Lands of Doura

The Lands of Doura,[1] Dawra,[2] Dawray,[3] Dowrey[4] Dowray,[5]Dourey[6] or Douray[7] formed a small estate, at one time part of the Barony of Corsehill and Doura, situated near the Eglinton Estate in the Parish of Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland.

| Lands of Doura | |

|---|---|

| Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland UK grid reference NS3578151453 | |

Lands of Doura | |

| Coordinates | 55.6495°N 4.6317°W |

| Grid reference | NS 34497 42702 |

| Type | Manor House |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Controlled by | Clan Cunninghame |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Demolished |

| Site history | |

| Built | 17th century |

| Built by | Cuninghame family |

| Materials | Stone |

Doura Hall and estate

Pont notes that 'Dowra' or variants on this spelling is a name found in several places in Ayrshire.

In 1361 the lands of Doura were held by Sir Hugh de Eglinton of Eglinton. Upon Sir Hugh's death they passed to Montgomerie of Eagleshame following his marriage to the only heir of Sir Hugh.[8]

In 1482 Doura was linked with Armsheugh and Patterton as a possession of Lord Boyd, being part of the lands once held by his mother, Princess Mary, sister of King James III.[8]

Doura Hall was a 17th-century building located on the road up to Doura Mains farm. It had been the intention of the Lairds of Corsehill to build a new house at the 'Dowrie' in the Barony of Dowra, however nothing was done, but plans of the proposed buildings have survived.[9] James Boswell described Doura as a poor building having visited the hall to see his niece Annie Cuningham.[10] It was demolished in the 19th century and appeared on the 1910 25-inch (640 mm) to the mile OS map. A Dovecote hill and orchard brae are further reminders of this estate, owned by the Cuninghames of Corsehill.[9] A smithy was located at the Doura hamlet in the late 18th century.

In 1691 the Hearth Tax records show that the hall had six hearths and was occupied by Lady Corsehill. The barony had sixteen other dwellings.[11]

Roy's map of 1747-55 shows an orchard, two main buildings and enclosures within a rectangular site.[12]

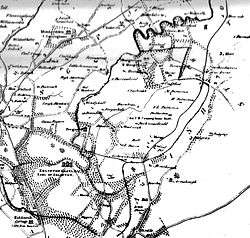

In 1775 Andrew Armstrong's, A new map of Ayrshire... shows the 'Dowrey' mansion house and wooded policies of Doura. John Ainslie's 1821 Map of the Southern Part of Scotland uses the name 'Dourey'.

In 1856 'The Hall' is shown as a ruin with several buildings associated with it.[13] South Millburn Farm is shown as East Doura on Aitken's map of 1823.

The name 'Doura' its variants may be a contraction of 'Dollywraa', the 'enclosure of the Doleland'. This Dole land refers to land that is jointly owned where each owner or user has an assigned portion that is designated by the presence of distinct landmarks[14]

The Barony Court

In April 1669 Alexander Cuninghame of Corsehill held the Corsehill Baron-Court at the 'Place of Dawray' with David Dickie as his baillie.[3] One of the cases tried was that of a coal miner, Thomas Miller, and a smith at Balgray Mill, Hew Dyat. Hew had thrown a stone into Thomas's face and the outcome was that Hew apologised to all concerned and not only paid a fine but also paid for the treatment of Hew's wounds.[15] The tenants were also warned to pay their rents on time.[15] The surnames of the jurymen were Adame, Ker, Miller, Frow, Broune, Hogstoun, Walker, Patoun and Garvane.[3]

The December 1709 court of the Lands and Barony of Corsehill includes the lands of Dowray after a break of forty years and the requirement to pay rents to David Boyle, Earl of Glasgow.[5] In June 1710 the tenants of Douray are warned by the court not to shoot hares, doves, and partridges, burn the moors, poach salmon and trout out of season. Also to not to cut 'greenwood', steep green lint in running water, etc.[16]

Doura Mains Farm

Dura Mains Farm (55.6512 -4.6323) is first recorded on a map in 1832.[1] Doura Hall lay to the left of the driveway leading up to the farm. The farm was still present in 2013.

The lairds

Andrew Cuninghame, second son of William Cuninghame, 4th Earl of Glencairn, was the first of the House of Corsehill in 1532[17] and in 1532 his father had granted to him the lands of Doura, Potterton. The property of Dowra and Patterton therefore formed part of the Barony of Corsehill, held since the 16th century by the ancestors of the Montgomerie Cuninghames of Corsehill, Baronets who held the remaining parts of the barony lands in the 19th century.[18] The clan name has many variations and the spelling used here is 'Cuninghame'.

