Rod (Slavic religion)

Rod (Polish, Slovenian, Croatian: Rod, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Serbian Cyrillic: Род, Ukrainian Cyrillic: Рід) – in the pre-Christian religion of Eastern and Southern Slavs god of family, ancestors and fate, perhaps supreme god. Among Southern Slavs also known as Sud ("Judge") and Prabog (Pre-God).[1] Usually mentioned together with rozhanitsy (at South Slavs sudzenitsy).

| Rod | |

|---|---|

Ancestors, fate, spiritual continuity, family continuity | |

Anthropomorphic representation of Rod in a temple of the Native Ukrainian National Faith. | |

| Abode | Vyraj |

| Symbol | Rosette |

| Consort | Rozhanitsa |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek equivalent | Zeus |

| Roman equivalent | Quirinus |

| Celtic equivalent | Toutatis |

| Baltic equivalent | Dievas |

Rod is an indirect, Slavic successor of the Indo-European god *Dyeus, who was "Lord of Gods", "Lord of Heaven", "King of Gods". First haircut (postriziny) was dedicated to him, where he and rozhanitsy were given a meal and cut hair.[2] His cult lost its importance and in the ninth or tenth century he was replaced by Perun, Svarog and/or Svetevid, which would explain his absence in the pantheon of Vladimir the Great.[3][4][5]

Name

Rod's name is confirmed in Old Church Slavonic and Old East Slavic sources about pre-Christian religion. The name is derived from the Proto-Slavic word *rodъ meaning "family", "birth", "harvest", "genus", "nature", and this word is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *wréh₂ds meaning "root". Aleksander Brückner also notes the similarity of the name to the Avestan word rada- - meaning "guardian", "keeper".[6]

In the early religion of the Slavs, the god of the sky was *Deiwos[7] or *Div,[8][7][9] but then he was replaced by Rod. *Deiwos was the same as the Proto-Indo-European *Dyeus (cf. Sanskrit Deva, Latin deus ("god"), Greek Zeus, Old High German Tiwaz, Lithuanian Dievs).[10] According to Jakobson, the Proto-Slavs and the Indo-Iranian peoples they bordered with made a "peculiar religious revolution." The Proto-Slavic peoples (together with the Iranian peoples) gave the Indo-European term *deiwos in the meaning of "god" and "divine", pejorative, demonic character (look Polish dziwny ("strange", "odd"), dziwożona, Zoroastrian daeva), replacing it with the term "bog" (from the Iranian baga), which also means "wealth" and "good", borrowing many other terms related to religion and spirituality from Iranian languages.[11][12] *Deiwos as the term "what is heavenly" has been replaced by *nebesa ("heavens"), originally a plural of *nebo ("sky") from the Iranian word *nabah originally meaning "cloud".[13][14]

Sources

The first source mentioning the Rod is the Word of St. Gregory Theologian about how pagans bowed to idols of the 11th century:[15]

This word also came to the Slavs, and they began to make sacrifices to Rod and rozhanitsy before Perun, their god. And earlier they sacrificed to ghosts (upyrí) and beregins. But also on the outskirts they pray to him, the cursed god Perun, and to Hors and Mokosh, and to the vila(s) - they do it secretly

Word of Chrystolubiec describes the prayers dedicated to the Rod and rozhanitsy:[16]

... and we mix some pure prayers with the cursed offering of idols, because they put an unlawful table in addition to a kutia table and a lawful dinner, designed for Rod and rozanitsy, causing God's anger

In a handwritten commentary on the Gospel from the 15th century, Rod defies Christian God as the creator of people:[17]

So not Rod sitting in the air, throwing clods to the ground, and from this children are born [...] because God is the creator, not Rod

The cult of Rod was still popular in the 16th-century Rus, as evidenced by penance given during confession by Orthodox priests described in the penitentiaries of Saint Sabbas of Storozhi[18]

Did you make offerings disgusting to God together with women, did you pray to the vilas, or did you in honor of Rod and rozhanitze, and Perun and Hors and Mokosh drink and eat: three years of fasting with obeisances

Krodo

The Saxon historian Helmold (c. 1125-1177) in the Chronica Slavorum writes that the Slavs believed in one God:[19]

But they do not deny that there is among the multiform godheads to whom they attribute plains and woods, sorrows and joys, one god in the heavens ruling over the others. They hold that he, the all powerful one, looks only after heavenly matters; that the others, discharging the duties assigned to them in obedience to him, proceeded from his blood; and that one excels another in the measure that he is nearer to this god of gods.

