Kou Voravong

Kou Voravong (lao : ກຸ ວໍຣະວົງ) (6 December 1914 – 18 September 1954) was a Laotian politician. He was part of the anti-Japanese resistance leading group during the Second World War and after then anti-Lao Issara (ລາວອິດສລະ) in the post-war period. Throughout his career, from 1941 to 1954, he has been District Chief, Province Governor, member of the Lao National Assembly, and Lao Royal Government Minister.

Kou Voravong ກຸ ວໍຣະວົງ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Defense of Laos | |

| In office 21 November 1953 – 18 September 1954 | |

| Monarch | S.M. Sisavang Vong |

| Prime Minister | Prince Souvanna Phouma |

| Preceded by | Phoui Sananikone |

| Succeeded by | Prince Souvanna Phouma |

| Minister of the Interior and Cult of Laos | |

| In office 27 February 1950 – 15 October 1951 | |

| Prime Minister | Phoui Sananikone |

| Minister of Economic Affairs of Laos | |

| In office March 1948 – February 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Prince Boun Oum |

| Minister of Public Works and Justice of Laos | |

| In office 15 March 1947 – 24 March 1948 | |

| Prime Minister | Prince Souvannarath |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kou Voravong 6 December 1914 Savannakhet, Siam |

| Died | 18 September 1954 (aged 49) Vientiane, Kingdom of Laos |

| Nationality | Laotian |

| Political party | Phak Paxaathipatay |

The political crisis caused by his assassination, barely two months after the Geneva Agreements which prepared to restore peace in Indochina, contributed to bring down the current neutralist government (pro-French) which was replaced by a progressive one (pro-American) in extremely tense atmosphere of the Cold War between Russia and the United States. From 1955 indeed, the political history of this small landlocked country fell trapped inexorably in the ideological confrontation between the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union, annihilating any hope of national unification.

We can find a Kou Voravong Road in the city of Thakhek as well as in Savannakhet where his name is also given to an old stadium now a sports park. Since 1995, a statue is erected in the garden of the family residence where he lived as a child.

Family and childhood

Historical context

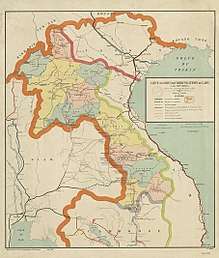

To counter the British Empire's expansion in this area, French colonies were established since the middle of the 19th century in Indochina. French Government also began from this period, to be interested in exploiting the Mekong River Valley's resources. Several expeditions later,[n 1] the King Oun Kham (ເຈົ້າອຸ່ນຄຳ) of Luang Prabang (ຫລວງພຣະບາງ), whose Kingdom was victim of neighboring countries covetousness attempting conquests (Siam, Myanmar, China) and at the same time divided by succession crisis, requested protection to France in 1887, accordingly to the explorer Auguste Pavie's advice. The Franco-Siamese Treaty dated October 3, 1893, determined new land-borders between Siam and Laos[n 2][1] and established the French Protectorate. The Lan Xang Kingdom (ຣາຊະອານາຈັກລ້ານຊ້າງ) was, therefore, administered by the French Colonial Government, already present in Cambodia, Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina.

The Laotian territory was then divided into provinces (khoueng - ແຂວງ),[n 3] including districts (muong - ເມືອງ), themselves regrouping cantons (baan - ບ້ານ). They were directed by local notables : chiefs (chao - ເຈົ້າ) who were intermediaries between local populations and French officials - « fonctionnaires d'autorité » - such as Government Commissioners - « commissaires de gouvernement » - and Residents of France - « résidents de France ». The Senior Resident - « le résident supérieur » - settled in Vientiane, which naturally became the country's administrative capital. All of these officials were assisted by some: adjoins (oupahaat - ອຸປະຮາດ), assistants (phousouei - ຜູ້ຊ່ວຍ) and secretaries (samien - ສະໝຽນ).[2]

In this historical context, Kou Voravong's maternal grandfather,[n 4] Phagna[n 5] Poui (ພຍາປຸ້ຍ), was appointed the first District Chief (chao muong - ເຈົ້າເມືອງ) of Khanthabouri (ຄັນທະບຸຣີ)[n 6] in 1902,[3] in Savannakhet Province, South-Laos. His younger brother, Thao[n 5] Taan Voravong (ທ້າວຕານ ວໍຣະວົງ) would succeed him from 1922 to 1928.

Birth and education

Born in this influential family in 1914 in Khanthabouri district, Kou Voravong was the only son[n 7] of Thaan-krou[n 5] Khammanh Nakphoumin (ທ່ານຄຣູຄຳໝັ້ນ ນັກພູມິນ) – schoolteacher, and Nang[n 5] Chanheuang (ນາງຈັນເຮືອງ), one of Phagna Poui's daughters. When his parents separated, he was adopted as infant by Nang Kiengkham (ນາງກຽງຄຳ), his mother's older sister, married to Thao Taan Voravong,[4] who was, at the time, interpreter at the « Résidence de France ». The couple didn't have any children.

Kou Voravong grew up in Savannakhet and pursued a primary education there. He obtained the « certificat d'études primaires complémentaire indochinois » - Certificate of Indochinese Additional Primary Studies - (CEPCI)[n 8] in 1930, went afterward to Vientiane and began his first-secondary-school year at the Collège[n 9] Auguste Pavie. But because of a conflict which opposed him to French Colonial administration,[n 10] his adopted father was sentenced to prison that same year. As reaction to this situation, Kou Voravong left school and returned to Savannakhet. As an out-of-school teenager, he practiced sports, especially soccer.[n 11]

One day, after a game, Kou Voravong and friends gathered some coconuts from trees bordering the playground to satisfy their thirst. Madame Malpuech, the previous Commissioner's wife shouted at them, considering these behaviors as an act of vandalism on public property. As captain, he defended his teammates with such virulence that she filed complaint with the police against him for assaulting.

_en_1925.jpg)

When the Resident of France in office[n 12] discovered that the young boy who stood up to him, was the son of Thao Taan Voravong, surprised by his educational background and particularly by his French language skills, he recruited him as private secretary (samien).

Kou Voravong left Savannakhet, returned to Secondary School, and while working, furthered his studies at the « École de droit et d'administration » (Law & Administration School), in Vientiane. He graduated in 1933, then occupied various administration positions. In 1941, he became adjoin (oupahaat) of the Governor (Deputy Chao Khoueng) of Vientiane. And in 1942, he was appointed District Chief (Chao Muang) of Paksane (ປາກຊັນ), in Borikhamxay Province (ບໍຣິຄຳຊັຍ)[5][6] at a time when the Empire of Japan, allied to Nazi Germany, was extending its high-handedness throughout the entire region.

Career

Anti-Japanese resistance

In Europe, the World War II broke out in 1939. As member of the Axis powers, Japan invaded Laos in 1941 with the French Vichy Government's agreement. On the other side, temporarily allied with the Japanese Empire in the «Greater Est Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere» – which back then reigned supreme on Southeast Asia – Siam Empire took advantage of France's defeat to annex Laotian territories of Champassak and Sayaboury,[n 13] both located on the east bank of the Mekong River.[1] From 1940 to 1945, the two Asian allies, as liberators involving indigenous populations and denouncing Western colonialism, encouraged rebellions. To counteract the Japan-Siamese ambitions, Admiral Jean Decoux, the « Gouverneur général d'Indochine » (General Governor of Indochina), strove to strengthen ties between Laos and France. This policy promoted a bipartisan nationalism – on the one side pro- and on the other side anti- French presence – which would fight each other, once the global conflict ended.

