Léonard Autié

Léonard-Alexis Autié, also Autier[2] (c. 1751 – 20 March 1820), often referred to simply as Monsieur Léonard, was the favourite hairdresser of Queen Marie Antoinette and in 1788–1789 founded the Théâtre de Monsieur,[3] "the first resident theatre in France to produce a year-round repertory of Italian opera."[4]

.jpg)

Early life and career as a hairdresser

Born in the medieval town of Pamiers in southwestern France, he was the son of Alexis Autié and Catherine Fournier, who were domestic servants. He spent time in Bordeaux, where he began to work as a hairdresser.[5]

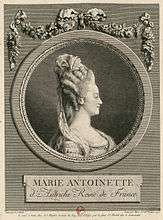

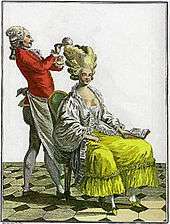

In 1769 he moved to Paris, where he began styling the hair of Julie Niébert, an actress at the Théâtre de Nicolet.[6] His unusual hairstyles immediately attracted attention, and he was soon styling the hair of women of the nobility, including Madame du Barry, Louis XV's mistress[7] and the Marquise de Langeac, a lady-in-waiting to the Dauphine Marie-Antoinette. By 1772 he had become the hairstylist of the Dauphine herself.[8]

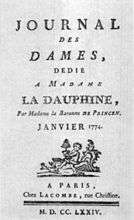

In January 1774, at the request of Marie Antoinette, Autié and Rose Bertin (her dressmaker) resuscitated the French fashion magazine, the Journal des Dames. The princess funded the venture, and the financially desperate Baroness de Prinzen agreed to lend her name to the project as the "managing editor". Needless to say, the very first issue was highly laudatory of the Dauphine's dress and hair styles. It also featured a new hairstyle invented by Mademoiselle Bertin, the ques-a-co ("What is it?"), consisting of three feathers at the back of the head, forming something similar to a question mark. Soon it was worn by all the princesses at court, and even by the king's mistress Madame du Barry. Although Léonard and Rose were "like two good sisters", Léonard could not help feeling a bit jealous, and before long he invented the pouf, which was first worn in April 1774 by the Duchess of Chartres, but was soon adopted by Marie-Antoinette, who made it very popular.[9]

Journal des Dames, 1774

Journal des Dames, 1774

Autié's success allowed him to establish a hair-dressing school and studio, the Académie de coiffeur ("a virtual House of Léonard"),[12] which was eventually situated in the rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin in Paris. He was joined in this enterprise by his two brothers, Pierre and Jean-François. Jean-François and their cousin Villanou also worked as hairdressers in the household of Marie-Antoinette, while Pierre worked for the king's sister, Madame Elizabeth. Taking advantage of their brother's fame, Pierre and Jean-François also used the name Léonard, creating much confusion for subsequent historians.[13]

By 1787 Léonard-Alexis had accumulated sufficient wealth that he no longer needed to dress hair for a living. He was still called Coiffeur de la Reine (Hairdresser to the Queen) and dressed Marie Antoinette's hair on commission for special occasions, such as galas and balls. His youngest brother, Jean-François, was responsible for dressing her hair on a daily basis and also took over as the head of the Académie de coiffure.[14]

Théâtre de Monsieur

Marie Antoinette was very fond of opera, especially Italian opera. She had supported the efforts of Jacques de Vismes du Valgay, director of the Royal Academy of Music (Paris Opera), to produce Italian operas on numerous occasions from June 1778 to March 1780,[15] and also those of Mademoiselle Montansier, director of the Théâtre de Versailles, to import the Italian troupe of the King's Theatre, London, for a successful season of opera buffa in the late summer of 1787.[16]

With Marie Antoinette's encouragement Léonard soon began a new career as an opera impresario. Not having sufficient capital, he formed a partnership with Montansier, who provided 100,000 livres for the enterprise.[17] The responsibility of being a royal patron of theatre traditionally fell to the elder of the reigning king's younger brothers, who was referred to as Monsieur. The Count of Provence (the future Louis XVIII) was not particularly interested in opera and did not fund the new theatre or participate in any direct way, but he did allow his name to be used. Thus the new theatre was to be called the Théâtre de Monsieur. However, Montansier and Léonard soon had a major disagreement. Léonard was very ambitious and wanted to present four genres: French opera, Italian opera, French plays, and Vaudevilles à caractères, whereas Montansier wanted to focus on Italian opera and the formation of a permanent troupe of first-rate Italian singers. She finally agreed to withdraw, but only if she was repaid her entire investment of 100,000 livres and an annuity of 20,000 livres per year for life. Léonard turned to the Italian violinist Giovanni Viotti, who was also in the service of Marie Antoinette. Viotti was able to provide some money, but not the entire amount. Léonard and Viotti finally persuaded Montansier to accept 40,000 livres plus the annuity. She would later open her own theatre in Paris to compete with the Théâtre de Monsieur.[17]

