Largehead hairtail

The largehead hairtail (Trichiurus lepturus) or beltfish is a member of the cutlassfish family, Trichiuridae. This common to abundant species is found in tropical and temperate oceans throughout the world.[1][2] The taxonomy is not fully resolved, and the Atlantic, East Pacific and Northwest Pacific populations are also known as Atlantic cutlassfish, Pacific cutlassfish and Japanese cutlassfish, respectively. This predatory, elongated fish supports major fisheries.[3]

| Largehead hairtail | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Trichiuridae |

| Genus: | Trichiurus |

| Species: | T. lepturus |

| Binomial name | |

| Trichiurus lepturus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Appearance

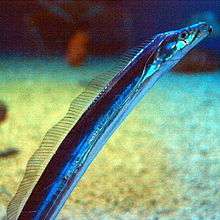

Largehead hairtails are silvery steel blue in color, turning silvery gray after death.[3] The fins are generally semi-transparent and may have a yellowish tinge.[3] Largehead hairtails are elongated in shape with a thin pointed tail (they lack a fish tail in the usual form). The eyes are large, and the large mouth contains long pointed fang-like teeth.[3]

Largehead hairtails grow to 6 kg (13 lb) in weight,[4] and 2.34 m (7.7 ft) in length.[2] Most are only 0.5–1 m (1.6–3.3 ft) long,[3] although they regularly reach 1.5–1.8 m (4.9–5.9 ft) in Australia.[4]

Range and habitat

Largehead hairtails are found worldwide in tropical and temperate oceans.[2] In the East Atlantic they range from southern United Kingdom to South Africa, including the Mediterranean Sea.[1][5] In the West Atlantic it ranges from Virginia (occasionally Cape Cod) to northern Argentina, including the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico.[1][6] In the East Pacific they range from southern California to Peru.[1] Widespread in the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the Red Sea to South Africa, Japan, the entire coast of Australia (except Tasmania and Victoria) and Fiji, they are absent from the central Pacific Ocean, including Hawaii.[1][3][7] Some populations are migratory.[3]

A study of largehead hairtails in southern Japan's Bungo Channel indicated that the optimum water temperature is 20–24 °C (68–75 °F).[8] Based on fishing catches in the Jeju Strait of South Korea, the species resides mainly in water warmer than 14 °C (57 °F), while catches are poor in colder water.[9] Off southern Brazil it mainly occurs in waters warmer than 16 °C (61 °F).[10] It is absent from waters below 10 °C (50 °F).[1] The largehead hairtail prefers relatively shallow coastal regions over muddy bottoms,[1] but it sometimes enters estuaries and has been recorded at depths of 0 to 589 m (0–1,932 ft).[2] In European waters, most records are from 100 to 350 m (330–1,150 ft),[5] Off southern Brazil hairtails are most abundant between 40 and 120 m (130–390 ft),[10] they have been recorded between 55 and 385 m (180–1,263 ft) in the East Pacific,[3] and in southern Japan's Bungo Channel they are primarily known from 60 to 280 m (200–920 ft) but most common between 70 and 160 m (230–520 ft).[8] They are mainly benthopelagic, but may appear at the surface during the night.[1]

Taxonomy

Although often considered a single highly widespread species,[2] it has been argued that it is a species complex that includes several species with the main groups being in the Atlantic (Atlantic cutlassfish), East Pacific (Pacific cutlassfish), Northwest Pacific (Japanese cutlassfish) and Indo-Pacific. If split, the Atlantic would retain the scientific name T. lepturus, as the type locality is off South Carolina. The Northwest Pacific (Sea of Japan and East China Sea) differs in morphometrics, meristics and genetics, and is sometimes recognized as T. japonicus.[11][12] Morphometric and meristic differences have also been shown in the population of the East Pacific (California to Peru), leading some to recognize it as T. nitens.[13] Neither T. japonicus nor T. nitens are recognized as separate species by FishBase where considered synonyms of T. lepturus,[2] but they are recognized as separate species by the Catalog of Fishes.[14] The IUCN recognizes the East Atlantic population as a distinct, currently undescribed species.[1] This is based on genetic evidence showing a divergence between West and East Atlantic populations.[1] However, this would require that T. japonicus, T. nitens and the Indo-Pacific populations also are recognized as separate species, effectively limiting T. lepturus to the West Atlantic (contrary to IUCN[1]), as they all show a greater divergence.[15]

