Kullervo

Kullervo is an ill-fated character in the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot.

Growing up in the aftermath of the massacre of his entire tribe, he comes to realise that the same people who had brought him up, the tribe of Untamo, were also the ones who had slain his family. As a child, he is sold into slavery and mocked and tormented further. When he finally runs away from his masters, he discovers surviving members of his family, only to lose them again. He seduces a girl who turns out to be his own sister, having thought his sister dead. When she finds out it was her own brother who seduced her, she commits suicide. Kullervo becomes mad with rage, returns to Untamo and his tribe, destroys them using his magical powers, and commits suicide.

At the end of the poem the old sage Väinämöinen warns all parents against treating their children too harshly.

Story

The story of Kullervo is laid out in runes (chapters) 31 through 36 of the Kalevala.

Rune 31 – Kullervo, son of Evil

Untamo is jealous of his brother Kalervo, and the strife between the brothers is fed by numerous petty disputes. Eventually Untamo's resentment turns into open warfare, and he kills all of Kalervo's tribe save for one pregnant girl called Untamala, whom Untamo enslaves as his maid. Shortly afterwards, Untamala gives birth to a baby boy she names Kullervo.

When Kullervo is three months old, he can be heard vowing revenge and destruction upon Untamo's tribe. Untamo attempts to kill Kullervo three times (by drowning, fire, and hanging). Each time, the infant Kullervo is saved by his latent magical powers.

Untamo allows the child to grow up, then tries three times to find employment for him as a servant in his household, but all three attempts fail as Kullervo's wanton and wild nature makes him unfit for any domestic task. In the end, Untamo decides to rid himself of the problem by selling Kullervo to Ilmarinen as a slave.[1][2]

Rune 32 – Kullervo as a shepherd

The boy is raised in isolation because of his status as a slave, his fierce temper, and because people fear his growing magical skills. The only memento that the boy retains from his previous life in a loving family is an old knife that'd been passed along with him as an infant.

Pohjan Neito/Tytär (Maiden/Daughter of the North), wife of Ilmarinen, enjoys tormenting the slave boy, now a youth, and sends Kullervo out to herd her cows with a loaf of bread with stones baked into it. This chapter includes a lengthy magical poem invoking various deities to grant their protection over the herd and to keep the owners prosperous.[1]

Rune 33 – Kullervo and the cheat-cake

Kullervo sits down to eat, but his beloved heirloom knife breaks on one of the stones in the bread. Kullervo is overwhelmed with rage. He drives the cows away to the fields, then summons up bears and wolves from the woods, making them appear like cows instead. He herds these to Ilmarinen's house and tells the wicked mistress of the house to milk them, upon which they turn back into wolves and bears and maul her. As she lies there bleeding, she invokes the high god Ukko to kill Kullervo with a magic arrow, but Kullervo prays for the spell to kill her instead for her wickedness, which it indeed does.[1]

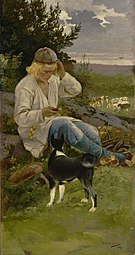

Kullervo with His Herds, Sigfrid Keinänen, 1896

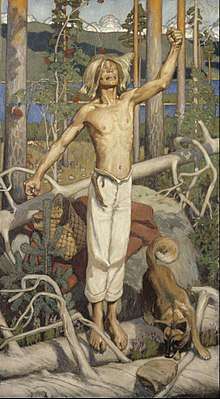

Kullervo with His Herds, Sigfrid Keinänen, 1896 Kullervo herding his wild Flocks, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1917

Kullervo herding his wild Flocks, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1917

Rune 34 – Kullervo finds his tribe

Kullervo then flees from slavery and finds that his family is actually still alive except for his sister, who has disappeared and is feared dead.

