Lands of Dallars

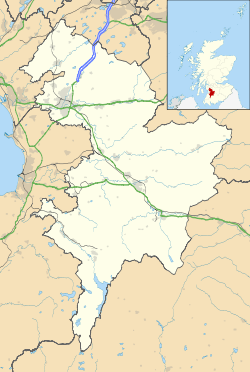

The Lands of Dallars or Auchenskeith (NS463337) form a small estate in East Ayrshire, Hurlford, Kilmarnock, Parish of Riccarton, Scotland. The present mansion house is mainly late 18th-century, located within a bend of the Cessnock Water on the site of older building/s. "Dullers or Dillers" was changed to "Auchenskeith" or "Auchinskeigh" (sic) as well as other variants and then the name reverted back nearer to the original form as "Dollars" and then finally "Dallars".[1] Dallars lies 3.25km south of Hurlford.

Lands of Dallars

| |

|---|---|

Lands of Dallars Location within East Ayrshire | |

| OS grid reference | NS403488 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Kilmarnock |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

For consistency the spellings 'Cuningham'; Dallars; Auchenskeith are used unless otherwise denoted (sic).

History

The estate lies on the old northern boundary of Cunninghame in the district of Kyle, bordering the lands of the Campbells of Loudoun to the north and the Wallaces to the west with Haining Place and the Barony of Haining-Ross lying upstream of the Cessnock Water to the north-west.[2]

The Laird's House, Farm and the Estate

Built on a low hill, the site gave a clear view of the surrounding area and originally would have been a fortified building such as a tower house. The later mansion house is a Category B Listed Building.[3] The date of the completion of the mansion house, 1779, is carved onto a gable skew of a garden shed at the walled garden. The mansion house is three storeys high; the porch may be a later addition. The flanking wings are a Victorian addition.[3] The estate buildings included stables, part of which date from around 1635; Mains Farm; a dovecot and a walled garden of brick enhanced by rusticated, finial ball topped, stone piers.[4]

The designed landscape of the estate policies has evolved during the 18th and 19th centuries, with an original plan of tree-lined parks developing into a less formal landscape.[5]

The estate's name was changed to 'Auchenskeith' following its purchase by the owner of the Auchenskeith estate near Dalry in North Ayrshire.

The 1855-57 OS Name Book gives most of the 1764 sasine properties now being held by a Colonel Cathcart and Dallars Mains farm is as well with a William Cunningham as occupier.[6]

The Lairds

An Archibald Dunlop who married a Craufurd of Craufurdland is thought to be the first named holder of "Dullers" (sic).

William Cunningham had sasine of the lands of Auchinskeith (sic) in 1712 and died in 1727.[7] A Dead bell was used to announce a death and rung with the funeral cortege, the Kilmarnock funeral bell carries the inscription "Kilmarnock, 1639". Its use was remembered by local inhabitants still alive in the 1850s and William's heir paid six pounds Scots for its use in 1727.[7]

Another William Cunningham of Auchenskeith inherited and became a burgess of Ayr in 1738.[7]

In 1764 a William Cunningham of Auchenskeith and his son, also William, had sasine of the 20s lands of Inchbean; 10s lands of Commonend; 40s lands of Whatriggs; 2 merk lands of Wester Mosside; 1 merk lands of Wester Mosside; 1 merk land of Easter Mosside; 2 1/2 merk lands of Hole of Commonhead and Clayslope; the 40d land of Commonhead, etc.[7] These lands in the Kilmarnock, Riccarton and Hurlford area had been held by Hugh, Earl of Marchmont.[7]

Captain William Cuningham held the lands in the late 1760s. On a visit to St Kitts in the West Indies he met and married Agnes Colquhoun, daughter of a plantation manager, Robert Colquhoun in 1770.[2] A John Begbie was a servant to Captain William Cuningham as shown by the Servants Tax Roll for 1777-78.[2]

A William Cuningham of Auchenskeith in 1767 sold the lands of Langlands to Dr.Park.[8]

In 1775 Alexander Cuningham, second son of William, became an Ayr burgess.

In 1803 Quintin MacAdam of Berbeth, later known as Craigengillan, was the owner of Dallars, however in 1805 he committed suicide, a trustee of the estate was Sir William Cuningham and the property was rented out.[2]

In 1847 the daughter of Colonel William MacAdam, Honoria Mary, married Edward Carleton Tufnell (b.1806. d.1886) and the couple lived at Dallars. Edward was a supporter of teacher training colleges and he acted in London from 1835 to 1846 as a commissioner of the Poor Laws.[9]

In 1878 their son, Carleton Tufnell (b.1848, d.1893) as a retired Royal Navy Commander, married a daughter of the 1st Viscount Anson.[10]

In 1885 Lady Adelaide Hastings, sister of Sophia, Marchioness of Bute, was in residence at Dallars whilst the estate was owned by the Honourable Jean MacAdam Cathcart of Craigengillan.[11]

In 1962 the Richards family purchased Dallars.[9]

