Kokichi Nishimura

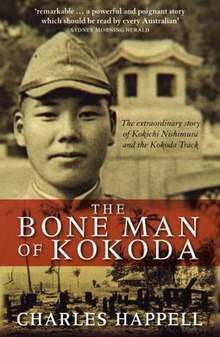

Kōkichi Nishimura (西村幸吉, Nishimura Kōkichi, December 8, 1919 – 25 October 2015) was a Japanese soldier and businessman who devoted his post-retirement years to traveling to Papua New Guinea to recover the remains of his former comrades and other Japanese soldiers who died during the Second World War. His life was described in the 2008 book The Bone Man of Kokoda by Australian journalist Charles Happell.[1]

Kōkichi Nishimura | |

|---|---|

| Born | 8 December 1919 Kōchi Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | 25 October 2015 (aged 95) Saitama Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Gochō (Corporal) |

| Unit | IJA 55th Division |

| Battles/wars | World War II (New Guinea campaign, Burma Campaign) |

Childhood and prewar

Nishimura grew up in Kōchi Prefecture in Shikoku. He had three siblings, and their father became ill and died when he was nine, and Nishimura worked to help support his family. When he was 11 the family moved to Ota Ward in Tokyo and he worked in a factory by day while studying at a technical school by night. At 15 he became a fitter and machinist in a factory, and began to build a reputation as a trouble-shooter. He returned to Kochi City for his military medical examination in 1940 and was conscripted the following year.[2]

Wartime experience

Nishimura was assigned to the 3rd platoon of the 5th company of the 144th Regiment of the South Seas Detachment (南海支隊, nankai shitai) under Major General Tomitarō Horii. After six months of difficult training which included severe beatings from officers, he and his unit shipped out of Kochi on September 22, 1941 on the Yokohama Maru. After meeting no resistance from the Americans on Guam, and relatively light resistance from the Australians on New Britain,[3] Nishimura's unit was deployed to New Guinea.

The Yokohama Maru was sunk by air attack, and Nishimura's unit took part in the thrust towards Port Moresby and fought on the Kokoda Track. After surviving being shot three times Nishimura was the only man of his 56-member platoon to survive the Battle of Brigade Hill, referred to by the Japanese as the Battle of Efogi.[4]

After an extremely difficult retreat to the north coast of New Guinea, Nishimura was part of the besieged Japanese forces in Girua. The starving garrisons resorted to cannibalism of dead Allied soldiers and Papuans, and sometimes their own dead, which they referred to as "white pork" and "black pork". Nishimura did also.[5][6]

In late 1942 he was made a platoon leader, and promoted to Lance-corporal.[7] Evacuated from New Guinea to the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul in New Britain, he weighed 28 kilograms. After recuperating, he left on the Kozan Maru, which was sunk by an American submarine just off Taiwan. He was injured and once again hospitalized. In October 1943 he was sent to Burma, where the 5th company fought against the British army. He was again wounded and later struck down with malaria, and in 1944 he was sent to Singapore on the way back to Japan. His ship was damaged and put in at Taiwan for repairs, finally arriving back in Asakura in Kochi on January 8, 1945. Suffering from malaria once again, he was in a Kochi hospital when the war ended.[8]

Postwar life

In late 1945 Nishimura married Yukiko, five years his junior. He was introduced to her on an omiai (arranged matchmaking date) organized by a classmate of his mother, on the condition that he would return to New Guinea to retrieve the bodies of his comrades. They had four children, three sons and a daughter.

The Military Police (MPs) were very active at this time and while he had not been involved in any war crimes, he didn't trust the MPs, and avoided ports and railway stations due to their checkpoints. He worked various jobs around Shikoku and set up the Kochi Prefecture Cooperative to arrange jobs for unemployed veterans, widows and families who had lost men in the war. The postwar Occupation of Japan formally ended in 1952, and in 1955 he returned to Tokyo.

He founded the Nishimura Machinery Research Institute in Tokyo's Ota Ward. The firm is still in business as of 2018.[9] He once again developed a reputation as a trouble-shooter and became friends with Akio Morita, the founder of Sony, who dealt with him directly. He also did work for Hitachi and developed a relationship with its president. He developed a rotary engine for motor vehicles but refused to sell it to Isuzu Motors when it became clear that it would sell the information to a foreign company.

