Leigh Woods National Nature Reserve

Leigh Woods is a 2-square-kilometre (0.77 sq mi) area of woodland on the south-west side of the Avon Gorge, close to the Clifton Suspension Bridge, within North Somerset opposite the English city of Bristol and north of the Ashton Court estate, of which it formed a part. Stokeleigh Camp, a hillfort thought to have been occupied from the third century BC to the first century AD and possibly also in the Middle Ages, lies within the reserve on the edge of the Nightingale Valley. On the bank of the Avon, within the reserve, are quarries for limestone and celestine which were worked in the 18th and 19th centuries are now derelict.

| Leigh Woods | |

|---|---|

The woods in early autumn | |

| |

| Type | Open access woodland |

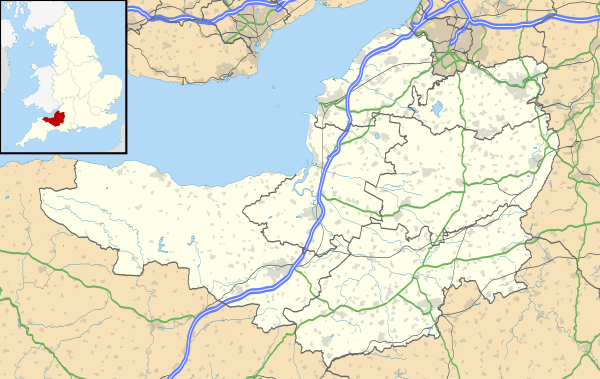

| Location | North Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | |

| Area | 2 square kilometres (490 acres) |

| Operated by | National Trust, Forestry Commission |

| Status | Open all year |

In 1909 part of the woodland was donated to the National Trust by George Alfred Wills, to prevent development of the city beside the gorge following the building of the Leigh Woods suburb. Areas not owned by the National Trust have since been taken over by the Forestry Commission. Rare trees include multiple species of Sorbus with at least nine native and four imported species. Bristol rockcress (Arabis scabra) which is unique to the Avon Gorge can be seen flowering in April; various species of orchids and western spiked speedwell (Veronica spicata) are common in June and July. It is a national nature reserve and is included in the Avon Gorge Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Topography

The woods, which cover an area of 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi), are on a ridge which mainly consists of limestone, with some sandstone which runs from Clifton to Clevedon, 10 miles (16 km) away on the Bristol Channel coast. At the southern end of the woods is Nightingale Valley (one of several thus named in the area), a dry valley which is cut into the side of the gorge.[1] Its area slopes from the highest point nearly opposite the north gate of Ashton Court to the River Avon beside the western buttress of the Clifton Suspension Bridge. The woods are on the Monarch's Way long-distance footpath.[2]

History

Within Leigh Woods is Stokeleigh Camp, a hill fort thought to have been occupied from the third century BC to the first century AD and also in the Middle Ages.[3] It is situated on a promontory,[4] bounding the north flank of the Nightingale Valley and occupying around 7.5 acres (3.0 ha).[5] Stokeleigh Camp is thought to have been occupied from the late pre-Roman Iron Age, when it was in the area controlled by the Dobunni.[6] Archaeological investigations suggest during the 1st century Belgae tribes may have been present with some of the pottery showing the influence of the Durotriges. There may have been a break in occupation before reuse in the middle to late 2nd century.[5] In addition to the pottery recovered a possible coin of Gallienus dating from his reign between 253 and 268 has been recovered. An iron-involuted brooch of the La Tène II type has also been found.[5] It is unclear whether the occupation of Stokeleigh Camp in the 3rd century was for a formal garrison or whether it was just used by "squatters" or as a place of refuge in times of crisis. Stokeleigh might have been connected with the Wansdyke, a series of defensive linear earthworks, consisting of a ditch and an embankment running at least from Maes Knoll in Somerset, to the Savernake Forest near Marlborough in Wiltshire, however there is little evidence for this. It is also possible that the site was occupied in the Middle Ages.[7]

