Kosen judo

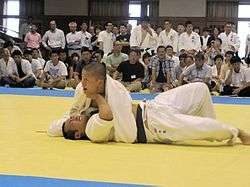

Kosen judo (高專柔道, Kōsen jūdō) is a variation of the Kodokan judo competitive ruleset that was developed and flourished at the kōtō senmon gakkō (高等専門学校) (kōsen (高專)) technical colleges in Japan in the first half of the twentieth century. Kosen judo's rules allow for greater emphasis of ne-waza (寝技, ground techniques) than typically takes place in competitive judo and it is sometimes regarded as a distinct style of judo.[1]

Currently the term "kosen judo" is frequently used to refer to the competition ruleset associated with it that allows for extended ne-waza. Such competition rules are still used in the Nanatei Jūdō / Shichitei Jūdō (七帝柔道, Seven Imperials Judo) competitions held annually between the seven former Imperial universities. Similarly, there has been a resurgence in interest in Kosen judo in recent years due to its similarities with Brazilian jiu jitsu.[2]

History

Kosen (高専, kōsen) is an abbreviation of kōtō senmon gakkō (高等専門学校), literally 'higher speciality school', and refers to the colleges of technology in Japan that cater for students from age 15 to 20. The kosen schools started holding judo competitions in 1898,[3] four years after their opening, and they hosted an annual event of inter-collegiate competitions called Kosen Taikai (高專大会, Kōsen Taikai) from 1914 to 1944.[4]

The rules of a kosen judo match were mainly the ones codified by the Dai Nippon Butokukai and Kodokan school prior to 1925 changes. However, they differed in that they asserted the right of competitors to enter groundwork however they wished and to remain in it as long as they wanted, as well as perform certain techniques which were forbidden in regular competition.[5][6] Naturally, this kind of rules allowed to discard tachi-waza and adopt a more tactical style of ne-waza, which was developed profusely under the influence of judoka like Tsunetane Oda and Yaichihyōe Kanemitsu.[7]

It is believed that the popularity of those strategies was the reason why Kodokan changed its competitive ruleset, restricting ground fighting and entries in 1925 and replacing draws for decision victories or yusei-gachi in 1929.[4] Jigoro Kano was reportedly unsatisfied with kosen rules, and was quoted in 1926 as believing that kosen judo contributed to create judokas more proficient at winning sport matches at the cost of being less skilled at self-defense.[8] Despite his posture, the kosen movement continued on, having barely changed its rules through all its story.

In 1950, the kōtō senmon gakkō school system was abolished as a consequence of education reforms, but the kosen ruleset was adopted by the universities of Tokyo, Kyoto, Tohoku, Kyushu, Hokkaido, Osaka and Nagoya, collectively known as Seven Imperial Universities. They hosted the first inter-collegiate competition, Nanatei Jūdō (七帝柔道), in 1952, giving birth to another annual tradition.[9] The Tokyo University abandoned the Nanatei league in 1991 in order to focus on regular judo, but it was reincorporated in 2001.[10]

The Kyoto region is particularly notable on the kosen judo scene, having schools entirely specialized on this style until around 1940.[1][11] Among the seven universities, Kyoto has the highest number of victories at the Nanatei league, counting 22 wins and 3 draws (against Nagoya in 1982 and Tohoku in 1982 and 1983) out of the 66 editions celebrated as of 2017.

Ruleset

Unlike mainstream Kodokan competition rules, kosen rules allow hikikomi (引込, pulling-in), enabling competitors to transition to ne-waza by dragging their opponent down without using a recognised nage-waza technique (analogous to pulling-guard).[12] It is also allowed to remain on the ground as much time as it is necessary, regardless of the contenders' activity.[6] The judoka can grab his opponent as he wants, including at the legs and trousers, and there is no restriction on defensive posture.[12] Techniques like neck cranks and leglocks were legal (excluding ashi garami, which was still a forbidden technique or kinshi-waza), though only until 1925.[6] Finally, winning can only be accomplished by ippon, being the only alternative a hikiwake or technical draw at the referee's discretion.[6]

The matches are contested on a mat 20×20 meters in total size. A starting zone 8x8 meters was marked on the mat as well as a danger zone which ended at 16×16 meters. If a judoka went out of the danger zone the match would be restarted. If they were actively engaged in newaza the referee would call sono-mama to freeze them into position, drag them to the middle of the competition area, and call yoshi to restart the match in the same situation. This device was common in judo in general and is still part of the official judo rules, addressed in article 18, but has since fallen into disuse, allowing modern judoka to escape newaza by going out of the competition zone.

