael Soyer to name a few. One of the more successful tenants later recalled that the building had the reputation of being a good luck spot for budding artists, adding that "many of the great ones had started up the ladder there."[51]:24

In the years between its opening and 1910, Graham F. Cootes, George Bellows, Ted Ireland, Ed Keefe, and Robert Henri took up tenancies.[note 10] In those years Eugene O'Neill roomed with Bellows and set scenes from his 1914 play, "Bread and Butter" there.[55]:132 O'Neill's stage directions describe an artist's studio on the top floor at the front of the building. There is a large bay window overlooking the avenue before which is a comfortable window-seat. The disheveled room is full of unmatched furniture, book cases, a piano, an easel, and many paintings. There is a kitchenette in one corner, partly concealed by a burlap-covered partition, and a small hallway leads to the entrance door. In addition, "There is a large skylight in the middle of the ceiling which sheds the glow from the lights of the city down in a sort of faint half-light."[56]

Artists who arrived between 1911 and 1915 included Glenn Coleman, Henry Glittenkamp, Stuart Davis, Thomas Hart Benton, Raeburn Van Buren, Ralph Barton,:133 and Neysa McMein.[note 11] Benton, Van Buren, and Barton shared their room with the actor, William Powell. Marcel Duchamp and Jean Crotti arrived in 1915.[note 12] In 1916 a group of artists met in the studio rented by A. S. Baylinson to form an organization they called the Society of Independent Artists. The studio became headquarters for the society with Baylinson as secretary. William Glackens was president during its early years, followed by Sloan.[61] Tenants during the 1920s and until the building was demolished included Morris Kantor, Raphael Soyer, Reginald Marsh, Milton Avery, and Alexander Archipenko.[note 13] Early in the 1920s the actors Alfred Lunt and Leslie Howard took drawing lessons from the portraitist, Clinton Peters, in one of the sixth-floor studios and at about the same time John Barrymore rented a studio to try his hand as an artist.[note 14]

Later years

When John L. Miller Sr. died in 1920, John L. Miller Jr. replaced him as head of Empire Square Realty.[67] In 1931, during some of the worst months of the Great Depression, John L. Miller Jr. obtained additional mortgage financing for the Arcade and the additional debt brought his total exposure to $1,250,000.[68] He obtained another loan in 1933 and later in the same year he created a new company which he used to lease the building back to himself for a nominal rent.[note 15] The maneuver clearly failed, for in 1934 he made an unsuccessful attempt to sell the property.[71]

The ravages of the Depression were not his only problems during those years. In February and again in November 1931 the building caught fire leaving parts of it near collapse.[72][73] A photo taken at the time, which can be seen at right, shows the extent of damage to the front of the building. Some artists, including A. S. Baylinson and Helen Sardeau, lost all or most of the works they held there.[74] Sardeau received notice for her pluck in subsequently showing a few pieces she had been able to save in a local exhibition.[75]

The building was quickly rebuilt, but when its tenants had returned the city accused Miller of permitting them to live as well as work in a building that was not registered as a residential structure.[note 16] Miller contested the accusation but failed to prove his case and as a result many people were evicted.[note 17] In 1934 Miller's mortgage holder, City Bank of New York, foreclosed the property and, failing to find a buyer, hired a service company to manage it.[note 18]

A 1939 tax photo, seen at left, shows the building as it appeared following reconstruction. It differed little from its original design, consisting still of two structures that were joined by bridges above a central arcade. In 1942 the bank was finally able to sell the building when an investment syndicate purchased the Arcade and eight adjoining buildings.[78]

In the early 1950s the CBS network took over the theater, renaming it Studio 60. Between 1950 and 1956 shows produced there included the Ernie Kovacs Tuesday night show, the Perry Como Chesterfield Show, the Sammy Kaye Show, and some quiz shows (Strike it Rich, Winner Take All, Break the Bank).[79] A news photo of December 1959 shows no obvious differences in the building from ten years before. It can be seen at right.

