Levite's concubine

The episode of the Levite's concubine is a biblical narrative in Judges 19–21. It concerns a Levite from Ephraim and his concubine, who travel through the Benjaminite city of Gibeah and are assailed by a mob, who wish to sodomize the Levite. He turns his concubine over to the crowd, and they rape her until she dies. The Levite dismembers her corpse and presents the remains to the other tribes of Israel. Outraged by the incident, they swear that none shall give his daughter to the Benjaminities for marriage, and launch a war which nearly wipes out the clan, leaving only 600 surviving men. However, the punitive expedition is overcome by remorse, fearing that it will cause the extinction of an entire tribe. They circumvent the oath by pillaging and massacring the city of Jabesh-Gilead, none of whose residents partook in the war or in the vow, and capturing its 400 maidens for the Benjaminites. The 200 men still lacking women are subtly allowed to abduct the maidens dancing at Shiloh.

Biblical account

The outrage at Gibeah

A Levite from the mountains of Ephraim had a concubine, who left him and returned to the house of her father in Bethlehem in Judah.[1] Heidi M. Szpek observes that this story serves to support the institution of monarchy, and the choice of the locations of Ephraim (the ancestral home of Samuel, who anointed the first king) and Bethlehem, (the home of King David), are not accidental.[2]

According to the King James Version and the New International Version, the concubine was unfaithful to the Levite; according to a note in the Septuagint[3] and in the New Living Translation she was "angry" with him.[4] Rabbinical interpretations say that the woman was both fearful and angry with her husband and left because he was selfish, putting his comfort before his wife and their relationship,[5] and the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges argues that the translation as 'angry' "suits the context, which implies a quarrel, but not unfaithfulness, on the woman’s part".[3] The Levite travelled to Bethlehem to retrieve her, and for five days her father managed to persuade him to delay their departure. On the fifth day, the Levite declined to postpone their journey any longer, and they set out late in the day.

As they approached Jebus (Jerusalem), the servant suggested they stop for the night, but the Levite refused to stay in a Jebusite city, and they continued on to Gibeah. J. P. Fokkelman argues that Judges 19:11–14 is a chiasm, which hinges on the Levite referring to Jebus as "a town of aliens who are not of Israel." In doing this, the narrator is hinting at the "selfishness and rancid group egotism" of the Levite. Yet, it is not the "aliens" of Jebus who commit a heinous crime, but Benjaminites in Gibeah.[6]

They arrived in Gibeah just at nightfall. The Levite and his party waited in the public square, but no one offered the customary hospitality. Eventually, an old man came in from working in the field and inquired as to their situation. He, too was from the mountains of Ephraim, but had lived among the Benjaminites for some time. He invited them to spend the night at his house rather than the open square. He brought him into his house, and gave fodder to the donkeys; they washed their feet, and ate and drank.[7]

Suddenly certain men of the city surrounded the house and beat on the door. They spoke to the master of the house, the old man, saying, "Bring out the man who came to your house, that we may know him." "To know" is probably a euphemism for sexual intercourse here, as in other biblical texts and as the NRSV translates it.[8]

The Ephraimite host offered instead his own maiden daughter and the Levite's concubine. Ken Stone observes, "Apparently the sexual violation of women was considered less shameful than that of men, at least in the eyes of other men. Such an attitude reflects both the social subordination of women and the fact that homosexual rape was viewed as a particularly severe attack on male honor."[8]

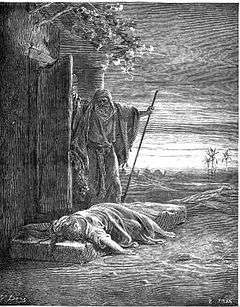

When the men would not be dissuaded, the Levite thrust the concubine out the door. They abused her all night, not letting her go until dawn, when she collapsed outside the door, where the Levite found her the next morning. Finding her unresponsive, he placed her on a donkey and continued his journey home. The account does not state when or where the woman died.[8] Upon his return, he carved up her body into twelve pieces which he sent to all the Israelite tribes, demanding revenge.[9]