— Helmod, Chronica Slavorum

In the first millennium EC present-day northern and eastern Germany was inhabited by the Saxon and Veneti tribes along with other West Slavic tribes. The 15th-century Cronecken der Sassen written by Hermann Bote says that the Saxons worshiped a god named Krodo together with the Slavs.[20] In old records this name appears as Hrodo, Chrodo, Krodo or in Latinized form: Crodone. Bote also describes that Julius Caesar during the conquest of Germania ordered to build several fortresses topped with statues of Roman deities. In the place of Harzburg, where later the city of Bad Harzburg was founded in Lower Saxony, a statue of Saturn was supposed to be standing, whose local peoples were to worship as Krodo.[21]

During the Saxon Wars in 780, the Frankish king Charlemagne occupied the region, he destroyed the statue in the effort to Christianise the Saxon people:[21]

... King Charles came to the land and converted the East Saxons. Thus he spoke: Who is your God? Then the common folk cried: Krodo, Krodo is our God. Then King Charles said: Is Krodo your God? That is: The toad devil! ["toad" is kroden in Saxon, producing a word-play] Thereafter the word ["Krodo"] became a bad word among the Saxons. And then King Charles went to Harzburg and destroyed the idol Krodo, and laid down the cathedral in Saligenstidde, now Osterwieck, in honour of Saint Stephen.

— Hermann Bote, Cronecken der Sassen

The chronicle also mentions Krodo's iconography. The idol was supposed to be on a pole and be barefoot. He had four attributes that were supposed to represent the four elements:[21]

- Water – standing on fish

- Earth – bucket of flowers

- Fire – wheel as symbol of sun

- Air – fluttering linen belt

Bothe himself considered Krodo as the god of the Saxons – he was assigned to the Slavs first time by Georg Fabricius in 1597 in the posthumous Originum illustrissimae stirpis Saxonicae libri septem.[22]

Krodo is also mentioned by Widukind of Corvey – Saxon chronicler and Christian monk. He writes that the Saxons were to get a metal statue of Saturn from the Polabian Slavs.[23]

In the Cathedral of St. Simon and St. Jude (built in 1047), which was part of the Imperial Palace of Goslar, an altar was found, which in about 1600 was called Altar of Krodo. This altar was probably made in the 11th century and is entirely made of bronze. The altar is currently in the museum in Goslar.

Even in the nineteenth century by German researchers Krodo was considered the chief deity of the Slavs.[24] Modern scholars of Slavic mythology question the existence of Krodo.[22][25]

Cult

According to ethnologist Halyna Lozko, Rod's Holiday was celebrated on December 23[26] or according to Czech historian and archaeologist Naďa Profantová on December 26.[27] The Rod and rozhanitsy were offered bloodless sacrifices in the form of bread, honey, cheese and groat (kutia).[28][26] Before consuming kutia, the father of the family, who replaced the role of the volkhv or zhretsa, tossed the first spoon up into the holy corner. This custom exists in Ukraine to this day.[26] Then the feast began at a table in the shape of a trapeze.[28] After the feast, they make requests to Rod and rozhanitsy: "let all good things be born".[26]

In Rus, after Christianization, feasts dedicated to Rod were still practiced, as mentioned in the Word of Chrystolubiec.[16] In the first years of the existence of the Saint Sophia's Cathedral in Kiev pagans came to celebrate Koliada there, which was later severely punished. The remains of the Rod cult were to survive until the nineteenth century.[26]