By 7 April 1788 Autié had been given sole ownership of the privilège to operate the theatre, with a term of 30 years.[18] On 28 May a society of investors was formed, with a board of directors mainly composed of lawyers and notaries.[19] On 18 June The Times of London reported "Parisian Intelligence, Paris 9 June. Leonard, the Queen's hairdresser, has obtained the patent for the comic Opera-House which is going to be erected at the Luxembourg. Cherubini and Viotti are to be the ostensible managers."[20] In fact, the Luxembourg Garden was considered as a site for the new theatre, but the Théâtre des Tuileries was the one finally selected. The Italian composer Luigi Cherubini was not immediately involved but joined the enterprise later. The Théâtre de Monsieur opened on 26 January 1789 and was successful with audiences. It earned the distinction of being the first French theatre to produce Italian opera on a year-round basis. Expenses seemed always to exceed the receipts, and soon Léonard was in even more financial difficulty, but it was other events beyond his control that were to prove more critical to his eventual withdrawal from the project.[21]

French Revolution and after

In June 1791, his brother Jean-François Autié accompanied the Duke de Choiseul during the royal family's flight to Varennes. After the royal family's arrest, Jean-François went abroad and was joined there by Leónard-Alexis. After three months, Léonard-Alexis returned to Paris. As the Revolution progressed and the situation for those associated with Marie Antoinette deteriorated, Léonard-Alexis left France again (probably in late June 1792) and eventually went to Russia. Jean-François remained in France and, due to his involvement in the flight to Varennes, was guillotined on 25 July 1794. Léonard-Alexis did not return to France until 1814, after Louis XVIII was restored to the throne.[22]

Léonard-Alexis Autié died in Paris.[23]

Personal life

Léonard-Alexis Autié married in Paris around 1779, and on 13 September 1781 his daughter Marie Anne Elisabeth was baptized at the Church of Saint-Eustache. The baptismal document identifies his wife as Marie Louise Adélaïde Jacobie Malacrida, who was the daughter of Jacques Malacrida, an officier de bouche (kitchen assistant) for the Count of Artois. A second daughter, Louise Françoise Alexandrine, was born on 6 January 1786 and baptized on 8 January with Jean-François Autié acting as her godfather and her maternal grandmother, Louise Catherine Malacrida, as her godmother.[24] A third daughter, Fanny, was born around 1789, and a son, Auguste–Marie, on 27 November 1790.[25] When Léonard-Alexis emigrated, his wife refused to follow and obtained a divorce on 29 messidor an II (17 July 1794).[26] When he died in 1820, he did not leave a will, and his two surviving children, Alexandrine and Fanny shared 716 francs and a small collection of jewels, the most important of which was a brooch, a bird of paradise valued at 3 francs, which he is presumed to have received for his services to Marie Antoinette.[27]

Memoirs

His supposed memoirs were published posthumously in 1838 by Alphonse Levavaseur in Paris as Souvenirs de Léonard, coiffeur de la reine Marie-Antoinette. The authenticity of this book is disputed: its actual authorship has been attributed to Louis-François L'Héritier[28] or Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon.[29]

See also

- Le Sieur Beaulard

References

Notes

- Bashor 2013, p. 5.

- Di Profio 2003, pp. 43, 534. Babeau 1895, p. 47, gives his surname as Antier. Some sources give his name as Jean-François Autié, a confusion with his youngest brother, also a coiffeur in the atelier Léonard, who died under the guillotine on 7 thermidor an II (25 July 1794); see Péricaud 1908, pp. 4–6; M., "Léonard, le coiffeur de Marie-Antoinette, a-t-il été exécuté ?", columns 291–293 in Duprat 1905, no. 1086 (30 August); and Bord 1909. For countervailing opinion, see Lenôtre 1905, pp. 287, 281, and Arthur Pougin, columns 396–399 in Duprat 1905, no. 1088 (20 September).