Additional studies are required on the possible separation and nomenclature of the Indo-Pacific populations. Based on studies of mtDNA, which however lacked any samples from the southern parts of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, there are three species in the Indo-Pacific: T. japonicus (marginal in the region, see range above), T. lepturus (West Pacific and Eastern Indian Ocean; the species also found in the Atlantic) and the final preliminarily referred to as Trichiurus sp. 2 (Indian Ocean, and East and South China Seas).[15][16] It is likely that Trichiurus sp. 2 equals T. nanhaiensis.[17] The names T. coxii and T. haumela have been used for the populations off Australia and in the Indo-Pacific, respectively, but firm evidence supporting their validity as species is lacking.[12][15]

Behavior and life cycle

Juveniles participate in the diel vertical migration, rising to feed on krill and small fish during the night and returning to the sea bed in the day. This movement pattern is reversed by large adults, which mainly feed on fish.[2][3] Other known prey items include squid and shrimp, and the highly carnivorous adults regularly cannibalise younger individuals.[18] Largehead hairtails are often found in large, dense schools.[7][19]

Spawning depends on temperature as the larvae prefer water warmer than 21 °C (70 °F) and are entirely absent at less than 16 °C (61 °F). Consequently, spawning is year-round in tropical regions, but generally in the spring and summer in colder regions.[20] Through a spawning season each female lays many thousand pelagic eggs that hatch after three to six days.[3] In the Sea of Japan most individuals reach maturity when two years old, but some already after one year.[3] The oldest recorded age is 15 years.[2]

Fisheries and usage

Largehead hairtail is a major commercial species. With reported landings of more than 1.3 million tonnes in 2009, it was the sixth most important captured fish species.[21] The species is caught throughout much of its range, typically by bottom trawls or beach seines, but also using a wide range of other methods.[1] In 2009, by far the largest catches (1.2 million tonnes) were reported by China and Taiwan from the Northwest Pacific (FAO Fishing Area 61). The next largest catches were reported from South Korea, Japan, and Pakistan.[21] Some of the numerous other countries where regularly caught include Angola, Nigeria, Senegal, Mauritania, Morocco, Brazil, Trinidad, Colombia, Mexico, southeastern United States, Iran,[1] India,[19] and Australia.[4]

In Korea, the largehead hairtail is called galchi (갈치), in which gal (갈) came from Middle Korean galh (갏) meaning "sword" and -chi (치) is a suffix for "fish".[22][23][24][25] It is popular for frying or grilling. In Japan, where it is known as tachiuo ("太刀 (tachi)": sword, "魚 (uo)":fish), they are fished for food and eaten grilled or raw, as sashimi. They are also called "sword-fish" in Portugal and Brazil (peixe-espada), where they are eaten grilled or fried. Its flesh is firm yet tender when cooked, with a moderate level of "fishiness" to the smell and a low level of oiliness. The largehead hairtail is also notable for being fairly easy to debone.

- Largehead hairtails at a fish market in Tokyo

Galchi-gui (grilled largehead hairtail)

Galchi-gui (grilled largehead hairtail) Galchi-hoe (raw largehead hairtail)

Galchi-hoe (raw largehead hairtail) Galchi-jorim (simmered largehead hairtail)

Galchi-jorim (simmered largehead hairtail)

References

- Collette, B.B.; Pina Amargos, F.; Smith-Vaniz, W.F.; et al. (2015). "Trichiurus lepturus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T190090A115307118. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T190090A19929379.en.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Trichiurus lepturus" in FishBase. February 2015 version.

- "Trichiurus lepturus". FAO. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Prokop, F.B. (2006). Australian Fish Guide (3rd ed.). p. 100. ISBN 978-1865131078.

- Muus, B.; J. G. Nielsen; P. Dahlstrom & B. Nystrom (1999). Sea Fish. p. 234. ISBN 978-8790787004.

- Kells, V. & K. Carpenter (2011). A Field Guide to Coastal Fishes from Maine to Texas. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8018-9838-9.

- Hutchins, B. & R. Swainston (1996). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-86252-661-7.

