Lepidoptera genitalia

The study of the genitalia of Lepidoptera is important for Lepidoptera taxonomy in addition to development, anatomy and natural history. The genitalia are complex and provide the basis for species discrimination in most families and also in family identification.[1] The genitalia are attached onto the tenth or most distal segment of the abdomen. Lepidoptera have some of the most complex genital structures in the insect groups with a wide variety of complex spines, setae, scales and tufts in males, claspers of different shapes and different modifications of the ductus bursae in females.[2][3]

The arrangement of genitalia is important in the courtship and mating as they prevent cross-specific mating and hybridisation. The uniqueness of genitalia of a species led to the use of the morphological study of genitalia as one of the most important keys in taxonomic identification of taxa below family level. With the advent of DNA analysis, the study of genitalia has now become just one of the techniques used in taxonomy.[4]

Configurations

There are three basic configurations of genitalia in the majority of the Lepidoptera based on how the arrangement in females of openings for copulation, fertilisation and egg-laying has evolved:[1]

- Exoporian : Hepialidae and related families have an external groove that carries sperm from the copulatory opening (gonopore) to the (ovipore) and are termed Exoporian.

- Monotrysian : Primitive groups have a single genital aperture near the end of the abdomen through which both copulation and egg laying occur. This character is used to designate the Monotrysia.

- Ditrysian : The remaining groups have an internal duct that carry sperm and form the Ditrysia, with two distinct openings each for copulation and egg-laying.

Male

Genitalia in male and female of any particular Lepidopteran species are adapted to fit each other like a lock (female) and key (male).[4] In males, the ninth abdominal segment is divided into a dorsal 'tegumen' and ventral 'vinculum'.[5] They form a ring-like structure for the attachment of genital parts and a pair of lateral clasping organs (claspers, valvae (singular valva), or 'harpes'). The male has a median tubular organ (called aedeagus or phallus) which is extended through an eversible sheath (or 'vesica') to inseminate the female.[3] The males have paired sperm ducts in all Lepidopterans; however, the paired testes are separate in basal taxa and fused in advanced forms.[3]

The males of many species of Papilionoidea are furnished with secondary sexual characteristics. These consist of scent-producing organs, brushes, and brands or pouches of specialised scales. These presumably meet the function of convincing the female that she is mating with a male of the correct species.[6]

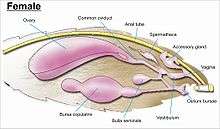

Female

While the layout of internal genital ducts and openings of the female genitalia depends upon the taxonomic group that insect belongs to, the internal female reproductive system of all Lepidopterans consists of paired ovaries and accessory glands which produce the yolks and shells of the eggs. Female insects have a system of receptacles and ducts in which sperm is received, transported and stored. The oviducts of the female join together to form a common duct (called the 'oviductus communis') which leads to the vagina.[3][5]

When copulation takes place, the male butterfly or moth places a capsule of sperm (referred to as 'spermatophore') in a receptacle of the female (called the 'corpus bursae'). The sperm, when released from the capsule, swims directly into or via a small tube (the 'ductus bursae') into a special seminal receptacle (the 'spermatheca'), where the sperm is stored until it is released into the vagina for fertilisation during egg laying, which may occur hours, days, or months after mating. The eggs pass through the ovipore. The ovipore may be at the end of a modified 'ovipositor' or surrounded by a pair of broad setose anal papillae.[3][5]

Butterflies of the Parnassinae (Family Papilionidae) and some Acraeini (Family Nymphalidae) add a post-copulatory plug, called the sphragis, to the abdomen of the female after copulation preventing her from mating again.[2] The females of some moths have a scent-emitting organ located at the tip of the abdomen.[4]

Gallery

Citheronia regalis with claspers closed.

Citheronia regalis with claspers closed. Citheronia regalis with claspers open.

Citheronia regalis with claspers open..jpg)

.jpg) Close up of the hardened Parnassius sphragis extruding 2 to 3 mm behind the abdomen.

Close up of the hardened Parnassius sphragis extruding 2 to 3 mm behind the abdomen.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lepidoptera genitalia. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Lepidoptera |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lepidoptera. |

References

- Powell, Jerry A. (2009). "Lepidoptera". In Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects (2 (illustrated) ed.). Academic Press. p. 1132. ISBN 978-0-12-374144-8. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Heppner, J.B. (2008). "Butterflies and moths". In Capinera, John L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Gale virtual reference library. 4 (2 ed.). Springer Reference. p. 4345. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Lepidopteran". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, London. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Hoskins, Adrian. "Butterfly Anatomy Head (& other pages)". www.learnaboutbutterflies.com. Retrieved 15 Nov 2010.

- Scoble (1995). Section Adult abdomen, (pp 98 to 102).

- Evans, W.H. (1932). Identification of Indian Butterflies (Free full text download (first edition)) (2 ed.). Mumbai: Bombay Natural History Society. pp. 454 (with 32 plates). Retrieved 14 November 2010.. Section Introduction, (pp 1 to 35).