Leadville mining district

The Leadville mining district, located in the Colorado Mineral Belt, was the most productive silver-mining district in the state of Colorado and hosts one of the largest lead-zinc-silver deposits in the world. Oro City, an early Colorado gold placer mining town located about a mile east of Leadville in California Gulch, was the location to one of the richest placer gold strikes in Colorado, with estimated gold production of 120,000–150,000 ozt (8,200–10,300 lb; 3,700–4,700 kg), worth $2.5 to $3 million at the then-price of $20.67 per troy ounce.[1]

Cumulative production through 1963 was 240 million troy ounces (16 million pounds; 7.5 million kilograms) of silver, three million troy ounces (210 thousand pounds; 93 thousand kilograms) of gold, 987 million tonnes (2.2 trillion pounds; 987 billion kilograms) of lead, 712 million tonnes (1.6 trillion pounds; 712 billion kilograms) of zinc, and 48 million tonnes (110 billion pounds; 48 billion kilograms) of copper. The district also produced byproduct bismuth, and iron-manganese ore.[2]

History

%2C_1833-1880.jpg)

Gold was discovered in the area in late 1859, during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. However the initial discovery, where California Gulch empties into the Arkansas River, was not rich enough to cause excitement. On April 26, 1860, Abe Lee made a rich discovery of placer gold in California Gulch, about a mile east of Leadville, and Oro City was founded at the new diggings.[3][4] By July 1860 the gold rush was on; the town and surrounding area grew to a population of 10,000 and an estimated $2 million in gold (equivalent to $60 million today) was taken out of California Gulch and nearby Iowa Gulch by the end of the first summer. But within a few years the richest part of the placers had been exhausted and the population of Oro City dwindled to only several hundred. Many claims were consolidated, and worked by ground sluicing. A ditch was dug in 1877 to provide water for hydraulic mining, but the hydraulic mining was reported to be unsuccessful.[5]

In 1874, gold miners at Oro City had an assay done on the heavy, black sand that had been impedeing their placer gold recovery and found that it was the lead mineral cerussite, that carried a high content of silver. Prospectors traced the cerussite to its source, and by 1876 had discovered several lode silver-lead deposits, setting off the Colorado Silver Boom. Unlike the gold which was in placer deposits, the silver was in veins in bedrock and hard rock mining was needed for recovery of the ore.

The city of Leadville was founded near to the new silver deposits in 1877 by mine owners Horace Austin Warner Tabor and August Meyer,[6] By 1878 Leadville had become the county seat of Lake county. The name Leadville probably was chosen for the town because lead was the major mineral in both the placers and in the lode mines. By 1880, millions of dollars were being made and Leadville became one of the world's largest silver camps with a population of over 40,000. Leadville became Colorado's largest mining camp and the town was second only to Denver. Leadville became overcrowded, unable to support the hundreds of miners that were flooding into the area. There was no local food source and all supplies had to come by either pack mules or the stage coach. Exorbitant prices were being charged for a place to sleep.

Leadville is a high mountain town and the winters are long and bitterly cold; many miners died of exposure and starvation. Crime was rampant and lawmen were unable to cope with it. Many small shanty towns grew up around Leadville, including Poverty Flats, Slabtown, Finn Town, and Boughtown. The name "Boughtown" referred not only to the many pine trees that grew in the area, but to lodgings the miners built of four posts covered with pine boughs.[7]

In 1893, the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act caused a panic in Leadville and in all of Colorado's silver camps. The price of silver fell rapidly and eventually many of the silver mines closed. Mining companies came to rely increasingly on income from the lead and zinc.[8]

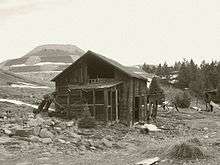

The Sherman Mine produced over 10 million ounces (620,000 pounds; 280,000 kilograms) of silver, mostly between 1968 and 1982, with a value of over $300 million at 2010 prices. Secondary ore minerals from the Sherman mine are popular with mineral collectors.The prominent ruins of the historic buildings and structures of the Hilltop Mine (above the more recent Sherman mine workings) are often visited and photographed by hikers and mountaineers. After 100 years as a major US mining district, the last active mine, the Black Cloud mine, owned by ASARCO, closed in 1999.[9][10] While there is no longer any active mining in the Leadville District, over the course of history more than 2800 patented mine claims were filed and the area contains over 1600 prospects, 1300 shafts, and 155 adits.[11] The value of the cumulative production of silver alone from the Leadville mines is estimated to be $512 million through 1967 (equivalent to about $3.9 billion today).

Geology

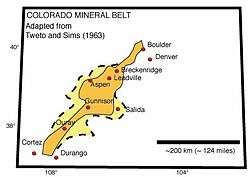

Leadville lies near the center of the Colorado Mineral Belt (CMB), a 50-mile-wide (80 km) strip that runs north and south for 300 miles (480 km). Mineralization of the CMB came primarily by way of intrusions of Tertiary Period magmas. The primary ores of the CMB were generally deposited as mixed metal sulfide mineral veins containing pyrite, galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and gold, silver, and copper. During the last glacial period native gold was freed from the host rock and became available for placer mining.[12] The district is a highly faulted area, intruded with Tertiary quartz monzonite porphyries, on the east side of the Arkansas River graben, part of the Rio Grande Rift system.