Kou Voravong supported a progressive autonomy encouraged by France, and he was opposed to the nationalist movement Lao-Issara (ລາວອິດສລະ[n 14])[6][7] founded by the Viceroy Chao[n 5] Phetsarath Rattanavongsa (ເຈົ້າເພັດຊະຣາດ ຣັດຕະນະວົງສາ), whose objective was to combat the colonial power and to proclaim the independence of Laos at the end of the war.[8]

March 9, 1945, the Japanese army attacked Indochinese French garrisons, and by a coup, took control of the whole Administration. French officials were arrested and the King Sisavang Vong (ສີສະຫວ່າງວົງ), declared under duress, the country's independence. Early in the occupation, some French army officers were air-dropped and organised clandestine resistance operations in the jungle. Kou Voravong immediately contacted the anti-Japanese guerrilla group parachuted into his district (Paksane), a unit commanded by Colonel Jean Deuve.[n 15] On order, he remained at his post for secretly and actively support the French-Lao guerrilla actions: volunteers recruitment, food and weapons supplies, information's collects, munitions hiding. As « chef de l'administration parallèle » (Leader of the Parallel Administration), he conducted anti-Japanese propaganda operations in cities and rural areas, developing resistance and information network. Denounced in June 1945, he was arrested but managed to escape. Accompanied by 150 volunteers, he joined the guerrilla, took up arms and alongside the French-Lao resistance fighters, continued fighting until the end of the war.[7]

Anti-Lao Issara activities

On August 15, 1945, Japan Empire's collapse resulting of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki's nuclear bombing, provided to French Government the opportunity to reestablish its authority over Indochina.

_lors_de_l'inauguration_de_l'Institut_d'%C3%A9tudes_bouddhiques_%C3%A0_Vientiane%2C_en_1931.jpg)

King Sisavang Vong declared officially the French protectorate's continuity. But on September 11, his cousin and Viceroy, Chao Phetsarath accompanied by his two brothers,[n 16] Chao Souvanna Phouma (ເຈົ້າສຸວັນນະພູມາ) and Chao Souphanouvong (ເຈົ້າສຸພັນນຸວົງ), supported by Chinese and Viêt Minh nationalists, proclaimed the Lao Issara Government and required the immediate independence of Laos, refusing all discussions with France.[9] Therefore, struggles between different factions started out.

Appointed Governor (Chao Khoueng) of Vientiane Province since late 1945, Kou Voravong created a civic guard[n 17] and directed the political and military struggle of Monarchists from the occupied capital, facing the Lao Issara, Chinese and Việt Minh who took control of the major cities of the country. But after some months, besieged, injured and threatened, he had to withdraw into the countryside, where he continued to manage for liberation.[7] On April 24, 1945, French army entered Vientiane. The Lao Issara Government went into exile on the right bank of the Mekong River. The movement dissolved in 1949 and was divided into three factions :

- Chao Phetsarath's historical and intransigent branch which continued the fight in Thailand,

- Chao Souvanna Phouma's moderate branch, which agreed to negotiate with France, and whose members returned to Laos,

- Chao Souphanouvong's armed branch, uniting with Việt Minh leaders, which militarized in Hanoi.[8][10]

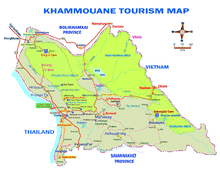

Once Vientiane released, Kou Voravong continued to fulfill his initial function of this province Governor. Then in 1947, he became Governor of Khammouane Province (ຄຳມ່ວນ) whose capital was Thakhek (ທ່າແຂກ).

Paak Hinboun ambush

When relative peace was back in 1946, French Colonial Government whose country hardly recovered from the devastation of World War II, began at the same time to confront some first claims of Vietnamese nationalist movement led by Ho Chi Minh, agreed to lead Laos to progressive autonomy. During this transitional period, Government Commissioners were replaced by delegations of counselors working with Laotian Province Governors.

On the 11th, 1946, an election was organised to set up a constituent assembly. Khammouan Province won 4 seats including Kou Voravong, who had to go to the capital for the development of the Constitution. On March 6, 1947, he undertook the trip, accompanied by 2 other deputies[n 18] and the French counselor of the Savannakhet Province's Governor. On the west side of Khammouane Province, between Thakhek and Paksan, they encountered an ambush, established by a Việt Minh company from Thailand, near a bridge located upstream on the mouth of the Hinboun and the Mekong rivers (Paak Hinboun – ປາກຫິນບູນ). The French counselor and both other deputies were instantly killed; Kou Voravong, seriously wounded, was left for dead. Shot by several bullets, in his head, legs and body, he nevertheless managed to crawl nearly one kilometer in the jungle, to slip into a pirogue and to row along the river until finding assistance. He was then saved, healed at the hospital of Thakhek.[6][11][12]

May 11, 1947, the constitution was promulgated. And by decree dated July, 1947, a new Government was formed, presided over by Chao Souvannarath[n 19] (ເຈົ້າສຸວັນນະຣາດ). The new nation had its Three-headed Elephant flag, its national hymn: Pheng Xat Lao (ເພງຊາດລາວ),[n 20] and a constitution that laid Constitutional monarchy's foundations.

Lao Royal Government Minister

In this first parliamentary royal Government, to the young democrat Kou Voravong was attributed two ministries: Public Works and Justice/Religion.[13] In the same year, with a colleague, Thao Bong Souvannavong (ບົງ ສຸວັນນະວົງ),[n 21] he co-founded the first officially recognized Laotian political party: « Lao Union » (Phak Lao Houam Samphan - ພັກລາວຣ່ວມສຳພັນ):[14] a democratic party with original ideas, which advocated an uncompromising nationalism, but whose members were willing to cooperate with French authorities in order to prepare their country to total independence. But a year later, because of various disagreements with him, Kou Voravong founded his own party: « Democracy » (Phak Paxaathipataï - ພັກປະຊາທິປະໄຕ),[15] fighting as democratically as possible for an independent nation under a Constitutional monarchy.

In his speeches or in his party newspaper, « Voice of Laos » (Xieng Lao – ສຽງລາວ), he stated that links with France were necessary, though he never let pass what he considered as « French invasions » in his country's management.[11] Earlier, in November, 1941, while he was Vientiane Governor's assistant, in the article « Speech to youth », published in the journal « Indochine »,[n 22] he claimed a larger autonomy for Laotian officials, the departure of Vietnamese executives,[n 23] the end of feudal system, the limitation of the Indo-Chinese Federation's competence and more democracy.[5][16]

July 19, France Government admitted for Laos the principle of independence under the Crown of King Sisavang Vong of Luang Prabang within the Indo-Chinese Federation by an agreement between the French President Vincent Auriol and the Laotian Prime Minister, Chao Boun Oum (ເຈົ້າບຸນອຸ້ມ). In order to develop the complete autonomy, Franco-Lao commissions was established to prepare the future transfers of powers. In this second royal Government, Kou Voravong was in charge of the Ministry of Economic Affairs. And in the discussions and debates in these preparation sessions, he was also head of commissions of Plan, Public Works, Economy and Military Affairs.[11]

Laos accessed to complete national sovereignty and had authority to manage its own Justice, Army, Police and Finances. The only restrictions laid down by the General Convention concerned common interests of the four associates countries of the French Union (Cambodia, France, Laos, Vietnam), and the war situation in Indochina.[10] This new status offered to Laos the opportunity to become member of United Nations.

