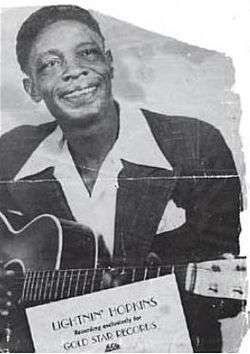

Lightnin' Hopkins

Samuel John "Lightnin'" Hopkins (March 15, 1912 – January 30, 1982)[1] was an American country blues singer, songwriter, guitarist and occasional pianist, from Centerville, Texas. Rolling Stone magazine ranked him number 71 on its list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time.[2]

Lightnin' Hopkins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Sam John Hopkins |

| Born | March 15, 1912 Centerville, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | January 30, 1982 (aged 69) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Genres | Electric blues, country blues, Texas blues |

| Occupation(s) | Guitarist, singer-songwriter |

| Instruments | Guitar, piano, organ, vocals |

| Years active | 1946–1982 |

| Labels | Aladdin, Modern, RPM, Gold Star, Sittin' in With/Jax, Mercury, Decca, Herald, Folkways, World Pacific, Vee-Jay, Arhoolie, Bluesville, Tradition, Fire, Candid, Imperial, Prestige, Verve, Jewel |

The musicologist Robert "Mack" McCormick opined that Hopkins is "the embodiment of the jazz-and-poetry spirit, representing its ancient form in the single creator whose words and music are one act".[3]

Life

Hopkins was born in Centerville, Texas,[4] and as a child was immersed in the sounds of the blues. He developed a deep appreciation for this music at the age of 8, when he met Blind Lemon Jefferson at a church picnic in Buffalo, Texas.[5] That day, Hopkins felt the blues was "in him". He went on to learn from his older (distant) cousin, the country blues singer Alger "Texas" Alexander.[5] (Hopkins had another cousin, the Texas electric blues guitarist Frankie Lee Sims, with whom he later recorded.[6]) Hopkins began accompanying Jefferson on guitar at informal church gatherings. Jefferson reputedly never let anyone play with him except young Hopkins, and Hopkins learned much from Jefferson at these gatherings.

In the mid-1930s, Hopkins was sent to Houston County Prison Farm; the offense for which he was imprisoned is unknown.[5] In the late 1930s, he moved to Houston with Alexander in an unsuccessful attempt to break into the music scene there. By the early 1940s, he was back in Centerville, working as a farm hand.

Hopkins took a second shot at Houston in 1946. While singing on Dowling Street in Houston's Third Ward (which would become his home base), he was discovered by Lola Anne Cullum of Aladdin Records, based in Los Angeles.[5] She convinced Hopkins to travel to Los Angeles, where he accompanied the pianist Wilson Smith. The duo recorded twelve tracks in their first sessions in 1946. An Aladdin executive decided the pair needed more dynamism in their names and dubbed Hopkins "Lightnin'" and Wilson "Thunder".

Hopkins recorded more sides for Aladdin in 1947. He returned to Houston and began recording for Gold Star Records. In the late 1940s and 1950s he rarely performed outside Texas, only occasionally traveling to the Midwest and the East for recording sessions and concert appearances. It has been estimated that he recorded between eight hundred and a thousand songs in his career. He performed regularly at nightclubs in and around Houston, particularly on Dowling Street, where he had been discovered by Aladdin. He recorded the hit records "T-Model Blues" and "Tim Moore's Farm" at SugarHill Recording Studios in Houston. By the mid- to late 1950s, his prodigious output of high-quality recordings had gained him a following among African Americans and blues aficionados.

In 1959, the blues researcher Mack McCormick contacted Hopkins, hoping to bring him to the attention of a broader musical audience engaged in the folk revival.[5] McCormack presented Hopkins to integrated audiences first in Houston and then in California. He made his debut at Carnegie Hall on October 14, 1960, alongside Joan Baez and Pete Seeger, performing the spiritual "Mary Don't You Weep". In 1960, he signed with Tradition Records. The recordings which followed included his song "Mojo Hand" in 1960.

In 1968, Hopkins recorded the album Free Form Patterns, backed by the rhythm section of the psychedelic rock band 13th Floor Elevators. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, he released one or sometimes two albums a year and toured, playing at major folk music festivals and at folk clubs and on college campuses in the U.S. and internationally. He toured extensively in the United States[3] and played a six-city tour of Japan in 1978.

