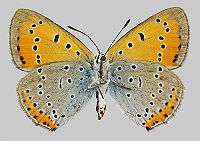

Large copper

The large copper (Lycaena dispar) is a butterfly of the family Lycaenidae. L. dispar has been commonly arranged into three subspecies: L. dispar dispar, (single-brooded) which was commonly found in England, but is now extinct, L. d. batavus, (single-brooded) can be found in the Netherlands and has been reintroduced into the United Kingdom, and lastly, L. d. rutilus, (double-brooded) which is widespread across central and southern Europe.[2] The latter has been declining in many European countries, due to habitat loss.[1] Currently L. dispar is in severe decline in northwest Europe, but expanding in central and northern Europe.[3]

| Large copper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Mounted | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. dispar |

| Binomial name | |

| Lycaena dispar (Haworth, 1802) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Native to

Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Poland, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.[1]

It is regionally extinct in the United Kingdom, due to habitat loss.[1] As well it has been extinct in the British Isles, since the 1860s, with declining numbers occurring across numerous, other western European countries.[2]

Subspecies

- L. d. dispar (Haworth, 1802) − England − extinct

- L. d. batava (Oberthür, 1923) – Netherlands

- L. d. rutila (Werneberg, 1864) − Europe, Caucasus, Transcaucasia, N. Tien-Shan, W. Tien-Shan, Dzhungarsky Alatau, Ghissar

- L. d. festiva Krulikowsky, 1909 − Ural, W. Siberia

- L. d. dahurica (Graeser, 1888) − Transbaikalia, W.Amur

- L. d. aurata Leech, 1887 − Siberia, E. Amur, Ussuri.

Subspecies Lycaena dispar batava

The subspecies Lycaena dispar batava is only found in marshy areas in North West Overijssel (the areas Weerribben and Wieden) in the Netherlands. Furthermore, it only feeds on Rumex hydrolapathum, making it a vulnerable subspecies. To protect the subspecies, there is a conservation plan, mainly aimed at expanding its habitat.

History

Various species of Lepidoptera are described across Europe. Lycaena dispar was first recorded in 1749, from the Huntingdonshire fens,[4] England.[5] Documentation of the large copper was done by the Committee appointed by the Entomological Society of London for the Protection of British Lepidoptera.[5]

Reintroduction

Britain first attempted to reintroduce L. dispar in 1901, when G.H. Verbal released a number of caterpillars in Wicken Fen; however, due to a lack of host plants, the reintroduction was not viable.[5] The first successful reintroduction of the species came in 1913, when W.B. Purefoy, established a colony of L. d. rutilus in Greenfields, Tipperary, a small bog made suitable for L. dispar through the planting of preferred food plants.[5]

In 1915, L. d. batavus was described in the Netherlands, despite being almost indistinguishable from extinct L. d. dispar. [5] L. d. batavus populations in Britain, occurred in the fenland area around Whittlesea Mere, extending to Yaxley and Holme Fens, all are characterized by acidic peat bogs, however this population is currently extant.[5]

Distribution

L. dispar, is widely distributed in central Europe, as far north as southern Finland, extending across temperate Asia to the Amur region and to Manchuria Korea.[2][1] Occurring throughout much of mainland Europe, L. dispar, is found between 40° and 60° latitudes.[2]

Central Europe

In central Europe L. dispar commonly inhabits drier areas, such as fallows and urban wetlands.[2]

Estonia

L. dispar is one of the newer lepidopteran fauna in Estonia.[2] It was absent from the area up until the 20th century, when it was recorded in 1947, close to the town of Tartu, in the eastern part of Estonia.[2] Over Recent decades the species has remained absent on the islands off the Estonian western coast, scarce in the western regions, and has been expanding into the northwestern part of the country.[2] L. dispar, has been considered univoltine, in Estonia, with a flight time between the end of June and to the end of July.[2] In Estonia the butterfly has two primary host plants, R. crispus and R. obtusifolius.[2] Notably, L. dispar has been considered an expansive species, in Estonia, with the acquired status of a widespread butterfly. As a result, L. dispar is not restricted by habitat requirements, as is common in other populations of L. dispar across Europe.[2]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands populations of L. dispar appear to be more monophagous on R. hydrolapathum.[2]

Germany and Austria

L. dispar is characteristically oligophagous on various Rumex species.[2]

England, Ireland and the Netherlands

The British subspecies of this butterfly (L. d. dispar) has been extinct since 1864. Most of our knowledge of its life cycle and ecology comes from studies of the similar subspecies (L. d. batava') found in the Netherlands. The species can be identified by the silvery hindwing undersides, from the large specimens of the related, more common, drier habitat species Caena virgaureae and Lycaena hippothoe.