When, in the late 1940s, a slum-clearance initiative targeted the area around Lincoln Square, it was at first unclear whether the Arcade would be included in the scheme and it was not until 1958 that the decision was made to raze the building to make way for the new home of the Juilliard School.[80] The following year all of the remaining tenants were evicted, the building was demolished, and construction began.[81] Although the Arcade's Bohemian heyday was by then almost entirely a matter of history, still, looking back on these events, one writer lamented, "The bohemian exuberance that characterized Lincoln Square for so many years was virtually wiped clean in the early 1960s. The giant urban renewal effort that created Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts ironically replaced the popular, underground art scene with the legitimized high culture of musical arts from Europe and America. Although the area would be filled with musicians and artists drawn by the new complex, the economic revival would also force the earlier, more flamboyant group of artists to disperse."[14]

In 1959 Raphael Soyer painted "Farewell to Lincoln Square" to commemorate the eviction of the Arcade's last tenants (shown at left). He later said simply, "This is a picture of the dispossessed."[82] It shows Soyer at back, waving to the viewer, his wife, Rebecca to his right, and, in front, two other Arcade tenants, a jewelry-maker whose name is not given, and Patty Mucha, a painter who was Claes Oldenburg's first wife.[note 19]

Notes

- "Somerindyke,"[3]:428 "1809"[3]:493

- "1891,"[6] "day"[7]

- "1892,"[11] "them"[12]

- "property,"[13] "hub"[14]

- "Arcade,"[13] "building"[15]

- "site,"[16] "lots,"[17] "Broadway"[18][19]

- "Broadway Arcade,"[24] "Lincoln Square Arcade,"[25] "Lincoln Arcade"[26]

- "Ponselle,"[41] "puppeteers,"[42] "Ingram,"[43] "Craven"[1]

- "Christy Girls,"[46] "dioramas,"[47] "equestrian monuments,"[48] "Oval Office"[49]

- "Cootes,"[52] "Bellows," "Ireland," and "Keefe,"[53] "Henri"[54]:189

- "Coleman," "Glittenkamp," "Davis,"[57] "Benton," "Van Buren,"[58] "Barton,"[55] "McMein"[58]

- "Duchamp,"[59] "Crotti"[60]

- "Kantor,"[62] ""Soyer," "Marsh,"[63] "Avery," "Archipenko"[64]

- "studios,"[65] "artist"[66]

- "loan,"[69] "rent"[70]

- "rebuilt,"[67] "structure"[73]

- "case,"[76] "evicted"[66]

- "property,"[77] "manage it"[78]

- "known," "wife"[82][83]

External links

- The Woman Gives: A Story of Regeneration by Owen Johnson (Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1916).

References

- Thomas Craven (1934). Modern Art: The Men, the Movements, the Meaning. Simon and Schuster. p. 250.

- Meyer Berger (April 7, 1958). "About New York: Lincoln Square Once Valley of the Flowers, an 18th Century Eden in Manhattan". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 15.

- H. Croswell Tuttle (1881). Abstracts of farm titles in the City of New York, between 39th and 73rd Streets, west of the common lands, excepting the Glass house farm : with maps. The Spectator Company, New York. p. 648.

- The New York City Directory. C.R. Rode, late Doggett & Rode. 1846.

- "The New System in Use; About a Dozen Transfers Recorded in the Register's Office". New York Times. New York, New York. January 3, 1891. p. 8.

- Atlas of the City of New York; Manhattan Island; From Actual Surveys and Official Plans (Map). Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Limited. 1891. § 116. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Borough-Block-Lot (BBL) Lookup | City of New York". Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Order and Adaptation: What the New York Grid Teaches Us about Contemporary Urbanism". Simon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- The Blue Book, 1815, Drawn From the Original on File in the Street Commissioner's Office in the City of New York; Together with Lines of Streets and Avenues, Laid Out by John Randel, Jr., 1819-1820 (Map). 1868. § 9. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Atlas of the Entire City of New York; Complete in One Volume; From Actual Surveys and Official Records (Map). G.W. Bromley & Co. 1879. § 17. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Insurance Maps of the City of New York (Map). G.W. Bromley & Co. 1892. § 116. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Atlas of the City of New York; Manhattan Island; From Actual Surveys and Official Plans (Map). G.W. Bromley & Co. 1897. § 25. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Third Eno Sale; Properties of the Estate Sold at Auction". New York Evening Post. New York, New York. October 18, 1899. p. 10.

The popularity of Broadway property was further shown in the competition for a plot of four 29- and 28-foot lots at the south-west corner of Broadway and Sixty-fifth Street. This brought out some lively bidding, with the result that Flake Dowling had to pay $177,000 for the offering. Broadway parcels proved the favorite with the bidders throughout the entire sale.

- "History of Lincoln Square, 1700 – 2000". Lincoln Square BID. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "In the Real Estate Field: Southwest Corner Broadway and 65th Street Sold to J.L. Miller". New York Times. New York, New York. April 5, 1900. p. 12.

- "Structures and Alterations". New York Times. New York, New York. May 18, 1900. p. 12.

- "Real Estate Market News; Big Plot in Sixty-fifth Street, Near Empire Square, Changes Hands". New York Times. New York, New York. February 6, 1902. p. 2.

