Liber physiognomiae

Liber physiognomiae (Classical Latin: [ˈliːbɛr pʰʏsɪ.ɔŋˈnoːmɪ.ae̯], Ecclesiastical Latin: [ˈliber fizi.oˈɲomi.e]; The Book of Physiognomy)[nb 1] is a work by the Scottish mathematician, philosopher, and scholar Michael Scot concerning physiognomy; the work is also the final book of a trilogy known as the Liber introductorius. The Liber physiognomiae itself is divided into three sections, which deal with various concepts like procreation, generation, dream interpretation, and physiognomy proper.

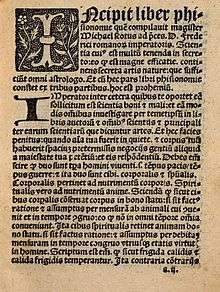

The information found in the Liber physiognomiae seems to have been derived largely from Arabic copies of Aristotelian and Pseudo-Aristotelian works. The work was written in the early 13th century for Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor. It was first printed in 1477. Liber physiognomiae would go on to be very popular, and would be reprinted many times. Scot's work had a major influence on physiognomy itself, and heavily affected how it would be approached and applied in the future.

Background

Liber physiognomiae was written by the Scottish mathematician Michael Scot (AD 1175 – c. 1232) and is the final entry in a divination-centered trilogy, collectively titled the Liber introductorius (The Great Introductory Book).[nb 2] This trilogy also includes the Liber quatuor distinctionum (The Book of the Four Distinctions) and the Liber particularis (The Singular Book).[4][5][6][7]

Contents

—Liber physiognomiae, Introduction, translated by Lynn Thorndike[8]

Liber physiognomiae, as the title suggests, concerns physiognomy, or a technique by which a person's character or personality is deduced based on their outer appearance. Scot refers to this as a "doctrine of salvation" (Phisionomia est doctrina salutis), as it easily allows one to determine if a person is virtuous or evil.[9][10] The book is relatively short, comprising about sixty octavo pages.[5] The work is usually divided into around one hundred chapters, with the number of chapters and their divisions differing greatly depending on what manuscript is being consulted.[8]

While the chapter headings vary across manuscripts, scholars are in agreement that the work is made up of three distinct sections. The first of these deals with the concepts of procreation and generation, largely according to the doctrines of Aristotle and Galen.[11][12] This section opens by stressing the important influence of the stars before it deals with topics concerning human sexual intercourse. The book then moves onto the topics of conception and birth, and the author then explores the physical signs of pregnancy. The final two chapters of this section deal with animals; the penultimate chapter focuses on "animals in genere et in specie" (i.e. in regards to genus and species),[nb 3] while the final details an idiosyncratic system for differentiating the various types of animals.[14]

The second section begins to focus specifically on physiognomy, considering different organs and body regions that index the "character and faculties" of individuals.[11][12][15] Early chapters in this portion of the book are written in a medical style, and they detail signs in regards to "temperate and healthy bod[ies] ... repletion of bad humours and excess of blood, cholera, phlegm, and melancholy", before turning to particular sections of the body.[15] Several following chapters discuss dreams and their meanings. Scot argues that dreams are: true or false; represent past, present, or future events; or are entirely meaningless.[16] The second section comes to an end with chapters concerning auguries and sneezes, respectively.[17]

The third and final section covers body parts, and explicates what the characteristics of these portions may reveal about the nature of the person in question.[12] The final chapter in this section warns the would-be physiognomist to withhold judgement based solely on one part of their body, but rather to "tend always to a general judgement based on the majority of all [the person's] members."[18] This is because another part which has not been consulted may readily counter a conclusion suggested by a part that has. Scot also argues that a physiognomist should take into account a person's "age, long residence in one place, long social usage, excessive prevalence of the humours of his complexion beyond what is customary, accidental sickness, violence, accidents contrary to nature, and a defect of one of the five natural senses."[18]

Sources

According to the physiognomy scholar Martin Porter, the Liber physiognomiae is a "distinctly Aristotelian" compendium of "the more Arabic influenced 'medical' aspects of natural philosophy."[19][20] Indeed, it seems likely that Scot made use of several Aristotelian and Pseudo-Aristotelian works in the writing of the Liber physiognomiae, many of which were derived from Arabic copies. The first of these is an Arabic translation of the Historia Animalium.[21] The second is the Kitāb Sirr al-Asrār (Arabic: كتاب سر الأسرار; known in Latin as the Secreta Secretorum), an Arabic text that purports to be a letter from Aristotle to his student Alexander the Great on a range of topics, including physiognomy.[22][nb 4] The third of these works is Physiognomonics, also attributed to Aristotle and, as the title suggests, also about physiognomy; the influence of this Pseudo-Aristotelian work, according to Haskins, is "limited to the preface" of the Liber physiognomiae.[23][21] Scot probably used the original Greek version of Physiognomonics to write his book.[nb 5] The historian Charles Homer Haskins argues that the Liber physiognomiae also "makes free use" of Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (also known as Rhazes) and shows "some affinities" with Trotula texts and writers of the Schola Medica Salernitana (a medical school located in the Italian town of Salerno).[23]