At the Nanatei Judo league, universities face off in teams of 20 judoka of any weight class: 13 of ordinary contenders, a captain and a vice-captain, and five replacements in case of injuries or retirements. Every match is composed of a single, six-minute round, changed to an eight minute round when the contenders are captains or vice-captains. The league is hosted as a kachi-nuki shiai, meaning every winner stays on the mat to face the next member of the rival team. At the end of the event, victory is given to the team with the highest numbers of matches won or with the last man on the field.[13]

Famous kosen judoka

- Hajime Isogai, teacher and referee at several schools.

- Tsunetane Oda, competitor at the Numazu koto senmon gakko and teacher at several schools.

- Yaichihyōe Kanemitsu, teacher at several schools.

- Masahiko Kimura, competitor at the Takudai tournament in Takushoku University.

- Tatsukuma Ushijima, competitor and teacher at several schools.

- Kanae Hirata, teacher at several schools and founder of the Newaza Kenkyukai dojo.

- Yuki Nakai, retired mixed martial artist, founder and main teacher of Paraestra Shooto Gym and current chairman of the Japanese Brazilian jiu-jitsu Federation. Former Nanatei competitor for the Hokkaido University.

- Shiko Yamashita, retired mixed martial artist. Former Nanatei competitor for the Hokkaido University.

- Koji Komuro, competitor of Brazilian jiu-jitsu, sambo and submission grappling. Teacher at the Tokyo University.

- Mikio Oga, Brazilian jiu-jitsu competitor. Former Nanatei competitor for the Kyushu University.

- Akihisa Iriki, Brazilian jiu-jitsu competitor. Former Nanatei competitor for the Osaka University.

- Matsutaro Shoriki, journalist and media mogul. First and only non-professional 10th dan judoka in history. Competitor at the Takaoka koto senmon gakko and later Nanatei competitor for the Tokyo University.

- Yasushi Inoue, novelist, poet and essayist. Competitor at the Hamamatsu koto senmon gakko and later Nanatei competitor for the Kyushu and Kyoto universities.

- Toshiya Masuda, novelist and essayist. Former Nanatei competitor for the Hokkaido University.

- Taku Mayumura, novelist. Former Nanatei competitor for the Osaka University.

- Masatoshi Wakabayashi, politician. Former Nanatei competitor for the Tokyo University.

- Naohiro Dōgakinai, politician. Former Nanatei competitor for the Hokkaido University.

- Toranosuke Katayama, politician. Former Nanatei competitor for the Tokyo University.

- Nobuaki Sato, politician. Former Nanatei competitor for the Tokyo University.

- Yoshiaki Harada, politician. Former Nanatei competitor for the Tokyo University.

- Kosuke Morita, nuclear physicist. Former Nanatei competitor for the Kyushu University.

Bibliography

- Green, Thomas A.; Svinth, Joseph R. (2003), Martial Arts in the Modern World, Westport, CT: Praeger

- Kashiwazaki, Katsuhiko (1997), Osaekomi, Ippon Books

- Judo History Archive

References

- Green and Svinth 2003, p282

- Cunningham, Steve (Fall 2002), "What is Kosen Judo?", American Judo, p. 23

- Yaichibei Kanemitsu, Shin Shiki Judo, 1925

- Hoare, Syd (August 2005), Development of Judo Competition Rules (PDF), retrieved August 26, 2014

- Hoare, Syd (2009), A History of Judo, London: Yamagi books, p. 151

- Kashiwazaki, Katsuhiko (1997). Osaekomi. London, UK: Ippon Books. p. 14. ISBN 1-874572-36-4.

- Okada, Toshikazu, "Master Tsunetane Oda", Judoinfo.com, retrieved August 24, 2014

- Risei Kano, Jigoro Kano and the Kodokan - An Innovative Response To Modernisation

- Jujutsu & Newaza, Sensei St. Hilaire

- Ryuichiro Matsubara, Nanatei Judo, Gong Kakutogi, 2001

- Jujutsu & Newaza Archived 2005-09-06 at the Wayback Machine, Sensei St. Hilaire

- Shichitei Judo shiai rules (unofficial translation)

- Matsumoto, Masafumi, Why Do Kosen Judo Players Insist on Guard Pulling?, BJJ Eastern Europe, retrieved March 19, 2017