- "Owns Nearly a Block Front". New York Press. New York, New York. April 10, 1902. p. 1.

- "Deal for a Broadway Block". New York Times. New York, New York. April 10, 1902. p. 8.

- Owen Johnson (October 22, 1916). "Owen Johnson Discovers a New Bohemia Here: The Arcade on Lincoln Square Is Held Up as a Rival for the Title So Long Held by the Washington Square Community". New York Times. New York, New York. p. SM9.

- "The Building Department: List of Plans Filed for New Structures and Alterations". New York Times. New York, New York. July 1, 1902. p. 14.

- "In "Empire Square" Is Reflected a Strong Belief in Its Future; the Section, While Many of Its Parcels Are Undeveloped, Has Taken, Nevertheless, a Good Stride in Progress During the Last Year". New York Herald. New York, New York. April 26, 1903. p. 2.

- Insurance Maps of the City of New York Borough of Manhattan (Map). Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Limited. 1907. § 19. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Display Ad: New Building Ready May 1st; Broadway Arcade". New York Times. New York, New York. April 15, 1903. p. 14.

- "Display Ad: Lincoln Square Arcade". New York Times. New York, New York. March 28, 1907. p. 19.

Lincoln Square Arcade, 1947 Broadway, 65th & 66th, Offices, Studios, Clubrooms, Floors, Elevators; steam heat, electric and gas; fine building; most accessible location in city; very reasonable rates.

- "Display Ad". New York Times. New York, New York. October 6, 1908. p. 14.

- "Real Estate Transfers". New York Times. New York, New York. February 14, 1902. p. 14.

- Walter H. Kill (November 3, 1906). "Broadway Topics". Billboard. New York, New York. p. 8.

- "Blaney Gets Lincoln Square", New York Tribune (May 3, 1907)

- "New Playhouse for the West Side; Realty Man to Erect $175,000 Theatre in Sixty-fifth Street, Off Broadway; To Be Called the Arcade". Morning Telegraph. New York, New York. July 27, 1905. p. 10.

- "Display Ad". New York Times. New York, New York. October 1, 1911. p. 13.

- "Many Kinds of Buildings in Lincoln Square District Lincoln Square of Long Ago and To-Day Centre Has Proved to Be a Place Where Many Kinds of Buildings Have Been Profitably Erected and Maintained —Experts Expect Section Will Become More Enticing to Realty Buyers". New York Tribune. New York, New York. February 7, 1918. p. 1.

- Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. F. W. Dodge Corporation. 1903. p. 759.

- "Display Ad: To Let for Business Purposes; Broadway Arcade". New York Times. New York, New York. May 12, 1903. p. 15.

- "Display Ad: New York's Most Remarkable Location". New York Times. New York, New York. October 3, 1909. p. 18.

Car line and subway and "L" stations exceeding any point in the city. Studios, offices and floors, $15 to $100. Elevators, steam heat, gas, electricity, baths. Lincoln Square Arcade, Geo. Washington Martin, 1,947 B'way, 66th.

- Owen Johnson (1916). The Woman Gives: A Story of Regeneration. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4656-0301-2.

- "Beorge Bellows, American, 1882-1925, Club Night, 1907" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- James Bone (April 12, 2016). The Curse of Beauty: The Scandalous & Tragic Life of Audrey Munson, America's First Supermodel. Simon and Schuster. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-942872-03-0.

- Wallace Harrison (1959). "Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York". speech at the University Club. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "Lincoln Square". New York Clipper. New York, New York. April 6, 1912. p. 9.

- Paul Harrison (January 8, 1935). "Sidelights of New York". Saratogian. Saratoga, New York. p. 4.

- Paul McPharlin; Marjorie Batchelder McPharlin; Marjorie Hope Batchelder (1969). The puppet theatre in America: a history, 1524-1948. Plays, inc. p. 270.

- "Rex Ingram: Sculptor, Artist, Writer". Trinity College Dublin. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Peter Fitzpatrick (December 11, 1995). Pioneer Players: The Lives of Louis and Hilda Esson. CUP Archive. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-521-45010-2.

- Van Wyck Brooks (1955). John Sloan: A Painter's Life. E.P. Dutton. p. 42.

- "Howard Chandler Christy". Illustration History. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- "Dwight Franklin". Box Dioramas.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- "Bernhardt Wall - Artist, Fine Art, Auction Records, Prices, Biography for Bernhardt T. Wall". Askart.com. February 9, 1956. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- Scott Horton (January 24, 2008). "The Illustrated President". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- "Broadway Painters Exhibit; Newly Formed Group Has First Display". New York Sun. New York, New York. June 26, 1942. p. 15.

