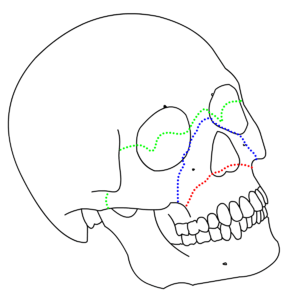

Le Fort fracture of skull

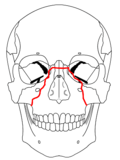

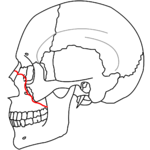

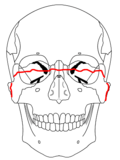

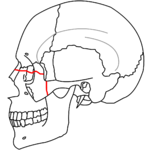

A Le Fort fracture of the skull is a classic transfacial fracture of the midface, involving the maxillary bone and surrounding structures in either a horizontal, pyramidal or transverse direction. The hallmark of Lefort fractures is traumatic pterygomaxillary separation, which signifies fractures between the pterygoid plates, horseshoe shaped bony protuberances which extend from the inferior margin of the maxilla, and the maxillary sinuses. Continuity of this structure is a keystone for stability of the midface, involvement of which impacts surgical management of trauma victims, as it requires fixation to a horizontal bar of the frontal bone. The pterygoid plates lie posterior to the upper dental row, or alveolar ridge, when viewing the face from an anterior view. The fractures are named after French surgeon René Le Fort (1869–1951), who discovered the fracture patterns by examining crush injuries in cadavers.[1]

| Le Fort fracture | |

|---|---|

| |

| Le Fort I (red), II (blue), and III (green) fractures |

Signs and symptoms

Le Fort I — Slight swelling of the upper lip, ecchymosis is present in the buccal sulcus beneath each zygomatic arch, malocclusion, mobility of teeth. Impacted type of fractures may be almost immobile and it is only by grasping the maxillary teeth and applying a little firm pressure that a characteristic grate can be felt which is diagnostic of the fracture. Percussion of upper teeth results in cracked pot sound. Guérin's sign is present characterised by ecchymosis in the region of greater palatine vessels.

Le Fort II and Le Fort III (common) — Gross edema of soft tissue over the middle third of the face, bilateral circumorbital ecchymosis, bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage, epistaxis, CSF rhinorrhoea, dish face deformity, diplopia, enophthalmos, cracked pot sound.

Le Fort II — Step deformity at infraorbital margin, mobile mid face, anesthesia or paresthesia of cheek.

Le Fort III — Tenderness and separation at frontozygomatic suture, lengthening of face, depression of ocular levels (enophthalmos), hooding of eyes, and tilting of occlusal plane, an imaginary curved plane between the edges of the incisors and the tips of the posterior teeth. As a result, there is gagging on the side of injury.[2]

Diagnosis

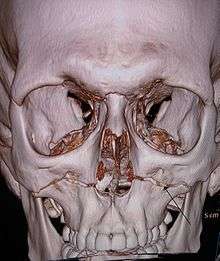

Diagnosis is suspected by physical exam and history, in which, classically, the hard and soft palate of the midface are mobile with respect to the remainder of facial structures. This finding can be inconsistent due to the midfacial bleeding and swelling that typically accompany such injuries, and so confirmation is usually needed by radiograph or CT.[3]

Classification

There are three types of Le Fort fractures. As the classification increases, the anatomic level of the maxillary fracture ascends from inferior to superior with respect to the maxilla:

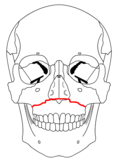

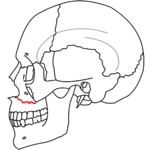

- Le Fort I fracture (horizontal), otherwise known as a floating palate, may result from a force of injury directed low on the maxillary alveolar rim, or upper dental row, in a downward direction. The essential component of these fractures, in addition to pterygoid plate involvement, is involvement of the lateral bony margin of the nasal opening. They also involve the medial and lateral buttresses, or walls, of the maxillary sinus, traveling through the face just above the alveolar ridge of the upper dental row. At the midline, the inferior nasal septum is involved. Historically, it has also been referred to as a Guérin fracture, although this name is less commonly used in practice.

- Le Fort II fracture (pyramidal) may result from a blow to the lower or mid maxillary area. In addition to pterygoid plate disruption, their distinguishing component is involvement of inferior orbital rim. When viewed from the front, the fracture is classically shaped like a pyramid. It extends from the nasal bridge at or below the nasofrontal suture through the superior medial wall of the maxilla, inferolaterally through the lacrimal bones which contain the tear ducts, and inferior orbital floor through or near the infraorbital foramen.

- Le Fort III fracture (transverse), otherwise known as craniofacial dissociation, may follow impact to the nasal bridge or upper maxilla. The salient feature of these fractures, beyond pterygoid plate involvement, is that they invariably involve the zygomatic arch, or cheek bone. These fractures begin at the nasofrontal and frontomaxillary sutures and extend posteriorly along the medial wall of the orbit, through the nasolacrimal groove and ethmoid air cells. The sphenoid is thickened posteriorly, limiting fracture extension into the optic canal. Instead, the fracture continues along the orbital floor and infraorbital fissure, continuing through the lateral orbital wall to the zygomaticofrontal junction and zygomatic arch. Within the nose, the fracture extends through the base of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid air cells, the vomer, which are both part of the nasal septum. As with the other fractures, it also involves the junction of the pterygoids with the maxillary sinuses. CSF rhinorrhea, or leakage of the nutrient laden fluid that bathes the brain, is more commonly seen with these injuries due to ethmoid air cell disruption, as the air cells are located immediately beneath the skull base.[4]

Treatment

Treatment is surgical, and usually is able to be performed once life-threatening injuries are stabilized, to allow the patient to survive the general anesthesia needed for maxillofacial surgery. First a frontal bar is used, which refers to the thickened frontal bone above the frontonasal sutures and the superior orbital rim. The facial bones are suspended from the bar by open reduction and internal fixation with titanium plates and screws, and each fracture is fixed, first at its superior attachment to the bar, then at the inferior attachment to the displaced bone. For stability, the zygomaticofrontal suture is usually replaced first, and the palate and alveolar ridge are usually fixed last. Finally, after the horizontal and vertical maxillary buttresses are stabilized, the orbital fractures are fixed last.[5]

See also

References

- Allsop D, Kennett K (2002). "Skull and facial bone trauma". In Nahum AM, Melvin J (eds.). Accidental injury: Biomechanics and prevention. Berlin: Springer. pp. 254–258. ISBN 0-387-98820-3. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- Lo Casto, A; Priolo, G. D.; Garufi, A; Purpura, P; Salerno, S; La Tona, G; Coppolino, F (2012). "Imaging evaluation of facial complex strut fractures". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 33 (5): 396–409. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2012.06.003. PMID 22964406.

- Kim, S. H.; Lee, S. H.; Cho, P. D. (2012). "Analysis of 809 facial bone fractures in a pediatric and adolescent population". Archives of Plastic Surgery. 39 (6): 606–11. doi:10.5999/aps.2012.39.6.606. PMC 3518003. PMID 23233885.

- Winegar, B. A.; Murillo, H; Tantiwongkosi, B (2013). "Spectrum of critical imaging findings in complex facial skeletal trauma". RadioGraphics. 33 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1148/rg.331125080. PMID 23322824.

- Chung, K. J.; Kim, Y. H.; Kim, T. G.; Lee, J. H.; Lim, J. H. (2013). "Treatment of complex facial fractures: Clinical experience of different timing and order". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 24 (1): 216–20. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318267b6f7. PMID 23348288.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fractures of the human maxilla. |