La Matanza

La Matanza ("The Massacre") was a peasant uprising that occurred on January 22 of 1932 in the western departments of El Salvador and was suppressed by the government, then led by Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. The Salvadoran army, being vastly superior in terms of weapons and soldiers, executed those who stood against it. The rebellion was a mixture of protest and insurrection which ended in ethnocide,[4] claiming the lives of an estimated 10,000 and 40,000[5] peasants and other civilians, many of them Pipil people.[6]

| 1932 Salvadoran farmer uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

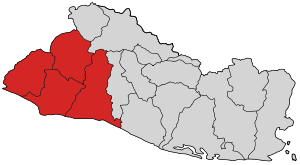

Map of the Salvadoran districts affected by the uprising. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Salvadoran rebels |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

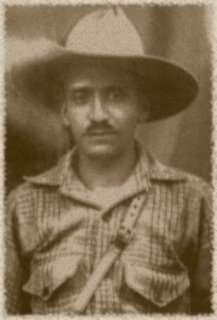

Chief Feliciano Ama † Agustín Farabundo Martí † Francisco Sánchez † |

Maximiliano Hernández Martínez José Tomás Calderón Osmín Aguirre y Salinas Salvador Ochoa Saturnino Cortez | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| between 10,000 and 40,000,[1] 25,000 dead[2] | |||||||

| [3][2] | |||||||

Background

Social unrest in El Salvador had begun to grow in the 1920s, primarily because of the perceived abuses of the political class, and the broad social inequality between the landowners and the Pipils.[7][8] A U.S. Army officer stated in 1931 that, "there appears to be nothing between these high-priced cars, and the oxcart with its barefoot attendant. There is practically no-middle class."[9] The policies of the latifundia had left 90 percent of the country's land in the hands of 14 families, 'los catorce', who used the land for the cultivation of the cash-crop coffee.[10]

The Salvadoran economy had largely depended on the coffee bean during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so much so that this period is known as the "Coffee Republic" era. The national coffee-growing industry had grown with the accumulation of riches of a small group of landowners and merchants[8][11] who had purchased large portions of land and employed a great number of peasants, many of whom were indigenous.[12] Working conditions at the haciendas were very poor. By 1930, pay consisted of two tortillas and two spoonfuls of beans at the beginning and end of each day.[13] Furthermore, workers were paid in scrip which could only be redeemed at stores controlled by the plantation owners. This led to local monopolies which drove up the price of food. It is estimated that food costs for laborers were no more than $0.01 per day,[13][14] creating considerable profits for plantation owners.

In 1932, the head of a U.S. delegation in San Salvador, W.J. McCafferty, wrote a letter to his government explaining the Salvadoran situation, stating that farm animals were worth more than workers as they were in high demand and had better commercial value.[13]

The global economic situation caused by the Great Depression fostered the lack of opportunities in countries such as El Salvador.[15] Due to the drop in coffee prices, several haciendas were closed and many peasants lost their jobs, creating deep economic turmoil.[16] Although the crisis affected people all over the country (and almost all of Latin America),[17] the crisis was more acute in western El Salvador. The policies of presidents Pío Romero Bosque and Arturo Araujo had stripped almost all land from the local peasants.[18] This area was heavily populated by the indigenous Pipils.[19] The indigenous people, separated from the scarce economic progress, sought help from their own leaders. Although the law did not grant any powers or official recognition of the caciques, the natives respected and obeyed their authority.[20] The political class had often sought the approval of the caciques in order to gain support of their people during elections.[16]

In order to alleviate the economic crisis, the Pipil had organized themselves into cooperative partnerships, through which employment was provided in exchange for their participation in Catholic festivities. The cacicques led these partnerships, and represented the unemployed before the authorities and supervised their work.[16] Feliciano Ama, for example, was one of the most active caciques and was highly esteemed by the indigenous population.[21] Ama had arranged for economic assistance from president Romero in exchange for supporting his candidacy. On the other hand, the crisis intensified due to the permanent conflict between the indigenous and non-indigenous populations.[22] Naturally, the non-indigenous people had better relations with the government; when riots or fighting occurred, it was indigenous leaders who were arrested and sentenced to death.

The rebellion was also preceded by political instability. El Salvador had been ruled since 1871 by economic liberal elites who had presided over a long period of relative stability. By World War I, the presidency effectively rotated between the Meléndez and Quiñónez families in quasi-dynastic succession. In 1927, Pío Romero Bosque was elected President and embarked on political liberalisation that led to what was arguably the first free election in Salvadoran history, which was held in 1931.