North of Stokeleigh Camp are a series of limestone and mineral quarries, overlooking the River Avon, which are now disused. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries this had an important celestine quarry and a tramway which linked it to a dock on the Avon; both are now derelict.[8][9] The area has in recent years been restored as an arboretum. At the northern end of the woods is Paradise Bottom. This is included in the Leigh Court Estate and was part of the ground laid out by Humphry Repton[10] for Philip John Miles. Some of the first plantings of the giant redwood (Sequoiadendron giganteum) and the Weymouth pine (Pinus strobus), among other "exotics" imported to the UK, were made here by Sir William Miles in the 1860s.[11][12]

To the south of the woods is an affluent suburb of Bristol also known as Leigh Woods. It is situated at the western end of the Clifton Suspension Bridge, which opened in 1864, making the development of Leigh Woods as an upmarket residential area practicable.[13] Houses in varying styles were built from the mid-1860s until the First World War.[14]

In 1857 the mutilated body of a murdered woman was found in Nightingale Valley; the following year, John Beale was hanged at Taunton for the crime in January 1858.[15][16] Another violent death occurred in 1948 when George Henry Chinnock, who had been living in the woods, was found with head injuries.[17]

In 1909 part of the woodland was donated to the National Trust by the tobacco company owner George Alfred Wills.[18] He did this to prevent housing development on the western side of the gorge as Bristol grew in size and population.[19] In 1974 the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food bought the woodland associated with the Leigh Court estate.[20] Areas not owned by the National Trust have since been taken over by the Forestry Commission.[21]

The Portishead Railway runs close to the river at the bottom of the woods. It was opened on 18 April 1867, but closed on 3 April 1981.[22] The Great Western Railway built a small station with the aim of attracting tourists to the area; Nightingale Valley Halt was not very successful and was only in use for less than five years, from 9 July 1928 until 12 September 1932.[23] The line was reopened for freight traffic as far as Royal Portbury Dock on 21 December 2001[24] and local councils are proposing to reintroduce a passenger service to Portishead as part of their MetroWest plans, although this would not happen before 2019.[25]

In 1957 a Filton-based RAF Vampire jet from 501 Squadron crashed into Leigh Woods. The pilot, Flying officer John Greenwood, was killed after he flew under the deck of the suspension bridge while performing a victory roll.[26][27]

Small mountain biking circuits are present in the woods and the area is a popular walking area for Bristolians.[28][29]

Flora and fauna

Because of the rare flora and fauna, the woods have been included in the Avon Gorge Site of Special Scientific Interest, which received the designation in 1952,[30][31] and 140 hectares (350 acres) has been designated as a national nature reserve.[32][33]

The south part of the woods is an area of former pasture woodland with old pollards, mainly oak and some small-leaved lime. To the north, the area comprises ancient woodland of old coppice with standards and contains a rich variety of trees. Rare trees include Bristol whitebeam (Sorbus bristoliensis) and wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis). There are multiple species of Sorbus within the woods with at least nine native and four imported species, making it one of the most important sites in Britain for this tree.[34][35] Birds which live in the woods include the raven (Corvus) and peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). Many butterflies and moths can be seen in summer including the white-letter hairstreak (Satyrium w-album).[36]

On the steep grassy slopes above the River Avon, Bristol rockcress (Arabis scabra) which is unique to the Avon Gorge can be seen flowering in April; orchids and western spiked speedwell (Veronica spicata) are common in June and July.[36] In autumn the woodland hosts over 300 species of fungi.[37][38] Bilberry, a scarce plant in the Bristol area, is found in Leigh Woods, as is the parasitic plant yellow bird's-nest (Monotropa hypopitys).[39] Lady orchid (Orchis purpurea) was discovered here in 1990, in Nightingale Valley; there is doubt as to whether this was a wild plant or an introduction.[40] Green-flowered helleborine (Epipactis phyllanthes) is found on the western side of the gorge, in a wooded area next to the towpath below Leigh Woods.[41]

References

- "Bristol's Great Glacier? Stage 4". Nature. BBC.

