Leon Smith (naval commander)

Leon Smith (?[lower-alpha 2] – 1869) was an American steamboat captain and soldier. In the American Civil War he served the Confederate States of America as a volunteer; he was named Commander of the Texas Marine Department[lower-alpha 1] under General John B. Magruder. Smith was involved in most major conflicts along the Texas coast during the war,[2][3] and was described by war-time governor of Texas Francis Lubbock as "undoubtedly the ablest Confederate naval commander in the Gulf waters".[4]

Leon Smith | |

|---|---|

Leon Smith in uniform | |

| Nickname(s) | Lion Smith |

| Born | Connecticut or Alfred, Maine |

| Died | 29 October 1869 Wrangell, Alaska |

| Buried | San Francisco or Houston, Texas |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | Unknown 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Unknown Variously described as naval lieutenant, captain, and commodore or army major, and colonel, but not actually commissioned |

| Commands held | Texas Marine Department[lower-alpha 1] |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Personal life and family

Smith's birth date is unknown, and he may have been born either in Connecticut or Alfred, Maine. He was a Freemason, and according to some wartime and post-war reports, Caleb Blood Smith, a cabinet member under President Lincoln, was his half-brother.[3][5][6][4]

Smith was married, and had a son, named Leon B. Smith.[3][7]

Pre-Civil War career

A mariner from the age of 13, by the time he was 20 Smith was in command of the United States mail steamship Pacific that sailed between San Francisco and Panama.[3][4]

According to some sources he served in the Texas Navy during the Republic of Texas period.[8][9][10]

He met John B. Magruder in the late 1840s when engaged in shipping on the West coast. In the 1850s he sailed in the Gulf of Mexico, working for the Southern Mail Steamship Company.[3]

Civil War

1861 – December 1862

In February 1861 he was the captain of the steamer General Rusk and transported General John Salmon Ford and his troops to the mouth of the Rio Grande to receive the surrender of Union Major Fitz John Porter. Unattached to either side, Smith then contracted with Major Porter to transport the Union troops to New York.[3]

In April 1861, back in the Gulf of Mexico, he and his ship General Rusk volunteered for service for the Confederates. On April 18, 1861, Smith and his ship assisted Colonel Earl Van Dorn in the capture of Star of the West (notable for being the target of the first shots of the civil war on January 9, 1861, in Fort Sumter) off Matagorda Bay via trickery: pulling alongside her under the pretense of transferring "friendly" troops which were expected from the transport Fashion.[3][11] Smith reportedly replying to a hail from Star of the West with "The General Rusk with troops on board. Can you take our line now ?" and explaining that the Fashion would be arriving later with the luggage and the rest of the troops. The boarding troops promptly seized the Star of the West at bayonet point.[12]

Between October 1861 and December 1862 Smith and the General Rusk were under the command of CSN Commander William W. Hunter. On 7 November 1861, Smith and the General Rusk extinguished the fire aboard the stricken Royal Yacht following her encounter with USS Santee, and towed her back to port.[3][13]

December 1862 – January 1863: Appointment to command, Battle of Galveston

Following the retreat from Galveston in the Battle of Galveston Harbor (1862), General Paul Octave Hébert was relieved from command and replaced in November 1862 by General John B. Magruder who arrived in Texas.[14] Previously acquainted with Smith, in December Magruder placed Smith in charge of all the steamers at his disposal.[3][15]

On Christmas Day 1862,[16] Smith was charged with hastily improvising the CS Bayou City, CS Neptune, along with the tenders Lucy Gwinn and the John F. Carr for battle as improvised Cottonclad warships. The Bayou City was outfitted with a single 32-pounder rifled cannon and the Neptune with two 24-pounders howitzers. Cotton bales were used to provide a semblance of protection that was somewhat effective in stopping small arm fire, however when asked by a soldier about artillery protection Smith bluntly replied: "None whatsover... our only chance is to get alongside before they hit us". Boarding devices resembling the Roman Corvus were placed on the hurricane deck of each boat.[17] Facing Smith's forces were vastly superior Union naval forces: USS Clifton, USS Harriet Lane, USS Westfield, USS Owasco, USS Corypheus, USS Sachem, and four smaller vessels.[3][18][19]