The war against Benjamin

Outraged, the confederated tribes mobilized to demand justice and gathered a combined force of about 400,000 confederated Israelites at Mizpah. They sent men through all the tribe of Benjamin, demanding that they deliver up the men who committed the crime to be executed, but the Benjaminites refused and decided to go to war to defend the men of Gibeah instead. They gathered a rebel Benjaminite force of 26,000 to defend Gibeah. According to Judges 20:16, among all these soldiers there were seven hundred select troops who were left-handed, each of whom could sling a stone at a hair and not miss. When the Tribe of Benjamin refused to surrender the guilty parties, the rest of the tribes marched on Gibeah.[9]

On the first day of battle the confederated Israelite tribes suffered heavy losses. On the second day Benjamin went out against them from Gibeah and cut down thousands of the confederated Israelite swordsmen.[9]

Then the confederated Israelites went up to the house of God. They sat there before the Lord and fasted that day until evening; and they offered burnt offerings and peace offerings before the Lord. (The ark of the covenant of God was there in those days, and Phinehas the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron, stood before it.) And the Lord said, "Go up, for tomorrow I will deliver them into your hand."[10]

On the third day the confederated Israelites set men in ambush all around Gibeah. They formed into formation as before and the rebelling Benjaminites went out to meet them. The rebelling Benjaminites killed about thirty in the highways and in the field, anticipating another victory where unaware of the trap that had been set as the confederated Israelites appeared to retreat and the Benjaminites were drawn away from the city to the highways in pursuit, one of which goes up to Bethel and the other to Gibeah. Those besieging the city sent up a great cloud of smoke as a signal, and the Israelite main force wheeled around to attack. When the Benjaminites saw their city in flames, and that the retreat had been a ruse, they panicked and routed toward the desert, pursued by the confederated Israelites. About 600 survived the onslaught and made for the more defensible rock of Rimmon where they remained for four months. The Israelites withdrew through the territory off Benjamin, destroying every city they came to, killing every inhabitant and all the livestock.[11]

Finding new wives

According to the Hebrew Bible, the men of Israel had sworn an oath at Mizpah, saying, "None of us shall give his daughter to Benjamin as a wife."[12]

Then the people came to the house of God, and remained there before God till evening. They lifted up their voices and wept bitterly, and said, "O Lord God of Israel, why has this come to pass in Israel, that today there should be one tribe missing in Israel?"[12]

So it was, on the next morning, that the people rose early and built an altar there, and offered burnt offerings and peace offerings. The children of Israel said, "Who is there among all the tribes of Israel who did not come up with the assembly to the Lord?" For they had made a great oath concerning anyone who had not come up to the Lord at Mizpah, saying, "He shall surely be put to death." And the children of Israel grieved for Benjamin their brother, and said, "One tribe is cut off from Israel today. What shall we do for wives for those who remain, seeing we have sworn by the Lord that we will not give them our daughters as wives?" And they said, "What one is there from the tribes of Israel who did not come up to Mizpah to the Lord?" And, in fact, no one had come to the camp from Jabesh Gilead to the assembly. For when the people were counted, indeed, not one of the inhabitants of Jabesh Gilead was there. So the congregation sent out there twelve thousand of their most valiant men, and commanded them, saying, "Go and strike the inhabitants of Jabesh Gilead with the edge of the sword, including the women and children. And this is the thing that you shall do: You shall utterly destroy every male, and every woman who has known a man intimately." So they found among the inhabitants of Jabesh Gilead four hundred young virgins who had not known a man intimately; and they brought them to the camp at Shiloh, which is in the land of Canaan. Then the whole congregation sent word to the children of Benjamin who were at the rock of Rimmon, and announced peace to them. So Benjamin came back at that time, and they gave them the women whom they had saved alive of the women of Jabesh Gilead; and yet they had not found enough for them. And the people grieved for Benjamin, because the Lord had made a void in the tribes of Israel.[12]