Arturo Araujo was elected during the 1931 elections, amid a severe economic crisis. After a military coup, vice president Maximiliano Hernández Martínez assumed control of the country in December 1931, marking the beginning of El Salvador's military dictatorship.[23] Hernández Martínez's regime was characterized by the severity of its laws and punishments. For example, theft was punished with the amputation of a hand.[24] Martínez strengthened police forces and was especially aggressive in matters of rebellion, issuing the death penalty against anyone who opposed the regime.[16]

Though Martínez's rule may have satisfied the military, popular discontent continued to build and the government's opponents continued to agitate. Within weeks, communists, believing the country was ready for a peasant rebellion, were plotting an insurrection against Martínez.

Causes of the conflict

Many incidents and situations directly influenced the conflict. On one side, the Salvadoran Army was organized to fend off any uprisings. The peasants (indigenous and non-indigenous) were beginning to rise up against the local authorities in an unorganized manner. Finally, the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCS) became involved in activities which led to the uprising.

The Salvadoran Army in 1932

The army was organized into regiments of infantry, artillery, machine guns and cavalry. The most commonly used weapon was the German-made Gewehr 98.[25] The air force did not play a decisive role, as its participation at the time was limited to reconnaissance.

The army was under the direct orders of the President and had the defense of the State as its primary objective.[26] The different security forces included the National Police, the National Guard and the Hacienda Police.

Preceding peasant rebellions

Given the circumstances of poverty and inequality, some peasants who were stripped of their land and subjected to poorly paid work began to rebel against the landlords and the authorities. This began on an individual basis, which made it easier for the authorities to detain or threaten the rebels. The big landlords had close ties to military authorities, so defense of the haciendas was performed by official security forces.[27]

After several arrests, the peasants began to organize in a low profile manner, lacking any hierarchical system. Therefore, efforts remained isolated and disperse and were easily suppressed. Security forces arrested rebels, many of whom were later sentenced to death by firing squad or hanging.[16] There is no data on the number of executions carried out in the weeks prior to the massacre. However, it is known that many peasant leaders were convicted, as were many public officials who collaborated with them in any way.[16]

The Communist Party of El Salvador

At the same time as the conflicts between indigenous people, peasants, landowners and authorities, the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCS) began distributing pamphlets and registering new members.[28] Activities were fuelled by frustration over broken promises by the government and political parties.[29] The communist leaders, led by Farabundo Martí, had built a political organization that managed to obtain the sympathy of the population. After the coup d'état of 1931, the press gained more freedom to express dissenting views, and the PCS increased the spread of their revolutionary message.[16][27]

Although they lacked a definite party platform, the PCS registered candidates for the January 1932 elections. Electoral processes in that era were subject to serious criticism. Votes had to be made publicly with the authorities. This practice broadly favored official candidates by sowing fear among voters and hindering democratic participation.[16][30]

After the elections, accusations of fraud led the communist leadership to abandon faith in the electoral process and take the path of uprising.[29]

The uprising was planned for mid-January 1932, and included the support of communist-sympathizers in the military. Before the revolt could take place, police arrested Martí and other communist leaders.[31] Authorities seized documents proving the planned insurrection, which were used as evidence in military trials.[16]

Despite the moral and organizational blow suffered by the PCS, the insurrection was not canceled. By the end of January 1932, the national situation had become chaotic. Security forces detained any groups or individuals involved in subversive or revolutionary acts.[32] Meanwhile, the indigenous population in the West began to revolt in protest of poor living conditions. There is no evidence to support the position that the peasant uprising was carried out by the PCS, but due to the dates on which both uprisings occurred, the armed forces responded equally to both movements.

The uprising

In the late hours of January 22, 1932, thousands of peasants in the western part of the country rose up in rebellion against the regime. Rebels led by the Communist Party and Agustín Farabundo Martí, Mario Zapata and Alfonso Luna, attacked government forces with support that was largely from the indigenous Pipils. Armed primarily with machetes,[4] peasants attacked haciendas and military barracks, gaining control over several towns, including Juayúa, Nahuizalco, Izalco, and Tlacopan. Barracks in towns such as Ahuachapán, Santa Tecla, and Sonsonate resisted the attack and remained under government control. It is estimated that peasant rebels killed no more than 100 people.[33] Confirmed deaths include about twenty civilians and thirty soldiers.[34][35]

The first city to be taken was Juayúa, where landowner Emilio Radaelli was assassinated. His wife was raped and later murdered. Several other military leaders and government officials were also executed.[8]