Auchenskeith, Dalry

Recorded as 'Achin-skyich' by Timothy Pont and derived from the Scots Gaelic "Achad-na-sgitheach" meaning in English the "Field of thorns." The lands were originally a part of the Blair estates but were held by the Dunlops of that Ilk for three centuries.[12] Auchenskeith passed to the Cuninghams of Robertland, however in 1818 Sir William Cuningham of Robertland and Auchenskeith (Dallars), sold the Cuninghame estate of Auchenskeith to Colonel William Blair of Blair.[13]

Links with Robert Burns

Burns is recorded to have visited occasionally and Lochlea Farm lies just two miles away. Auchenskeith is said by Burns to have been in his mind when he wrote the suppressed stanza "Where Cessnock pours in gurgling sound." from "The Vision."[1] Sir William Cuningham's tutor was the Rev. James McKinlay, Minister of Kilmarnock's Laigh Kirk, who figures in the poem "The Ordination".[1] In 1789 Burns asked Captain Robert Riddell of Friars Carse to forward a letter to Sir William Cuningham.[14] The Lady 'C', referred to in a letter of 3 April 1786 to Robert Aitken in Ayr, may have been to Lady Cuningham.[14]

Sir William Cuningham of Auchenskeith and Robertland, acquired the Robertland House near Stewarton through marriage to Margaret Fairlie of Fairlie and he is known to have invited Robert Burns to Robertland.[15] Robert Burnes, uncle to the poet and latterly a resident in Stewarton, was a Robertland estate Land Steward.[14]

Alison Begbie or Elizabeth Gebbie is said to have been proposed to by Robert Burns. She was the daughter of a farmer and at the time of her courtship and was a servant employed at the Carnell House, then known as Cairnhill,[16] also close to the Cessnock Water. Alison Begbie may have been brought up at 'Old Place', near Shawsmill Farm and just a short distance downstream of Haining Place.[17] Burns was living at Lochlea Farm at this time.[18][19] John Gebbie was the tenant at Millhill Farm near Old Place and his brother Alexander was the miller at Cessnock Mill next to Millhill. A third brother, Thomas, farmed at Pearsland and had a daughter, Elizabeth, who was born on 22 July 1762 and is suggested to have been Robert Burns's love interest.[20]

Alison met Burns in 1781 near Lochlea Farm and it is of interest that a John Begbie was a servant to Captain William Cuningham as shown by the Servants Tax Roll for 1777-78.[2]

Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings

In 1845 Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings the daughter of the Marquess of Hastings had married Second Marquess of Bute, however he died and left his widow with a six month old son, who would become the Third Marquess, John Patrick Crichton Stuart.

The 2nd Marquess's brother, Lord James denied Lady Sophia and her son use of either Dumfries House at Cumnock or Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute. Lady Sophia rented Dallars House that was close to Loudoun Castle. They stayed at Dallars between 1849 and 1853 after which they moved to Mount Stuart.[2][21] She also rented Largo House near St Andrews for the summer months. In 1855-57 the Marchioness of Bute was still recorded as renting Dallars, with her sister Lady Adelaide Hastings in residence.[22][11]

Natural history

The site has a large Spanish Chestnut (Castanea sativa) that is said to have been planted by William and Agnes Cuningham.[2] The walled garden has the very rare Mistletoe (Viscum album) growing on an apple tree.

Cartographic evidence

In the 1662 map by Joan Blaeu based on the earlier map by Timothy Pont the name is given as 'Dullers' with a pale or fence built part way around the dwelling which was also wooded.[23] In 1732 the site is also shown as "Dullers".[24]

The 1747 William Roy map records the name "Dillars," with Dillars Shaw and Shaws Mill. Cesnock and Cesnock Yards lay on the opposite bank of the Cesnnock Water.[25]

An Auchenskeigh (sic) is shown on Andrew Armstrong's map of 1775 for the first time.[26] The name "Auchenskaith" (sic) is shown in 1821 on Ainslie's map.[27]

In 1776 Taylor and Skinner's map of 1776 shows the estate of 'Auchenskeich' (sic) as the property of Captain Cuningham, with a mansion house shown prior to the 1779 construction date of the central section of the present building.[28]

In 1828 the name "Dallars" replaces the variations of Auchenskeith.[29]

The 1855-57 Ordnance Survey Book gives the name in the form Dollars as confirmed by the factor, Kennedy Smith and William Woodburn of Shaws Mill.[30]

Etymology

A story is told of how the name 'Auchenskeith' was changed to 'Dollars' to reflect the dowry that Captain William Cuningham obtained from Robert Colquhoun upon marrying his daughter Agnes. Robert was a plantation owner in the West Indies where the currency was the 'Dollar' and this money was used to build the original house.[2]

The name Dullers was recorded in the 1660s, well before the marriage of Sir William Cuningham to Agnes Colquhoun in 1770. Dallars may derive its name from the Welsh dol for 'meadow' and ar for ploughed land as in 'Dollar' near Alloa. As stated its name was changed to 'Auchenskeith' following its purchase by the owner of the Auchenskeith estate near Dalry in North Ayrshire.[31]

In 1855-57 the official name was recorded as "Dollars" in the OS Name Book.[22]

Properties in the locale

In 1855-57 Shaw's Mill (corn) was held by the Duke of Portland and the miller was William Woodburn.[32]

'Old Place' to the east was originally the seat of the Campbells of Cessnock before they built Cessnock Castle. Old Place became part of the lands of Shawmill and the house was eventually abandoned.[33]

In 1857 "Dollars" (sic) is shown with "Old Place" replacing "Cesnock" and a walled garden, Mains Farm, etc. are shown.[34] Later OS maps do not show 'Old Place.'

