Leslie Garland Bolling

The sculptor Leslie Garland Bolling (September 16, 1898 – September 27, 1955) was born in Surry County, Virginia, United States on September 16, 1898, the son of Clinton C. Bolling, a blacksmith, and his wife Mary. His carvings reflected everyday themes and shared values of the Black culture in the segregated South in the early 20th century.[2] Bolling was associated with the Harlem Renaissance and is notable as one of a few African-Americans whose sculpture had lasting acclaim.[3]

Leslie Bolling | |

|---|---|

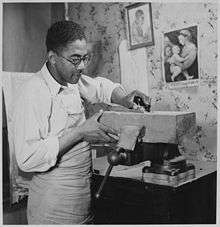

Leslie Bolling preparing a rough block of wood for carving | |

| Born | Leslie Garland Bolling September 16, 1898 |

| Died | September 27, 1955 (aged 57) New York City |

| Resting place | Woodland Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia |

| Education | Hampton Agricultural and Normal Institute (1916–1918) Virginia Union University (?–1924) |

| Alma mater | Virginia Union University |

| Occupation | Sculptor |

| Years active | 1928–1950 |

| Known for | Wood carving |

Notable work | Days of the Week Red Cap |

| Spouse(s) | Julia V. Lightner ( m. 1928)Ethelyn M. Bailey ( m. 1948) |

| Notes | |

Early life

Leslie Bolling's parents were Clinton C. and Mary Bolling. He was born in Dendron, Virginia, a small community in Surry County. His father was a blacksmith.[4]

Bolling spent two years from 1916 to 1918 attending Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, which is now Hampton University and was an institution for upward mobility of African-American youth. Bolling did not have any formal training in art or sculpture although Hampton did have a small arts museum.[1][2]

In 1919 during the Red Summer of race riots, he enrolled in the Academic Department at Virginia Union University, a historically black university in Richmond. In addition to normal academic courses, he also took Manual Training, a course which included both freehand drawing and mechanical drawing. This course involved working with tools using both wood and iron as well as blacksmithing.[2]

After graduating from VUU in June 1924 Bolling began working as a porter at the Everett Waddey Company stationery store.[2] Four years after graduation from VUU, in 1928, Bolling married Julia V. Lightner, his first wife. They did not have any children.[1]

Artistic work

Bolling said he grew up near lumbering operations and was always around trees. Reportedly he enjoyed whittling which would have provided him significant experience with carving various kinds of wood.[5] His carving seems to have been an enjoyable and somewhat profitable hobby, but he viewed himself as a porter or messenger by occupation.[4]

His hobby seems to have taken a serious turn about the time he produced some early figures for a group exhibition sponsored by the YWCA.[4] About 1928 these first figures attracted the interest of Carl Van Vechten, a patron of the Harlem Renaissance movement.[4][6] He began teaching wood carving to black youth in Richmond about 1931. He taught at the Craig House Art Center in Richmond until 1941.[2] By 1938 Bolling and others had obtained WPA sponsorship for the Craig House. It was the only WPA sponsored art center in the segregated South for black youth.[1]:38,281[6]

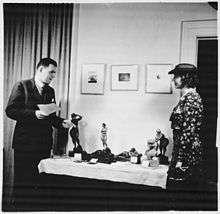

His work began to achieve broader recognition as a result of the National Negro Exhibition of 1933 at the Smithsonian.[1]:38[4] Bolling participated in a number of art tours between 1934 and 1940, managed by the Harmon Foundation to showcase the artistic work of African-Americans.[4]

Reflecting the growing significance of his sculpture, in January 1935, Bolling was honored when the then segregated Academy of Arts in Richmond, now the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts produced a one-man show of his carvings.[2][4] This was followed by a show at the New Jersey state museum.[2][4] Thomas Hart Benton was interested in his work and visited the extended show.[1][7] He described Bolling's works as sculptures that "show real merit, and a new kind of form."

In 1936 he exhibited at the Texas Centennial Exhibition. This was followed by a show at the William D. Cox Gallery in New York in June 1937 of 17 pieces including the recently completed sculpture series Days of the Week which he had begun in 1933.[1]:38[7]

In 1940, Alain Locke included a photograph of Bolling's work in The Negro in Art. Bolling carved a bust of Marian Anderson following an appearance by her in Richmond.[1]:38

Science and Mechanics magazine sponsored a competition in 1942 which Bolling entered and won.[2]

The last known exhibition during his life was a show at State Teachers College at Indiana in 1950.[2]

Bolling's sculpture was included in contemporary books surveying African-American art. His carving was discussed at length in 1940 by E. J. Tangerman. In 2006, the Library of Virginia produced an exhibition of Bolling's work and included material related to 30 of his pieces.[8]:6

Later life

Bolling left Richmond in the early 1940s and moved to Pennsylvania. In 1948 he married Ethelyn M. Bailey, his second wife. After moving to New York City he was represented by the Cox Gallery. Bolling died in New York on September 27, 1955. His body was returned to Richmond, Virginia for burial.[2]

List of sculptures

It is believed Bolling carved 50 to 80 pieces during the two decades he was active.[8] Many of them appear to have been lost. In 2006, the Library of Virginia was able to account for just 30 of his wood sculptures.[9]:1 Following is a partial list of his sculptures.

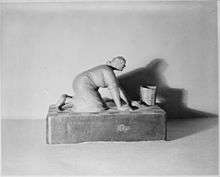

- Days of the Week, composed of seven sculptures created between 1933 and 1936 relating typical weekly activities of African-American servants in the first half of the 20th century.

- Parson-on-Sunday teaching from the Word.

- Aunt Monday doing laundry.

- Sister Tuesday releasing wrinkles.

- Mama-on-Wednesday repairing holes and tears.

- Gossip-on-Thursday with the day off.

- Cousin-on-Friday scouring floors.

- Cooking-on-Saturday for Sunday.

- President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt are twin carvings from 1940.

- Red Cap, showing a porter moving baggage from 1940.

- Marian Anderson is a bust from 1940.

- Save America, a comment on democracy.[2]

- Woman Cooking, depicting a woman cooking on a stove.

References

- Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance at Google Books

- Sandra L. West. "Leslie Garland Bolling". Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art at Google Books

- Creating Black Americans: African-American history and its meanings, 1619 to the Present at Google Books

- "Leslie Bolling – Artist, Fine Art, Auction Records, Prices, Biography for Leslie Garland Bolling". Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "African–American History Month at the Library of Virginia". Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "Library of Virginia – Leslie Garland Bolling Exhibition – Recognition". Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "The Library of Virginia – Official Newsletter – Issue175" (PDF). The Library of Virginia. May–June 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- "The Library of Virginia – Official Newsletter – Issue174" (PDF). The Library of Virginia. March–April 2006. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

External links

- VCU Libraries Through the Lens of Time: Images of African Americans from the Cook Collection of Photographs – Leslie Bolling