Then the elders of the congregation said, "What shall we do for wives for those who remain, since the women of Benjamin have been destroyed?" And they said, "There must be an inheritance for the survivors of Benjamin, that a tribe may not be destroyed from Israel. However, we cannot give them wives from our daughters, for the children of Israel have sworn an oath, saying, 'Cursed be the one who gives a wife to Benjamin.'" Then they said, "In fact, there is a yearly feast of the Lord in Shiloh, which is north of Bethel, on the east side of the highway that goes up from Bethel to Shechem, and south of Lebonah." Therefore, they instructed the children of Benjamin, saying, "Go, lie in wait in the vineyards, and watch; and just when the daughters of Shiloh come out to perform their dances, then come out from the vineyards, and every man catch a wife for himself from the daughters of Shiloh; then go to the land of Benjamin. Then it shall be, when their fathers or their brothers come to us to complain, that we will say to them, 'Be kind to them for our sakes, because we did not take a wife for any of them in the war; for it is not as though you have given the women to them at this time, making yourselves guilty of your oath.'" And the children of Benjamin did so (on Tu B'Av); they took enough wives for their number from those who danced, whom they caught. Then they went and returned to their inheritance, and they rebuilt the cities and dwelt in them. So the children of Israel departed from there at that time, every man to his tribe and family; they went out from there, every man to his inheritance.[12]

According to the Book of Judges 20:15–18, the strength of the armies numbered 26,000 men on the Benjamin side (of whom only 700 from Gibeah), and 400,000 men on the other side.[13]

Rabbinical interpretation

R. Ebiathar and R. Yonatan explained that this incident shows that a person should never abuse his household, for in this narrative it resulted in the death of tens of thousands of Israelites in the ensuing warfare. What happens within the small family unit is reflective of society as a whole, and marital peace is the basis for every properly functioning society.[5] According to some rabbinical commentators, Phineas sinned due to his not availing his servitude of Torah instruction to the masses at the time leading up to the battle of Gibeah.[14] In addition, he also failed to address the needs of relieving Jephthah of his vow to sacrifice his daughter.[15] As consequence, the high priesthood was taken from him and temporarily given to the offspring of Ithamar, essentially Eli and his sons.

Scholarly view

Traditionally the story of the Concubine of a Levite and the preceding story of Micah's Shrine have been seen as supplemental material appended to the Book of Judges in order to describe the chaos and depravity to which Israel had sunk by the end of the period of the Judges, and thereby justify the establishment of the monarchy. The lack of this institution ("At that time, there was no king in Israel") is repeated a number of times, such as Judges 17:6; 18:1; 19:1; and 21:25.[2]

Yairah Amit in The Book of Judges: The Art of Editing, concluded that chapters 19–21 were written by a post-exilic author whose intent was to make the political statement that Israel works together.[2]

According to scholars, the biblical text describing the battle and the events surrounding it is considerably late in date, originating close to the time of the Deuteronomist's compilation of Judges from its source material, and clearly has several exaggerations of both numbers and of modes of warfare.[16] Additionally, the inhospitality which triggered the battle is reminiscent of the Torah's account of Sodom and Gomorrah.[16][17] Many Biblical scholars concluded that the account was a piece of political spin, which had been intended to disguise atrocities carried out by the tribe of Judah against Benjamin, probably in the time of King David as an act of revenge or spite by David against the associates of King Saul, by casting them further back in time, and adding a more justifiable motive.[16] More recently, scholars have suggested that it is more likely for the narrative to be based on a kernel of truth, particularly since it accounts for the stark contrast in the biblical narrative between the character of the tribe before the incident and its character afterwards.[16]

Feminist interpretation

It is evident that the victimized woman has no voice, as is often the case with rape. According to Brouer, many biblical authors "…highly value women and speak adamantly against rape."[18] The woman stands apart from the other characters in the story by not being given a name or voice.[19] A woman from Bethlehem, she grew up in a family-centered, agrarian society soon after the death of Joshua (Judges 1:1).[18] She had the status of a concubine (Hebrew pilegesh), rather than a wife, to a Levite living in Ephraim.[19] Madipoane Masenya writes

...it appears that she was not an ordinary pilegesh. This is buttressed by the observation that the word 'neerah can be translated as 'newly married woman'. In addition, the 'pilegesh’s father is referred to as 'hatoh' or 'hatan', which literally means, 'he who has a son-in-law', that is, a father-in-law in relation to the pilegesh’s husband, the Levite. I therefore choose to translate the word 'pilegesh' as 'a legitimate wife', one of the wives of the Levite...[19]

Because it was rare for a woman to leave her husband, the narrator uses harsh language to describe the reason for the concubine leaving. She is said to have prostituted herself against her husband.[20] Though it is assumed that she is a prostitute, the Hebrew verb for prostitution, zanah, can also mean "to be angry."[18] It is more plausible that because the Levite spoke harshly towards her, she acted on her own and fled to her father's home where she was welcomed. Therefore, the Levite had to change his way of speaking in order for her to return with him.[19]