- Autié's privilège for the Théâtre de Monsieur commenced on 7 April 1788 and was valid for 30 years (Di Profio 2003, p. 43; Lister 2009, p. 126); the inaugural performance was given on 26 January 1789 (Di Profio 2003, p. 75; Lister 2009, p. 130).

- Lister 2009, p. 130.

- Bashor 2013, pp. VII, 5–6.

- Bashor 2013, pp. 2, 9.

- Bashor 2013 pp 29ff

- Bashor 2013, pp. 39–44.

- Bashor 2013, pp. 63–69.

- Bashor 2013, p. 64.

- Bashor 2013, p. 68.

- Bashor 2013, p. 49.

- Bashor 2013, p. 49; see also Vuaflart 1916, pp. 306–308.

- Bashor 2013, p. 112.

- Di Profio 2003, pp. 22–28.

- Di Profio 2003, pp. 31–35; Lister 2009, p. 125.

- Péricaud 1909, pp. 8–9; Bashor 2013, pp. 115–116; Lister 2009, pp. 125–127.

- Lister 2009, p. 126. Di Profio 2003, p. 43, calls it a brevet.

- Lister 2009, p. 126. Di Profio 2003, p. 43, notes: "Ce document, malheureusement en très mauvais état, est conservé en F-Pan [French National Archives, Paris], fonds du Minutier central : ET/CXVI/570."

- Quoted by Lister 2013, p. 126.

- Lister 2009, pp. 126, 130, 154–156; Bashor 2013, pp. 116–121.

- Tackett 2003, pp. 59, 68, 71, 264; Vuaflart 1916, pp. 305–307; letter from Léonard Autié to Louis XVIII (3 December 1817), reproduced in Bord 1909, pp. 201–205.

- Bashor 2013, p. X.

- Bord 1909, pp. 49–50.

- Bord 1909, p. 53.

- Bord 1909, p. 54.

- Bord 1909, p. 58.

- Bord 1909, p. 65.

- OCLC 28902173.

Sources

- Autié, Léonard [authorship disputed] (1838). Souvenirs de Léonard, coiffeur de la reine Marie-Antoinette. Paris: Alphonse Levavaseur. OCLC 28902173.

- Babeau, Albert (1895). Le théâtre des Tuileries sous Louis XIV, Louis XV et Louis VI. Paris: Sociét´de l'Histoire de Paris. View via Google Books.

- Bashor, Will (2013). Marie Antoinette's Head: The Royal Hairdresser, the Queen, and the Revolution. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. ISBN 9780762791538.

- Bord, Gustave (1909). La Fin de deux légendes. L'affaire Léonard. Paris: H. Dragon. View via Google Books.

- Di Profio, Alessandro (2003). La révolution des Bouffons : L'opéra italien au Théâtre de Monsieur 1789–1792. Paris: CNRS Editions. ISBN 9782271060174.

- Author unknown. Title unknown, L'intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 41st year (via Google Books). Paris, 1905.

- Fayolle; Michaud jeune (1842). "Léonard" in Michaud 1842, p. 323.

- Lenôtre, G. [pseudonym of Théodore Gosselin] (1905). Le Drame de Varennes. Paris: Perrin. View via Google Books.

- Lister, Warwick (2009). Amico: The Life of Giovanni Battista Viotti Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195372403.

- Michaud, Joseph-François, editor (1842). Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne, supplement, vol. 71. Paris: Michaud. View via Google Books.

- Péricaud, Louis (1908). Théâtre de "Monsieur " Paris: Jorel. View via Google Books.

- Tackett, Timothy (2003). When the King Took Flight. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674010543.

- Vuaflart, Albert (1916). La maison du comte de Fersen, rue Matignon. La journée du 20 juin 1791 – Monsieur Léonard. Paris. Copy via Gallica.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Léonard-Alexis Autié. |

- Souvenirs de Léonard, coiffeur de la reine Marie-Antoinette. In two volumes (1838) at Gallica.

- Recollections of Léonard, Hairdresser to Queen Marie-Antoinette, translated from the French by E. Jules Méras. 1909 edition at Google Books. 1912 edition at Internet Archive.

- Marie Antoinette's Head: The Royal Hairdresser, the Queen, and the Revolution by Will Bashor (2013) – Lyons Press page