Laos was, therefore, considered as a real State by western countries for the first time in its history. From now on, Lao Government could choose to establish diplomatic relations with any nations in the world and acceded to international organizations. This new situation implies that UN's experts come to evaluate the country's development level and real needs. Among them, there was American economic mission which, at first, was going to intoxicate the Laotian political environment by bringing first greenbacks.[9] Facilitated by the gradual retreat of French neutralist hegemony, this situation left more and more place for pro-American liberal partisans and militarized socialist movements supported by Việt Minh in the Laotian political life.

The delicate balance of unit, stability and international recognition freshly acquired by Laos nation worked out by the confrontation of two opposite political ideologies. From the 1950s and until 1973, because of its geographical location, the Laotian territory became insidiously « the battlefield » of a secret war between CIA and Việt Minh. This resulted in fratricidal political confrontations for power,[n 24] anti-piracy military struggles along the Viet Nam-Laos-Thailand borders, and formation of conspiracies counter-power throughout the territory, especially along the two banks of the Mekong River.

Anti-border piracy fights

.jpg)

From 1951 to 1953, the central government of Laos – a nation under construction – experienced a period of « relative peace », while Indochina War has been raging since 1946, without anyone among the leaders noticing the problems and the political consequences of the progressive and continuous infiltration of the revolutionary guerrillas along the borders. Even if it was politically developing, this 237 000 km2 small landlocked mountainous country, with long and heavily forested borders[n 25] which was difficult to control, populated by numerous ethnic groups,[n 26] where the communication routes were, most of the time, rivers and primitive tracks through the tropical jungle, remained severely sub-administered.[n 27] Its leaders, gathered in major cities, preoccupied by rivalries of privileged clans,[n 28] mined by corruption, demagoguery and personal interests, did not have any control over distant regions, where ethnic minorities problems[n 29] expanded. The villagers considered themselves neglected by the Monarchy and appreciated more and more revolutionary speech of the Pathet Lao's (ປະເທດລາວ[n 30]) Communist cells, founded by Chao Souphanouvong, since his return from exile in 1950, particularly in northern provinces as Houaphan (ຫົວພັນ) and Phongsali (ຜົ້ງສາລີ), which have a common border with North Viet Nam. Ideologically motivated, military trained and organized propagandists, these cells were supported by Ho Chi Minh's party partisans, who operated across both Vietnamese and Thai borders.[17]

As the Prime Minister Chao Boun Oum had submitted the resignation of his government on February, 13th, 1950, the 3rd Royal Government, chaired by Phoui Sananikone (ຜຸຍ ຊນະນິກອນ) was invested on 27th of the same month – just two months before the effective transfers of powers, on April, 13th, Buddhist year 2492's last day[18] – with Kou Voravong as Minister of the Interior.[13] Being himself behind the creation of the National police force in 1949 and consequently very attentive to its development, Kou Voravong imposed on its direction, colonel Jean Deuve, a man of experiment,[n 31] who he could fully trust, for having fought side-by-side four years ago against the Japanese and the Lao Issara troops.[11][19]

The Federal Security Department was, therefore, replaced by the Homeland Security Department, which mission was to prevent and punish violations of internal and external Kingdom's security. In 1949–1950's, the main threats from foreign countries were essentially activities of organizations located in Thailand and in Vietnam, but also from Chinese border, now occupied by Mao Zedong's Revolutionary Army, supporting their Việt Minh brothers-in-arms against the imperialist enemies. It was impossible to control tightly 4 351 km of borders, especially as, all along, lived families from the same lines or the same tribes. Pirates, propagandists or subversive groups easily crossed these porous borders toward distant and off-centered zones, reaching some ethnic minorities neglected by the current government.[20][21]

Instead of solving the minorities problems by informations and dialogue, the Government left the Army with the fight against the guerrilla, which were formed by these same minorities, much more trained, motivated and supervised, while the Indo-Chinese Federation Army, contrary to their opponents, were understaffed[n 32] and could not meet all local needs.[n 33] The activities of these guerrillas Lao-Viet strongly perturbing the internal security, Kou Voravong and Jean Deuve led, since early 1950, a relentless fight against the border piracy. A Psychological Warfare Section and a Police Special Office[22] which employed original but effective methods,[n 34][11][23] was then created in order to support the Indo-Chinese Federation Army.

In 1951, Kou Voravong was elected deputy of his native province and chosen as President of the National Assembly. But military tensions at the borders becoming increasingly strong, the 4th, new royal Government appointed on November 21, 1951 and chaired by the neutralist Chao Souvanna Phouma, called on his veteran's experiences to direct the ministry of National Defense.[11][13]

Signing of the Geneva Agreements

The Indochina War between France and revolutionary Việt Minh troops, led by Ho Chi Minh had been continuing since 1946. It boosted the Pathet Lao's activities, whose president was Chao Souphanouvong starting from 1950.[n 35] He installed the general headquarter of the party in Xamneua, in the North Province of Houaphan.

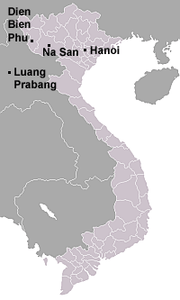

In 1953, when the Pathet Lao, which rebellion expended dangerously, occupied the region of Phongsali, while its allied Việt Minh troops managed to control the Tonkin penetration axes to North, threatening the royal capital Luang Prabang, Laos fully entered into the First Indochina War. On October 23, 1953, a Treaty of Amity and Association was signed and France committed to defend Laos against the advance of communist troops. A garrison assigned under the command of General Henri Navarre – whose mission was to prevent any Việt Minh infiltration to Laos – was implanted in a strategic area, in West Tonkin, close to the Laotian border, where were some important runways connecting Luang Prabang to Diên Biên Phu Basin.

But May 7, 1954, French soldiers suffered a bitter military setback and Diên Biên Phu's entrenched camp fell into the hands of the People's Army of Vietnam, commanded by General Võ Nguyên Giáp. Whereupon, a conference was organized on July 20 in Geneva (Switzerland) to end hostilities between the French Army and the People's Army of Vietnam, ending eight years of war in Indochina. By the same occasion, the independence of Laos and Cambodia was reaffirmed.

At the conference, the Kingdom of Laos delegation was composed of Phoui Sananikone (minister of Foreign Affairs – leader), Kou Voravong (Minister of Defense – vice-leader) and eight members of Parliament. The members of Pathet Lao including Chao Souphanouvong, who carried North-Vietnamese passports, were integrated into the Việt Minh delegation.

The final declaration of the Geneva Agreements provided for Laos:

- Recognition of the independence and total sovereignty of Laos.

- Recognition of Vientiane Royal Government as the legal government of Laos.

- Recognition of the « Fighting Units of the Pathet Lao » grouped in the Xam Neua and Phongsali Provinces, awaiting for their integration into the Royal Army after political settlement through free general elections planned in 1955, under the supervision of the International Commission Control (CIC).

- Withdrawal of the French and Việt Minh military troops of the territory, except for the French instructors placed at the disposal of the Laotian Army.

- Principle of neutrality which prohibited membership in military alliances and introduction of troops and foreign weapons on Laotian territory.