Hopkins was Houston's poet-in-residence for 35 years. He recorded more albums than any other bluesman.[3]

Hopkins died of esophageal cancer in Houston on January 30, 1982, at the age of 69. His obituary in the New York Times described him as "one of the great country blues singers and perhaps the greatest single influence on rock guitar players."[7]

His Gibson J-160e "hollowbox" is on display at the Rock Hall of Fame in Cleveland, and his Guild Starfire at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC, both on loan from the Joe Kessler collection.

Musical style

Hopkins's style was born from spending many hours playing informally without a backing band. His distinctive fingerstyle technique often included playing, in effect, bass, rhythm, lead, and percussion at the same time. He played both "alternating" and "monotonic" bass styles incorporating imaginative, often chromatic turnarounds and single-note lead lines. Tapping or slapping the body of his guitar added rhythmic accompaniment.

Much of Hopkins's music follows the standard 12-bar blues template, but his phrasing was free and loose. Many of his songs were in the talking blues style, but he was a powerful and confident singer. Lyrically, his songs expressed the problems of life in the segregated South, bad luck in love and other subjects common in the blues idiom. He dealt with these subjects with humor and good nature. Many of his songs are filled with double entendres, and he was known for his humorous introductions to songs.

Some of his songs were of warning and sour prediction, such as "Fast Life Woman":

You may see a fast life woman sittin' round a whiskey joint,

Yes, you know, she'll be sittin' there smilin',

'Cause she knows some man gonna buy her half a pint,

Take it easy, fast life woman, 'cause you ain't gon' live always...[3]

References in popular culture

A statue of Hopkins sits in Crockett, Texas.[8]

Hopkins is mentioned in Erykah Badu's 2010 "Window Seat": "I don't want to time-travel no more, I want to be here. On this porch I'm rockin', back and forth like Lightnin' Hopkins."

R.E.M. included the song "Lightnin' Hopkins" on their 1987 album Document.

Hopkins's song "Back to New Orleans (Baby Please Don't Go)" was performed by the fictional country singer Cherlene in the FX television comedy Archer (season 5, episode 1).The rock band AC/DC also covered the song.

Discography

Early compilations of previously issued material

- Early Recordings (Arhoolie, 1946-50 [1969]) - collection of Gold Star recordings

- Early Recordings Vol. 2 (Arhoolie, 1946-50 [1971]) - collection of Gold Star releases

- Lightnin' Hopkins Strums the Blues (Score, 1946-48 [1958]) - collection of Aladdin releases

- Lightning Hopkins Sings the Blues (Crown, 1947-1951 [1961]) - collection of RPM releases

- Last of the Great Blues Singers (Time, 1950-51 [1960]) - collection of Sittin' in With releases

- Lightnin' and the Blues (Herald, 1954 [1960]) - collection of Herald releases

- Blues Masters: The Very Best Of Lightnin' Hopkins (Rhino, 2000) - later collection.

Original LP releases

- The Rooster Crowed in England (77, 1959 [1960])

- Lightnin' Hopkins (Folkways, 1959) - reissued as The Roots of Lightnin' Hopkins

- Country Blues (Tradition, 1959)

- Autobiography in Blues (Tradition, 1960)

- Down South Summit Meetin' (World Pacific, 1960) with Brownie McGhee, Big Joe Williams and Sonny Terry - reissued as Summit Meetin'

- Last Night Blues (Bluesville, 1960) with Sonny Terry

- Lightnin' (Bluesville, 1960)

- Lightnin' in New York (Candid, 1960)

- Mojo Hand (Fire, 1960 [1962])

- Blues in My Bottle (Bluesville, 1961)

- Blues Hoot (Horizon, 1961 [1963]) with Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry - reissued as Coffee House Blues

- On Stage (Imperial Records,[1962]) reissued Dolchess 2013

- Lightnin' Sam Hopkins (Arhoolie, 1962)

- Walkin' This Road by Myself (Bluesville, 1962)

- Lightnin' and Co. (Bluesville, 1962)

- Smokes Like Lightning (Bluesville, 1962 [1963])

- Lightnin' Strikes (Vee-Jay, 1962)

- Hootin' the Blues (Prestige Folklore, 1962 [1965])

- Goin' Away (Bluesville, 1963)

- The Swarthmore Concert (Prestige, 1964 [1993])