Interpretations

Scholars opinions

Boris Rybakov

According to the concept presented by Boris Rybakov, Rod was originally the chief Slavic deity during the times of patriarchal agricultural societies in the first millennium CE,[29] later pushed to a lower position, which would explain his absence in the pantheon of deities worshiped by Vladimir the Great. Rybakov relied on the Word of St. Gregory Theologian..., where the Slavs first sacrificed to wraiths, then to Rod and rozhanitsy, and finally to Perun, which would reflect the alleged evolution of Slavic beliefs from animism through cult of natural forces to henoteism.[4][30] The sculpture known as Zbruch Idol was supposed to depict Rod as the main Slavic deity according to Rybakov's concept.[4]

Rybakov also believes that all the circles and spiral symbols represent the different hypostases of Rod. Such symbols are to be "six-petal rose inscribed in a circle" (rosette) (![]()

![]()

Leo Klejn and Mikola Zubov

These scholars criticized Rybakov's findings. In one of his works, Rybakov maintained that Perun could not be borrowed by the Vainakhs, since the supreme god of the Slavs was Rod, and Perun was introduced only by Vladimir as the druzhina patron. However, this is contradicted by the traces of Perun throughout Slavic territory. These researchers argue that it is necessary to identify traces of the original sources of texts and restore them to the historical context under which specific Old Russian texts were created. They believe that Old Russian authors, when describing Rod and rozhanitsy, used ready semantic blocks borrowed from other sources, mainly the Bible and writings of Greek theologians that were misinterpreted: in Byzantine Empire the horoscope was called "genealogy", which can literally be translated as "rodoslovo". Therefore, these researchers believe that the cult of Rod and parents did not exist in the pre-Christian religion of the Slavs. Zubov also believs that there was no extensive genealogy of the gods in the East Slav religion and Perun was the only god.[32][33]

Aleksander Gieysztor

Gieysztor considers Rod the god of social organization. After Benvenist he compares him to the Roman Quirinus, whose name comes from *covir or curia, which can be translated as "god of the community of husbands", to the Umbrian Vofionus, whose name contains a root similar to the Indo-European word *leudho, Anglo-Saxon leode ("people"), Slavic *ludie and Polish ludzie, and to the Celtic Toutatis, whose name derives from the Celtic core *teuta meaning "family", but rejects connecting Rod with Indian Rudra.[34]

Because of the function of fertility and wealth, he identifies with him the Belarusian Spor, whose name means "abundance", "multiplicity".[35]

Andrzej Szyjewski

According to Andrzej Szyjewski, Rod "personifies the ideas of family kinship as a symbol of spiritual continuity (rodoslovo)." Rod was also to direct the souls of the dead to Vyraj, and then send them back to our world in the form of clods of earth cast down or entrusted to nightjars and storks.[36]

Fyodor Kapitsa

According to the folklorist Fyodor Kapitsa, the cult of Rod and parents was almost completely forgotten over time. Rod transformed into a ghost - a patron of the family, a "home grandfather", and later a guardian of newborns and honoring ancestors. Traces of Rod's cult were mainly seen in everyday life. Remains of the Rod cult are to be Russian Orthodox holidays such as Day of the Dead (Holy Thursday) and Radonica (Tuesday of the first week after Easter) during which the dead are worshiped.

In the times of Kievan Rus in the 11th and 12th centuries, the cult of Rod was to be particularly important for princes because he was considered the patron of the unity of the clan, and the right to the throne and land of ancestors depended on it. Since fertility has always been associated with femininity, Rod's cult was traditionally feminine. Thus, female priestesses were associated with the cult of Rod, who were to sacrifice him or organize special feasts several times a year. Bread, porridge, cheese and honey were prepared for the feast, then such a meal was put in the shrines. It was believed that the gods appear there invisible to the human eye. Rod was sometimes called to protect people from illness, but rozhanitsy played a major role in this ritual.[37]

Oleg Kutarev

Kutarev notes the similarity between the cult of Rod and the cult of the South Slavic Stopan and the East Slavic Domovoy - all were given a meal, they were to manage the fate and were associated with the worship of ancestors.[38]

