Cryolite

Cryolite (Na3AlF6, sodium hexafluoroaluminate) is an uncommon mineral identified with the once-large deposit at Ivittuut on the west coast of Greenland, depleted by 1987.

| Cryolite | |

|---|---|

Cryolite from Ivigtut Greenland | |

| General | |

| Category | Halide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Na3AlF6 |

| Strunz classification | 3.CB.15 |

| Dana classification | 11.6.1.1 |

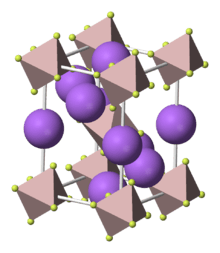

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/n |

| Unit cell | a = 7.7564(3) Å, b = 5.5959(2) Å, c = 5.4024(2) Å; β = 90.18°; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 209.9 g mol−1 |

| Color | Colorless to white, also brownish, reddish and rarely black |

| Crystal habit | Usually massive, coarsely granular. The rare crystals are equant and pseudocubic |

| Twinning | Very common, often repeated or polysynthetic with simultaneous occurrence of several twin laws |

| Cleavage | None observed |

| Fracture | Uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 2.5 to 3 |

| Luster | Vitreous to greasy, pearly on {001} |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.95 to 3.0. |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.3385–1.339, nβ = 1.3389–1.339, nγ = 1.3396–1.34 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.001 |

| 2V angle | 43° |

| Dispersion | r < v |

| Melting point | 1012 °C |

| Solubility | Soluble in AlCl3 solution, soluble in H2SO4 with the evolution of HF, which is poisonous. Insoluble in water.[1] |

| Other characteristics | Weakly thermoluminescent. Small clear fragments become nearly invisible when placed in water, since its refractive index is close to that of water. May fluoresce intense yellow under SWUV, with yellow phosphorescence, and pale yellow phosphorescence under LWUV. Not radioactive. |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6] |

Due to its rarity it is possibly the only mineral on Earth ever to be mined to commercial extinction.[7]

History

Cryolite was first described in 1798 by Danish veterinarian and physician Peder Christian Abildgaard (1740–1801);[8][9] it was obtained from a deposit of it in Ivigtut and nearby Arsuk Fjord, Southwest Greenland. The name is derived from the Greek language words κρύος (cryos) = frost, and λίθος (lithos) = stone.[10] The Pennsylvania Salt Manufacturing Company used large amounts of cryolite to make caustic soda at its Natrona, Pennsylvania works, and at its Cornwells Heights, Pennsylvania, Plant, during the 19th and 20th centuries.

It was historically used as an ore of aluminium and later in the electrolytic processing of the aluminium-rich oxide ore bauxite (itself a combination of aluminium oxide minerals such as gibbsite, boehmite and diaspore). The difficulty of separating aluminium from oxygen in the oxide ores was overcome by the use of cryolite as a flux to dissolve the oxide mineral(s). Pure cryolite itself melts at 1012 °C (1285 K), and it can dissolve the aluminium oxides sufficiently well to allow easy extraction of the aluminium by electrolysis. Substantial energy is still needed for both heating the materials and the electrolysis, but it is much more energy-efficient than melting the oxides themselves. As natural cryolite is too rare to be used for this purpose, synthetic sodium aluminium fluoride is produced from the common mineral fluorite.

Source locations

Besides Ivittuut, cryolite has also been reported at Pikes Peak, Colorado; Mont Saint-Hilaire, Quebec; and at Miass, Russia. It is also known in small quantities in Brazil, the Czech Republic, Namibia, Norway, Ukraine, and several U.S. states.

Uses

Molten cryolite is used as a solvent for aluminium oxide (Al2O3) in the Hall–Héroult process, used in the refining of aluminium. It decreases the melting point of molten (liquid state) aluminium oxide from 2000–2500 °C to 900–1000 °C, and and increases its conductivity thus making the extraction of aluminium more economical.

Cryolite is used as an insecticide and a pesticide.[11] It is also used to give fireworks a yellow color.[12]

Physical properties

Cryolite occurs as glassy, colorless, white-reddish to gray-black prismatic monoclinic crystals. It has a Mohs hardness of 2.5 to 3 and a specific gravity of about 2.95 to 3.0. It is translucent to transparent with a very low refractive index of about 1.34, which is very close to that of water; thus if immersed in water, cryolite becomes essentially invisible.[6]

References

- CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 83rd Ed., p. 4-84.

- Gaines, Richard V., et al (1997) Dana's New Mineralogy, Wiley, 8th, ISBN 978-0-471-19310-4

- Cryolite: Cryolite mineral information and data. Mindat.org (2010-10-03). Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- Cryolite Mineral Data. Webmineral.com. Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- Cryolite, Handbook of Mineralogy. Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, Manual of Mineralogy, 20th ed., John Wiley and Sons, New York ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- "Royal Society of Chemistry, Chemistry in its element: compounds - Cryolite". Archived from the original on 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- Abildgaard (1799). "Norwegische Titanerze und andre neue Fossilien" [Norwegian titanium ores and other new fossils [i.e., anything dug out of the earth])]. Allgemeines Journal der Chemie (in Danish). Leipzig. 2: 502.

In der ordentlichen Versammlung der königl. Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften am 1. Februar dieses Jahres stattete Hr. Prof. Abildgaard einen Bericht über die Norwegischen Titanerze und über die von ihm mit denselben angestellten Analysen ab. Zugleich theilte er auch eine Nachricht von einer vor wenigen Jahren aus Grönland nach Dänemark gebrachten besonders weißen spathartigen Miner mit. Einer damit angestellten Untersuchung zu folge bestand sie aus Thonerde und Flußspathsäure. Eine Verbindung, von welcher noch kein ähnliches Beyspiel im Mineralreich vorgekommen ist. Sie hat den Namen Chryolit erhalten, weil sie vor dem Löthrohre wie gefrorne Salzlauge schmilzt.

(At the ordinary session of the [Danish] Royal Society of Science on February 1st of this year, Prof. Abildgaard presented a report about Norwegian titanium ores and about the analysis of them undertaken by him. He also communicated a notice of an especially white, spar-like mineral that was brought several years ago from Greenland to Denmark. According to an investigation performed on it, it consists of alumina and hydrofluoric acid. A compound of which no similar example in the mineral realm has yet been found. It received the name "cryolite" because under a blowpipe, it melts like frozen brine.) - Abildgaard, P. C. (1800). Om Norske Titanertser og om en nye Steenart fra Grönland, som bestaaer af Flusspatsyre og Alunjord [On Norwegian titanium ores and on a new mineral from Greenland, which consists of hydrofluoric acid and alumina]. 3rd (in Danish). 1. Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabers-Selskabs (The Royal Danish Scientific Society). pp. 305–316.

Han har kaldt denne grönlandske Steen Kryolith eller Iissteen formedelst dens Udseende, og fordi den smelter saa meget let for Blæsröret.

(He has named this Greenlandic stone cryolite or ice stone on account of its appearance, and because it melts so easily under a blowpipe.) - Albert Huntington Chester, A Dictionary of the Names of Minerals Including Their History and Etymology (New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1896), p. 68.

- EPA R.E.D. FACTS Cryolite http://www.epa.gov/oppsrrd1/REDs/factsheets/0087fact.pdf

- Helmenstine, Anne Marie. "How Firework Colors Work and the Chemicals That Make Vivid Colors". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2019-09-01.