Publication history and popularity

The work was written sometime in the early 13th century, and is explicitly dedicated to Frederick II. The scholar James Wood Brown argues that the book was likely written for the soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in AD 1209 on the occasion of his wedding to Constance of Aragon.[25] Brown also adds, "No date suits this publication so well as 1209, and nothing but the urgent desire of Court and people that the marriage should prove fruitful can explain, one might add excuse, some passages of almost fescennine license which it contains."[26] The philosophy and religion scholar Irven Resnick argues that the work was given to Frederick so that "the emperor [might be able] to distinguish, from outward appearances, trustworthy and wise counselors from their opposite numbers."[27]

While manuscripts of the Liber quatuor distinctionum and the Liber particularis exist, the Liber physiognomiae was the only book from the Liber introductorius trilogy to be professionally printed, with a first print of the book being released in 1477.[28][29] Between the date of its official printing and 1660, the work was reprinted eighteen times in many languages; this popularity of the text led Rudolf Hirsch (a book scholar) in 1950 to call the book one of the Middle Ages' "best sellers".[29][30] The number of reprints and its wide circulation is attributed in large part to the advent of the printing press in 1440.[12] Among the many reprints, there is little evidence of textual changes, which is unique for manuscripts published and then transmitted in the fifteenth century.[31]

The Liber physiognomiae was often bundled with other, topically-similar texts. For instance, some copies of Scot's book were combined with a work by pseudo-Albertus Magnus entitled De secretis mulierum (Concerning the Secrets of Women), which, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, suggests the opinion of the time was that Scot "dealt with forbidden subjects, or at least subjects better left to medical science."[32] Extracts from the Liber physiognomiae also appear in many early printed versions of Johannes de Ketham's medical treatise Fasciculus Medicinae (although this is not the case for all early copies).[33] Finally, in 1515 a compendium titled Phisionomia Aristotellis, cum commanto Micaelis Scoti was published, which featured the Liber physiognomiae of Scot, alongside physiognomical works by Aristotle and Bartolomeo della Rocca.[34]

Impact

According to Porter, Scot's Liber physiognomiae was influential for three main reasons: First, Scot developed a number of physiognomical aphorisms.[35] Given the popularity of the Liber physiognomiae, Scot's new formulations and ideas, according to Porter, "introduce[d] some fundamental changes into the structure and nature of the physiognomical aphorism."[36] (Effectively, what Scot did was add new meanings to various physical features, making the physiognomical signs discussed in the Liber physiognomiae more complex and, as Porter writes, "polyvalent.")[35] Second, Scot developed a "stronger conceptual link between physiognomy, issues of hereditary, embryology, and generation, which he articulated through astrological ideas of conception."[36] Porter argues that this was done because the book was written by Scot to help Frederick II pick a suitable wife (and thus, by extension, produce a suitable heir).[36] Third and finally, Scot's Liber physiognomiae seems to be the first physiognomical work that takes smell into account. According to Porter, this "totalization" of physiognomy—that is, connecting it to a variety of subjects like reproduction and sense perception—was the most dramatic change that occurred in the way that physiognomy was practiced "as it developed in the period between classical Athens and late fifteenth-century Europe".[37]

Footnotes

- This work is also known as De physiognomia et de hominis procreatione (Classical Latin: [deː pʰʏsɪ.ɔŋˈnoːmɪ.aː ɛt deː ˈhɔmɪnɪs proːkrɛ.aːtɪˈoːnɛ], Ecclesiastical Latin: [de fizi.oˈɲomi.a et de ˈominis prokreatsiˈone]; Concerning Physiognomy and Human Procreation) and the Physionomia. During the Renaissance it was often referred to as De secretis nature (Classical Latin: [deː seːˈkreːtiːs naːˈtuːrae̯], Ecclesiastical Latin: [de seˈkretis naˈture]; Concerning the Secrets of Nature).[1]

- Some sources refer to the first book in the trilogy as the Liber introductorius,[2] whereas other sources specify that the first book is the Liber quatuor distinctionum and that Liber introductorius is the name of the trilogy as a whole.[3]

- In his biology, Aristotle used the term γένος (génos) to mean a general 'kind' and εἶδος (eidos) to mean a specific form within a kind. For instance, "bird" would be a génos, whereas an eagle would be an eidos. Génosand eidos were later translated into Latin as "genus" and "species", though they do not correspond to the Linnean terms thus named.[13] Given that Scot was writing before the Linnean terms were developed, his use of the words "genus" and "species" retain their Aristotelian meanings.