Whereas all details of the cease-fire in Vietnam were settled, the agreement #3 which was equivalent to a recognition of the Pathet Lao as an official authority through its « Fighting Units », divided the royal representatives of the Laotian delegation and extended negotiations till late in the night of July 20. Shortly after midnight, despite the opinion of his delegation's leader, Phoui Sananikone, Kou Voravong finally granted to sign the final declaration, thereby closing the conference on July 21, 1954.

In spite of significant concessions of the Pathet Lao, politically -[recognition of the Government of Vientiane]- as well as military -[withdrawals of the armed forces of the liberated zones and their grouping in Xam Neua (Houaphanh) and Phongsali Provinces] – their official establishment next to the Lao Royal Government pending elections was far from eliciting unanimity. This was particularly true for the U.S. government which refused to sign and to apply the Geneva Agreements, considering that they handed a too large victory to the Indochinese Liberation Movements, headed by the Việt Minh, and supported by China and the Soviet Union. The spectrum of the Korean War just ended is still too present, that's why Washington's policy goal from now on, was to challenge the results of such agreements.

On September 8, 1954, at the initiative of the United States, a military organization SEATO was created. Equivalent of NATO in Southeast Asia, its official goal was to form a "quarantine line" against Communist expansion. It was decided by the authority that Cambodia, and Laos, considering their strategical position, belonged automatically to its protection zone. The defense minister Kou Voravong, supporter of strict application of the Geneva Agreements on the principle of neutrality prohibiting any military alliance, declined the protection of his country by the SEATO and refused to ratify the treaty, thereby blocking the American policy of containment towards the Communist expansion in Asia.

Upon returning of the Geneva delegation, conflicts appeared within the Government. At the same period, rumors of coup by revolutionary conspiracies supporting Chao Phetsarath circulated, creating strong troubles in the country. These extreme tensions reached the summit, when two months later, an attack was committed on September 18, during a reception at Phoui Sananikone's residence, one of the delegates at the Geneva Conference. Present among the dinner guests, hit by a bullet in the back, Kou Voravong died one half an hour later at the Mahosot Hospital (ໂຮງພຍາບານມະໂຫສົດ), in Vientiane.

Assassination and political consequences

September 18th attack

Circumstances and facts

The attack occurred at approximately 22:15, at Phoui Sananikone's, an official residence nearby the Voravong family's. The attackers launched three grenades by one of the windows on the ground floor, in the dining room. They fired three or four pistol shots and then run away. Kou voravong, sitting with his back to the window, was directly hit by a bullet which came in by the kidney and out through the navel, after cutting the vena cava and crossed the liver and intestines. His dead is declared shortly after admission to hospital. A dozen people were injured by the explosion of the grenades, slightly for most of them.

Fifteen minutes later, when the police arrived, it was total confusion: in the panic, people had trampled the crime scene and destroyed evidences. According to witnesses, two men flew away behind the house through the gardens, in the direction of the swamps Muang Noy (ເມືອງນ້ອຍ), located 20 km around Vientiane. Two suspects, Oudom Louksourine (ອຸດົມ ລຸກສຸຣິນ) and Mi (ມີ) were formally recognized, police officers, therefore, set off in pursuit. Even wounded in the arms and legs, Oudom and Mi managed to escape. Supported by local complicity, they succeed in reaching Nong Khai (thai: หนองคาย), on the other side of the Mekong River.

According to the police investigations, one of bullets fired by Oudom Louksourine reached Kou Voravong and caused his death. Oudom was a dangerous and notorious gangster, who confessed to have committed about fifteen assassinations. Imprisoned since 1950, he escaped in 1954 and with Mi -his partner in crime- joined a band of bandits established in Isan region, northeast Thailand, whose leader named Bounkong (ບຸນກອງ), a veteran Lao Issara and faithful follower of Chao Phetsarath.

This band of gangsters was hostile to France and ploted against the Royal Government. It was partly formed by soldiers who have deserted the Chinaimo camp, located near the capital. The conspiracy's members are gathered and hosted by the Thai police under the order of Colonel Praseuth (thai : ประเสริฐ), in Nong Khai, a border city located only 20 km from Vientiane. It appeared clearly that the Thai police, with or without the approval of the Government, supported the plot of Chinaimo which projected to reverse the Souvanna Phouma's government in order to return power to Chao Phetsarath, exiled in Bangkok since 1946. In addition, Thai authority appeared to have an ambiguous policy towards this case: they protected the conspirators of the Bounkong's band at the beginning, before eliminated most of them. They have constantly refused to extradite Oudom Louksourine, who would still sentenced to death in absentia for Kou Voravong's assassination by the Court of Vientiane in July 1959. At that time, he was captain in the Thai police.

Various theories

If there was no doubt about the identity of the one who pulled the trigger, various theories about the person who was behind the crime were advanced by some people, depending on their political, ideological or family affiliations. They were mainly three:

- The plot headed by Bounkong, supported by Thai separatists, sympathizers of both Việt Minh revolutionists and of Chao Phetsarath, was firmly anti-French. Massive desertions from several military camps[n 36] – and among them, the Chinaimo camp – started just after Chao Phetsarath and his Thai wife's visit along the Mekong River, in the Isan region.[n 37][24] Police officers were wondering if the attack were committed on his instructions or simply on his behalf.[25] In addition, investigations revealed that Bong Souvannavong – fervent supporter of Chao Phetsarath's return – had regular contact with members of the conspiracy. His son Boutsabong, would have informed the conspirators of the reception at Sananikone's, which had been although decided in the afternoon. Bong Souvannavong was then arrested and jailed on October 6. According to some conspirators testimony, this attack would be aimed at Phoui Sananikone, who was accused of the anti-Pathet Lao attitude and not having resisted Western pressures on the Geneva Agreements. For some of them, Kou Voravong's death would be first of all an error, which was then exploited to threaten pro-French government members,[26] and for others, it would be a fatal consequence of his intense anti-subversive activity when he was Minister of the Interior,[27] and for still others, that could be an extreme reaction of the French Government to his active anti-feudal militancy for a Laotian led administration.

- Immediately after the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO)'s signing in Manila, Philippines, the Thai Army was deployed in the North and on the East Bank of the Mekong River, along the Laotian borders. Following the refusal of the UNO's Security Council to monitor borders against communist infiltration,[n 38] the Bangkok Government fear facing the Việt Minh was effective, and the Thai Authorities role in this case appeared decisive. Kou Voravong's refusal to join the military organization blocked any US intervention and thus hindered the "containment" policy of which Thailand was part of. During a National Assembly session, Kou Voravong revealed that strong pressures were put on the two Laotian delegation's leaders by the United States so that they refused to sign the agreement's part concerning Laos at the Geneva Conference. Phoui Sananikone would have accepted a one million bribe not to affix his signature. In his speech, Kou Voravong also revealed that the right-wing forces had planned the Pathet Lao's troops suppression, as soon as they were withdrawn from Samneua and Phongsaly Province, as set out in the Geneva Agreements. And lastly, nine days before his murder, he was preparing a meeting between Chao Souvanna Phouma – the Lao Royal Government's chief – and his half-brother Chao Souphanouvong – the Pathet Lao's leader – for the discussions in order to organize the free elections envisaged by these same agreements. For some circles, particularly in the Communist left-wing, Kou Voravong would have become a target of the Lao-Thai right-wing and the CIA: the main "beneficiaries" of his death being the Thai and American governments who considered the Geneva Agreements as a serious concession from France to communist bloc countries.[28][29][30]

