Liberty of Thomas Court and Donore

The Liberty of Thomas Court and Donore (also known as the Earl of Meath's Liberty) was one of several manors, or liberties, that existed in County Dublin, Ireland since the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the 12th century. They were adjacent to Dublin city, and later entirely surrounded by it, but still preserving their own separate jurisdiction.

| Manors of County Dublin |

|---|

| The Liberties in Dublin City |

|

Thomas Court and Donore St. Sepulchre Deanery of St Patrick |

| Manors outside the city |

|

Glasnevin Kilmainham |

Originally the liberty was reckoned part of the barony of Uppercross. In 1774 it was erected into a separate barony called the Barony of Donore.[1] The liberty's privileges were abolished in 1840, and the barony was abolished in 1842, when the area was transferred from the county to the city.[2]

History

The origin of this liberty goes back to the founding of the church of St. Thomas in what is now Thomas St., near St. Catherine's church, in 1177. The founder was William FitzAldelm, deputy and kinsman of King Henry II. The church was dedicated to Thomas à Beckett (St. Thomas the Martyr), who had recently been murdered in his cathedral at Canterbury by followers of the king. The church, which became a rich and powerful monastery, was for the use of the Canons of the Congregation of St. Victor.[3]

In 1195 the head of Hugh de Lacy, who had been killed in 1187, was sent by the Irish for burial to the Abbey of St. Thomas. His body was buried by the Irish in Bective Abbey, County Meath. A long controversy was then carried on between the two abbeys for his body, which was finally settled in favour of St. Thomas in 1205.[4]

In 1380 the Parliament forbade Irishmen from professing in this abbey.

In 1538 Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries. At this time the Abbey of St. Thomas Court held 56 rectories, 2,197 acres (8.89 km2) of land, 67 houses, 47 messuages and 19 gardens. Most of the land was in Meath and Kildare. These possessions were distributed among several people, of which Sir William Brabazon (ancestor of the Earl of Meath) and Richard St. Leger were the major beneficiaries.[5] On 31 March 1545 Sir William Brabazon was granted the lands of the Abbey, with all jurisdictions, liberties, privileges, and so on. This grant was confirmed in 1609 to Sir Edward, his son.[6]

In 1579 the city of Dublin claimed the abbey to be within the jurisdiction and liberty of the city, but they lost their case. From then on the head of the liberty was the Earl of Meath.

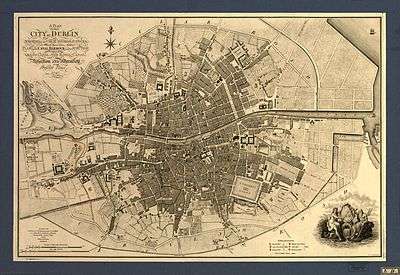

Location

The liberty was located on the south side of the city. It included the parish of St. Luke (just off The Coombe, Dublin) and three-quarters of the parish of St. Catherine (surrounding Thomas Street) (both, of course, Church of Ireland, or civil, parishes). It was divided into four wards: Upper Coombe, Lower Coombe, Thomas Court and Pimlico.[5]

Privileges

In return for the support of the prior of the abbey, or to alleviate certain hardships suffered by Englishmen or the church in Ireland, privileges were granted to the abbey. These allowed the abbey to have its own courts of justice, where it were allowed to try a limited number of crimes, mainly dealing with bad debts. The Earl of Meath inherited these privileges.[7]

The court-house, located in Thomas Court Bawn, was used as a church in the 1760s while St. Catherine's was being renovated, and later was used as a Sunday school. In 1809 the seneschal of the court-house was the renowned historian James Whitelaw, who was also vicar of St. Catherine's. The building fell into decay in the latter half of the century and was demolished in 1897.[8]

These rights and privileges were ended by the Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840.

Administration

The officers of the manor consisted of a seneschal, registrar and marshal, who were appointed by the Earl of Meath. The court-house was located in Thomas Court Bawn, off Thomas Street, while the gaol was in Marrowbone Lane.[5]

In 1813 the population of this manor was 4,639 males and 6,271 females.[9]

References

Sources

- Clarke, H.B. (2016) [2002]. Dublin, part I, to 1610. Irish Historic Towns Atlas. 11 (Online ed.). Royal Irish Academy.

- For medieval liberty boundaries see "Map 4, Historical Map for Dublin, c.840–1540" (PDF). Retrieved 10 May 2018.

Citations

- Act of the Parliament of Ireland of 2 June 1774 (13 & 14 Geo.III c.34)

- Dublin Baronies Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c.96)

- The Abbey of St. Thomas the Martyr, near Dublin, by Anthony L. Elliott, 1892

- M'Gregor, A New Picture of Dublin, 1821

- Dalton: A New Picture of Dublin, Dublin, 1835.

- Miles V. Ronan: The Reformation in Dublin. London, 1926. p. 196

- Parliamentary Papers: Reports from Commissioners, Vol. 24. Session: 4 February - 20 August 1836. House of Commons, London.

- Máirín Johnston, Around the Banks of Pimlico, Attic Press, 1985, ISBN 0-946211-16-7

- Government figures quoted in M'Gregor, Picture of Dublin (1821), p. 62