King Edward VII's Hospital

King Edward VII's Hospital (formal name: King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes) is a charity-registered private hospital in Marylebone, west London.

| King Edward VII's Hospital | |

|---|---|

King Edward VII's Hospital | |

| |

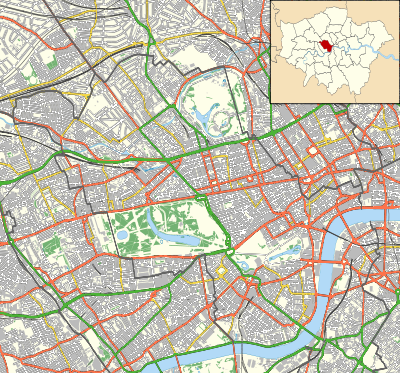

Location in Westminster | |

| Geography | |

| Location | London, W1 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′15.3″N 0°9′1.5″W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Private |

| Funding | Non-profit hospital |

| Type | General |

| Patron | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | No |

| History | |

| Opened | 1899 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

History

Early history

The hospital was established in 1899 at the suggestion of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). Agnes Keyser, a mistress of the Prince,[1] and her sister Fanny used their house at 17 Grosvenor Crescent to help sick and wounded British Army officers who had returned from the Second Boer War.[2] King Edward VII became the hospital's first patron.[3] In 1904 it officially became King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers.[2]

20th century

During the First World War, the hospital was at 9 Grosvenor Gardens, where officers would be nursed; the young novelist Stuart Cloete was one of them,[4] as was the future British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, who underwent a series of long operations followed by recuperation there from 1916–18, from serious wounds sustained in conflict during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.[5] In 1930, the hospital was awarded a Royal Charter[6] "to operate an acute Hospital where serving and retired officers of the Services and their spouses can be treated at preferential rates."[7]

In 1941 the interior of the building was badly damaged by bombing, and Sister Agnes died from natural causes.[2] In 1948 the hospital moved to Beaumont Street.[3] It was officially opened on 15 October by Queen Mary.[2]

In 1962, the hospital became a registered charity.[8]

21st century

In 2000 the hospital and charity changed its formal name to King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes. Originally a hospital for officers, today it is a private hospital which supports the treatment of all ranks of former servicemen, as well as the general public.[3] Through the hospital's Sister Agnes Benevolent Fund, active or retired personnel in the British armed services, as well as their spouses, can receive a means tested grant that can cover up to 100% of their hospital fees.[7]

In recent years, the hospital has been used by various members of the British Royal Family. Previous royal patients at the hospital include Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, and Charles, Prince of Wales.[9]

In February 2002, Princess Margaret died at the age of 71 at the hospital, after suffering a stroke.[10]

In December 2013 it was announced that the hospital had received a donation of £30 million from Michael Uren.[11]

In October 2014 Zambian President Michael Sata died at the age of 77 at the hospital, after receiving treatment for an undisclosed illness.[12]

It generates revenue per bed of £347,000 a year.[13]

Royal hoax call and death of Jacintha Saldanha

In December 2012, the hospital received international media attention when Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge was admitted, suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum. While the Duchess was staying at the hospital, two DJs from the Australian radio station 2Day FM made a hoax telephone call to the hospital, pretending to be Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles.[14] They managed to obtain confidential information about the Duchess and her treatment from a nurse at the hospital. The call was recorded and broadcast after receiving approval from the station management. The hospital apologised, and said that privacy and security protocols would be reviewed.[15] Two days after the broadcast, nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who had worked just over four years at the hospital and had passed on the hoax call to the other nurse in the Duchess's private ward, was found dead. The Metropolitan Police described it as an "unexplained death".[16][17][18] On 14 December, The Guardian reported that it understood that the third of the notes left by Saldanha 'addressed her employers, the hospital, and contained criticism of staff there.' [19]

See also

References

- Meikle, James (7 December 2012). "King Edward VII hospital – the royal choice". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Hospital For Service Officers - New Premises Opened by Queen Mary". Reviews. The Times (51204). London. 16 October 1948. pp. 6.

- King Edward VII's Hospital - About us Re-linked 2016-01-29

- Cloete, Stuart (1972) A Victorian Son, an autobiography, 1897-1922.

- Supermac. Author: D.R. Thorpe. Publisher: Chatto & Windus. Published: 9 September 2010. Retrieved: 1 February 2014.

- The Charity Commission: King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes - Governing document Re-linked 2016-01-29

- King Edward VII's Hospital - Annual Report 2014-2015, page 8 Linked 2016-01-29

- The Charity Commission: King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes - Registration history Linked 2016-01-29

- "Kate admitted to hospital with royal connections". ITV. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "Scots sorrow at death of princess". BBC. 9 February 2002. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "A gift fit for a Queen". Health Service Journal. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Zambian President Sata death: White interim leader appointed". BBC. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Rich overseas patients help private hospitals beat recession". Financial Times. 12 April 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "Jacintha Saldanha, who died in suspected suicide after Kate Middleton radio hoax, was an 'excellent nurse'". National Post. Toronto. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Royal pregnancy: Hoax call fools Duchess of Cambridge hospital". BBC News. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Duchess of Cambridge prank call nurse found dead in suspected suicide". Evening Standard. London. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Hall, John (7 December 2012). "Nurse who took prank phone call at Duchess of Cambridge's hospital is found dead in suspected suicide". The Independent. London. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Vinograd, Cassandra; Kirka, Danica (8 December 2012). "Duchess of Cambridge prank call nurse dies". MSN News. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Jacintha Saldanha suicide notes". The Guardian. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2014.