In 1551/2 John Docheon, in 1544 one of the remaining seventeen monks of Kilwinning Abbey, signed a charter to his namesake granting him lands at Doura.[19] In 1611 Gilbert Docheon of Doura was owed money by David Montgomery, a resident of Ireland.[20]

Cuthbert Cuninghame inherited the barony from William Cuninghame and married Maud Cuninghame of Aiket Castle. He had two sons, Alexander and Patrick, the latter being involved in the murder of Hugh, Earl of Eglinton.[17] Patrick was murdered in revenge by the Montgomeries.[21]

The 4th Laird, Sir Walter Montgomerie-Cuninghame, lived at Doura in the 1780s after the family ran into financial difficulties due to the American War of Independence and lost possession of Lainshaw House and estate.[9]

In 1816 Sir James Cuninghame was assessed to pay £22 10s 0d towards the rebuilding of the tower at Kilwinning Abbey. The amount concerned relates to the value of the estate at the time and was second only to the Earl og Eglinton.[22]

In 1870 the MP, Sir William James Montgomerie-Cuninghame succeeded his father Thomas in the properties of Corsehill and Kirktonholme that included Doura.[18] The family now live in England.

Doura Village

The Annick Lodge school served the village and the local farming community of Armsheugh and Auchenwinsey.[23] The miner's rows have been demolished.[23] In 1856 a village with a smithy existed at Doura with Dovecothill located at the entrance to 'The Hall'. A row of cottages recorded as 'Winniebrae' existed nearby with a number of old pits marked.[13] In 1895 the Winniebrae Row was abandoned and the row at Laigh Doura was likewise abandoned, however the brick and tile works was still active and the local mines with rail links were still present.[24] The village lay on the main Loch Libo Road and had a population of 350 in the 19th century.[25]

Industry

Dobie records that the quality of Doura coal was for many years very well respected and that the miners' village associated with the pits had 350 inhabitants.[18]

In the late 18th century twelve to sixteen miners were employed at Doura and John Galt describes how the coal waggons ran down to the town through the Glasgow Vennel, a charge of 1d per cart being levied and more if the coal was taken to the shore for export to Ireland.[26]

Dr. Duguid states in the late 18th century that the Doura pits had not been worked since the time of Mary Queen of Scots (1542–1587), when they had supplied coal to the Palace of Holyrood and Edinburgh Castle.[27] This is not as unlikely as it seems because the mining methods of the time had exhausted the available coal stocks and that their existed an "exhorbitant dearth and scantness of fewale within the Realme."[28] He was the doctor for the pit and recalls that when the pit was drained, William Ralston, the ganger, found the old workmen's tools and their bones at the coal face.

In Duguid's time another disaster took place after heavy frosts had loosened the pit soil and the pit supports gave way. Pate Brogildy from the Redboiler survived, however he later had his arm ripped off at the shoulder blade by the flywheel of the pit steam engine. He survived as the twisting motion of the 'amputation' had sealed the arteries. Willie Forgisal (Fergushill?) of Torranyard had his leg amputated above the knee. James Jamphrey from Corsehill was killed instantly.[29]

The Statistical Account records that the coals at Doura were ell and stone-coals. Easter Doura mine employed 12 - 16 colliers and was owned by Lord Lisle and was leased by him for £140 per annum in the 18th century.

The old orchard at Doura Hall was recalled in the names of several coal and fireclay pits and a stone quarry that closed in the late 19th or early 20th centuries.[30]

A brick and tile works was located at Doura in 1895[24][31] and by 1908 a fireclay works is recorded.[32]

The Doura Branch railway

The Ardrossan and Johnstone Railway was originally a horse drawn waggonway which opened in 1831 between Ardrossan and Kilwinning.[33] It was built to the Scotch gauge of 4 ft 6 in (1,372 mm) and was worked by horses.[34] The 3-mile (4.8 km) long Doura branch was opened in 1834, left the main line near Stevenston and crossed under the Glasgow, Paisley, Kilmarnock and Ayr Railway to reach the Doura coal pit.[35][36] The 0.5-mile (0.80 km) Fergus Hill branch left the Doura branch just after the Lugton Water crossing to reach the Fergus Hill coal pit.[35][36]

In 1833 (sic) Sir James Cunningham extended the Doura branch to his coal and fireclay workings at Perceton. Up until the 1850s this line was worked using horse haulage, each waggon carrying about a ton of coal. The Doura branch was private until 1839 when the Ardrossan Railway Company came into being.[37] The relaying of track with a heavier rail suitable for steam locomotives and the gauge conversion from 4 ft 6ins to 4 ft 8½ins took place in Spring 1840, however the track to the coal pits below Patterton Farm was not converted and seems to have been lifted due to the closure of the mines it had served.