- This affair confronted the three most influential rival families in Laos: the Sananikones, the Souvannavongs and the Voravongs. This was typical in Lao political circles where conflicts of families or personalities were mingled with national politics. Kou Voravong – leading supporter of the policy of "neutrality" – stood in opposition to the American "anti-communist" policy which started to find many sympathizers, and among them was Phoui Sananikone. Actually, Kou Voravong was murdered at the residence of Phoui Sananikone, who shortly after became Minister of the Interior and hastily got Bong Souvannavong- a left-wing sympathizer – arrested, whom he accused of being the instigator of Chinaimo's conspiracy, and therefore to be behind the assassination. On January 5, 1955, Thai authorities arrested Oudom Louksourine in Bangkok and declared that the latter confessed to having been paid by Phoui Sananikone to kill Kou Voravong, but however refused to extradite him to Laos. The two rival families newspapers then started a violent campaign against Phoui Sananikone and the March 9, 1955, complaints for assassination was filed against him by the Voravong family at the Vientiane Court. Despite of the given judgement which concluded to dismiss the case for insufficient evidence, the resentments persisted and the charges were maintained. From now on, a gap deepened between the Sananikone and Voravong families – conducted now by the General Phoumi Nosavan (ນາຍພົນ ພູມີ ໝໍ່ສະຫວັນ) – the Lao National Army's new chief of staff.[31][32] These conflicts would later largely influence the political events in 1960–62.

This case of "Attack on State Security"[n 39] involved many influential political figures. Lots of questions remained unanswered and the protagonists were never troubled.[n 40] In March 1955, all defendants were granted conditional release by order of the new prime minister – Katay Don Sasorith (ກະຕ່າຍ ໂດນ ສະໂສລິດ) – who also had authority on Interior and Justice. He did not want under any circumstances to open a trial where his name could be mentioned, as well as accusations against his political friends.[n 41][33]

To close the file definitively, in July 1959, the 9th Royal Government, chaired by Phoui Sananikone, brought the case to trial quickly and behind closed doors, dealing exclusively with the assassination of Kou Voravong, in order not to revive "old issues". Apart from that of Oudom Louksourine – sentenced to death in absentia – no other name was pronounced and the judgement legally exonerated Phoui Sananikone of all charges.[34]

State funeral in Vientiane, on September 20, 1954 – Tribute of the Prime Minister.

State funeral in Vientiane, on September 20, 1954 – Tribute of the Prime Minister. Thao Taan Voravong, Kou Voravong's father, firing the funeral pyre.

Thao Taan Voravong, Kou Voravong's father, firing the funeral pyre. Repatriation of ashes to Savannakhet.

Repatriation of ashes to Savannakhet. The funeral urn was placing in the stupa.

The funeral urn was placing in the stupa. Kou Voravong's sepulcher in Savannakhet.

Kou Voravong's sepulcher in Savannakhet.

Political consequences

Political crisis and resignation of the Government

Shortly after the Kou Voravong's murder, Phoui Sananikone tendered his resignation. But it was not made public because of fear of major political crisis considering the current state of tension in the country after the Geneva Conference. Supported by France, the current government was trying hard to apply the agreements signed in Geneva, in particular maintaining political neutrality and integrating the Pathet Lao. But as might be expected, the crisis broke out as soon as revelation, and his resignation led to the fall of the whole government, already weakened by this case.[35]

Negotiations to form the 5th Royal Government[13] were long and difficult. For more than a month, emotions ran high and exacerbated. The positions were violent, and some did not hesitate to exploit the recent attack and the Kou Voravong's murder to threaten their opponents. A two-thirds majority was necessary for a nomination, but no major political party came to get it. A compromise was reached between the two major parties: half members of former neutralist government – pro-French, favoring the strict application of the agreements signed at Geneva – and half members of the progressive opposition – pro-American, opposed to this same agreements – knowing that neither side was intending to grant concessions to the other. The Prime Minister's choice fell on the progressive Katay Don Sasorith to the detriment of his neutralist opponent Chao Souvanna Phouma, considered « far too leftist » by Americans who, recently, took over French in Lao political circles.

US intervention and the Secret War

American intervention in Laos remained discreet and without any local influence until the Geneva Conference. On September 9, 1951, an agreement had been signed between Washington and the Royal Government for economic and, to a lesser extent, military support. Only a small number of Protestant missionaries and a project manager, accompanied by a few USIS[n 42] and CIA's agents were settled in Vientiane, in 1953. But as the independence movement was led by the Communist Party, and Vietnam was geographically close to China and not far from North Korea, USA got interested in the conflict taking place in Indochina. To justify their intervention, the Americans referred to the "Domino theory" that if Vietnam fell into the hands of the Communists, neighboring countries would follow, earned by the contagion or assaulted by military forces from Hanoi. This shift would change radically forces East/West reports in whole Asia.

In the other camp, the battle of Dien Bien Phu's victory enabled Việt Minh to control the area of North-Laos, but Ho Chi Minh nourished a higher ambition for Indochina. Even though the Geneva Agreements decreed the neutrality of Cambodia and Laos, Hanoi considered that the independence of Vietnam could not be complete as long as its two neighboring countries remained under "imperialist domination".[n 43][36] The Hanoi Government undertook since the end of the 1950s, to support the guerrillas to infiltrate South Viet Nam by constructing a logistical network underground in the border region inside Laos, later known as Ho Chi Minh Trail. Considerable economic, technical and military aid from the USSR and China would be granted.

According to the "Domino theory", Americans considered that the defense of South Vietnam should start by that of Laos because of its strategic position.[n 45][37] Washington would first of all seek to influence the Laotian policy circle by encouraging the establishment of pro-American governments in Vientiane,[n 46] before deciding on direct military intervention.

Despite the Geneva Agreements on the neutrality of Laos, the US Department of Defense established, under cover of economic assistance,[n 47][38] a secret paramilitary mission called the "Programs Evaluation Office" (PEO),[n 48][27] operational from December 1955 and composed of plainclothes officers whose mission was to provide military assistance to the anti-communist right-wing armies. From 1955 to 1963, on a total budget of 481 million of assistance to Laos, the United States would spend $153 million to educate, train and equip the Lao National Army, as well as the Hmong guerrillas secret army, commanded by General Vang Pao against the combatants of the Pathet Lao. Then from May 1964, they proceeded to the massive air raids, especially on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and in the Xieng Khouang Province, while their local allies, helped by CIA agents, involved overland.[39] Until the ceasefire in 1973, the United States took over the Second Indochina War and the Laotians would hardly have any more words to say.[n 49]

In June 1958, the "Committee for the Defense of National Interests"[n 50] was created in Vientiane. Its program was the eviction of communist ministers of the "Lao Neo Hak Sat" party[n 51] (ແນວລາວຮັກຊາດ), and the overthrow of the neutralist Government, in order to maintain Laos in the United States orbit. This civic association of young Laotians, anti-communist and renovator, was led by the army strongman, the general Phoumi Nosavan. Born in the Thai-Lao region border (Moukdahane-Savannakhet), he was the nephew of Sarit Thanarat (thai: สฤษดิ์ ธนะรัชต์) – the current Thai Government Prime minister – and first of all, the general Phoumi Nosavan was Kou Voravong's cousin and brother-in-law.

The statue

Creation in Bangkok

During the confrontations in 1946, Phoumi Nosavan had sided with Chao Phetsarath's Lao Issara Government. And then in the aftermath of the defeat, he took refuge in Thailand. Upon his return from exile in 1949, he joined the newly formed Lao National Army, created in March of the same year.