The attack initially planned for 27 December 1862 was delayed to New Year's Eve, the Battle of Galveston. Smith's force was to attack from sea into the Harbor as General Magruder attacked from land crossing over the railroad trestle connecting the island to the mainland. Smith was to wait to be signaled by gunfire that the battle had begun, which was expected to occur at midnight. However, Magruder's forces were delayed by the difficulty of crossing his artillery over the trestle.[20] After no signal came after midnight passed, Smith pulled back from the harbor to Red Fish Bar, a point fourteen miles away. Hearing the attack commencing at 04:00, Smith directed the naval contingent back to the harbor, probably reaching it an hour after the initial shots were fired.[21]

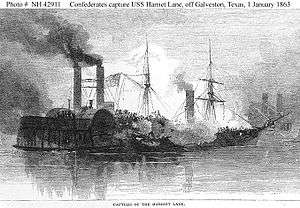

Attacking just before daybreak, the CS Neptune was severely damaged and sunk, but Smith, aboard the CS Bayou City managed to ram into the Harriet Lane, board, and capture her, reportedly personally killing US Navy Commander Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright and recovering a valuable signal book.[6][22] Though still outnumbered, Smith demanded the surrender of US fleet from commander William B. Renshaw, who had run aground aboard the USS Westfield. While under the flag of truce, Renshaw blew up his vessel and died in the explosion.[23] Smith boarded the USS John F. Carr and captured her as well, while the rest of the US Navy ships escaped to sea.[3][24][25][26][27][28] Aboard the captured USS John F. Carr, Smith gave chase to the fleeing Union ships, however the small ship was unable to match the speed of the larger warships. Turning around back to the bay, Smith captured three small Union ships (the Cavallo, Elias Pike, and Lecompte) with their cargo.[29][30][31]

Following the battle, Smith won praise for his gallant conduct,[32] including a mention in a joint resolution of the Congress of the Confederate States.[33] General Magruder attempted to secure a regular Naval commission as commander for him, one of several repeated attempts, which did not result in an actual commission being granted.[3][2]

January 1863 – August 1864

Following the battle, the Confederate States Navy sent Lieutenant Joseph Nicholson Barney to take charge of naval operations in Galveston, including the captured Harriet Lane. However, after discussions with Magruder who was not willing to relinquish control of the cottonclads, Barney conceded the appointment, and in a letter to Confederate naval secretary Stephen Mallory recommended that the Navy relinquish control. Barney later explained that he made his recommendation since he considered that the presence of two separate marine forces with independent commanders would lead to discord and confusion.[34][35][3]

Smith remained in charge of all vessels in Texas, and by order of General Magruder appointed "Commander, Marine Department of Texas".[lower-alpha 1][3]

On September 5, 1863, he was at Orange, Texas, inspecting the Texas and New Orleans Railroad. On September 8 he was at Beaumont, Texas, when a Union force under the command of Major General William B. Franklin with four gunboats, eighteen transports, and 5,000 infantry assaulted up the Sabine River in the Second Battle of Sabine Pass. Smith immediately ordered all Confederate troops in Beaumont, some eighty men, aboard the steamer Roebuck and sent them down the river to reinforce Fort Griffin. Smith and a Captain Good rode to the fort on horseback, reaching the fort some three hours before the steamer, arriving just as the Union gunboats USS Clifton and Sachem came within range of Fort Griffin, which was manned by forty-seven troops. Assisting in the defense of the Fort, Smith took charge of the Clifton and Sachem which were captured during the battle which was one of the most one-sided Confederate victories of the war: no Confederate losses versus 200 killed, wounded or captured Union troops and two lost gunships.[3][36][37][38][39]

From November to December 1863, he was sent by Magruder to direct the naval side of the defense of Indianola, Texas, where Colonel William R. Bradfute was commanding the land forces. As part of the engagement, the Confederates retreated in the Battle of Fort Esperanza. Smith commanded John F. Carr, Cora, and eleven small vessels with sharpshooters and artillery; however disagreements with Bradfute were a hindrance to operations. Smith chose not to take the offensive, fighting defensively.[3][40]