A Standard Gauge railway ran down to the collieries at 'low' Doura via a junction on the line to Perceton, and served the fireclay, brickworks and tileworks in this area as shown by 19th century and early 20th century OS maps.

Micro-history

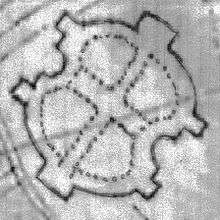

Benslie Wood is a very unusual landscape feature of some considerable size, originally laid out as a bilaterally symmetrical design near Benslie village as shown on the 1750s Roy's map. It lies outside the ornamental woodlands of the old Eglinton 'Pleasure Gardens' and has the appearance of the foundations of a very large building, although it was made up of trees with a raised bank delineating its boundaries which may have carried a pale or fence at one time. The feature remains largely intact on three sides.55°39′0.8″N 4°38′37.7″W

In 1901 the coal pits at Doura were a good source of Carboniferous fossils.[38]

See also

- Benslie

- Eglinton Castle

- Montgomery-Cuninghame baronets

- The Lands of Montgreenan

References

- Notes

- Thomson's Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- Blaeu Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- A&HC, Page 86

- Armstrong's Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- A&HC, Page 242

- Ainslie Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- A&HC, Page 210

- Paterson, Page 272

- Davis, pages 206 & 207.

- Boswell, Page 100

- Urquhart, Page 92

- Roy's Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- 25 Map of 1856 Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- Place Names of Fife and Kinross Retrieved : 2013-05-26

- A&HC, Page 87

- A&HC, Page 244

- Paterson, Page 590

- Dobie, Page 131

- Sanderson, Page 115

- Sanderson, Page 123

- Dobie, Page 132

- Ker, Page 184

- Love (2003), Page 55

- 25 inch Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- McMichael, Page 169

- McJannet, Page 259

- Service, page 117.

- Hall, Page 29

- Service, pages 138–139.

- Mines Department, Page 32

- Bricks Retrieved : 2013-05-23

- 6 inch Map Retrieved : 2013-05-24

- Lewin, pages 17–18

- Whishaw

- Lewin.

- Whishaw.

- Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park

- Scott Elliot, Page 561

- Sources

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to the counties of Ayrshire & Wigtown. Edinburgh : Ayr Wig Arch Soc. 1880.

- Catalogue of the Papers of James Boswell at Yale University: For ..., Volume 1.

- Davis, Michael C. (1991). The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire. Ardrishaig : Spindrift Press

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Eglinton Archive. Eglinton Country Park.

- Hall, Derek (2006). Scottish Monastic Landscapes. Stroud : Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-4012-8.

- Jamieson, Sheila (1997). Our Village. Greenhills Women's Rural Institute.

- Ker, Lee. Kilwinning Abbey. The Church of St Winning. Ardrossan : Arthur Guthrie.

- Lewin, Henry Grote (1925). Early British Railways. A short history of their origin & development 1801–1844. London: The Locomotive Publishing Co Ltd. OCLC 11064369.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- McJannet, Arnold F. (1938). Royal Burgh of Irvine. Glasgow : Civic Press.

- McMichael, George. Notes on the Way. Ayr : Hugh Henry.

- Mines Department. (1931). Catalogue of Plans of Abandoned Mines. Vol. V. (Scotland).

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. – II – Cunninghame. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Porterfield, S. (1925). Rambles Round Beith. Beith : Pilot Press.

- Reid, Donald L. (1999). Yesterdays Beith. Beith : DoE.

- Sanderson, Margaret H. B. (1972). Kilwinning at the time of the Reformation and its first Minister William Kilpatrick. Kilmarnock : AA&NHC.

- Scott Elliot, G. F. (1901). Edit. Fauna, Flora, & Geology of the Clyde Area. Glasgow : British Association for the Adavancement of Science.

- Service, John (1887). The Life & Recollections of Doctor Duguid of Kilwinning. Young J. Pentland.

- Urquhart, Robert H. et al. (1998). The Hearth Tax for Ayrshire 1691. Ayrshire Records Series V.1. Ayr : Ayr Fed Hist Soc ISBN 0-9532055-0-9.

- Whishaw, Francis (Reprinted and republished 1969) [1840]. The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland practically described and illustrated (3rd ed.). Newton Abbott: David & Charles (1842 edition - London: John Weale). ISBN 0-7153-4786-1.