Viljo Mansikka

This Russian and Finnish philologist notes that sometimes in the Slavic languages the Greek term "τύχη" (týchi, "luck") is translated as rod, and "είμαρμένη" (eímarméni, "destiny") is translated as a rozhanitsa.[39]

Jan Máchal

This Czech slavist claimed that Rod was a god who represented male ancestors and rozhanitsy represented female ancestors.[40]

Halyna Lozko

According to Halynaa Losko, for Ukrainians Rod was god over the gods. He is the giver of life and was supposed to stay in heaven, ride on clouds and assign man his fate. Rod was the personification of the descendants of one ancestor, that is, he was associated with the entire family: dead ancestors, living people and unborn generations. Over time, Rod became a Domovoy whose figurines were owned by many families. Rod's and rozhanitsy images were also to appear on the rushnyks as motives of the tree of life. The 20th-century ethnographic finds show the door of huts with the image of a family tree: men were depicted on leaves and women on flowers of this tree. When someone was dying - a cross was drawn next to his name, when someone was being born - a new twig, leaf or flower was drawn.[26]

In popular culture

Rod is mentioned in the description of the story of the Pagan Online game, where the first continent created by Swarog is called Land of Rod.[42]

Polish folkstep band ROD.[43]

Rod is chief god of Balto-Slavic pantheon (Dievas) in Marvel Comics universe (List of deities in Marvel Comics).

The neopagan folk metal band Arkona dedicated an album to Rod, named Goi, Rode, Goi!.

Gallery

.jpg) "Chrodo" illustrated in L'Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures, by Bernard de Montfaucon, 1722.

"Chrodo" illustrated in L'Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures, by Bernard de Montfaucon, 1722..png) "Crodo" illustrated in Slavic mythology, by Andrey Kaisarov, 1804.

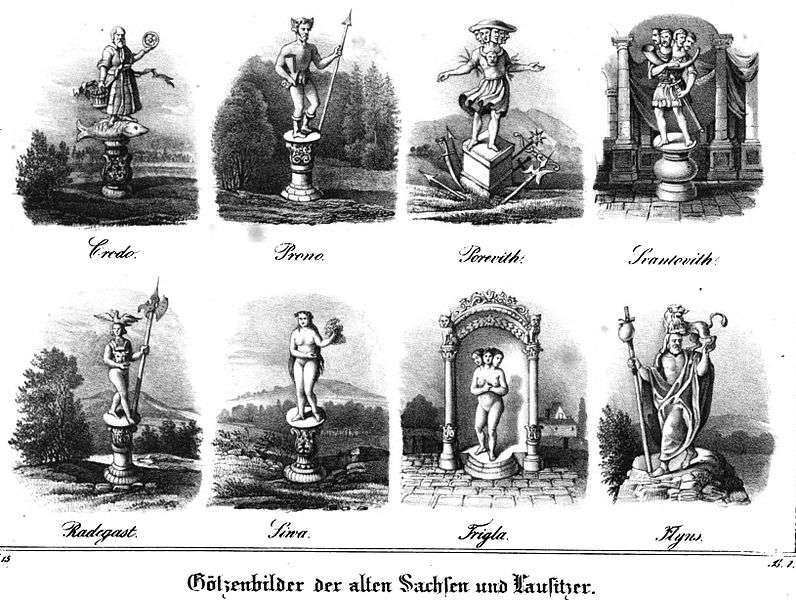

"Crodo" illustrated in Slavic mythology, by Andrey Kaisarov, 1804. "Crodo" featured first among illustrations of Slavo-Saxon deities, in Saxonia Museum für saechsische Vaterlandskunde, 1834.

"Crodo" featured first among illustrations of Slavo-Saxon deities, in Saxonia Museum für saechsische Vaterlandskunde, 1834.

References

- Mathieu-Colas, Michel. "Dieux slaves et baltes" (PDF).