Early in 1950, when Bounkong and his band engaged in violent anti-government campaigns in the South of the country, Kou Voravong created the "Pacification of Southern Laos Mission" to combat internal subversion and border piracy. This organization whose headquarter was based in Pakse, was responsible to bring together supporters, volunteers and former members of the Lao Issara movement, to form units to combat subversion and banditry. Occupied with his ministerial responsibilities in Vientiane, he entrusted the command to his cousin and brother-in-law, the young lieutenant Phoumi Nosavan.

Considering that the Bounkong Band was known in the province, he got in touch with its members and proposed them negotiations so that they convinced the local insurgents to lay down arms and to adhered to the national cause. But the bandits would take advantage of the naivety of the young lieutenant to carry out during several months, acts of banditry, spying and intense anti-government guerrillas, by using the pass, material and funds provided by the chief himself.[40] Despite the failure of the "Pacification of Southern Laos Mission" which has nearly cost his political career, Kou Voravong renewed his confidence in Phoumi Nosavan who would pursue his military career until becoming the Lao National Army's chief of staff, in 1955.

Following Kou Voravong's death, he led his family members in their search for the truth concerning the assassination. In 1960, during the legislative election campaign of Ou (ອຸ) and Bounthong (ບຸນທົງ) – Kou Voravong's half-brothers – the three cousins promised to the Savannakhet population that in the event of electoral success they would pay tribute to their brother and cousin, "the home-grown child", a murdered rising political figure. Ou and Bounthong Voravong shall be both elected assembly members of the Savannakhet Province that year.

Starting from 1959 and during six years, with the financial support of the CIA, the general Phoumi Nosavan became the dominant figure in the Laotian political life. At the height of his career in May 1960, thanks to his relationship with Sarit Thanarat – the current Thai Prime Minister – and in association with Ou and Bounthong Voravong, he commissioned and financed a life-size statue of Kou Voravong at the Department of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Culture of Thailand. In Savannakhet, a "Kou Voravong Stadium" was built at the extreme north of the avenue of the same name, and the site of the statue was planned on an esplanade just at the entrance.

But the country was immersed in a civil war, itself within the context of the Cold War. In 1963, when his uncle the General Sarit Thanarat died, he lost Thailand's Government support, while on the other side, the United States opted for direct military intervention policy. At the end of January 1965, after several "disobediences" to the American military advisory, and following a coup against his government, whose instigator was General Kouprasith Abhay, Phoumi Nosavan was forced to go into exile in Thailand with his followers and relatives. The statue of Kou Voravong had not been erected and still waiting in the reserve of Fine Arts Department in Bangkok during nearly 30 years.

Back to Savannakhet

_en_1951.jpg)

After a first relationship with Nang Meng (ນາງເມັງ) with whom he had a son – Thao Bouaphet (ທ້າວບົວເພັດ) – Kou Voravong, a young official at the time, married in 1938, Nang Sounthone Souvannavong (ນາງສູນທອນ ສຸວັນນະວົງ), a young nurse / midwife at the Mahosot Hospital in Vientiane. From this union four children were born: Thao Anorath (ທ້າວອະໂນຣາດ) – Nang Phokham (ນາງໂພຄຳ) – Nang Phogheun (ນາງໂພເງິນ) and Thao Anouroth (ທ້າວອນຸຣົດ).

Thao Bouaphet and Nang Phokham went to live in Thailand with their families in 1965, following their uncle, the general Phoumi Nosavan.[n 52] With the exception of Anorath who died in Laos short after his return from the Sam Neua "rehabilitation camp", all of them would emigrated to France from 1976, when the Communist Party Neo Lao Hak Sat (NLHS) came to power and proclaimed the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR).

When the general Phoumi Nosavan died in Bangkok in 1985, since the time-limit for conservation by the Department of Fine Arts was thirty years, questions arose regarding the statue of Kou Voravong. In 1989, the collapse of the communist Eastern Bloc – symbolized by the Berlin Wall's fall – allowed gradually Laos to enter the market economy, which then provided the opportunity for the Voravong children to approach the LPDR authorities for the return to the country of their father's statue.[41] In 1992, the cost of conserving paid, the statue was legally returned to the family. The eldest daughter of Thao Bouaphet, who lived in Bangkok, entrusted it to the monastery of Amphawan (thai language: วัดอัมพวัน), around the Thai capital.

Permission to return to Savannakhet was issued in early 1994 by the Government of Laos. After another year of waiting in the Vat Xayaphoum Temple in Savannakhet, the statue was ceremoniously erected on Saturday, January 7, 1995 by the family and officials, on the private land adjacent to the family residence.[4] On this occasion, a host temple for monks and travelers (ກຸຕິ) was built and offered to the Vat Xayaphoum Temple by the family of Nang Somnuk (married Simukda – ນາງສົມນຶກ ສີມຸກດາ) – one of Kou Voravong's three half-sisters – in association with Thao Anouroth, the youngest son.

Although it is located within a family property and therefore considered by the Government as a private monument, the statue remains visible to the general public and may nevertheless be extended to general knowledge.[42] Situated at the corner of "Soutthanou Street" and "Kou Voravong Street",[n 53] it is presented as a "curiosity" of Savannakhet City by some tourist guides as the site is located coincidentally in front of the birthplace of Kaysone Phomvihane – the very first president of the Lao People's Democratic Republic.[43]

As for the city of Thakhek, the capital of Khammouan Province, a tribute was paid to the former governor Kou Voravong by giving his name to the main street which was completed in 2003.[44][n 54]

1954: aristocratic style portrait served as model for the creation of the statue.

1954: aristocratic style portrait served as model for the creation of the statue. 1995: January 7, the statue was erected in Savannakhet.

1995: January 7, the statue was erected in Savannakhet.- 2015: in front of the family residence.

2018 : close-up of the bust.

2018 : close-up of the bust.

Notes

- Henri Mouhot in 1860, then Francis Garnier under the command of Commander Doudart de Lagrée in 1864.

- The Siamese authorities restored the acquired territories and recognized therefore implicitly the authority of France on the left bank of the Mekong River.

- The number of provinces varied from 10 at the beginning of the century, to 12 by 1947, and up to 17 in the current time.

- The ancestor of Kou Voravong, appointed "Chao Muong" at the beginning of the century by the colonial administration, would be a bandit! Histoire de Savannakhet

- Respectful titles: "Phagna" = lord - "Thao"= Sir - "Nang"= lady - "Thaan-krou"= professor and "chao/tiao"= chef/prince or princess - "Gna Pou"= grandfather.

- Former name of the city of Savannakhet.

- From his mother's remarriage with Thaan-krou Di Voravong (ທ່ານຄຣູດີ ວໍຣະວົງ), Kou Voravong had two half-brothers (also deputies and ministers) and three half-sisters.

- Education system based on "The General Regulation of Public Instruction" (RGIP), introduced on December 21, 1917 by Albert Sarraut, Governor General of Indochina. "Œuvre scolaire française au Vietnam" (PDF) (in French) (198). Bulletin d'information et de liaison de L'association des anciens du Lycée Albert Sarraut de Hanoi. 2014: 33. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Although these high schools were called "collège, students were much older than the "schoolchildren" of France and the academic cycle (which led to a local high school diploma) was shorter (2 years instead of 3, in France).

- It was a charge of misappropriation of public funds, which the Government Commissioner Urbain Malpuech, in office at Savannakhet from 1921 to 1930, would be the accuser.

- His name is given to the old soccer stadium of Savannakhet, now a sports park.

