Lake Faguibine

Lake Faguibine is a lake in Mali on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert situated 80 km west of Timbuktu and 75 km north of the Niger River to which it is connected by a system of smaller lakes and channels. In years when the height of the annual flood of the river is sufficient, water flows from the river into the lake. Since the Sahel drought of the 1970s and 1980s the lake has been mostly dry. Water has only rarely reached the lake and even when it has done so, the lake has been only partially filled with water. This has caused a partial collapse of the local ecosystem.

| Lake Faguibine | |

|---|---|

Lake Faguibine (spear-shaped) from space, April 1991. The River Niger is shown at the bottom right hand corner, Lake Oro at the lower left and Lake Fati lower right | |

Lake Faguibine | |

| Location | Mali |

| Coordinates | 16°45′N 4°0′W |

| Primary inflows | Niger River |

Lake Faguibine system

The lake forms part of a system of five interconnected low-lying depressions that fill to variable depths depending on the extent of the annual flood of the Niger River. Lake Faguibine is by far the largest of these depressions with an area of 590 km2.[1][2] The low annual rainfall in the area (less than 200 mm) only has a marginal effect on the water levels in the depressions.

The depressions are connected to the Niger River by two channels. The more southerly Kondi channel (64 km in length) branches from the Niger a few kilometers downstream of Diré[3] and then meanders across the Killi floodplain. The larger and more northerly Tassakane channel (104 km in length) branches from the Niger further downstream near Korioumé and then meanders across the Kessou floodplain. The two channels unite to form a single channel to the east of Goundam which after another 20 km flows into the southern end of Lake Télé.[4] Lake Télé is connected at its northern end to Lake Takara. Water flows out of the northern end of Lake Takara, across a rocky sill at Kamaïna and then turns west passing the village of Bintagoungou to reach Lake Faguibine.

Both Lake Télé and Lake Takara need to be completely filled before the water can flow over the sill at Kamaïna and begin to supply Lake Faguibine. In a similar manner two depressions to the east of Lake Faguibine (Lake Kamango and Lake Gouber) only start to fill once Lake Faguibine is full.[5] To completely fill the 590 km2 of Lake Faguibine requires about 4 km3 of water. This represents around 17 percent of the average discharge of the Niger (1970-1998) at Diré.[6]

The lake bed is very fertile and the ideal situation for the sedentary farmers is when the lake is only partially filled. This allows crops to be cultivated around the border of the lake and the growth of Echinochloa stagnina ("bourgou") in low-lying areas to provide dry season pasture. This regime requires much less water – only around 0.5 km3.[7]

River Niger and the annual flood

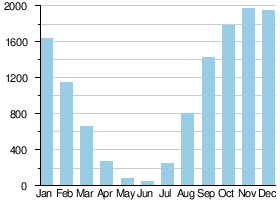

Average monthly flow (m3/s) at the Diré hydrometric station over the period 1924-1992[8] |

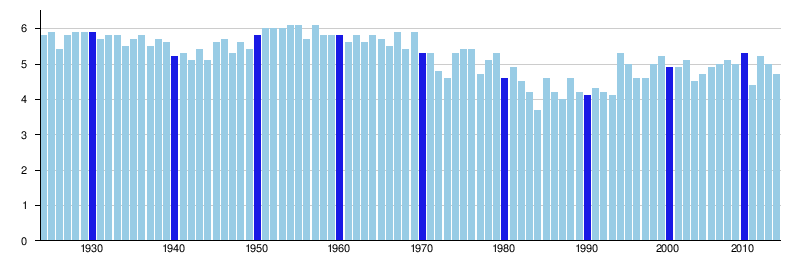

The filling of Lake Faguibine with water from the Niger River is dependent on both the height of the annual flood and the free flow of water along the complex 170 kilometres (110 mi) route linking the lake to the river. The annual flood of the Niger River is a result of the heavy rainfall in Guinea and for its important tributary, the Bani River, that in northern Côte d'Ivoire and southwest Mali. In all areas the rainfall peaks in the month of August.[9] The amount of rain, and thus the height of the flood, varies from year to year. In years with high flood levels such as between 1924-1930 and 1951-1955 the lake is completely filled. In years with low rainfall the lake can dry out completely. In the 20th century this occurred in 1914, 1924 and 1944 and became a regular occurrence after the severe drought that began in the late 1970s.[10][11] Low flood levels are exacerbated by the construction of dams on the Niger river or it tributaries that retain the floodwater and thus attenuate the maximum height of the flood downstream. Of the existing dams, the most significant is the Sélingué Dam on the Sankarani River in southwest Mali that can store 2.2 km3 of water.[12] There are plans to build a new large dam, the Fomi dam, on the Niandan tributary in Guinea that will store almost 3 times the amount of water as that stored by the Sélingué dam. If constructed this dam would further reduce the intensity of the annual flood.[13]

