Levi graph

In combinatorial mathematics, a Levi graph or incidence graph is a bipartite graph associated with an incidence structure.[1][2] From a collection of points and lines in an incidence geometry or a projective configuration, we form a graph with one vertex per point, one vertex per line, and an edge for every incidence between a point and a line. They are named for Friedrich Wilhelm Levi, who wrote about them in 1942.[1][3]

| Levi graph | |

|---|---|

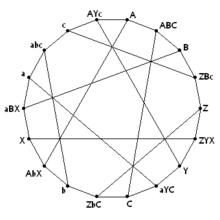

The Pappus graph, a Levi graph with 18 vertices formed from the Pappus configuration. Vertices labeled with single letters correspond to points in the configuration; vertices labeled with three letters correspond to lines through three points. | |

| Girth | ≥ 6 |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

The Levi graph of a system of points and lines usually has girth at least six: Any 4-cycles would correspond to two lines through the same two points. Conversely any bipartite graph with girth at least six can be viewed as the Levi graph of an abstract incidence structure.[1] Levi graphs of configurations are biregular, and every biregular graph with girth at least six can be viewed as the Levi graph of an abstract configuration.[4]

Levi graphs may also be defined for other types of incidence structure, such as the incidences between points and planes in Euclidean space. For every Levi graph, there is an equivalent hypergraph, and vice versa.

Examples

- The Desargues graph is the Levi graph of the Desargues configuration, composed of 10 points and 10 lines. There are 3 points on each line, and 3 lines passing through each point. The Desargues graph can also be viewed as the generalized Petersen graph G(10,3) or the bipartite Kneser graph with parameters 5,2. It is 3-regular with 20 vertices.

- The Heawood graph is the Levi graph of the Fano plane. It is also known as the (3,6)-cage, and is 3-regular with 14 vertices.

- The Möbius–Kantor graph is the Levi graph of the Möbius–Kantor configuration, a system of 8 points and 8 lines that cannot be realized by straight lines in the Euclidean plane. It is 3-regular with 16 vertices.

- The Pappus graph is the Levi graph of the Pappus configuration, composed of 9 points and 9 lines. Like the Desargues configuration there are 3 points on each line and 3 lines passing through each point. It is 3-regular with 18 vertices.

- The Gray graph is the Levi graph of a configuration that can be realized in as a grid of 27 points and the 27 orthogonal lines through them.

- The Tutte eight-cage is the Levi graph of the Cremona–Richmond configuration. It is also known as the (3,8)-cage, and is 3-regular with 30 vertices.

- The four-dimensional hypercube graph is the Levi graph of the Möbius configuration formed by the points and planes of two mutually incident tetrahedra.

- The Ljubljana graph on 112 vertices is the Levi graph of the Ljubljana configuration.[5]

References

- Grünbaum, Branko (2006), "Configurations of points and lines", The Coxeter Legacy, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 179–225, MR 2209028. See in particular p. 181.

- Polster, Burkard (1998), A Geometrical Picture Book, Universitext, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 5, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8526-2, ISBN 0-387-98437-2, MR 1640615.

- Levi, F. W. (1942), Finite Geometrical Systems, Calcutta: University of Calcutta, MR 0006834.

- Gropp, Harald (2007), "VI.7 Configurations", in Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (eds.), Handbook of combinatorial designs, Discrete Mathematics and its Applications (Boca Raton) (Second ed.), Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, pp. 353–355.

- Conder, Marston; Malnič, Aleksander; Marušič, Dragan; Pisanski, Tomaž; Potočnik, Primož (2002), The Ljubljana Graph (PDF), IMFM Preprint 40-845, University of Ljubljana Department of Mathematics.