Killygorman

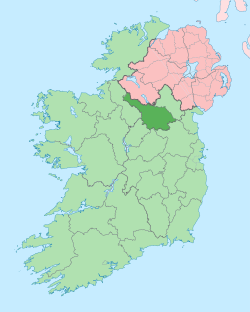

Killygorman (Irish derived place name, Coill Uí Ghormáin meaning 'The Wood of O’Gorman'[1]) is a townland in the civil parish of Kildallan, barony of Tullyhunco, County Cavan, Ireland.

.jpg)

Geography

Killygorman is bounded on the west by Derrinlester and Doogary townlands, on the east by Drumlarah and Evlagh Beg townlands, on the south by Tonaloy townland and on the north by Greaghacholea townland. Its chief geographical features are Killygorman Hill which rises to 350 feet, small streams, spring wells and brick holes. Killygorman is traversed by the regional R199 road (Ireland), minor public roads and rural lanes. The townland covers 300 acres,[2].

History

The Ulster Plantation Baronial map of 1609 depicts the name as Keilygarrama.[3][4] A 1615 lease spells the name as Killegarnan. A 1630 inquisition spells the name as Cregnakillegorman. The 1652 Commonwealth Survey spells the townland as Killegarmen.

From medieval times up to the early 1600s, the land belonged to the McKiernan Clan. In the Plantation of Ulster in 1609 the lands of the McKiernans were confiscated, but some were later regranted to them. In the Plantation of Ulster grant dated 4 June 1611, King James VI and I granted 400 acres (160 hectares) or 7 poles (a poll is the local name for townland) of land in Tullyhunco at an annual rent of £4 5s. 4d., to Bryan McKearnan, gentleman, comprising the modern-day townlands of Clontygrigny, Cornacrum, Cornahaia, Derrinlester, Dring, Drumlarah, Ardlougher and Kiltynaskellan.[5] Under the terms of the grant, McKearnan was obliged to build a house on this land. The said Brian 'Bán' Mág Tighearnán (anglicized 'Blonde' Brian McKiernan) was chief of the McKiernan Clan of Tullyhunco, County Cavan, Ireland from 1588 until his death on 4 September 1622. In a visitation by George Carew, 1st Earl of Totnes in autumn 1611, it was recorded, McKyernan removed to his proportion and is about building a house.[6] On 23 March 1615, Mág Tighearnán granted a lease on these lands to James Craig.[7] On 14 March 1630, an Inquisition of King Charles I of England held in Cavan Town stated that Brian bane McKiernan died on 4 September 1622, and his lands comprising seven poles and three pottles in Clonkeen, Clontygrigny, Cornacrum, Derrinlester, Dring townland, Killygorman, Kiltynaskellan and Mullaghdoo, Cavan went to his nearest relatives. The most likely inheritors being Cahill, son of Owen McKiernan; Brian, son of Turlough McKiernan and Farrell, son of Phelim McKiernan, all aged over 21 and married.[8] On 26 April 1631 a re-grant was made to Sir James Craige, which included the lands of Killegarnan, which also included several sub-divisions in the townland called Aghowleg, Aghemore, Gillegarnan, Monenemullagh and Carnincale.[9] In the Irish Rebellion of 1641 the rebels occupied the townland. Sir James Craig died in the siege of Croaghan Castle on 8 April 1642. His land was inherited by his brother John Craig of Craig Castle, County Cavan and of Craigston, County Leitrim, who was chief doctor to both King James I and Charles I.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641 concluded, the rebels vacated the land and the 1652 Commonwealth Survey lists the townland as belonging to Lewis Craig and describes it as wasteland. In the Hearth Money Rolls compiled on 29 September 1663[10] there were two Hearth Tax payers in Killegarman- Edmond McKiernan, Thomas O Senan and Brian Murtho.

The 1790 Cavan Carvaghs list spells the townland name as Killygorman.[11]

In the 19th century the landlord of Killygorman was the Reverend Francis Saunderson (b.1786), who was Church of Ireland rector of Kildallan from 1828 until his death on 22 December 1873.The 1938 Dúchas folklore collection states- Rector Saunderson was landlord of Killygorman, Derrinlester & Pottle. His Catholic tenants were always in dread of being evicted as he often threatened to do so if they did not obey his commands. He tried as far as he could to prosletyze but did not succeed. His wife Lady Saundrerson, had a school built beside the entrance to their demesne.[12]

The Tithe Applotment Books for 1827 list fourteen tithepayers in the townland.[13]

The Killygorman Valuation Office books are available for April 1838.[14][15][16]

Griffith's Valuation of 1857 lists twenty-nine landholders in the townland.[17]

Folklore collected at Killygorman National School in 1938 is available at-[18]

Matthew Gibney the Roman Catholic bishop of Perth, Australia was a native of Killygorman.[19]

Census

| Year | Population | Males | Females | Total Houses | Uninhabited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 200 | 106 | 94 | 35 | 1 |

| 1851 | 161 | 78 | 83 | 29 | 3 |

| 1861 | 70 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 0 |

| 1871 | 79 | 42 | 37 | 16 | 0 |

| 1881 | 79 | 42 | 37 | 17 | 2 |

| 1891 | 68 | 38 | 30 | 16 | 2 |

In the 1901 census of Ireland, there were sixteen families listed in the townland.[20]

In the 1911 census of Ireland, there were fifteen families listed in the townland.[21]

Antiquities

- Killygorman National School. In 1842 Killygorman School (Roll Number 2371) was mixed and had an attendance of 100 boys and 50 girls.[22] The headmaster was Michael Freehill. On 21 December 1849 it was stated- Mr. Michael FREEHIL, teacher of Killegorman National School, near Killeshandra, in this county, has been promoted to the first division of first-class National School teachers, at a salary of £30. per annum; and that he has received also, as marks of the Commissioners' approbation, Lord Morpeth's premium and two first-class premiums in succession for the order, cleanliness, and improvement observable in his pupils and School-house.[23] In 1854 the school was split into Killygorman Boys' School (Roll Number 2371) with 74 pupils and Killygorman Girls' School (Roll Number 3547) with 72 pupils.[24] In 1862 the headmaster of the boys school was Philip Cahill, a Roman Catholic and there were 57 male pupils, all Roman Catholic. In 1862 the headmistress of the girls school was Mrs Bridget Hayden, a Roman Catholic and there were 63 female pupils, one was a Protestant and the rest were Roman Catholic.[25] In 1874 the headmaster of the boys' school was John Maguire and it had 81 pupils and the headmistress of the girls' school was still Mrs Bridget Hayden and it had 87 pupils.[26] In 1890 the boys' school had 109 pupils and the girls' school had 82 pupils.[27]

- Royal Irish Constabulary Barracks

References

- "Placenames Database of Ireland - Killygorman". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "IreAtlas". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "(Dronge map)". cavantownlands.com. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland. - (Dublin 1800 ... Books.google.co.uk. p. 211. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts: Miscellaneous papers: The book of Howth ... - Lambeth Palace Library, George Carew Earl of Totnes. Books.google.co.uk. p. 96. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Inquisitionum in Officio Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Asservatarum ... Books.google.co.uk. p. 3. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- The Hearth Money Rolls for the Baronies of Tullyhunco and Tullyhaw, County Cavan, edited by Rev. Francis J. McKiernan, in Breifne Journal. Vol. I, No. 3 (1960), pp. 247-263

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1901". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911". Retrieved 19 October 2016.