In early 1864 Brig. Gen. William Steele, who was given command of Galveston, attempted to take control of the naval forces there, however Magruder asserted Smith's authority.[3]

In the summer of 1864, due to better land fortifications and the developing state of the war (most Texas troops were transferred to Louisiana in March), the marine contingent was less needed and Smith was relieved from duty at his request by Captain Henry S. Lubbock (the brother of governor Francis Lubbock and who had been the captain of CS Bayou City (Smith's flagship) in the Battle of Galveston)[41] who commanded the marine department sub-district at Galveston. Smith was ordered by Magruder to report "by letter" to the Confederate States Secretary of the Navy.[3]

August 1864 – June 1865

By 1864, Smith was well known by name to Federal authorities. Following a news report in the Houston Daily Telegraph that Smith was going to be sent to London to acquire a fast steamboat for privateering, that was reprinted by New York papers, Federal authorities attempted to disrupt the alleged scheme.[3][42][43][44]

Smith, however, did not depart Texas immediately, and in September 1864 he captured the US schooner Florence Bearn at the mouth of the Rio Grande. In November 1864 he was in Havana where his presence was noted by Union officials, and where he was detained by Spanish authorities for a time. He subsequently piloted the steamer Wren to Galveston through the Union blockade. In an April 1865 letter Magruder writes that Smith will bring in a valuable Confederate steamer probably in the next dark moon.[3][45] On 20 June 1865 he reportedly left Texas with other notable Confederate figures.[46]

Post Civil war

Following the war he was for a time at Havana, then went to San Francisco where his wife and son were living,[3] and was involved in steamer operations along the western coast.[47] Smith was involved in with unsuccessful efforts to introduce petroleum as fuel for steamers. After the failure of this scheme and the Alaska Purchase, in 1868 he freighted a small vessel with goods to Alaska, however this vessel was shipwrecked and little of the cargo was saved.[48] A subsequent trip with a second vessel was successful, and Smith took up residence at Fort Wrangel with his Family.[7] In Fort Wrangel, he operated a trading post and bowling alley in partnership with William King Lear. On October 29, 1869 he was involved in a beating of an Indian who he believed struck his son, Leon B., though later Smith discovered this was not the case.[3]

On 25 December 1869 a Stikine Indian named Lowan bit off Mrs. Jaboc Muller's third right finger, and was killed in an ensuing fight by soldiers who severely wounded an additional Stikine Indian. The following morning, Scutd-doo, who was the father of the deceased, entered the fort and shot Smith fourteen times. Smith died some 13 hours later. The US army made an ultimatum demanding Sccutd-doo's surrender, and following bombardment of the Stikine Indian village, the villagers handed Scutd-doo over to the military in the fort, where he was court-martialed and publicly hanged before the garrison and assembled natives on 29 December,[49][50] stating before he was hanged that he had acted in revenge against the occupants of the fort for the killing of Lowan and not against Smith in particular.[51][52] Smith's body was sent for burial in San Francisco,[3][53][54][55] and possibly onward to Texas in the city cemetery in Houston.[4]

Notes

- As with Smith's stated rank, naming of the Marine Department varies between sources, periods and even within the same source between (in rough ranking of usage): "Texas Marine Department", "Marine Department, Texas", "Marine Department of Texas", "Marine Department of the Military District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona" or "Marine Department of the Trans-Mississippi District"[1] (the latter two refer to "District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona" which was General John B. Magruder command which is also alternatively Trans-Mississippi in some sources)

- Texas Historical Commission plaque: Commodore Leon Smith at Sabine Pass has his birth year as 1829, and a full first name of Leonidas, however sourcing of this is unclear.

Bibliography

- Hall, Andrew W. (2012). "Chapter 5: The Texas Marine Department". The Galveston-Houston packet: steamboats on Buffalo Bayou. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 9781609495916. OCLC 812531247.

- Lubbock, Francis Richard (1900). Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. Austin, B. C. Jones & co., printers.

References

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1895

- Texas in the Confederacy: military installations, economy, and people, Bill Winsor, 1978, page 80

- Day, James M. (1965) "Leon Smith: Confederate Mariner," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 7.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 432.

- Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, Edward Terrel Cotham, page 107

- GOSSIP FROM RICHMOND, New York Times, 23 Feb 1863

- Daily Alta California, Volume 22, Number 7245, 21 January 1870

- Strangling the Confederacy: Coastal Operations in the American Civil War, Kevin Dougherty, page 27

- Voices of the Confederate Navy: Articles, Letters, Reports, and Reminiscences, R. Thomas Campbell, page 190

- Civil War in Texas and the Southwest, Roy Sullivan, page 77

- Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, Edward Terrel Cotham, page 21-22

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 317.

- BRILLIANT EXPLOIT IN GALVESTON BAY.; Capture of the Privateer Royal Yacht Attempt to Cut Out the Steamer Rusk Resistance of the Rebels Bravery of the National Forces., NY Times, 19 December 1861

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. p. 66.

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. p. 69.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 429.

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. pp. 69–71.

- The United States Gunboat Harriet Lane, Philip C. Tucker, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Apr., 1918), pp. 360–380

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. pp. 432–3, 441.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. pp. 434–5.

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. pp. 72–75.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 436,441–3.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. pp. 436–7.

- The Seventh Star of the Confederacy: Texas During the Civil War, Kenneth Wayne Howell, page 126

- The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, Edward Alfred Pollard, page 365

- Civil War in Texas and the Southwest, Roy Sillivan, page 80

- The Civil War Naval Encyclopedia, Volume 1, Spencer Tucker, page 251

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. pp. 75–77.

- Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, Edward Terrel Cotham, page 130

- Hall. The Galveston-Houston packet. pp. 77–79.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 438.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 439,454.

- THE REBEL CONGRESS.; THANKS TO MAGRUDER., New York Times, 24 February 1863

- Cotham, Edward Terrel (1998). Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston. University of Texas Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 9780292712058.

barney.

- Civil War High Commands, John Eicher & David Eicher, page 893

- Sabine Pass: The Confederacy's Thermopylae, Edward T. Cotham, Jr.

- The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (Complete), Jefferson Davis

- Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States, Volume 11, Clement A. Evans, pages 109–110

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 505.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 532.

- Lubbock. Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, governor of Texas in war time, 1861–63. A personal experience in business, war, and politics. p. 24,441,447,586.

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, United States Naval War Records Office, 1896, pages 379–380, 398

- United States Army and Navy Journal, Volume 2: Various Naval Matters, 1 October 1864, page 93

- Congressional Serial Set: Letter from the Secretary of State to the Secretary of the Navy, regarding the alleged fitting of a cruiser in a British port by Colonel Leon Smith, C.S. Army, page 684

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, United States. War Department, 1896, page 1274

- FROM TEXAS.; Negroes and the Labor Question General Advance in Wages Feelings of the People The Crops Condition of the Country., New York Times, 16 July 1865

- Lewis Dryden's marine history of the Pacific Northwest, E.W. Wright, pages 110, 165, 180

- Daily Alta California, Volume 20, Number 6845, 13 December 1868: THE LOSS OF THE "THOMAS WOODWARD."

- The Aleut Internments of World War II: Islanders Removed from Their Homes by the United States, Russell W. Estlack, page 53

- Harring, Sidney L. "The Incorporation of Alaskan Natives Under American Law: United States and Tlingit Sovereignty, 1867-1900." Ariz. L. Rev. 31 (1989): 279.

- The 1869 Bombardment of Ḵaachx̱an.áakʼw from Fort Wrangell: U.S. Army Response to Tlingit Law, Wrangell, Alaska (Washington DC: American Battlefield Preservation Program; Juneau, AK: Sealaska Heritage Institute, 2015). Part 1, National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program, Zachary Jones

- Report of the commander of the department of Alaska upon the late bombardment of the Indian village at Wrangel, in that Territory, to Congress, Secretary of War, 21 March 1870

- History of Alaska: 1730–1885, Hubert Howe Bancroft, 1886, pages 614–6

- Journal of the West, Lorrin L. Morrison, Carroll Spear Morrison, 1965, page 310

- Daily Alta California, Volume 22, Number 7249, 25 January 1870: An Indian Trouble— A White Man Murdered —Two Indians Killed— The Indian Raneno Shelled— Peace Restored

External links

- Captain Leonidas R Smith Find A Grave.