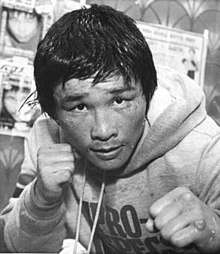

Kim Duk-koo

Kim Duk-koo[lower-alpha 1] (born Lee Deokgu[lower-alpha 2]; July 29, 1955 – November 18, 1982) was a South Korean boxer who died after fighting in a world championship boxing match against Ray Mancini. His death sparked reforms aimed at better protecting the health of fighters, including reducing the number of rounds in championship bouts from 15 to 12.

| Kim Duk-koo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Statistics | |

| Nickname(s) | "Gidae" (English: Anticipation) |

| Weight(s) | Lightweight |

| Nationality | South Korean |

| Born | Lee Deokgu July 29, 1955[1] Goseong County, Gangwon, South Korea |

| Died | November 18, 1982 (aged 27) Paradise, Nevada, U.S.[1] |

| Stance | Southpaw |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 20 |

| Wins | 17 |

| Wins by KO | 8 |

| Losses | 2 |

| Draws | 1 |

| No contests | 0 |

| Kim Duk-koo | |

| Hangul | 김득구 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 金得九 |

| Revised Romanization | Gim Deuk-gu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kim Tŭk-ku |

Early life and education

Kim was born in Gangwon Province, South Korea, 100 miles east of Seoul, the youngest of five children. His father died when he was two and his mother married three more times. Kim grew up poor.[2] He worked odd jobs such as a shoe-shining boy and a tour guide before getting into boxing in 1976.

Career

After compiling a 29–4 amateur record, he turned professional in 1978. In February 1982, he won the Orient and Pacific Boxing Federation lightweight title and became the World Boxing Association's number 1 contender.[1] Kim carried a 17–1–1 professional record into the Mancini fight[3] and had won 8 bouts by KO before flying to Las Vegas as the world's (WBA) number 1 challenger to world lightweight champion Mancini. However, he had fought outside of South Korea only once before, in the Philippines. It was his first time ever fighting in North America.[4]

Mancini match

Kim was lightly regarded by the U.S. boxing establishment,[5] but not by Ray Mancini, who believed the fight would be a "war".[1] Kim struggled to lose weight in the days prior to the bout so that he could weigh in under the lightweight's 135-pound limit. Before the fight, Kim was quoted as saying "Either he dies or I die."[1] He wrote the message "live or die" on his Las Vegas hotel lampshade only days before the bout (a mistaken translation led to "kill or be killed" being reported in the media).[1]

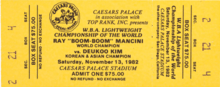

Mancini and Kim met in an arena outside Caesars Palace on November 13, 1982. They went toe to toe for a good portion of the bout, to the point that Mancini briefly considered quitting.[5] Kim tore open Mancini's left ear and puffed up his left eye, and Mancini's left hand swelled to twice its normal size.[3] After the fight Mancini's left eye would be completely closed.[1] However, by the latter rounds, Mancini began to dominate, landing many more punches than Kim. In the 11th he buckled Kim's knees.[1] In the beginning of the 13th round Mancini charged Kim with a flurry of 39 punches but had little effect. Sugar Ray Leonard (working as one of the commentators of the fight) said Kim came right back very strong. Leonard later declared the round to be closely contested.[6] When the fighters came out for the 14th round, Mancini charged forward and hit Kim with a right. Kim reeled back, Mancini missed with a left, and then Mancini hit Kim with another hard right hand. Kim went flying into the ropes, his head hitting the canvas. Kim managed to rise unsteadily to his feet, but referee Richard Green stopped the fight and Mancini was declared the winner by TKO nineteen seconds into the 14th round.[3] Ralph Wiley of Sports Illustrated, covering the fight, would later recall Kim pulling himself up the ropes as he was dying as "one of the greatest physical feats I had ever witnessed".[1]

Minutes after the fight was over, Kim collapsed into a coma and was removed from the Caesars Palace arena on a stretcher and taken to the Desert Springs Hospital. At the hospital, he was found to have a subdural hematoma consisting of 100 cubic centimeters of blood in his skull.[1] Emergency brain surgery was performed at the hospital to try to save him, but Kim died five days after the bout, on November 18. The neurosurgeon said it was caused by one punch.[3] The week after, Sports Illustrated published a photo of the fight on its cover, under the heading Tragedy in the Ring.[7] The profile of the incident was heightened by the fight having been televised live by CBS in the United States.

Kim had never fought a 15-round bout before. In contrast, Mancini was much more experienced at the time. He had fought 15-round bouts thrice and gone on to round 14 once before. Kim compiled a record of 17 wins with two losses and one draw. Eight of Kim's wins were knockouts.

Aftermath of Kim's death

Mancini went through a period of reflection, as he blamed himself for Kim's death. After friends helped him by telling him that it was just an accident, Mancini went on with his career, though still haunted by Kim's death. His promoter, Bob Arum, said Mancini "was never the same" after Kim's death. Two years later, Mancini lost his title to Livingstone Bramble.[8]

Four weeks after the fatal fight, the Mike Weaver vs. Michael Dokes fight at the same Caesars Palace venue ended with a technical knockout declared 63 seconds into the fight. Referee Joey Curtis admitted to stopping the fight early under orders of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, which required referees to be aware of a fighter's health, in light of the Mancini–Kim fight, and a rematch was ordered.