- Down Home Blues (Bluesville, 1964)

- Soul Blues (Prestige, 1964 [1965])

- Lightning Hopkins with His Brothers Joel and John Henry / with Barbara Dane (Arhoolie, 1964 [1966])

- My Life in the Blues (Prestige, 1964 [1965])

- Live at the Bird Lounge (Guest Star, 1964)

- The King of the Blues (Pickwick, 1965) - reissued as Let's Work Awhile

- Blue Lightnin' (Jewel, 1965 [1967])

- Live at Newport (Vanguard, 1965 [2002])

- Lightnin' Strikes (Verve Folkways, 1965 [1966]) - reissued as Nothin' But the Blues

- Something Blue (Verve Folkways, 1967)

- Thats My Story (Polydor, 1965 [1970])

- Blues Festival Song & Dance (Arhoolie, 1967) shared disc with Mance Lipscomb and Clifton Chenier

- Texas Blues Man (Arhoolie, 1967)

- Free Form Patterns (International Artists, 1968)

- Talkin' Some Sense (Jewel, 1968)

- Lightnin' Hopkins Strikes Again (Home Cooking, 1968 [1975])

- The Great Electric Show and Dance (Jewel, 1969)

- California Mudslide (and Earthquake) (Vault Records, 1969)

- Lightnin'! (Poppy, 1969) - rereleased on Arhoolie in 1993

- In the Key of Lightnin' (Tomato, 1969 [2002])

- Lightning Hopkins in Berkeley (Arhoolie, 1969 [1970])

- Po' Lightnin' (Arhoolie, 1961/69 [1983])

- The Legacy of the Blues Vol. 12 (Sonet, 1974 [1977])

- New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival 1976 (Island, 1977) shared disc with various artists

- The Rising Sun Collection Vol. 9 (Just a Memory, 1977 [1996])

- Mighty Crazy (Catfish, 1980 [2002]) shared disc with Big Mama Thornton

- The Rising Sun Collection (Just a Memory, 1980 [1996]) shared disc with Louisiana Red, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee

- Forever (Paris Album, 1981 [1983])

Films

- The Blues Accordin' to Lightnin' Hopkins (1968), directed by Les Blank and Skip Gerson (Flower Films & Video)

- The Sun's Gonna Shine (1969), directed by Les Blank with Skip Gerson (Flower Films & Video)

- Sounder (1972), directed by Martin Ritt (the soundtrack includes Hopkins singing "Jesus Will You Come by Here")

- As of 2010, a film documentary on Hopkins, Where Lightnin' Strikes, was in production with Fastcut Films of Houston.

- His song "Once a Gambler" is on the soundtrack of the 2009 film Crazy Heart.

Books

- Mojo Hand: An Orphic Tale, by J.J. Phillips (Serpent's Tail)

- Lightnin’ Hopkins: Blues Guitar Legend, by Dan Bowden

- Deep Down Hard Blues: Tribute to Lightnin', by Sarah Ann West

- Lightnin' Hopkins: His Life and Blues, by Alan Govenar (Chicago Review Press)

- Mojo Hand: The Life and Music of Lightnin' Hopkins, by Timothy J. O'Brien and David Ensminger (University of Texas Press)

References

- Inline citations

- Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 294. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- "Lightnin' Hopkins | Rolling Stone Music | Lists". Rollingstone.com. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 64. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- Nicholas, A. X. (1973). Woke Up This Mornin': Poetry of the Blues. Bantam Books. p. 87.

- Allmusic biography

- Dahl, Bill. "Frankie Lee Sims: Biography". AllMusic.com. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- Saxon, Wolfgang (February 1, 1982). "Obituary: Sam (Lightnin') Hopkins, 69; Blues Singer and Guitarist". New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Russell, pp. 145–146.

- Further reading

- Stambler, Irwin; Landon, Grellun (1983). The Encyclopedia of Folk, Country & Western Music (2nd ed.). St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-24818-0.

- Liner notes to the CD Country Blues, Ryko/Tradition Records.

External links

- Blues Foundation Hall of Fame Induction, 1980

- Houston Chronicle article about dedication of Lightnin' Hopkins statue

- Hopkins feature on Big Road Blues

- Campstreetcafe.com. Accessed December 25, 2007.

- Lightnin' Hopkins on IMDb

- Where Lightnin Strikes (documentary film)

- New York Times obituary