One of the major aims of a United Nations Sudano-Sahelian Office (UNSO) project (1986-1990) was to improve the connection of the Niger with Lake Faguibine and to cut some of the meanders of the Kondi channel. The project was interrupted by the Tuareg Rebellion (1990–1995). During the 1980s the low height of the annual floods created intense competition for water and the local population obstructed the flow in the channels and installed fish-traps. Since 2003, a German aid organization, Mali-Nord, have financed the construction of irrigated areas that leave the flow of water in the channels unimpeded.[14]

In 2006 the Government of Mali created the "Office pour la Mise en Valeur du système Faguibine" (OMVF) to maintain the channels and to stabilize the sand dunes by planting Euphorbia balsamifera and eucalyptus.[15]

Much of the vegetation that stabilized the dunes perished in the drought that started in the late 1970s. As a result, sand is blown and washed into the channels. The sill at Kamaïna is next to large dunes and is particularly vulnerable to the accumulation of sand. Starting in 2002, the local villages cooperated in removing the sand and since 2006 the efforts have been coordinated by the OMVF and supported by the World Food Program.[16] In October 2008, around a 1000 people worked for 6 days to clear the sand.[17]

In a project funded by the government of Norway, the United Nations Environment Program is studying the Lake Faquibine ecosystem and looking at ways in which the management of land and the hydrological cycle could be improved.[18] The project is planned to run between 2008 and 2015 with an initial budget of 1 million USD.[19]

Annual maximum height (in meters) of the Niger River at the Diré hydrological station[20]

Notes

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 2

- Map at a scale of 1: 500,000 that includes the Lake Faguibine system (PDF), Mali-Nord Programme, 2005.

- Map at a scale of 1: 100,000 showing the Kondi and Tassakane channels (PDF), Mali-Nord Programme, 2007.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 14

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 18

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 20

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 20

- Composite Runoff Fields V 1.0: Diré, University of New Hampshire/Global Runoff Data Center, retrieved 15 Jan 2011.

- Zwarts, Cissé & Diallo 2005, pp. 18–19.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 21.

- Zwarts & Bakary 2005, p. 85.

- Zwarts, Cissé & Diallo 2005, pp. 22–23.

- Zwarts, Cissé & Diallo 2005, pp. 27–28.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, pp. 15–16.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 34.

- Mali: Restoring Lake In Desert, Farmers Keep Hunger Away, World Food Program, 2009, archived from the original on 2009-12-26, retrieved 2009-12-28.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 18.

- Rehabilitating Lake Faguibine Ecosystem: Project factsheet (PDF), United Nations Environment Program, retrieved 2009-12-21.

- Hamerlynck, Chiramba & Pardo 2009, p. 5.

- Hydrological Information System, Diré, Centre Régional du Projet NIGER-HYCOS, retrieved 19 June 2015.

References

- Hamerlynck, O.; Chiramba, T.; Pardo, M. (2009), Gestion des écosystèmes du Faguibine (Mali) pour le bien‐être humain : adaptation aux changements climatiques et apaisement des conflits. Version 5 April 2009 (in French), United Nations Environment Program, archived from the original on 25 July 2011, retrieved 2009-12-20.

- Zwarts, Leo; Cissé, Navon; Diallo, Mori (2005), "Hydrology of the Upper Niger", in Zwarts, Leo; van Beukering, Pieter; Kone, Bakary; et al. (eds.), The Niger, a lifeline: Effective water management in the Upper Niger Basin (PDF), Veenwouden, the Netherlands: Altenburg & Wymenga, pp. 15–39, ISBN 90-807150-6-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24, retrieved 2011-01-17. Also published in French with the title Le Niger: une Artère vitale. Gestion efficace de l’eau dans le bassin du Haut Niger.

- Zwarts, Leo; Bakary, Kone (2005), "People in the Inner Niger Delta", in Zwarts, Leo; van Beukering, Pieter; Kone, Bakary; et al. (eds.), The Niger, a lifeline: Effective water management in the Upper Niger Basin (PDF), Veenwouden, the Netherlands: Altenburg & Wymenga, pp. 79–86, ISBN 90-807150-6-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24, retrieved 2011-01-17.

Further reading

- Chudeau, René (1918), "La dépression du Faguibine", Annales de Géographie (in French), 27 (145): 43–60, doi:10.3406/geo.1918.4154.

External links

- Drying of Lake Faguibine at NASA Earth Observatory

- Ecosystem Management for improved Human Well-Being in the Lake Faguibine System: conflict mitigation and adaptation to climate change (PDF), United Nations Environment Program, retrieved 2009-12-20. An incomplete draft dated 02-10-2008 of an English version of the Hamerlynck UNEP document.

- Mali-Nord: a German foreign aid program funded by Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) and Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) that has been operating in northern Mali since 1994. Mostly in German but a few files in French and one in English by Andrew Dillon: Measuring the Programme Mali-Nord’s Impact.