- James Wood Brown argues it is "beyond question" that Scot used the Latin-translation of this text, the Secretum Secretorum, in writing the Liber physiognomiae; Haskins, on the other hand, argues that Scot's work is related to the Latin version only "through a common Arabic source".[23][22] Lynn Thorndike seems to favor Haskins hypothesis, aruging "Michael, himself a translator of long standing from the Arabic, could have made direct use of the Arabic text ... Other evidence makes it more likely that Philip knew of Michael's Physiognomy and that his translation of Secreta secretorum was subsequent to it."[18]

- Because it is believed that the first Latin version of the Physiognomonics was translated directly from the original Greek by Bartholomew of Messina several years after Scot's Liber physiognomiae was written,[21][24] and because no Arabic translation of the work is known to exist, the fact that several passages in Scot's book correspond to passages from Bartholomew of Messina's Latin version of the Physiognomonics suggests that the two were working from the same (Greek) source. This is evidence that Scot had a working knowledge of Greek.[21]

References

- Resnick (2012), p. 15.

- Examples includes: Edwards (1985); Kay (1985), p. 7.

- Examples include: Meyer (2010); Pick (1998), p. 96; Resnick (2012), p. 15, note 10.

- Resnick (2012), p. 15, note 10.

- Kay (1985), p. 5.

- Kay (1985), p. 7.

- Scott & Marketos (2014).

- Thorndike (1965), p. 87.

- Resnick (2012), p. 16.

- Resnick (2012), p. 16, note 11.

- Baynes & Smith (1891), p. 491.

- Brown (1897), p. 39.

- Leroi (2014), pp. 88–90.

- Thorndike (1965), pp. 87–88.

- Thorndike (1965), p. 88.

- Thorndike (1965), p. 89.

- Thorndike (1965), p. 90.

- Thorndike (1965), p. 91.

- Porter (2005), p. 122.

- Porter (2005), p. 69.

- Brown (1897), p. 38.

- Brown (1897), pp. 32–37.

- Haskins (1921), p. 262.

- Knuuttila & Sihvola (2013), p. 5.

- Brown (1897), p. 30.

- Brown (1897), pp. 30–31.

- Resnick (2012), pp. 15–16.

- Thorndike (1965), p. 35.

- Turner (1911).

- Hirsch (1950), p. 119.

- Hellinga (1998), p. 409.

- Stephen (1897), p. 61.

- Porter (2005), p. 94.

- Porter (2005), p. 107.

- Porter (2005), pp. 69–70.

- Porter (2005), p. 70.

- Porter (2005), pp. 70–71.

Sources

- Baynes, Thomas Spencer; Smith, W. Robertson, eds. (1891). "Scot, Michael". Encyclopædia Britannica (9 ed.). London, UK: A & C Black. pp. 469–70.

- Brown, James Wood (1897). An Enquiry Into the Life and Legend of Michael Scot. Edinburgh, Scotland: D. Douglas.

An Enquiry Into the Life and Legend of Michael Scot.

- Edwards, Glenn M. (1985). "The Two Redactions of Michael Scot's 'Liber Introductorius'". Traditio. 41: 329–340. doi:10.1017/s0362152900006942. JSTOR 27831175.

- Haskins, Charles H. (1921). "Michael Scot and Frederick II". Isis. 4 (2): 250–75. doi:10.1086/358033. hdl:2027/hvd.32044014196075. JSTOR 224248. (subscription required)

- Hellinga, Lotte (1998). "BSA Annual Address: A Meditation on the Variety in Scale and Context in the Modern Study of the Early Printed Heritage". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. Bibliographical Society of America. 92 (4): 401–26. JSTOR 24304137. (subscription required)

- Hirsch, Rudolf (1950). "The Invention of Printing and the Diffusion of Alchemical and Chemical Knowledge". Chymia. 3: 115–41. doi:10.2307/27757149. JSTOR 27757149. (subscription required)

- Kay, Richard (1985). "The Spare Ribs of Dante's Michael Scot". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press (103): 1–14. JSTOR 40166404. (subscription required)

- Knuuttila, Simo; Sihvola, Juha (2013). Sourcebook for the History of the Philosophy of Mind: Philosophical Psychology from Plato to Kant. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 9789400769670.

- Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- Meyer, Christian (2010). "Music and Astronomy in Michael Scot's Liber Quatuor Distinctionum". Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge. 76 (1): 119–177. doi:10.3917/ahdlm.076.0119. Retrieved December 30, 2016. (subscription required)

- Pick, Lucy (1998). "Michael Scot in Toledo: Natura Naturans and the Hierarchy of Being". Traditio. 53: 93–116. doi:10.1017/s0362152900012095. JSTOR 27831961. (subscription required)

- Porter, Martin (2005). Windows of the Soul: Physiognomy in European Culture 1470–1780. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780199276578.

- Resnick, Irven M. (2012). Marks of Distinctions: Christian Perceptions of Jews in the High Middle Ages. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1969-1.

- Scott, T. C.; Marketos, P. (November 2014). "Michael Scot". University of St Andrews. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1897). Dictionary of National Biography. 51. London, UK: Macmillan Publishers.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1965). Michael Scot. Edinburgh, Scotland: Thomas Nelson Printers. ISBN 9781425455057.

- Turner, William (1911). "Michael Scotus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York City, NY: Robert Appleton Company – via New Advent.

![]()

![]()