Rune 35 – Kullervo's deeds

Kullervo's father has no more success than Untamo in finding work suited for his son, and thus sends the young man to collect taxes due to his tribe. On his way back home in his sleigh, Kullervo propositions several girls he sees on the way: all of them reject him. Finally, he meets a beggar-girl who also rejects him at first, struggling and screaming when he pulls her into his sleigh. But he starts talking to her sweetly and shows her all the gold he's collected during his trip, bribing her into sleeping with him. Afterwards, she asks who he is, and as she realises he's her own brother, she commits suicide by throwing herself into the rapidly rushing river nearby. The distraught Kullervo returns to his family and tells his mother what happened.[1]

Rune 36 – Kullervo's victory and suicide

Kullervo vows revenge on Untamo. One by one, his family members try to dissuade him from the fruitless path of evil and revenge. His mother asks what will become of her and Kullervo's father in their old age, and what will become of Kullervo's siblings if he's not there to take care of them, but Kullervo only replies that they can all die for all he cares—all he cares about is revenge. As he leaves, he asks if his father, brother and sister will mourn him if he dies, but they say they won't—that they'd rather wait for a better son and brother to be born who is not so full of wickedness. Finally, Kullervo asks his mother if she'll weep for him, and she replies that she will, even if she knows him to be wrong. Kullervo hardens his heart and refuses to reconsider, and goes to war full of haughty pride, singing and playing his horn.

He becomes so obsessed with his revenge that even as he learns of the deaths of his family members during his journey, he doesn't even stop to honour their deaths, apart from weeping a little for his mother—yet he does not pause in his quest for revenge. He prays to the high god Ukko to get from him a magical broadsword, which he then uses to slay Untamo and his tribe, sparing no one, burning down his entire village.

When he returns home, he finds the dead bodies of his own family littered about the estate. His mother's ghost speaks to him from her grave and advises him to take his dog and go to the wild woods for shelter. He does so, but instead of finding shelter, he only discovers the place by the river where he'd seduced his sister, the earth still mourning out loud of his ruining of her: no plants grow in the spot where he'd slept with her, either.

Kullervo then asks of Ukko's sword if it will have his life. The sword eagerly accepts, noting that as a weapon it doesn't care whose blood it drinks—it's drunk both innocent and guilty blood before. Kullervo commits suicide by throwing himself on his sword. On hearing the news, Väinämöinen comments that children should never be given away or ill-treated in their upbringing, lest like Kullervo they grow wicked and bereft of wisdom or honour.[1]

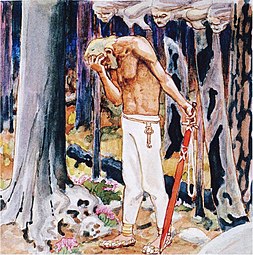

Regretful Kullervo, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1918

Regretful Kullervo, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1918 Kullervo Speaks to His Sword, Carl Eneas Sjöstrand, 1868, cast into bronze in 1932

Kullervo Speaks to His Sword, Carl Eneas Sjöstrand, 1868, cast into bronze in 1932

Evaluation

Kullervo is fairly ordinary in Finnish mythology, in being a naturally talented magician; however, he is the only irredeemably tragic example. He showed great potential, but being raised badly, he became an ignorant, implacable, immoral and vengeful man.

The death poem of Kullervo in which he, like Macbeth, interrogates his blade, is famous. Unlike the dagger in Macbeth, Kullervo's sword replies, bursting into song: it affirms that if it gladly participated in his other foul deeds, it would gladly drink of his blood also. This interrogation has been duplicated in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Children of Húrin with Túrin Turambar talking to his black sword, Gurthang, before committing suicide. (Túrin also, like Kullervo, unwittingly fell in love with his own sister and was devastated when he learned the truth, his sister also killing herself).[3]

Some literary critics have suggested that Kullervo's character is a bitter metaphorical representation of Finland's frequent struggles for independence. Certainly Jääkärimarssi (Jäger March), a well-known Finnish military march, contains lines me nousemme kostona Kullervon/soma on sodan kohtalot koittaa (We arise like the wrath of Kullervo/so sweet are the fates of war to undergo).

The story of Kullervo is unique among ancient myths in its realistic depiction of the effects of child abuse.[4] The canto 36 ends in Väinämöinen stating that an abused child will never attain the healthy state of mind even as adult, but will grow up as a very disturbed person.

Wainamoinen, ancient minstrel,

As he hears the tidings,

Learns the death of fell Kullervo,

Speaks these words of ancient wisdom:

"O, ye many unborn nations,

Never evil nurse your children,

Never give them out to strangers,

Never trust them to the foolish!

