Killaghaduff

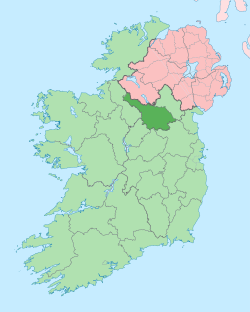

Killaghaduff (Irish derived place name, either Cill Átha Dhuibh, meaning ‘The Church of the Black Ford’ or Coill Achadh Dhuibh, meaning ‘The Wood of the Black Ford’ or Cill Achadh Dhuibh, meaning ‘The Church of the Black Field’ or Coill Achadh Dhuibh, meaning ‘The Wood of the Black Field’) is a townland in the civil parish of Kinawley, barony of Tullyhaw, County Cavan, Ireland.[1]

Geography

Killaghaduff is bounded on the north by Gortacashel townland, on the south by Tircahan townland, on the west by Furnaceland and Gorteen (Kinawley) townlands and on the east by Drumod Glebe, Gortlaunaght, Gortnaderrylea and Tonyquin townlands. Its chief geographical features are a hill, the Blackwater river which later joins the River Cladagh (Swanlinbar), streams, woods, a quarry, rocky outcrops, spring wells and dug wells, one of which is a Holy Well.[2] Killaghaduff is traversed by minor public roads and rural lanes. The townland covers 96 statute acres.[3]

History

In medieval times Killaghaduff formed part of a ballybetagh, owned by the McGovern clan, spelled (variously) Aghycloony, Aghcloone, Nacloone, Naclone and Noclone (Irish derived place name Áth Chluain, meaning ‘The Ford of the Meadow’). However Killaghaduff was owned by the Roman Catholic Church and so its history belongs to the ecclesiastical history of the parish. It would have belonged to the parish priest and the erenach family rather than to the McGovern chief. In the 16th century these ecclesiastical lands in Killaghaduff were seized in the course of the Reformation in Ireland and kept initially by the English monarch and then eventually granted to the Anglican Bishop of Kilmore. The townland was also called Templedowa or Tampledowne (Irish derived place name Teampall Dhuibh, meaning ‘The Black Church’, which is basically the same meaning as Killaghaduff) and Cardragh, Croderagh or Crodragh (Irish derived place name Cruach Doire, meaning ‘The Hill of the Oakwood’). The church had two different rights, one was ownership of the church lands (both termon lands and the site of the church and graveyard) and the other was ownership of the church tithes (also called the rectorial tithes or the rectory) which were a tenth of all the produce of the parish not owned by the church. These rights were often owned by different people and so had a different history, as set out below.

Church and Termon lands

An Inquisition held in Cavan Town on 19 September 1590 found the termon or hospital lands of Templedowa to consist of one poll of land at a yearly value of 12 pence.[4]

By grant dated 6 March 1605, along with other lands, King James VI and I granted a lease of the farm, termons or hospitals of Tampledowne containing 1 poll for 21 years at an annual rent of 2 shillings and six pence to Sir Garret Moore, 1st Viscount Moore.[5]

By grant dated 10 August 1607, along with other lands, King James VI and I granted a further lease of the farms, termons or hospitals of Templedowa containing 1 poll for 21 years at an annual rent of 3 shillings & 3 pence to the aforesaid Sir Garret Moore, 1st Viscount Moore of Mellifont Abbey, County Louth.

A survey held by Sir John Davies (poet) at Cavan Town on 6 September 1608 stated that- Killadough contayning 1 polle lyeinge neere the parish church of Killadough, the rectory is appropriate to the said abbay of Kels. There is a viccar endowed.[6]

An Inquisition held in Cavan Town on 25 September 1609 found the termon land of Killaghduffe to consist of one poll of land, out of which the Bishop of Kilmore was entitled to a rent 12 pence per annum and that the parish of Killaghduffe containinge one ballibetagh and a half, the parsonage whereof is impropriate to the late abbey of Kelles, the vicarage collative and the tithes paid in kinde, two third partes of the tithes are paid to the said late abbey of Kells in right of the said impropriation, and the other third parte to the viccar. The Inquisition then granted the lands to the Protestant Bishop of Kilmore.[7]

By a deed dated 6 April 1612, Robert Draper, the Anglican Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh granted a joint lease of 60 years over the termons or herenachs of, inter alia, 1 poll in Killaghedowe to Oliver Lambart, 1st Lord Lambart, Baron of Cavan, of Kilbeggan, County Westmeath and Sir Garret Moore, 1st Viscount Moore, of Mellifont Abbey, County Louth.[8]

By deed dated 17 July 1639, William Bedell, the Anglican Bishop of Kilmore, extended the above lease of Killaghedow to Oliver Lambert's son, Charles Lambart, 1st Earl of Cavan.