Differing accounts of the event exist, and it is difficult to ensure which is correct since there were very few survivors of the rebellion. It is said that indigenous peoples attacked privated property and committed vandalism and other crimes against entire towns. There is evidence to support this claim, though it is possible that these were merely opportunists joining the uprising to carry out criminal acts. The participation of the indigenous peoples and peasants in the looting cannot be conclusively confirmed or denied. The primary motive of the events, however, can be guaranteed.[36][27]

The relationship between the peasants and the Communist Party is also controversial. The coincidental timing of both uprisings and the similar causes lead to the conclusion that they were linked, or even coordinated. Some theories contend that the PCS used the economic turmoil to convince the peasants to act together and rise against the regime.[37] Little to nothing is known about the relation between the two groups.[36] Authors such as Erik Ching affirm that the PCS could not possibly have directed the insurrection, as the party held little influence over the peasant population and was hampered by in-fighting.[35][38]

Regardless, the government made no distinction between either movement.

Government reaction

The government reacted swiftly, recovering lost territory by means of a military deployment aimed at suppressing the rebellion.[4] With their superior training and technology, the government troops needed only a few days to defeat the rebels.

General José Tomás Calderón enjoyed an abundance of troops and weapons:

The use of superior armament was the decisive element in the confrontation and the stories speak of “waves of Indians, blown away by machine guns.” This was followed by extreme suppression, executed by units of the Army, Police, and National Guard, as well as volunteers organized into “civil guards.”

— Historia de El Salvador. Convenio Cultural México-El Salvador, Ministerio de Educación. 1994. p. 133.

The civil guards were volunteers who took up service for the security forces to assist in patrolling, and when necessary, fought alongside the military.[39]

On January 23, the Canadian warships Skeena and Vancouver docked at the Port of Acajutla. The ships were requested by Britain, in order to protect any British citizens in the country. U.S. ships arrived shortly after.[40] The ships' crews were also prepared to assist the Salvadoran government in quelling the rebellion. However, the chief of operations in El Salvador turned down the offer, stating:[14]

The chief of Operation of the Western Zone of the Republic, Major General José Tomás Calderón, presents his compliments on behalf of the government of General Martínez and of himself, to Admiral Smith and Commander Brandeur, of the Rochester, Skeena, and Vancouver, I am pleased to announce that peace in El Salvador is restored, that the communist offensive has been completely suppressed and dispersed, and that complete extermination will be achieved. 4,800 Bolsheviks were wiped out.

— José Tomás Calderón

Although the exact number of deaths in the first 72 hours after the uprising is unknown, several historians agree that it was around 25,000 people.[34][41][42] Those who were captured alive were sent to trial and inevitably sentenced to death.

After the rebellion, peasant leader Francisco Sánchez was hanged. His counterpart, Feliciano Ama, was lynched and his body was later hung in the town square while schoolchildren were forced to attend.[30]

In the areas around Izalco, anyone found carrying a machete, and anyone with indigenous features or clothing, was accused of subversion and found guilty.[15] In order to ease the work of the security forces, all those who had not participated in the insurrection were invited to present themselves in order to obtain documents which declared their innocence. Upon arrival they were examined, and those with indigenous features were arrested. They were shot in groups of 50 in front of the wall of the town church, Iglesia de La Asunción. Several were forced to dig mass graves, which they were thrown into after being shot.[13] The houses of those found guilty were burned and the surviving inhabitants were shot.

According to the commander of the operacion, 4,800 members of the PCS were killed,[13] although this figure is difficult to verify.

After the conflict, survivors attempted to flee to Guatemala; in response, president Jorge Ubico ordered the border to be closed, handing over anyone who attempted to cross to the Salvadoran army.[14]

As resolution of the conflict, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador issued Legislative Decree No. 121 on July 11, 1932, which granted unconditional amnesty to anyone who committed crimes of any nature in order to "restore order, repress, persecute, punish and capture those accused of the crime of rebellion of this year."[36]

Aftermath

Having put down the rebellion, the government of Hernández Martínez began a process of repression of the opposition, and utilized the voter registry to intimidate or execute those who had declared themselves opponents of the government.[16]

As the killings particularly targeted people of indigenous appearance, dress, or language, in the decades that followed, Salvadoran indigenous peoples increasingly abandoned their native dress and traditional languages from fear of further reprisals.[43][44][45][15] The events brought about the extermination of the majority of the Pipil-speaking population, which led to a near total loss of the spoken language in El Salvador.[46][47] The indigenous population abandoned many of their traditions and customs out of fear of being arrested. Many of the indigenous people who did not participate in the uprising stated that they did not understand the motivation of the government's persecution.[48]