Habitat

L. dispar is a wetland species in decline throughout Europe.[6] The primary habitat of this butterfly has been drained for agricultural and other land usage, limiting their habitat.[6] When it can, L. dispar will utilize plants growing away from watersides and among reed-fen vegetation.[7] In this way L. dispar can avoid possible flooding that can occur in lower lying areas closer to the water's edge.[6] The species prefers undisturbed grasslands along the riverbanks and stream banks, where its larval food plant, the greater water dock, (R. hydrolapathum) can be found.[3]

Warmer microclimates, as well as warmer regions in general are preferred by L. dispar, allowing for faster growth time of larvae.[3]

Land disturbances through agriculture, primarily the mowing of grass, and other foliage has a negative influence on populations of L. dispar, such that mowing shortly after egg-laying, will result in disastrous losses due to the eggs being destroyed and the newly hatched larvae being deprived of host plants, for food: L. dispar lays its eggs on host food plants, commonly low-lying, with larval migration limited to the area around their birth, host plant.[3] For conservation purposes, it is highly recommended that L. dispar habitats be closely managed, with promotion in increased habitat heterogeneity, being most important: this strategy has proven beneficial for many other species of butterfly.[3]

Host plants

The greater water dock, (Rumex) is host plant of L. dispar, with a broad range of species in the Eastern part of its distribution, and a more limited range of species in its Western distribution.[3] Plant specifications, such as height, size, phonological stages (increase in variables is preferable) and nutrition, as L. dispar is sensitive to its host plants acidity, are all conditions that are taken into consideration when a females chooses host plants to lay her eggs on: these plant will also provide emerging larvae with a source of food.[3]

Favourable host plants include R. cripus, the preferred food plant in southwest Germany and Austria,[2] R. obtusifolius, being the preferred food plant in Southwest France, R. patientia, and the lesser common R. hydrolapathum, which is the main food plant in the butterflies northwestern range (Poland and North Germany[2]), where decline in populations has been most severe, and R. stenophyllus.[3] Other commonly distributed Rumex species, that are used by L. dispar are: R. obtusifolius, R. conglomeratus, R. sanguineus, R. aquaticus, R. patientia, and R. stenophyllus.[2] The sorrels, the Rumex species containing oxalic acid, Rumex acetosa, have less commonly been reported as host plants for L. dispar.[2]

Life cycle

L. dispar has a bivoltine life cycle, throughout most of its European distribution, stretching from May to June, and from the end of July to early September, with peak flight occurring in July.[2] Two generations of L. dispar are standard, the first is characterized by fewer numbers, with the second generation producing more offspring that overwinter, as half-grown, third instar larvae.[2][7] In the warmer parts (southern distribution) of its European habitat range, L. dispar can be capable of third generations.[2] During the winter months, larvae enter diapause, a period of metabolic inactivity, that is characterized by the development of physiological tolerance to various environmental stressors: cold temperatures, starvation, in order to survive winter conditions.[7] Overwinter survival can be greatly reduced due to flooding for prolonged periods of time, resulting in high mortality of L. dispar larvae in diapause.[6]

L. dispar larvae have three characteristic stages: pre-diapause in the autumn, winter diapause and post-diapause in the spring.[6] Heavy mortality is common between oviposition (when females lay their eggs) in the late summer and the resumption of larval feeding in late spring: larvae begin feeding again in early may.[6] In order to enter diapause, L. dispar uses temperature and photoperiodic indicators to determine when to start the overwinter process: entering diapause at low temperatures (<15°C) [7] As well as temperature, environmental and endogenous factors also determine when larvae terminate diapause: generally when ambient temperature is high (>25°C).[7][7]