- The World of Comic Art. 1966. p. 24.

- "Cootes, F. Graham (1879–1960)". Encyclopedia of Virginia. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Robert M. Dowling (October 28, 2014). Eugene O'Neill: A Life in Four Acts. Yale University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-300-21059-0.

- Bennard B. Perlman (July 26, 2012). Painters of the Ashcan School: The Immortal Eight. Courier Corporation. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-486-15849-5.

- Justin Wolff (March 13, 2012). Thomas Hart Benton: A Life. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-374-19987-6.

- Eugene O'Neill (1914). Bread and Butter. University of Pennsylvania Libraries Online Books Page. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Stuart Davis". ArtNet. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- "Remembering Raeburn Van Buren". Yesterday's Papers. December 17, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- "Marcel Duchamp". Warholstars. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- Journal of the Archives of American Art. Archives of American Art. 1982. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- "The Society of Independent Artists at the Delaware Art Museum". The Magazine Antiques. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Homer Boss; Susan S. Udell (1994). Homer Boss: The Figure and the Land. Chazen Museum of Art. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-932900-36-4.

- Ellen Wiley Todd (January 1, 1993). The "new Woman" Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street. University of California Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-520-07471-2.

- "Milton Avery: then & now". New Criterion. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Margot Peters (December 18, 2007). Design for Living: Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-307-42551-5.

- Sam Love (December 19, 1931). "New York, Inside Out". Citizen Advertiser. Auburn, New York. p. 2.

- Christopher Gray (October 2, 2005). "The Story of a Name, the Tale of a Co-op". New York Times. New York, New York.

- "$1,250,000 Lien on Broadway Block". New York Times. New York, New York. February 5, 1931. p. 43.

- "Manhattan Mortgages". New York Times. New York, New York. November 4, 1933. p. 31.

- "Recorded Leases". New York Sun. New York, New York. November 7, 1933. p. 23.

- "Theatre on Auction List". New York Times. New York, New York. May 14, 1934. p. 33.

- "Fire Ruin Near Collapse". New York Times. New York, New York. February 1, 1931. p. 23.

Everything seems to have moved uptown, even Bohemia, which for so long a time was pointed out to tourists as being located in Washington Square and Greenwhich Village. It has been praised by some of its literary citizens who tarried there a while, notably O. Henry, who used these art centres in several stories. A new and perhaps more democratic Bohemia has been discovered, however, by Owen Johnson, in his new book, "The Woman Gives," published by Little, Brown & Co., in perhaps the last location one would expect it—in the block-long Arcarde at Lincoln Square.

- "Burned Arcade Is Court Issue; Was Condemned for Dwelling Purposes on Oct. 6; Motion to Make This Permanent to be Argued Nov. 20". New York Sun. New York, New York. November 11, 1931. p. 24.

- "A. S. Baylinson, 68, Art Leader, Dead: Ex-Secretary of Independent Society Had Shown His Work in Leading U.S. Galleries". New York Times. New York, New York. May 7, 1950. p. 106.

- Morton C. Rustus (March 6, 1931). "Fire Fails to Balk Girl's Art Exhibit; Helene Sardeau, Belgian Sculptress, Victim of Arcade Blaze, Shows Three Works; Rest Went Up in Flames". New York Evening Post. New York, New York. p. 7.

- "Incendiary Hunted in Fire Fatal to 5: Three Others Still in Critical Condition Following Blaze in Brooklyn Tenement. Lincoln Arcade Inquiry Continued. Fails to Find Clues. Reports on Arcade Building". New York Times. New York, New York. November 12, 1931. p. 22.

- "2 Theatres Sold on Auction Block". New York Times. New York, New York. August 4, 1934. p. 23.

- "Investors Acquire Lincoln Sq. Arcade: Store and Theatre Blockfront on Broadway Has Assessed Value of $1,790,000". New York Times. New York, New York. September 2, 1942. p. 136.

- "The History of CBS New York Television Studios, 1937-1965" (PDF). eyesofageneration.com. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- Charles Grutzner (March 5, 1958). "Lincoln Sq. Unit Asks More Space: City Weighs Art Center Plan to Add Another Block on Broadway to Project". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 33.

- "33 Ordered Evicted at Arts Center Site". New York Times. New York, New York. June 18, 1958. p. 25.

- Paul Richard (December 5, 1979). "Soyer's Portraits of Intimate Celebrations". Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. B3.

- "Patty [Oldenberg] Mucha Archive". Granary Books. Retrieved April 13, 2019.