Over the years, the indigenous population has fallen to the point of near extinction in the 21st century. In the decade following the uprising, military presence in the area was persistent with the objective of keeping the peasants under control so that the events did not recur. After the dictatorship of Hernández Martínez, the method of preventing peasant discontent changed from repression to social reforms which benefitted them (at least momentarily).[49][50]

In 2010, president Mauricio Funes apologized to the indigenous communities of El Salvador for the brutal acts of persecution and extermination carried out by previous governments. The statement was made during the inauguration of the First Congress of Indigenous Peoples. "In this context and this spirit, my government wishes to be the first government to, on behalf of the State of El Salvador, of the people of El Salvador, and of the families of El Salvador, make an act of contrition and apologize to the indigenous communities for the persecution and extermination of which they were victims during so many years," said the president.[51]

Commemorations

In the town of Izalco, the uprising is commemorated on every January 22. Media coverage is moderate, but the commemoration is supported by municipal authorities who pay tribute to all who were killed during the event. Speakers include people who lived through the event, and relatives of Feliciano Ama.[4][52]

See also

References

- University of California, San Diego (2001). "El Salvador elections and events 1902–1932". Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- http://html.rincondelvago.com/oligarquia-cafetalera-en-santa-tecla-y-santa-ana.html

- University of California, San Diego (2001). "El Salvador elections and events 1902–1932". Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- Payés, Txanba (January 2007). "El Salvador. La insurrección de un pueblo oprimido y el etnocidio encubierto" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- University of California, San Diego (2001). "El Salvador elections and events 1902–1932". Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- CISPES (January 27, 2007). "La sangre de 1932" (in Spanish). Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- "El Salvador en los años 1920–1932" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- Armed Forces of El Salvador. "Revolución 1932" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. W.W. Norton. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, El Salvador, In Depth, Negotiating a settlement to the conflict, http://www.ucdp.uu.se/gpdatabase/gpcountry.php?id=51®ionSelect=4-Central_Americas#, viewed on May 24, 2013

- Moreno, Israel (December 1997). "El Salvador: Un paisito en peligro de extinción". Revista Envío (in Spanish). Universidad Centroamericana (189). Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- de La Rosa Municio, Juan Luis (January 2006). "El Salvador: Memoria histórica y organización indígena" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- Martínez, Néstor (January 13, 2007). "Las venas abiertas de los indígenas en El Salvador". Diario Co Latino (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Causas y efectos de la Insurrección Campesina de enero de 1932 (in Spanish). San Salvador: University of El Salvador. 1995.

- de La Rosa Municio, Juan Luis (January 2006). "El Salvador: Memoria histórica y organización indígena" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Ministerio de Educación de la República de El Salvador (1994). Historia de El Salvador, tomo II (in Spanish). San Salvador: MINED.

- Acosta Iturra, Mónica Gabriela (June 7, 2006). "La Crisis de 1929 y sus repercusiones en América Latina" (in Spanish). Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Historia de El Salvador" (in Spanish). Preselección Empresarial. Archived from the original on September 17, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Historia de Suchitoto" (in Spanish). Oficina Municipal de Turismo de Suchitoto. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Imagino a aquellos hombres fuertes". Diario Co Latino (in Spanish). March 29, 2003. Archived from the original on April 28, 2003. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Martínez Peñate, Oscar. "José Feliciano Ama es un mártir popular" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- "La insurrección indígena de 1932". El Periódico Nuevo Enfoque (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- el Rojo, Heródoto. "El Salvador, de la esperanza a la desilusión" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Escobar, Iván (April 2, 2005). ""Jornadas de abril y mayo del 44" cumplen hoy 61 años". Diario Co Latino (in Spanish). Archived from the original on April 13, 2005. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- "Revolución 1932" (in Spanish). Fuerza Aérea de El Salvador. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- "El Salvador: La Segunda Guerra Mundial". Exordio (in Spanish). July 20, 2004. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- Candelario, Sheila (January–June 2002). "Patología de una Insurrección: La prensa y la Matanza de 1932". Istmo: Revista virtual de estudios literarios y culturales centroamericanos (in Spanish). 3. ISSN 1535-2315. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Álvarez, Joyce; Grégori, Ruth. "1932, las dos caras de una historia por contar". El Faro (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- Santacruz, Domingo (November 12, 2006). "Aproximación a la historia del Partido Comunista Salvadoreño" (in Spanish). El Centro de Documentación de los Movimientos Armados. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- Galeano, Eduardo (2007). El siglo del viento (in Spanish). Volume 3 (10th ed.). Siglo XXI de España Editores. p. 136. ISBN 978-84-323-1531-2. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- "Farabundo Martí". Avizora (in Spanish). Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Grégori, Ruth; Álvarez, Joyce (January 22, 2007). "Las huellas de la muerte en el presente de los indígenas". El Faro (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- Anderson, Thomas P. (1971). Matanza: El Salvador's Communist Revolt of 1932. Lincoln: University of Nebraska. pp. 135–6. ISBN 9780803207943.