Rectorial Tithes

The rectorial tithes were split between the local parish priest who received 1/3 and the Abbey of Kells who received 2/3, from medieval times until they were seized in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. A list of the rectories owned by King Henry VIII of England in 1542 included Cardragh which he seized from Kells Abbey.[9]

On 14 January 1587 Elizabeth I of England granted the said rectory of Crodragh to Garret (otherwise Gerald) Fleming of Cabragh.[10]

On 30 October 1603 the aforementioned Gerrald Fleming surrendered the rectory of Crodragh to King James VI and I and it was regranted to him for a term of 21 years.[11]

By grant dated 22 December 1608, along with other lands, King James VI and I granted a lease of the rectories, churches, or chapels formerly belonging to Kells Abbey, including Crodraghe to Gerald Fleminge of Cabragh, County Cavan.[12]

On 4 March 1609 the aforementioned Gerrald Fleming leased the rectory of Crodragh to his son James Fleming and Walter Talbot of Ballyconnell.[13] On 8 June 1619 the aforesaid James Fleming and Walter Talbot were pardoned by King James VI and I for obtaining the said rectory of Clodragh without getting a licence from the king.

An Inquisition held at Cavan on 19 October 1616 stated that the aforementioned Gerald Fleming died on 5 April 1615 and his son Thomas Fleming (born 1589) succeeded to the rectorial tithes of Crodragh.[14]

Maps

The 1609 Baronial Map depicts Killaghaduff church with an Irish round tower as part of Naclone.[15]

The 1658 Down Survey map depicts the townland as Killahadough and is marked with a + to indicate Church Lands.[16]

18th century onwards

The 1790 Cavan Carvagh list spells the name as Killaghdow.[17]

The 1821 Census of Ireland spells the name as Killaugaduff and states- Excellent land with a burial place on the farm.[18]

The 1825 Tithe Applotment Books spell the name as Killaduff.[19]

The 1836 Ordnance Survey Namebooks state- the ruins of an old church and grave yard. At the south corner of the grave yard there is an old Danish fort: lime is procured on the ground and is used for manure. The soil is light.

The Killaghaduff Valuation Office Field books are available for 1838-1840.[20][21]

Griffith's Valuation lists six landholders in the townland.[22]

The landlord of Killaghaduff in the 1850s was Nicholas Ellis.

Census

| Year | Population | Males | Females | Total Houses | Uninhabited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 35 | 17 | 18 | 5 | 0 |

| 1851 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 0 |

| 1861 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| 1871 | 23 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 0 |

| 1881 | 23 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 0 |

| 1891 | 31 | 15 | 16 | 4 | 0 |

In the Census of Ireland 1821 there were three households in the townland.[23][24]

In the 1901 census of Ireland, there were four families listed in the townland.[25]

In the 1911 census of Ireland, there were eight families listed in the townland.[26]

Antiquities

- The ruins of a medieval Roman Catholic Church and Graveyard (which is still used). Taylor and Skinner's map drawn in summer 1777 shows it as "Church Ruins".[27] In the 18th century there was a Mass Rock in the townland which was later replaced with a thatched chapel in a Mass Garden in the adjoining townland of Gortacashel. In 1828 the Roman Catholic chapel was relocated to Hawkswood townland in the town of Swanlinbar. The 'Archaeological Inventory of County Cavan' (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1995), Site no. 1658, describes Killaghaduff ruins as Ruined remains of a church comprising ivy-clad E gable (L c. 7.5m) with base batter. Situated within a roughly rectangular graveyard (dims. 54m E-W x 52m N-S). E gable contains a square-framed, double-cusped window with hood-moulding and upturned stops. Above it is a second window with similar jambs, set off centre. (Davies 1948, p.110[28]). The 1938 Dúchas Collection gives several traditions about the church and graveyard.[29][30][31][32][33][34] The gravestone inscriptions are available online.[35][36][37]

- A Holy Well. The 1938 Dúchas Collection gives a description.[34]

- A medieval earthen ringfort. The 'Archaeological Inventory of County Cavan' (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1995), Site no. 766, describes it as Davies (ITA Survey 1946) described it as a roughly circular area (int. dims. 21m N-S; 19m E-W) enclosed by a slight earthen bank and a poorly preserved fosse. Possible hut site within enclosed area at north. Bordered by a field boundary from W-NNW, and by a graveyard from NNW-N-NNE. Although largely levelled, outline of rath may still be traced.

- A lime-kiln. The 1938 Dúchas Collection gives traditions about lime manufacturing in the townland.[38][39]

References

- "Placenames Database of Ireland". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "IreAtlas". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Archdall, Mervyn (14 September 1873). Monasticon Hibernicum: or, a history of the abbeys, priories, and other religious houses in Ireland; interspersed with memoirs of their several founders and benefactors, and of their abbots and other superiors, to the time of their final suppression. W. B. Kelly. p. 71 – via Internet Archive.

Kilfert.

- gh

- Crodraghe%20Garret&f=false

- The National Archives (30 September 2009). "Map of Tullyhaw, County Cavan (MPF 1/58)" (PDF). National Archives Dublin. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "The Carvaghs: A List Of The Several Baronies And Parishes in the County Of Cavan" (PDF). 7 October 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "007246490_00335" (PDF). 11 December 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "004625688/004625688_00054.pdf" (PDF). 4 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Griffith's Valuation". askaboutireland.ie. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1901". census.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911". census.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 6 July 2019.