- Kao; Tomiyasu; Takahashi; Ogawa; Hirose; Kurosaka; Tsuru; Sanada; Minami & Miyashita (2015). "Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Hairtail (Trichiurus japonicus) in the Bungo Channel, Japan". The Journal of the Marine Acoustics Society of Japan. 42 (4): 167–176. doi:10.3135/jmasj.42.167.

- Kim, S.-H. & H.-K. Rho (1998). "Study on the Assembling Mechanism of the Hairtail, Trichiurus lepturus, at the Fishing Grounds of the Cheju Strait". Journal of the Korean Society of Fisheries Technology. 34 (2): 134–177.

- Martins, A.G.; Haimovici, M. (1997). "Distribution, abundance and biological interactions of the cutlassfish Trichiurus lepturus in the southern Brazil subtropical convergence ecosystem". Fisheries Research. 30 (3): 217–227. doi:10.1016/s0165-7836(96)00566-8.

- Chakraborty, A.; Aranishi, F.; Iwatsuki, Y. (2006). "Genetic differentiation of Trichiurus japonicus and T. lepturus (Perciformes: Trichiuridae) based on mitochondrial DNA analysis" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 45 (3): 419–427.

- Tzeng, C.H.; Chen, C.S.; Chiu, T.S. (2007). "Analysis of morphometry and mitochondrial DNA sequences from two Trichiurus species in waters of the western North Pacific: taxonomic assessment and population structure". Journal of Fish Biology. 70: 165–176. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01368.x.

- Burhanuddin, A.I.; Parin, N.V. (2008). "Redescription of the trichiurid fish, Trichiurus nitens Garman, 1899, being a valid of species distinct from T. lepturus Linnaeus, 1758 (Perciformes: Trichiuridae)". Journal of Ichthyology. 48 (10): 825. doi:10.1134/S0032945208100019.

- Eschmeyer, W.N.; Fricke, R.; van der Laan, R. (31 August 2017). "Trichiurus". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Hsu, K.C.; Shih, N.S.; Ni, I.H.; Shao, K.T. (2009). "Speciation and population structure of three Trichiurus species based on mitochondrial DNA" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 48 (6): 835–849.

- Firawati, I.; M. Murwantoko & E. Setyobudi (2016). "Morphological and molecular characterization of hairtail (Trichiurus spp.) from the Indian Ocean, southern coast of East Java, Indonesia". Biodiversitas. 18 (1): 190–196. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d180126.

- Shih, N.T.; K.C. Hsu & I.H. Ni (2011). "Age, growth and reproduction of cutlassfishes Trichiurus spp. in the southern East China Sea". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 27 (6): 1307–1315. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2011.01805.x.

- Bittar; Awabdi; Tonini; Vidal Junior; Madeira Di Beneditto (2012). "Feeding preference of adult females of ribbonfish Trichiurus lepturus through prey proximate-composition and caloric values". Neotrop. Ichthyol. 10 (1): 197. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252012000100019.

- Rajesh; Rohit; Vase; Sampathkumur & Sahib (2014). "Fishery, reproductive biology and stock status of the largehead hairtail Trichiurus lepturus Linnaeus, 1758 off Karnataka, south-west coast of India". Indian J. Fish. 62 (3): 28–34.

- Martins, A.G.; Haimovici, M. (2000). "Reproduction of the cutlassfish Trichiurus lepturus in the southern Brazil subtropical convergence ecosystem" (PDF). Scientia Marina. 64 (1): 97–105. doi:10.3989/scimar.2000.64n197.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2011). Yearbook of fishery and aquaculture statistics 2009. Capture production (PDF). Rome: FAO. pp. 27, 202–203.

- "galchi" 갈치. Standard Korean Language Dictionary (in Korean). National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Sin, Ihaeng; Gim, Gyeongjun; Gim, Jinam (1960). Yeogeo yuhae 역어유해(譯語類解) [Categorical Analysis of the Chinese Language Translation] (in Korean). Joseon Kora: Sayeogwon.

- "galh" 갏. Standard Korean Language Dictionary (in Korean). National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- 홍, 윤표 (1 September 2006). ‘가물치’와 ‘붕어’의 어원. National Institute of Korean Language (in Korean). Retrieved 4 June 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trichiurus lepturus. |

- "Trichiurus lepturus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 March 2006.