- For the Savannakhet Province, probably Mr Delmas (1929), then Mr Détrie (1930).

- "Got back" by France in 1893, then by the Siam in 1941, these territories are definitively returned to Laos in December, 1946, after the defeat of Japan.

- In Lao : « Free Laos »

- Parachuted with nine other members of the Force 136 in the night of 21–22 January 1945.

- Le vice-roi Bounkhong (death in 1920) had 11 wives and 23 children. Of his first wife: Chao Phetsarath Rattanavongsa and Chao Souvanna Phouma. From his 11th wife, a servant of the Palace: Chao Souphanouvong.

- Militia citizen formed by volunteers, constituting an auxiliary strength of the army.

- Probably Thao Tem Chounlamountry (ທ້າວເຕັມ ຈຸນລະມຸນຕຣີ) et Thao No Gneun (ທ້າວໜໍ່ເງິນ) – former Governor of the province of Thakhek.

- Another half-brother of Chao Phetsarath, who supported the King, and had fought for France.

- Lyrics and translation into English "Laotian National Anthem - Pheng Xat Lao (ເພງຊາດລາວ) - Before 1975".

- Colleague but also brother-in-law, because Kou Voravong married, in 1938, Nang Sounthone (ນາງສູນທອນ), one of the young sisters of Bong Souvannavong.

- French Illustrated weekly magazine, .

- There were only a hundred or so French in Laos at the beginning of the century. That why The Laotian people had the unpleasant surprise to see arriving massively his Vietnamese hereditary enemy to manage the public service.

- The major problem of Chao Souvanna Phouma as Prime minister from now on, was to reduce the dissidence which compromised the unity of the country. From East, by his communist half-brother, Chao Souphanouvong, and from West, by the subversive plots in the region of Issan (thaï : อีสาน) stirred up by the partisans of his older brother, Chao Phetsarath.

- The longest was the Laos-Vietnam border (1693 km), almost as long as the Laos-Thailand one (1635 km), Laos-Cambodia (404 km), 391 km Laos-China, without mentioning Laos-Burma border.

- Approximately 80 ethnic groups, grouped in 4 families according to the altitude of their habitats: Lao Loum (plains), Lao Theung (average altitude), Lao Soung (mountains above 1000 m) and other Asians.

- Only 400 officials and 700 technical services executives to ensure a permanent presence in 12 provinces, 60 districts, 600 cantons and 10 000 villages.

- The most visible rivalry takes place in Vientiane between the Souvannavong, les Sananikone and Voravong families.

- Poverty, banditry, constant propaganda anti-government and military recruitment more or less forced from the revolutionaries.

- In Lao: « Lao Nation ».

- Captain at the time, Jean Deuve had just led for more than three years, the Service of intelligence of Forces of Laos.

- Eight battalions for the whole twelve provinces.

- Protection of official authorities, tax collectors, construction sites and bridges.

- System of intelligence, information and misinformation, adaptation of the police methods to mentalities and traditional culture (beliefs in spirits and occult forces), counter-propaganda in countrysides by employing molams (ໝໍລຳ – traditional singers), monks and even by making a film in Laotian.

- Although Chao Souphanouvong was officially at the presidency, the real leader was Kaysone Phomvihane.

- A total of 135 at the end of this case.

- Around May 1954, Chao Phetsarath visited North East Thailand. Leaflets were then distributed propaganda for "liberating Laos" was done in the Lao community in Thailand.

- Request filed late May and rejected on June 18, 1954.

- Mention appearing on official documents of the Ministry of the Interior and the National Police relating to Kou Voravong assassination

- Chao Phetsarath returned to Laos in 1957, without having political activity. Bounkong remained in Thailand. Sentenced to death in absentia in 1959, Oudom Louksourine was not only never extradited, but pursued his career in the Thai police. As for the defectors, they would be allowed, under certain conditions, to get home from April 1955.

- As a friend of Bong Souvannavong, it would appear that Katay Don Sasorith also had close contact with the Bounkong Band.

- USIS was abolished in 1948 as a central organization, but local services abroad retained this title. Its functions were taken over in 1953 by the United States Information Agency (USIA).

- The general Võ Nguyên Giáp wrote in 1950: « Indochina is one strategic unit and a single battlefield. For this reason, essentially strategic, it is futile to talk about the independence of Viet Nam as long as Cambodia and Laos were under imperialism domination. ». Quoted by Nayan Chanda in « Les Frères ennemis », page 115.

- Along the Ho Chi Minh trail, Savannakhet, Xekong, Attapeu and Salavan provinces.

- In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared: "The security of all Southeast Asia will be jeopardized if Laos loses its independence and neutrality. " Cited by Henry Kissinger in "Diplomacy", page 584.

- First of all, the civil governments of Katay Don Sasorith and Phoui Sananikone, then military of general Phoumi Nosavan.

- Through the "United States Operations Mission" (USOM / USaid) – an American aid agency overseas in all areas – whose official carrier is "Air America".

- Upon the discovery of its existence, this mission would be removed in September 1962 for violation of the Geneva Agreements on maintaining the neutrality of Laos. This mission was officially non-existent, the names of the soldiers who served in this operation have been removed from the list of active army personnel service. CIA activities in Laos#Laos 1955

- From 1964 to 1973, the US Air Force carried out over 500,000 bombing missions, 30% of the dropped bombs were unexploded UXO. There are still 80 million UXOs scattered throughout the country.

- In French: Comité de défense des intérêts nationaux (CDIN)

- "Lao Patriotic Front". For electoral activities, the Pathet Lao used another face: in January 1956 was founded the Neo Lao Hak Sat (NLHS), which acceded to the status of authorized political party in 1957.

- Thao Bouaphet worked as a police officer and Nang Phokham was the wife of Captain Valineta Phraxayavong, a Lao Royal Army fighter pilot.

- Often transcribed in one word: "Kouvoravong Road" or "Kouvolavong Road"

- To view the plans of Thakhek and Savannakhet, see Petit futé - Laos 2014-2015 (in French). pp. 261, 274.

References

- François Gallieni (October 1967). "Le Royaume du Lane Xang" (in French) (203). La Revue française de l'élite européenne. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jean Deuve. Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965. pp. 5, 18 (note n°4).

- Urbain Malpuech (1920). Historique de la province de Savannakhet (in French). pp. 25, 26.

- "ຮູບຫລໍ່ພນະທ່ານ ກຸ ວໍຣະວ໌ງ (Kou Voravong's Statue)" (in Lao). ຂ່າວລາວ [Khao Lao, Registered by Australia Post Publication]. February 1995: 4. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Collectif – Jean Deuve. Hommes et Destins: Asie (in French). p. 216.

- Martin Stuart-Fox. "Historical Dictionary of Laos". p. 169. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Collectif - Jean Deuve. Hommes et Destins: Asie (in French). p. 217.

- "Laos - Le " Pays du million d'éléphants " - Chronologie". clio.fr (in French). Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "11.Indépendance du Laos". lgpg.free.fr (in French). Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Jean Deuve. Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965 (in French). p. 19..

- Collectif – Jean Deuve. Hommes et Destins: Asie (in French). p. 218.

- Hugh Toye. "LAOS: Buffer State or Battleground" (PDF). p. 79. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Vang Geu (2012). "4.3 Administrative System". unforgettable-laos.com. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Martin Stuart-Fox. Historical Dictionary of Laos. p. 191. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Martin Stuart-Fox. Historical Dictionary of Laos. p. 79. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Jean Deuve. Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965 (in French). p. 348.