- Szyjewski 2003, p. 193.

- Wilson 2015, p. 37.

- Strzelczyk 2007, p. 173-174.

- Szyjewski 2003, p. 192.

- Brückner 1985, p. 340.

- Rudy 2010, p. 4-5.

- "Proto-Indo-European Roots". tied.verbix.com. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- Pokorny 2005, p. 323.

- "Slavic religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 74.

- Rudy, p. 14-15.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 73-74.

- Rudy 2010, p. 14-15.

- Szyjewski 2003, p. 170.

- Brückner 1985, p. 170.

- Polakow 2017.

- Brückner 1985, p. 174.

- Helmud. "Kronika Słowian" (PDF).

- Christian Heinrich Delius (1826). "Untersuchungen über die Geschichte der Harzburg und den vermeinten Götzen Krodo". Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- Hanuš 1842, p. 90, 115-116, 119, 293,.

- Strzelczyk 2007, p. 100-101.

- Strzelczyk 2007, p. 101.

- Hanuš 1842, p. 116; "...Krodo, dem Slawen-Gotte, dem grossen Gotte...", tłum.: "...Krodo, Bóg Słowian, wielki Bóg...".

- Brückner 1985, p. 198.

- Losko 1997.

- Profantowa 2004, p. 192.

- Brückner 1985, p. 58.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 285.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 205.

- Ivanits 1989, p. 17.

- Andrey Beskov. "Язычество восточных славян. От древности к современности" (in Russian). Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Klejn 2004, p. 232-233.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 204-205.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 207.

- Szyjewski 2003, p. 192-193.

- Fyodor Kapitsa (2008). "Славянские традиционные праздники и ритуалы: справочник". Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- Oleg Kutarev (2013). "Характеристика Рода и Рожаниц в славянской мифологии: интерпретации Б. А. Рыбакова и его предшественников".

- Mansikka 2005.

- The Mythology of All Races (1918), Vol. III, Section "Slavic", Part I: The Genii, Chapter IV: Genii of Fate, pp. 249-252

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 65.

- "Step into the world of Pagan Online". Pagan Online. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- "Rod" (in Polish). karrot.pl. Retrieved 2019-07-26.

Bibliography

- Szyjewski, Andrzej (2003). Religia Słowian. ISBN 83-7318-205-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gieysztor, Aleksander (2006). Mitologia Słowian. ISBN 83-235-0234-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strzelczyk, Jerzy (2007). Mity, podania i wierzenia dawnych Słowian. ISBN 978-83-7301-973-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brückner, Aleksander (1985). Mitologia słowiańska. ISBN 8301062452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. ISBN 0765630885.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudy, Stephen (2010). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. ISBN 978-3110855463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Andrew (2015). The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation, Fourth Edition. ISBN 978-0300219654.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Polakow, Aleksander (2017). Русская история с древности до XVI века. ISBN 978-5040094677.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aitamurto, Kaarina (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. ISBN 978-1472460271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Losko, Halynaa (1997). Rodzima wiara ukraińska. ISBN 8385559264.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mansikka, Viljo Jan (2005). Религия восточных славян. ISBN 5920802383.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klejn, Leo (2004). Воскрешение Перуна. К реконструкции восточнославянского язычества. ISBN 5-8071-0153-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pokorny, Julius (2005). Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. ISBN 3-7720-0947-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Profantová, Naďa (2004). Encyklopedie slovanských bohů a mýtů. ISBN 8072772198.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). "Die wissenschaft des slawischen mythus im weitesten :den altpreussischlithauischen mythus mitumfassenden sinne. Nach quellen bear., sammt der literatur der slawisch-preussischlithauischen archäologie und mythologie" (in German). hdl:2027/umn.31951002357992g. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Evgeny Anichkov, Аничков Е.В. Язычество и Древняя Русь, 1914 [dostęp 2019-06-30].

- Christian Heinrich Delius, Untersuchungen über die Geschichte der Harzburg und den vermeinten Götzen Krodo, 1826 [dostęp 2019-06-30].