His oldest and favorite son Akira died in a car accident in 1966 at age twenty. Over the years Nishimura visited the mostly empty graves of his dead comrades, and also visited their relatives. He gradually made plans to return to New Guinea to retrieve his friends' bodies. He was partly inspired in the 1970s by the return to Japan of the holdouts Shōichi Yokoi and Hiroo Onoda who had refused to accept word of Japan's surrender, and the fact that the war was being forgotten by the Japanese public also spurred him on.[10]

He was a member of the Kochi-New Guinea Association, a veterans group, which disapproved of his plans to recover bodies without going through official government channels. Sadashige Imanishi, a senior member of the association and a friend of Nishimura, had been on a 1969 recovery operation with the Ministry of Health and stayed in Popondetta. Dozens of bodies were recovered and cremated, and then placed in Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Tokyo.[11]

In 1979 when he told his wife Yukiko and their children of his plans to return to New Guinea post-retirement, she argued against it, as did his two surviving sons. His daughter Sachiko supported him, and the family split down the middle. He gave his wife almost all of his property and never saw her nor their remaining two sons again.[12][13] When interviewed later in life, Nishimura stated that he could not even remember his wife's name, and that his sons are "nothing to do with me."[14]

The Bone Man of Kokoda

In 1979 Nishimura made a short trip to Papua New Guinea, which had only just become independent from Australia in 1975. He went again in 1980. He built a house in Popondetta to use as a base. He did some work helping to train locals as mechanics, got a ten million yen Japanese government grant to build a school, and got approval from PNG parliament members Michael Somare and Stephen Tago to look for Japanese remains.[15]

A Japanese documentary about his work was aired in Japan, which resulted in some publicity and Yoshiki Miyagi of Shinko Trading providing and shipping earthmoving equipment to PNG free of charge, to be used to build roads. Nishimura started searching for bodies in earnest and found 120 at Girua beach, and 60 around the Buna and Gona areas.[16]

Life in PNG was challenging, with his Popondetta house being burglarized a number of times, and he also had some issues with Hirozaku Yasuhara, a Japanese right wing group member who claimed to be from an organization called the "Remains Recovery Association" (Ikotsu-shu-shudan). Yasuhara attempted to get control of the remains Nishimura had recovered, even having some of them stolen from Nishimura's house. Yasuhara also sent a demand through the Japanese embassy to the government back in Tokyo demanding ¥64 million or they wouldn't receive any remains. The money was not paid, leaving locals angry with Yasuhara.[17]

Nishimura continued his recovery work and retrieved 30 to 35 bodies from around Waju.[18] He was very disappointed to learn that the bodies at the Battle of Brigade Hill, site where his platoon was wiped out had later been burned, so he was unable to recover bodies, just a portion of the ash, which he returned to the Gokoku shinto shrine in Kōchi. As of 2017, some items recovered by Nishimura are also housed at the shrine in Kochi.[19] Having been unable to retrieve his comrades, he organized a memorial monument to be built, which was completed on July 5, 1989. Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone had offered to provide some of his private funds to support Nishimura's work, but he refused, worrying that if it became public knowledge it could cause a political scandal for Nakasone.[20]

In 1989 he recovered some remains on South Girua, including a skull with four gold teeth. A bureaucrat from the Japanese Ministry of Health was there at the time, and he demanded that Nishimura turn over all the bones. Nishimura told the bureaucrat that he would not, and that he would have to kill Nishimura to get them. The bureaucrat backed down, and Nishimura gave him a few other bones to allow the bureaucrat to save face, but Nishimura kept the skull.[21]

He continued his work through the 1990s, and helped a number of relatives of the war dead find or look for the places in PNG where they died. As the 50th anniversary of the end of the war approached the Japanese government wanted to collect the bones, and Nishimura was under the impression that they would have them tested and try to return them to their relatives. But the ministry of health did not do so. Just like the remains recovered in 1969 on the trip Imanishi took part in, the remains of the approximately 200 bodies Nishimura had handed over were burned and placed in Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery, not tested or returned to relatives. This infuriated him.[22]

In 1999 Nishimura was in Japan attempting to track down the family of the skull with four gold teeth. After fifty nights of travel and visiting sixty-seven families he finally located the correct family in Shōbara, Hiroshima. The deceased soldier was Takashi Yokokawa, but his family rejected the skull as the dead man had had a bad reputation in the family. Nishimura was incensed but the skull was accepted by Masaaki Izawa of the Japan War-Bereaved Families Association, who helped arrange and pay for a grave in Shōbara cemetery.[23]

A newspaper article about the search for the relatives of the skull caught the attention of Miyo Inoue, a Communist Party member of the House of Councillors, who outlined Nishimura's work in PNG both to recover remains, build memorials to the fallen, and help the local people. She asked the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Chikara Sakaguchi why the Japanese government was not performing these tasks. Sakaguchi said "I can just bow my head for his efforts for his dead friends at the old age of seventy-nine."[24]