- Jean Deuve. Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965 (in French). pp. 5, 6, 25.

- Jean Deuve. Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). p. 39.

- Jean Deuve. Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). p. 42.

- Jean Deuve. Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). p. 13.

- Jean Deuve. Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965 (in French). pp. 271, annexe 4 – Maquis lao-viet au Laos 1950–1953.

- Jean Deuve. Le complot de Chinaïmo (in French). p. 36.

- Jean Deuve. Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). pp. 66, 86, 100.

- Jean Deuve. Le complot de Chinaïmo (in French). p. 48.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Arthur J. Dommen. The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans. p. 306.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jean Deuve. Le complot de Chinaïmo (in French). pp. 78, 81, 107.

- "Initial Difficulties". U.S.Library of Congress. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Savèng Phinith. Histoire du Pays Lao (in French). p. 149.

- Wilfred Burchett (23 May 1975). "Laos – Encore un "domino" de tombé". L'unité (in French) (159). pp. 20–21.

- Wilfred Burchett. The Furtive War. pp. A Fateful Assassination. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Savèng Phinith. Cav Bejráj burus hlek hen râjaânâckrlâv (in French). p. 328. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Phetsarath Rattanavongsa. Iron man of Laos. Translated by John B. Murdoch. p. 86.

- Jean Deuve. Le complot de Chinaïmo (in French). p. 104.

- Jean Deuve. Le complot de Chinaïmo (in French). p. 108.

- Hugh Toye. LAOS – Buffer State or Battleground – The Problem of Neutrality (PDF). pp. 106–107. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Chanda Nayan (1987). Presses du CNRS (ed.). Les Frères ennemis – La péninsule indochinoise après Saïgon. Translated by Jean-Michel Aubriet; Michèle Vacherand. Paris. p. 115. ISBN 2-87682-002-1.

- Henry Kissinger (1996). Fayard (ed.). Diplomatie. Translated by Marie-France de Paloméra. Paris. p. 584. ISBN 978-2-213-59720-1.

- Viliam Phraxayavong. "4. History of aid to Laos: 1955–1975". History of Aid to Laos.

- Xavier Roze. Géopolitique de l'Indochine (in French). p. 47.

- Jean Deuve. Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). pp. 77–80.

- Collective work – Grant Evans (scholar). Cultural Crisis and Social Memory. pp. 161–162.

- Collective work – Grant Evans (scholar). Cultural Crisis and Social Memory. p. 167.

- Jan Düker (2013). Savannakhet-Museen und Monumente (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- "ເສັ້ນທາງ ກຸ ວໍລະວົງ ແລະ ເຈົ້າອນຸ ຈະກໍ່ສ້າງໃຫ້ສຳເລັດປີ ໒໐໐໓ [The project completion of the avenues "Kou Voravong" and "Chao Ano" planned for 2003]". ປະຊາຊົນ [Newspaper Passasson] (in Lao). No. 9050. 31 December 2002.

Bibliography

- Collectifve work, Dir. Robert Cornevin (1985). Académie des sciences d'outre-mer (ed.). Hommes et Destins : dictionnaire biographique d'outre-mer – Asie (in French). VI. Paris. pp. 216–218.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jean Deuve (2003). L'Harmattan (ed.). Le royaume du Laos 1949-1965 - Histoire événementielle l'indépendance à la guerre américaine (in French). Paris. pp. 1–63. ISBN 2-7475-4391-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jean Deuve (1986). Travaux du Centre d'histoire et civilisations de la péninsule indochinoise – Histoire des peuples et des États de la Péninsule Indochinoise (ed.). Le complot de Chinaïmo - Un épisode oublié de l'histoire du Laos (1954-1955) (in French). Paris. pp. 76–108. ISBN 290495502X.

- Jean Deuve (1998). L'Harmattan (ed.). Histoire de la police nationale du Laos (in French). Paris. pp. 145–147. ISBN 2-7384-7016-5.

- Savèng Phinith (1971). Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient – Comptes rendus (ed.). Cav Bejráj burus hlek hen râjaânâckrlâv toy 3349 (in French). pp. 314–328. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Savèng Phinith; Phou-Ngeun Souk-Aloun; Vannida Thongchan (1998). L'Harmattan (ed.). Histoire du Pays Lao – De la Préhistoire à la République (in French). p. 149. ISBN 2738468756..

- Phetsarath Rattanavongsa (1978). "The Murder of Kou Voravong, Defense Minister of Laos". In David K.Wyatt (ed.). Iron man of Laos: prince Phetsarath Ratanavonga. Data paper / Cornell University, Southeast Asia program. 110. Translated by John B. Murdoch. Ithaca, New York: Cornell university. p. 86. ISBN 0-87727-110-0.

- Martin Stuart-Fox (2008). Scarecrow Press, 3rd edition (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Laos. pp. 79, 169, 191, 322. ISBN 0810864118. Retrieved 20 September 2015..

- Wilfred Burchett (1970). "Laos and its Problems". In International Publishers (ed.). The Second Indochina War – Cambodia and Laos. New York. pp. 87–96. ISBN 0717803074..

- Wilfred Burchett (1963). International Publishers (ed.). The Furtive War – The United States in Laos and Vietnam – Fateful Assassination. New York. ISBN 9781463721596. Retrieved 20 September 2015..

- Arthur J. Dommen (2002). Indiana University Press (ed.). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans – Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-0-253-33854-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link).

- Grant Evans (scholar) (2002). Allen & Unwin (ed.). A Short History of Laos – The Land in Between. Australia. ISBN 9781741150537..

- ກຣານສ໌ ເອແວນສ໌ (2006). Silkworm Books (ed.). ປະຫວັດສາດໂດຍຫຍໍ້ຂວງປະເທດລາວ – ເມືອງຢູ່ໃນກາງແຜ່ນດິນໃຫຍ່ອາຊີອາຄະເນ (in Lao). Bangkok. ISBN 9789749511213..

- Hugh Toye (1968). Oxford University Press (ed.). LAOS – Buffer State or Battleground (PDF). London. p. 79. Retrieved 20 September 2015..

- Andreas Schneider (2001). Institut für Asien und Afrikawissenschaften – Hurnboldt Universität – Südostasien Working Papers (ed.). Laos im 20. Jahrhundert: Kolonie und Königreich, Befreite Zone und Volksrepublik (PDF) (in German). 21. Berlin. pp. 43, 48, 63. ISSN 1432-2811. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015..

- Viliam Phraxayavong (2009). Mekong Press (ed.). History of Aid to Laos – Motivations and Impacts. OCLC 320802507..

- Christian Taillard (1989). Reclus-La documentation française (ed.). Laos, stratégies d'un État-tampon (in French). Montpellier.

- Charles F. Keyes; Shigeharu Tanabe (2013). Routledge (ed.). Cultural Crisis and Social Memory – Modernity and Identity in Thailand and Laos. pp. 161, 162, 167. ISBN 9781136827327..

- Xavier Roze (2000). Economica (ed.). Géopolitique de l'Indochine – La péninsule éclatée (in French). Paris. ISBN 2-7178-4133-4..

- Collective work (2014). Petit futé – Country Guide (ed.). Laos 2014-2015 (in French). Paris. ISBN 9782746972896..

- Jan Düker (2016). Mair Dumont DE (ed.). Laos: Zentrallaos: Ein Kapitel aus dem Stefan Loose Reiseführer Laos (in German). ISBN 9783616407456..