- Carlos Henríquez Consalvi and Jeffrey Gould (Directors). 1932, cicatriz de la memoria (Documentary) (in Spanish). Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen.

- Ching, Erik (September 1995). "Los archivos de Moscú: una nueva apreciación de la insurrección del 32". Tendencias (in Spanish). San Salvador. 3 (44).

- Cuellar Martinez, Benjamín (October 2004). "El Salvador: de genocidio en genocidio" (in Spanish). 59 (672). San Salvador: Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas: 1083–1088. ISSN 0014-1445. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Entrevista a Erik Ching". Diario Co Latino (in Spanish). Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- Ching, Erik (1998). "In Search of the Party: The Communist Party, the Comintern, and the Peasant Rebellion of 1932 in El Salvador". The Americas. 55 (2): 204–239. doi:10.2307/1008053. JSTOR 1008053.

- "Guardia Civil-Historia" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior Español. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011.

- Milner, Marc (March 1, 2006). "The Invasion Of El Salvador: Navy, Part 14". Legion Magazine. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- "Feliciano Ama, líder de la insurrección indígena de 1932". El Periódico Nuevo Enfoque (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 18, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- Argueta, Ricardo (April 4, 2007). "Los grandes debates en la historiografía económica de El Salvador durante el siglo XX". Boletín AFEHC (in Spanish) (29). ISSN 1954-3891.

- "El Salvador: before the war," Enemies of War, PBS companion web site for the documentary film of the same name. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- Virginia Garrard-Burnett. "1932: Scars of memory (Cicatriz de la memoria) (film review), The American Historical Review, 109:2 (April 2004), pp. 575-576. Retrieved from the JSTOR database May 20, 2013.

- Deborah Decesare. "Timeline: the massacre in El Salvador," companion website to the documentary film Destiny's Children. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- de Maeztu, Ramiro (February 16, 1932). "La defensa de la Hispanidad". Acción Española (in Spanish). Vol. I no. 5. Madrid. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Una experiencia de recuperación de la lengua y la cultura indígena en el Salvador" (PDF). Suatea (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "El Salvador: lucha contra la pobreza". Terra El Salvador. Archived from the original on April 27, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Kohan, Néstor. "Roque Dalton y Lenin leídos desde el siglo XXI". Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Reforma agraria y desarrollo rural en El Salvador". ICARRD. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Presidente Funes pide perdón a comunidades indígenas por persecución y exterminio de otros gobiernos". El Salvador Noticias. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- García Dueñas, Lauri (January 23, 2005). "Ancianos de Izalco recuerdan masacre de miles de indígenas". Retrieved April 22, 2007.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Thomas P. (1971). Matanza: El Salvador's Communist Revolt of 1932. Lincoln: University of Nebraska. pp. 135–6. ISBN 9780803207943.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Bry, John (May 18, 2004). "Review of 1932 – Scars of Memory (Cicatriz de la Memoria), A film by Jeffrey Gould and Carlos Henriquez Consalvi". Kacike. [On-line Journal]. ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original on July 21, 2006. Retrieved June 30, 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keogh, Dermot (1982). "El Salvador 1932. Peasant Revolt and Massacre". The Crane Bag. 6 (2): 7–14. JSTOR 30023895.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Urbina Gaitán, Chester Rodolfo; Urquiza, Waldemar, eds. (2009). "El levantamiento campesino-indígena de 1932" (PDF). Historia 2: El Salvador (in Spanish). San Salvador: MINED. pp. 113–116.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Gould, Jeffrey L. (2008), To Rise in Darkness: Revolution, Repression, and Memory in El Salvador, 1920–1932, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-4228-1

- Alegría, Claribel (1989). Ashes of Izalco: a novel. Willimantic, CT : New York, NY: Curbstone Press ; Distributed to the trade by the Talman Co. ISBN 0915306840.