The silver occurs associated with manganese and lead in veins, stockworks, and manto-type deposits in the Mississippian Leadville Limestone (here a dolomite), the Devonian Dyer Dolomite, and the Ordovician Manitou Dolomite. Ore minerals are pyrite, sphalerite, and galena, in jasperoid and manganosiderite gangue. In upper levels, the ore minerals are oxidized to cerussite, anglesite, and smithsonite. Leadville was the largest silver-producing district in Colorado. Cumulative production through 1963 was 240 million troy ounces (16 million pounds; 7.5 million kilograms) of silver, three million troy ounces (210 thousand pounds; 93 thousand kilograms) of gold, 987 million tonnes (2.2 trillion pounds; 987 billion kilograms) of lead, 712 million tonnes (1.6 trillion pounds; 712 billion kilograms) of zinc, and 48 million tonnes (110 billion pounds; 48 billion kilograms) of copper.[13]

Geologist R. Mark Maslyn describes the Leadville mining district and the nearby Sherman Mine area saying:

Several mining districts surrounding the central Colorado Sawatch Range contain economic deposits hosted by late Mississippian paleokarst features. These are primarily developed in and along the upper surface of the early Mississippian Leadville Formation. Paleokarst features include isolated eaves and sinkholes as well as integrated cavern systems that are mineralized and can be traced from insurgence to outlet.[14]

Environmental damage related to mining operations

Mining, mineral processing and smelting activities in the area have produced gold, silver, lead and zinc for more than 130 years. Wastes generated during the mining and ore processing activities contained metals such as arsenic and lead at levels posing a threat to human health and the environment. These wastes remained on the land surface and migrated through the environment by washing into streams and leaching contaminants into surface water and groundwater. The site was added to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Priorities List in 1983,. Investigation of the site began in the mid-1980s. Since 1995, EPA and the potentially responsible parties have conducted removal and remedial activities to consolidate, contain and control more than 9,400,000 cubic feet (350,000 cu yd) of contaminated soils, sediments and mine-processing wastes. Cleanups by the potentially responsible parties have involved drainage controls to prevent acid mine runoff, consolidation and capping of mine piles, cleanup of residential properties and reuse of slag. As of September 2011, most of the cleanup had been completed so current risk of exposure is low, although pregnant women, nursing mothers and young children are still encouraged to have their blood-lead levels checked.[15]

Drainage tunnels

As in many mining districts, as the mines extended deeper, keeping the water pumped out of the workings became a major expense. To more economically drain the mines, two tunnels were driven to allow the water to drain by gravity. Water from both tunnels ultimately flows into the Arkansas River.

Yak tunnel

The Yak tunnel, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) long and built between 1895 and 1923 to drain the southern part of the district, has its outlet in California Gulch east of the town of Leadville. The tunnel became part of the California Gulch Superfund site in 1983. In October 1985, a large surge of water from the Yak tunnel reached the Arkansas River, and elevated the dissolved metals content of the river for tens of miles downstream. Water flowing from the tunnel has been treated by its owner, ASARCO, since June 1991, to remove metals.

Leadville tunnel

The Leadville tunnel was started in 1943 by the US Bureau of Mines to drain the mines of the northern part of the district, and so increase metal production. The tunnel has its outlet north of the town of Leadville, on the East Fork of the Arkansas River. In 1959 the US Bureau of Reclamation bought the tunnel for $1.00, as a source of irrigation water.

Since March 1992, the Bureau of Reclamation has treated the water flowing out of the tunnel, to remove dissolved metals and bring the water quality into compliance with the Clean Water Act.

Collapses within the tunnel that began in 1995 partially blocked flow, and have created a large reservoir of an estimated one billion US gallons (3.8 billion litres; 830 million imperial gallons) of water within the tunnel behind the collapse. In February 2008, concerns became public that if the collapse dam should suddenly fail, as has happened in other mine drainage tunnels in Colorado (such as the Yak tunnel, the Argo Tunnel and the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill north of Silverton, Colorado), a large slug of contaminated water would suddenly flow out of the tunnel, overwhelm the treatment facilities, and flow into the Arkansas River. The rise in water level inside the tunnel has caused water with high concentrations of dissolved metals to leak out to the ground surface through springs.[16]

Opinions as to the threat posed varied widely. County Commissioner Mike Hickman said "If it blows, it could be a national catastrophe, not only to Leadville and Lake County but to the entire Arkansas River." On the other hand, Leadville Mayor Bud Elliott stated "This is what happens when you create an emergency when there isn't one."[17] On June 30, 2008, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a report that concluded that a sudden burst of water from the tunnel was unlikely, and that the tunnel posed "no imminent public safety hazard."[18]