Females

L. dispar females are capable of producing on average 32 chorionated eggs per egg load with an average of 714 eggs being laid in their lifetime.[8] Ovipositing females are specific about the quality of host plant they chose to lay their larvae on with plants preferably lacking flowering or fruiting stems and having inflorescences.[3] Plants that receive greater sunlight allow for larvae to grow faster and develop within a shorter period. Females, for this reason prefer warmer microclimates where host plant conditions are optimal.[7] Notably herbivore leaf damage and fungal infections of host plants, are not significant in reducing egg densities, laid by females.[7] In late June, the L. dispar larvae leave their host, food plant, migrating to vegetation no further than 25cm away from their original host and roughly 10cm above ground.[8] Once there larvae begin to change color, from bright green to pale yellow-brown, allowing them to blend in better with their surroundings during pupation, which lasts between 10 to 14 days.[8][7]

Predation

L. dispar is subject to predation from invertebrate species as well as parasitoids (Phryxe vulgaris).[6] During pre-diapause invertebrate predation is responsible for a large proportion of mortality.[6] Parasitoids are commonly found in post-diapause larvae, and results in the death of late, instar larvae.[6] Vertebrate predators often include reed-nesting birds amphibians and small mammals.[6]

Conservation

This species was formerly classified as a priority for protection and re-introduction in the UK under its national Biodiversity Action Plan. The species was driven to extinction in Britain by drainage and consequently great reduction of fen habitat. In the rest of the Western Europe, the draining of wetlands and building and agricultural activity on shallow riverbanks has caused a strong decline. In eastern Europe, undeveloped riverbanks and deltas are a habitat for the species, though even there it is somewhat threatened due increasing human influence on these areas.

There have been several reintroduction attempts to sites in both Britain and Ireland, but these have all ultimately failed. This is largely due to L. dispar stock being raised in captivity for long periods of time, before being released into the wild, resulting in adults that are maladapted to their natural environment, and ultimately do not survive.[6] Research is now being conducted to see whether a further attempt is worthwhile in more extensive habitats available in the Great Fen project and the Norfolk Broads.

Today, L. dispar is a near threatened species in some regions, leading to a growing concern over its conservation.[7] It is listed in the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, and is protected via Annexes II and IV of the European Community Habitats Directive.[2] In order to boost population numbers, mass rearing would be beneficial, therefore further research is needed to improve survivorship of mass-reared, L. dispar individuals.[7] Conservation efforts need to address the species' high sensitivity to climate and land usage, such as reclamation of wetlands for agricultural purposes and intensive management of grasslands through mowing of vegetation, having a negative influences on population numbers of L. dispar.[2]

References

- Gimenez Dixon, M. (1996). "Lycaena dispar". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T12433A3347854. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T12433A3347854.en.

- Lindman, Ly; Remm, Jaanus; Saksing, Kristiina; Sõber, Virve; Õunap, Erki; Tammaru, Toomas; Leather, Simon R.; DeVries, Phil (2015). "Lycaena dispar on its northern distribution limit: an expansive generalist". Insect Conservation and Diversity. 8: 3–16. doi:10.1111/icad.12087.

- Strausz, Martin; Fiedler, Konrad; Franzén, Markus; Wiemers, Martin (2012). "Habitat and host plant use of the Large Copper Butterfly Lycaena dispar in an urban environment". Journal of Insect Conservation. 16 (5): 709–721. doi:10.1007/s10841-012-9456-5.

- "Huntingdonshire".

- Duffey, Eric (1968). "Ecological studies on the large copper butterfly Lycaena dispar Haw. batavus Obth. at Woodwalton Fen National Nature Reserve, Huntingdonshire". Journal of Applied Ecology. 5 (1): 69–96. doi:10.2307/2401275. JSTOR 2401275.

- Webb, Mark R.; Pullin, Andrew S. (1996). "Larval survival in populations of the large copper butterfly Lycaena dispar batavus". Ecography. 19 (3): 279–286. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1996.tb00237.x. JSTOR 3682914.

- Kim, Seong-Hyun; Kim, Nam Jung; Hong, Seong-Jin; Lee, Young-Bo; Park, Hae-Chul; Je, Yeon-Ho; Lee, Kwang Pum (2014). "Environmental induction of larval diapause and life-history consequences of post-diapause development in the Large Copper butterfly, Lycaena dispar (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)". Journal of Insect Conservation. 18 (4): 693–700. doi:10.1007/s10841-014-9678-9.

- Bink, F. A. (1986). "Acid stress in Rumex hydrolapathum (Polygonaceae) and its influence on the phytophage Lycaena dispar (Lepidoptera; Lycaenidae)". Oecologia. 70 (3): 447–451. Bibcode:1986Oecol..70..447B. doi:10.1007/bf00379510. JSTOR 4218073.