From 2000 to 2002 Nishimura worked for Bernard Narokobi, a PNG parliamentarian. This provided him with income and gave him the opportunity to travel many places with Narakobi, opening doors and helping him learn about the locations of more remains. PNG had passed a law that human remains in PNG were the property of PNG, and some remains were being used as tourist attractions by unscrupulous tourist operators. He arranged for Narokobi to travel to Japan to have Japanese officials request that the law be revoked. None of the Japanese officials raised the issue, providing another disappointment.[25]

Return to Japan

In 2005, no longer able to continue his work due to ill health, Nishimura left PNG to return to Japan. He moved in with his daughter Sachiko, an elementary school teacher in Kazo, Saitama.[26] He still suffered from malaria attacks, and estimated that he had spent around 400 million yen on his work recovering remains and tracking down relatives, which included building roads and bridges, as well as buying boats. While no longer able to do as much as he once could, he helped relatives of war dead with information about their relatives when he could.[27]

Final trip to PNG

Wayne Wetherall, a PNG campaign historian and the founder of the Kokoda Spirit trekking company, travelled to Japan in 2009 to meet Nishimura and ask him about Australian Army Captain Sam Templeton, who was missing in action, believed killed by the Japanese. Templeton's son Reg wanted to know what happened to his father, as there had been various conflicting stories, none confirmed. Nishimura believed that he had buried Templeton. Nishimura said he had not been present at Templeton's death, but that he had been captured and when interrogated before Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto, commander of the 144th regiment, lied and said "There are 80,000 Australian soldiers waiting for you in Moresby" and laughed at Tsukamoto, who became enraged and killed him with his sword. Nishimura later found the body with a sword or bayonet blade protruding from its side, and buried it because of the smell. Nishimura returned to PNG in 2010 at 90 years of age, and showed Wetherall the place he believed Templeton was buried, but no body was found.[28]

Last research

In July 2015 at the age of 95 he met Leon Cooper, a US veteran also aged 95 who also has an interest in recovering the war dead of his comrades who died in New Guinea. Just as Nishimura was critical of the Japanese government's efforts, Cooper believed that the US government's efforts to recover remains were still ineffectual.[29][30]

Death

He died in 25 October 2015 at the age of 95.[31]

References

- Pulvers, Roger 'Bone' Man bears lifelong witness to the ugly brute of war April 20, 2008 Japan Times Retrieved on September 17, 2015

- Happell 2008, pp. 11–18.

- Happell 2008, pp. 19–31

- Happell 2008, p. 59.

- Happell 2008, pp. 77–81.

- Norrie, Justin (April 3, 2008). "The digger of Kokoda". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Happell, 2008 p151

- Happell 2008, pp. 83–91.

- "Nishimura Seisakuso". Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Happell, 2008 pp93-120

- Happell, 2008 141-152

- Happell, 2008 115-120

- McNeill, David Finding Papua war dead a vet’s life June 2, 2008 Japan Times Retrieved September 17, 2015

- McNeill, David (July 2, 2008). "Magnificent Obsession: Japan's Bone Man and the World War II Dead in the Pacific". Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Happell, 2008 pp123-133

- Happell, 2008 pp135-140

- Happell, 2008 pp141-152

- Happell, 2008 p147

- Mealey, Rachel (November 2, 2017). "Kokoda families push for Japan to remember war dead". abc.net.au. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Happell, 2008 pp153-162

- Happell, 2008 p194

- Happell, 2008 pp173-180

- Happell, 2008 pp3-10,191-200

- Happell, 2008 pp198-200

- Happell, 2008 pp201-210

- Happell, 2008 pp211-219, 239-245.

- Happel, 2008 pp247-255.

- Coulthard, Ross Kokoda mystery solved April 24, 2010 The Australian Retrieved on September 17, 2015

- Perry, Tony U.S., Japanese veterans, 95, work to find missing comrades July 20, 2015 Los Angeles Times Retrieved August 31, 2015

- Robson, Seth WWII veteran's effort to recover MIA remains in the Pacific bears fruit August 4, 2015 Stars and Stripes Retrieved August 31, 2015

- "友に誓い、戦死者遺骨集め続け26年 95歳元兵士死去" (in Japanese). asahi. 15 November 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

Bibliography

- Happell, Charles (2008). The Bone Man of Kokoda: The extraordinary story of Kokichi Nishimura and the Kokoda Track. Crows Nest: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4050-3836-2.