Kim's mother flew from South Korea to Las Vegas to be with her son before the life support equipment was turned off. Three months later, she committed suicide by drinking a bottle of pesticide.[2] The bout's referee, Richard Green, committed suicide via self-inflicted gunshot wound on July 1, 1983.[9]

Kim left behind a fiancée, Lee Young-Mee, despite rules against South Korean boxers having girlfriends.[1] At the time of Kim's death, Lee was pregnant with their son, Kim Chi-Wan, who was born in July 1983. Kim Chi-Wan became a dentist.[2] In 2011, Kim Chi-Wan and his mother had a meeting with Ray Mancini as part of a documentary on the life of Mancini called The Good Son.[1][10]

In popular culture, the San Francisco-based band Sun Kil Moon’s first album, Ghosts of the Great Highway, has three tracks named after boxers, including a song about Duk-koo Kim which references the Mancini fight; Sports Illustrated included the song on its list of greatest songs about sports.[11]

Boxing rule changes

The Nevada State Athletic Commission proposed a series of rule changes as a result, announcing it before a December 10 match between Michael Dokes and Mike Weaver that would in itself be disputed because of what officials were informed before the fight. The break between rounds was initially proposed to go from 60 to 90 seconds (but it was later rescinded). The standing eight count (which allows a knockdown to be called even if the boxer is not down, but on the verge of being knocked down) was imposed, and new rules regarding suspension of licence were imposed (45 days after a knockout loss).[12]

The WBC, which was not the fight's sanctioning organization, announced during its annual convention of 1982 that many rules concerning fighters' medical care before fights needed to be changed. One of the most significant was the WBC's reduction of title fights from 15 rounds to 12. The WBA and the IBF followed the WBC in 1987. When the WBO was formed in 1988, it immediately began operating with 12-round world championship bouts.[8]

In the years after Kim's death, new medical procedures were introduced to fighters' pre-fight checkups, such as electrocardiograms, brain tests, and lung tests. As one boxing leader put it, "A fighter's check-ups before fights used to consist of blood pressure and heartbeat checks before 1982. Not anymore."[13]

Professional boxing record

| Res. | Record | Opponent | Type | Rd., Time | Date | Location | Notes |

| Loss | 17–2–1 | TKO | 14 (15) 0:19 | November 13, 1982 | Caesars Palace, Nevada, U.S. | For WBA Lightweight title; Kim died 4 days later | |

| Win | 17–1–1 | TKO | 4 (12) | July 18, 1982 | Seoul, South Korea | OPBF lightweight title | |

| Win | 16–1–1 | UD | 10 (10) | June 21, 1982 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 15–1–1 | UD | 12 (12) | May 30, 1982 | Seoul, South Korea | OPBF lightweight title | |

| Win | 14–1–1 | KO | 1 (12) | April 4, 1982 | Seoul, South Korea | OPBF lightweight title | |

| Win | 13–1–1 | UD | 12 (12) | February 28, 1982 | Seoul, South Korea | OPBF lightweight title | |

| Win | 12–1–1 | TKO | 3 (10) | December 12, 1981 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 11–1–1 | KO | 4 (10) | September 9, 1981 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 10–1–1 | PTS | 10 (10) | August 16, 1981 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 9–1–1 | TKO | 4 (10) | April 22, 1981 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 8–1–1 | PTS | 10 (10) | December 6, 1980 | Seoul, South Korea | Lightweight title | |

| Win | 7–1–1 | TKO | 8 (10) | July 16, 1980 | Metro Manila, Philippines | ||

| Win | 6–1–1 | KO | 8 (8) | June 21, 1980 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Draw | 5–1–1 | PTS | 8 (8) | February 26, 1980 | Pusan, South Korea | ||

| Win | 5–1 | PTS | 4 (4) | October 6, 1979 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 4–1 | PTS | 4 (4) | September 1, 1979 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 3–1 | KO | 1 (4) | March 25, 1979 | Ulsan, South Korea | ||

| Loss | 2–1 | PTS | 4 (4) | December 9, 1978 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 2–0 | PTS | 4 (4) | December 8, 1978 | Seoul, South Korea | ||

| Win | 1–0 | PTS | 4 (4) | December 7, 1978 | Seoul, South Korea | Professional debut | |

See also

- Tan Teng Kee (died 1935), reported as one of the early boxing fatalities outside of Singapore

- Benny Paret (1937–1962), Cuban boxer died sustained in the ring lost to Emile Griffith

- Davey Moore (1933–1963), another boxer who famously died from an injury sustained in the ring

- Choi Yo-sam (1972–2008), former world champion who died after winning his final fight

- Johnny Owen (1956–1980), Welsh boxer never regained consciousness after being knocked out in the twelfth round of a WBC World Bantamweight title fight against Lupe Pintor

- List of deaths due to injuries sustained in boxing

References

- Kriegel, Mark (September 16, 2012), "A Step Back", The New York Times

- Shapiro, Michael (April 27, 1987). "Remembering Duk Koo Kim". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "Then All The Joy Turned To Sorrow", Ralph Wiley, Sports Illustrated, November 22, 1982

- "Donaire vs. Nishioka Photos: Nonioto Donaire LA arrival - Boxing News". Eastsideboxing.com. October 9, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Video on YouTube

- "Twenty-five years is a long time to carry a memory". Sports.espn.go.com. November 13, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "'It was a brutal fight' | Las Vegas Review-Journal". Lvrj.com. November 13, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "(Yonhap Feature) New documentary about Kim Duk-koo set for release 30 years after his death". Yonhap News. August 17, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Sports Illustrated's Ultimate Playlist". SI.com. June 28, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- Katz, Michael (December 12, 1982). "Referee Defends His Decision". New York Times (1982-12-12). New York Times. NYT. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Archived September 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Boxing record for Kim Duk-koo from BoxRec

External links

- Boxing record for Kim Duk-koo from BoxRec

- Footage of the Mancini-Kim Bout on YouTube

- "Duk Koo Kim". Professional Boxer. Find a Grave. March 31, 2004. Retrieved August 19, 2011.