Communications

The 1854-59 OS map shows that an Aird bridge once crossed the Cessnock Water and a dwelling, Aird Bridgend, stood on the western bank. A road ran down from the main road, crossed the bridge and led up to Aird Farm whilst another led up to the main road, joining it near Snodston Farm.[35]

Micro-history

John Galloway, Esq., of Barleith and Dollars (sic) Collieries built an institute in New Street Riccarton for the use of the working-men in the locality. The building still survives as a Community Centre run by East Ayrshire Council.[36]

See also

References

- Notes

- Boyle, Andrew (1996). The Ayrshire Book of Burns-Lore. Alloway Publishing Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 0-907526-71-3.

- Ayrshire Mansion - Dallars

- British Listed Buildings

- Close, Rob (2012). Ayrshire and Arran - Buildings of Scotland. Yale University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-300-14170-2.

- Parks and Gardens

- Scotland's Places

- Paterson, James (1863). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V.2., Part 2. James Stillie. p. 645.

- Paterson, James (1863). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V.2., Part 2. James Stillie. p. 646.

- Young, Alex (2017). The Country Houses, Castles and Mansions of East Ayrshire. Stenlake. p. 39. ISBN 9781840336306.

- County Families of Scotland

- Young, Alex (2017). The Country Houses, Castles and Mansions of East Ayrshire. Stenlake. p. 38. ISBN 9781840336306.

- Dobie, p.49

- Dobie, p.50

- Boyle, Andrew (1996). The Ayrshire Book of Burns-Lore. Alloway Publishing Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 0-907526-71-3.

- Hogg, Page 105

- Hunter, Page 169

- Mackay, Page 84

- Robert Burns Encyclopedia Retrieved : 9 February 2020

- Muir, John (1896). Burns at Galston and Ecclefechan. John Muir. p. 7.

- Mackay, James (1992). Burns. A Biography of Robert Burns. Alloway Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 0-907526-85-3.

- Hannah, p.7

- Scotlands Places - Dollars

- Blaeu Atlas Maior, 1662-5 Volume 6 Blaeu Atlas Maior 1662-5, Volume 6. Coila Provincia

- The South Part of the Shire of Air [i.e. Ayr, containing Kyle and Carrick / by H. Moll.]]

- 1747-55 - William ROY - Military Survey of Scotland

- Armstrong, Andrew, 1700-1794. A new map of Ayrshire of 1775.

- Ainslie's Map of the Southern Part of Scotland. 1821.

- G Taylor and A Skinner's map

- Thomson, John, Northern Part of Ayrshire. Southern Part. 1828.

- Ordnance Survey Name Books Ayrshire OS Name Books, 1855-1857 Ayrshire volume 53 OS1/3/53/53

- Johnston, Page 102

- Scotland's Places

- Mackay, p.84

- Ayrshire XXIII.7 Survey date: 1857. Publication date:1893

- 1854-1859 - ORDNANCE SURVEY - 25 inch 1st edition maps of Scotland

- McKay, Archibald (1880) The History of Kilmarnock. Pub. Archibald McKay, Kilmarnock. P. 346.

- Sources and Bibliography

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to Ayr & Wigton. 1884. Vol. IV. Shedden-Dobie, John. The Church of Dunlop.

- Bayne, John F. (1935). Dunlop Parish - A History of Church, Parish, and Nobility. Edinburgh : T. & A. Constable.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Fullarton, John (1864). Historical Memoir of the family of Eglinton and Winton. Ardrossan : Arthur Guthrie.

- Hannah, Rosemary The Grand Designer.

- Hogg, Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns. The Patriot Bard. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing.ISBN 9781845964122

- Johnston, J. B. (1903). Place-names of Scotland. Edinburgh : David Douglas.

- Mackenzie, W. Mackay (1927). The Medieval Castle in Scotland. Pub. Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- Mackay, James. A Biography of Robert Burns. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-85158-462-5.

- MacIntosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Nights Entertainments: A Descriptive Guide to the History, Traditions, Antiquities, etc. of the County of Ayr. Pub. Kilmarnock.

- McMichael, George (c. 1881 - 1890). Notes on the Way Through Ayrshire and the Land of Burn, Wallace, Henry the Minstrel, and Covenant Martyrs. Hugh Henry : Ayr.

- Ness, John (1990). Kilwinning Encyclopedia. Kilwinning & District Preservation Society.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. - II - Cunninghame. Part II. Edinburgh : J. Stillie.