Cystine

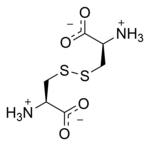

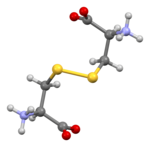

Cystine is the oxidized dimer form of the amino acid cysteine and has the formula (SCH2CH(NH2)CO2H)2. It is a white solid that is slightly soluble in water. It serves two biological functions: a site of redox reactions and a mechanical linkage that allows proteins to retain their three-dimensional structure.[1]

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.270 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12N2O4S2 | |||

| Molar mass | 240.29 g·mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Formation and reactions

It is common in many foods such as eggs, meat, dairy products, and whole grains as well as skin, horns and hair. It was not recognized as being derived of proteins until it was isolated from the horn of a cow in 1899.[2] Human hair and skin contain approximately 10–14% cystine by mass.[3] It was discovered in 1810 by William Hyde Wollaston.

Redox

It is formed from the oxidation of two cysteine molecules, which results in the formation of a disulfide bond. In cell biology, cystine residues (found in proteins) only exist in non-reductive (oxidative) organelles, such as the secretory pathway (ER, Golgi, lysosomes, and vesicles) and extracellular spaces (e.g., ECM). Under reductive conditions (in the cytoplasm, nucleus, etc.) cysteine is predominant. The disulfide link is readily reduced to give the corresponding thiol cysteine. Typical thiols for this reaction are mercaptoethanol and dithiothreitol:

- (SCH2CH(NH2)CO2H)2 + 2 RSH → 2 HSCH2CH(NH2)CO2H + RSSR

Because of the facility of the thiol-disulfide exchange, the nutritional benefits and sources of cystine are identical to those for the more-common cysteine. Disulfide bonds cleave more rapidly at higher temperatures.[4]

Cystine-based disorders

The presence of cystine in urine is often indicative of amino acid reabsorption defects. Cystinuria has been reported to occur in dogs.[5] In humans the excretion of high levels of cystine crystals can be indicative of cystinosis, a rare genetic disease.

Biological transport

Cystine serves as a substrate for the cystine-glutamate antiporter. This transport system, which is highly specific for cystine and glutamate, increases the concentration of cystine inside the cell. In this system, the anionic form of cystine is transported in exchange for glutamate. Cystine is quickly reduced to cysteine. Cysteine prodrugs, e.g. acetylcysteine, induce release of glutamate into the extracellular space.

Cystine hair nutritional supplements

Cysteine supplements are sometimes marketed as anti-aging products with claims of improved skin elasticity. Cysteine is more easily absorbed by the body than cystine, so most supplements contain cysteine rather than cystine. N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) is better absorbed than other cysteine or cystine supplements.

See also

- Lanthionine, similar with mono-sulfide link

- Protein tertiary structure

- Sullivan reaction

- Cystinosis

References

- Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. (2000) Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry. 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- "cystine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 27 July 2007

- Gortner, R. A.; Hoffman, W. F. (1925). "l-Cystine". Organic Syntheses. 5: 39.

- Aslaksena, M.A.; Romarheima, O.H.; Storebakkena, T.; Skrede, A. (28 June 2006). "Evaluation of content and digestibility of disulfide bonds and free thiols in unextruded and extruded diets containing fish meal and soybean protein sources". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 128 (3–4): 320–330. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.11.008.

- Gahl, William A.; Thoene, Jess G.; Schneider, Jerry A. (2002). "Cystinosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020552. PMID 12110740.

External links