On 27 February 2008, the US EPA began pumping 150 US gallons (570 l; 120 imp gal) per minute from the tunnel system, to relieve water pressure upstream from the blockage. The water, pumped from the Gaw mine shaft, was clean enough to discharge to the Arkansas River without treatment.[19] Meanwhile, the EPA drilled a new well into the tunnel system; a pump test was completed in early June 2008 to determine optimal pumping rate.[20]

Tour and visitor attractions

The Mineral Belt National Recreation Trail is an 11.6-mile (18.7 km) all-season biking/walking trail that loops around Leadville and through its historic mining district. In part the trail follows old mining-camp railbeds. Several signs along the way provide historical snippets about Leadville's colorful past.

The "Route of the Silver Kings" is a driving tour of the 20-square-mile (52 km2) historic mining district surrounding Leadville. The tour includes mines, power plants, ghost towns and mining camps.[21]

The National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum occupies 71,000 square feet (6,600 m2). Major exhibits include an elaborate model railroad,[22] a walk-through replica of an underground hardrock mine,[23] the Gold Rush room, with many specimens of native gold,[24] a large collection of mineral specimes,[25] and a mining art gallery.

The Matchless mine and cabin, former home of Baby Doe Tabor, is open as a tourist attraction during the summer.

See also

Gallery of Leadville area minerals

Gold-Quartz

Gold-Quartz Galena—Black Cloud Mine

Galena—Black Cloud Mine Cerussite

Cerussite Smithsonite-Baryte

Smithsonite-Baryte Baryte

Baryte Cerussite-Rosasite-Azurite

Cerussite-Rosasite-Azurite Pyrite

Pyrite Wulfenite-Rosasite

Wulfenite-Rosasite Goethite

Goethite_(17161825282).jpg) Gold - Little Jonny Mine

Gold - Little Jonny Mine

Notes

- Ben H. Parker Jr., Gold Placers of Colorado, Book 2, Colorado School of Mines Quarterly, Oct. 1974, v.69 n.4 p.17.

- Ogden Tweto (1968) Leadville District, Colorado, in Ore Deposits of the United States 1933-1967, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.681-705

- "From the Arkansas River," Rocky Mountain News, 16 May 1860, p.2.

- Mike Flanigan, "Leadville, Cloud City," Denver Post Magazine, 1 Sept. 1985, p.22.

- Ben H. Parker Jr. (1974) Gold Placers of Colorado, book 2, Quarterly of the Colorado School of Mines, v.69, n.4, p.13-19.

- Meyer, August 1851–1905, Parks -georgekessler.org

- http://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/2004/2820/pdf/LeadvilleMapPrint.pdf

- http://geosurvey.state.co.us/minerals/HistoricMiningDistricts/LakeHMD/Leadville/Pages/Leadville.aspx

- Steve Lipsher, "Mine no more," Denver Post, 18 July 1999, p.1B.

- http://www.mininghistoryassociation.org/Leadville.htm

- "Leadville, Colorado". mindat.org. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- Road and Riverside Geology of the Upper Arkansas Valley Part II | Colorado Central Magazine | Colorado news, stories, essays, history and more!

- Ogden Tweto (1968) Leadville District, Colorado, in Ore Deposits of the United States 1933–1967, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.681-705

- http://www.carbonatecreek.com/paleokarst/leadville/leadville.html

- http://www.epa.gov/Region8/superfund/co/calgulch/

- Steve Lipsher, "Feds also fear toxic blowout," Denver Post, 15 Feb. 2008, p.1B.

- Steve Lipsher, "Wading through rhetoric," Denver Post, 25 Feb. 2008, p.1A.

- P. Solomon Banda, "Trapped water in Leadville no threat, feds say," Denver Post, 1 July 2008, p.4B.

- Anne C. Mulkern, "Bills shift Leadville tunnel load to feds," Denver Post, 29 Feb. 2008, p.1B.

- EPA press release (4 June 2008): EPA completes pump test at Leadville Mine Drainage Tunnel

- Route of the Silver Kings (scroll down)

- "National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum - Leadville, Colorado, minerals, gems, history". Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum - Leadville, Colorado, minerals, gems, history". Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum - Leadville, Colorado, minerals, gems, history". Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum - Leadville, Colorado, minerals, gems, history". Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

References

- US Bureau of Reclamation (April 2005): A summary of existing reports which have examined the Leadville mine drainage tunnel (LMDT) discharge to the East Fork of the Arkansas River, Colorado

- US Bureau of Reclamation (15 February 2008): Reclamation partners with Lake County, Colorado and other federal agencies to address public concerns at Leadville mine drainage tunnel

- US Bureau of Reclamation (11 Mar. 2008): Reclamation successfully tests water treatment plant at Leadville Mine Drainage Tunnel

- US Bureau of Reclamation (30 June 2008): Leadville Mine Drainaige Tunnel risk assessment shows residents are safe