Throughout the story, the concubine never has a speaking role. Only the men ever speak, even though the story is centered around a woman. When the Levite stumbles over his concubine in the morning, it is unclear whether she is dead, as there is no reply. When the concubine dies is unknown; whether it was during the brutal night, on the way back to Ephraim, or when the Levite dismembers her body. Because of the Levite's actions,

.jpg)

At a time when there was no king or ruler in Israel, the old man uses the concubine in order to protect the Levite, thinking this was the right thing to do. The men of the city never saw a problem with their actions against the foreigners. The Priscilla Papers, a Christian egalitarian journal, makes mention of the narrative, writing: "By equating 'rape' with doing the 'good in their eyes,' the text makes a powerful rhetorical statement by connecting a key theme throughout Judges with the rape of the concubine: Everyone was doing what was good in their eyes, but evil in God’s eyes."[18]

Judges 19 concludes by saying that nothing like this had happened since the Exodus of the Israelites from Ancient Egypt. Comparing the lamb sacrifice on the doors in Egypt to the concubine on the doorstep using sacrificial language, Brouer furthers the narrator's final statement saying,

…rape, death, and dismemberment of [the concubine are portrayed] as an antithesis of the Passover sacrifice. The narrator concludes Judges 19 with the exhortation to set your heart upon [her], counsel wisely on her behalf, and speak out (Judges 19:30).[18]

See also

- Sati (Hindu goddess), cut into 51 pieces after her death

References

- Judges 19:2

- Szpek, Heidi M., "The Levite’s Concubine: The Story That Never Was", Women in Judaism, Vol.5, No.1, 2007

- Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on Judges 19, accessed 16 November 2016

- Translations of Judges 19:2 at Biblehub.

- Kadari, Tamar. "Concubine of a Levite: Midrash and Aggadah", Jewish Women's Archive.

- J. P. Fokkelman, Reading Biblical Narrative (Leiderdorp: Deo, 1999), 110–11.

- Judges 19

- Stone, Ken. "Concubine of a Levite: Bible", Jewish Women's Archive.

- Arnold SJ, Patrick M., Gibeah: The Search for a Biblical City, A&C Black, 1990 ISBN 978-0-56741555-4

- Judges 20:28

- Judges 20:48

- Judges 21

- Richard A. Gabriel, The Military History of Ancient Israel.

- Yalkut Shimoni, 19,19

- Genesis rabbah, 60,3

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Michael Carden (1999). "Compulsory Heterosexuality in Biblical Narratives and their Interpretations: Reading Homophobia and Rape in Sodom and Gibeah". Journal for the Academic Study of Religion. 12 (1): 48.

discussion of Genesis 19 (and its parallel, Judges 19) is still couched in such terms as 'homosexual rape' and 'homosexuality'. {...}There is a parallel story to Genesis 19 in the Hebrew bible, that of the outrage at Gibeah found in Judges 19-21 which Phyllis Trible (1984) has rightly described as a text of terror for women.{...}Stone acknowledges the relationship of Judges 19 and Genesis 19, describing them as each being one of the few "clear references to homosexuality in the Hebrew Bible" (Stone, 1995:98).{...}In Judges 19, the process is similar but with some interesting differences.

- Brouer, Deirdre (Winter 2014). "Voices of Outrage against Rape: Textual Evidence in Judges 19" (PDF). Priscilla Papers. 28: 24–28.

- Masenya, Madipoane J. (2014-06-03). "Without a voice, with a violated body: Re-reading Judges 19 to challenge gender violence in sacred texts". Missionalia: Southern African Journal of Missiology. 40 (3): 205–214. doi:10.7832/40-3-29. ISSN 2312-878X.

- Ken Stone. "Concubine of a Levite: Bible". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

Further reading

- Bohmbach, Karla G. "Conventions/Contraventions: The Meanings of Public and Private for the Judges 19 Concubine." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, vol. 24, no. 83, 1999, pp. 83–98., doi:10.1177/030908929902408306.

- Szpek, Heidi M. "The Levite's Concubine: The Story That Never Was." Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal, 19 Jan. 2008.