- "Walking, Cycling and Mountain Biking". Abbots Leigh. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Leigh Woods". National Trust. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Stokeleigh Camp Hillfort". Hillfort in England in Somerset. Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Historic England. "Stokeleigh Camp (198375)". PastScape. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- "Stokeleigh Camp". English Heritage. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- "Where I Live: Bristol". British Broadcasting Corporation. October 2004. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "The industrial past of Leigh Woods". National Trust. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- "Paradise Bottom". Industrial Railway Society Archive. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "Walking in Leigh Woods" (PDF). Avon Gorge and Downs Wildlife Project. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- "Leigh Woods" (PDF). Forestry Commission. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Victorian Era: The Miles Family". Kings Weston Action Group. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "A History of Long Ashton & Leigh Woods". Long Ashton Community Website. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- "History". Leigh Woods. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "The Murder in Leigh Woods, Bristol". London Standard. 21 September 1857. p. 8. Retrieved 18 May 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The Execution of John Beale for the Murder at Leigh Woods near Bristol". London Standard. 13 January 1958. p. 8. Retrieved 18 May 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Leigh Woods Victim is Bristol Man". Western Daily Press. 15 October 1948. p. 4. Retrieved 18 May 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Leigh Woods: History". National Trust. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Mr George Wills Guft of Leigh Woods". Western Daily Press. 31 March 1909. p. 7. Retrieved 18 May 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Historic England. "Leigh Court (1000407)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Leigh Woods". Forest of Avon. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Oakley, Mike (2002). Somerset Railway Stations. The Dovecote Press. p. 98. ISBN 1904349099.

- Oakley, Mike (2002), p.92

- "Avonside along the Avon side". Avon Valley Railway. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "MetroWest Pahse 1". Travel West. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- Whittell 2007, p. 151.

- Griffiths 2012, p. 61.

- "Leigh Woods Activities". National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Yer Tiz (Leigh Woods)". Bristol Trails Group. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Avon Gorge SSSI" (PDF). Natural England. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Leigh Woods NNR". Natural England. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Leigh Woods". Avon Gorge and Downs Wildlife project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "National Character Area profile:118. Bristol, Avon Valleys and Ridges". Natural England. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Rich, T.C.G.; Houston, L. (2006). "Sorbus whiteana (Rosaceae), a new endemic tree from Britain" (PDF). Watsonia. 26: 1–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Rich, T.G.G.; Houston, L. (2004). "The distribution and population sizes of the rare English endemic Sorbus wilmottiana E. F. Warburg, Wilmott's Whitebeam (Rosaceae)" (PDF). Watsonia. 25: 185–191. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012.

- "Leigh Woods: Wildlife". National Trust. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Leigh Woods NNR" (PDF). Natural England. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "The South West: Gloucestershire, Wiltshire (and the West of England) National Nature Reserves". Natural England. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Myles 2000, p. 108.

- Myles 2000, p. 251.

- Myles 2000, p. 249.

Bibliography

- Awdry, W. (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1852600495.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butt, R.J.V. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1852605087.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, E. (1959). An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles. Cassell. ASIN B000WSRHU6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, Gerald (2012). The Autobiography of an Ex-Grenadier Guardsman: Gerald Griffiths His Life and Military Background. S.l: Authorhouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-4721-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myles, Sarah (2000). The Flora of the Bristol Region. Pisces. ISBN 978-1874357186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whittell, Giles (2007). Spitfire Women of World War II. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-723535-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leigh Woods. |

- Leigh Woods information at the National Trust

- Leigh Woods information at the Forestry Commission

- "Map of Leigh Woods circa 1900". Somerset County Council. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2015.