If the child is not well nurtured,

Is not rocked and led uprightly,

Though he grow to years of manhood,

Bear a strong and shapely body,

He will never know discretion,

Never eat the bread of honor,

Never drink the cup of wisdom."

"Kullervo" from Kalevala,

Translation by John Martin Crawford[5]

- Silloin vanha Väinämöinen,

- kunpa kuuli kuolleheksi,

- Kullervon kaonneheksi,

- sanan virkkoi, noin nimesi:

- "Elkötte, etinen kansa,

- lasta kaltoin kasvatelko

- luona tuhman tuuittajan,

- vierahan väsyttelijän!

- Lapsi kaltoin kasvattama,

- poika tuhmin tuuittama

- ei tule älyämähän,

- miehen mieltä ottamahan,

- vaikka vanhaksi eläisi,

- varreltansa vahvistuisi.".[6]

In art

Kullervo is an eponymous 1860 play by Aleksis Kivi.[1] An English translation, by Douglas Robinson, was published in 1993: Aleksis Kivi's Heath Cobblers and Kullervo.

Kullervo is an eponymous 1892 choral symphony in five movements for full orchestra, two vocal soloists, and male choir by Jean Sibelius. It was opus 7 for Sibelius and his first successful work.[1]

Kullervo's Curse (1899) and Kullervo Rides to War (1901) are two paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela on the myth.[1]

In the Jäger March (Jääkärin marssi) by Jean Sibelius one of the lines reads: Me nousemme kostona Kullervon, in English: We shall rise as Kullervo's revenge.[7]

Kullervo is the subject of a 1988 opera by Aulis Sallinen.[1]

Kullervo is also the subject of a brief symphonic poem composed in 1913 by Leevi Madetoja.[1]

In 2006, the Finnish metal band Amorphis released the album Eclipse, which tells the story of Kullervo according to a play by Paavo Haavikko. The play has been translated into English by Anselm Hollo.[8]

The Hilliard Ensemble commissioned an English language setting of Kullervo's story, Kullervo's Message, from Veljo Tormis.[9]

Influence on J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien wrote an interpretation of the Kullervo cycle in 1914; the piece was finally published in its unfinished form as The Story of Kullervo[10] in 2010. The published version was edited by Verlyn Flieger and was originally published in Tolkien Studies. It was re-published in book form in 2015 by HarperCollins. It was his first attempt at writing an epic narrative but was never completed.[10] The story acted as a seed for the epic tale of Túrin Turambar which features in The Silmarillion, the "Narn i Chîn Húrin" section of Unfinished Tales and, in a longer form, The Children of Húrin as well as the poem "The Lay of the Children of Húrin".[3][11][12][13]

References

- Asplund, Anneli (13 October 2004). "Kullervo". Kansallisbiografia. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Kullervo Kalervon poika". Sammon Salat. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Graham, Elizabeth (10 April 2016). "Frodo, Bilbo, Kullervo: Tolkien's Finnish Adventure". NPR. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "www.finlit.fi". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- "Translation by John Martin Crawford". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Kalevala". www.finlit.fi. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Lehtonen, Tiina-Maija (9 January 2018). "Jean Sibelius - vaarallisen Jääkärimarssin säveltäjä". Yle. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Siltanen, Vesa (15 February 2016). "Uuden alun kynnyksellä 10 vuotta sitten – Amorphis-miehet muistelevat Eclipsen syntyä". Soundi. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Evans, Rian (30 May 2008). "Hilliard Ensemble". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Tolkienin Kalevala-tarina julkaistaan sadan vuoden viipeellä – Kullervo vannoo kostoa taikuri-Untamolle" [Tolkien's Kalevala story published after a hundred-year lag – Kullervo vows revenge on Untamo the magician] (in Finnish). Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- Sander, Hannah (27 August 2015). "Kullervo: Tolkien's fascination with Finland". BBC. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "JRR Tolkien: 'Dark' unfinished tale Kullervo published". BBC. 27 August 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Tapiola, Paula (27 August 2015). "J.R.R. Tolkienin Kullervo-tarina julkaistu – "Kaikista tummin tarina"". Yle. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

External links

- John Martin Crawford's English translation of the Kalevala (1888). Hosted at Sacred Texts

- Tolkien's first fantasy novel