Kiang

The kiang (Equus kiang) is the largest of the wild asses. It is native to the Tibetan Plateau, where it inhabits montane and alpine grasslands. Its current range is restricted to plains of the Tibetan plateau and Ladakh, India ,[3][4] and northern Nepal along the Tibetan border.[5] Other common names for this species include Tibetan wild ass, khyang and gorkhar.[6][7] Travellers' accounts of the kiang are one inspiration for the unicorn.

| Kiang[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Subgenus: | Asinus |

| Species: | E. kiang |

| Binomial name | |

| Equus kiang Moorcroft, 1841 | |

| |

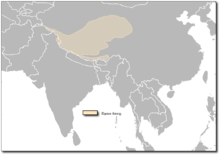

| Range map | |

Characteristics

_from_the_book_entitled%2C_The_great_and_small_game_of_India%2C_Burma%2C_and_Tibet_(1900)_(cropped).jpg)

The kiang is the largest of the wild asses, with an average height at the withers of 13.3 hands (55 inches, 140 cm). They range from 132 to 142 cm (52 to 56 in) high at the withers, with a body 182 to 214 cm (72 to 84 in) long, and a tail of 32 to 45 cm (13 to 18 in). Kiangs have only slight sexual dimorphism, with the males weighing from 350 to 400 kg (770 to 880 lb), while females weigh 250 to 300 kg (550 to 660 lb). They have a large head, with a blunt muzzle and a convex nose. The mane is upright and relatively short. The coat is a rich chestnut colour, darker brown in winter and a sleek reddish brown in late summer, when the animal moults its woolly fur. The summer coat is 1.5 cm long and the winter coat is double that length. The legs, underparts, end of the muzzle, and the inside of the ears are all white. A broad, dark chocolate-coloured dorsal stripe extends from the mane to the end of the tail, which ends in a tuft of blackish brown hairs.[8]

Evolution

The genus Equus, which includes all extant equines, is believed to have evolved from Dinohippus, via the intermediate form Plesippus. One of the oldest species is Equus simplicidens, described as zebra-like with a donkey-shaped head. The oldest fossil to date is ~3.5 million years old from Idaho, USA. The genus appears to have spread quickly into the Old World, with the similarly aged Equus livenzovensis documented from western Europe and Russia.[9]

Molecular phylogenies indicate the most recent common ancestor of all modern equids (members of the genus Equus) lived ~5.6 (3.9–7.8) mya. Direct paleogenomic sequencing of a 700,000-year-old middle Pleistocene horse metapodial bone from Canada implies a more recent 4.07 Myr before present date for the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) within the range of 4.0 to 4.5 Myr BP.[10] The oldest divergencies are the Asian hemiones (subgenus E. (Asinus), including the kulan, onager, and kiang), followed by the African zebras (subgenera E. (Dolichohippus), and E. (Hippotigris)). All other modern forms including the domesticated horse (and many fossil Pliocene and Pleistocene forms) belong to the subgenus E. (Equus) which diverged ~4.8 (3.2–6.5) million years ago.[11]

Taxonomy

The kiang is closely related to the onager (Equus hemionus), and in some classifications it is considered a subspecies, E. hemionus kiang. Molecular studies, however, indicate that it is a distinct species.[12] An even closer relative, however, may be the extinct Equus conversidens of Pleistocene America,[13] to which it bears a number of striking similarities; however, such a relationship would require kiangs to have crossed Beringia during the Ice Age, for which little evidence exists. Kiangs can crossbreed with onagers, horses, donkeys, and Burchell's zebras in captivity, although, like mules, the resulting offspring are sterile. Kiangs have never been domesticated.[8]

Distribution and habitat

Kiangs are found on the Tibetan Plateau, between the Himalayas in the south and the Kunlun Mountains in the north. This restricts them almost entirely to China, but numbers up to 2500 to 3000 are found across the borders in the Ladakh and Sikkim regions of India, and smaller numbers along the northern frontier of Nepal.[14]

Three subspecies of kiangs are currently recognised:[1][8][14]

- E. k. kiang — western kiang (Tibet, Ladakh, southwestern Xinjiang)

- E. k. holdereri — eastern kiang (Qinghai, southeastern Xinjiang)

- E. k. polyodon — southern kiang (southern Tibet, Nepalese border)

The eastern kiang is the largest subspecies; the southern kiang is the smallest. The western kiang is slightly smaller than the eastern and also has a darker coat. However, no genetic information confirms the validity of the three subspecies, which may simply represent a cline, with gradual variation between the three forms.[2][14]

Kiangs inhabit alpine meadows and steppe country between 2,700 and 5,300 m (8,900 and 17,400 ft) elevation. They prefer relatively flat plateaus, wide valleys, and low hills, dominated by grasses, sedges, and smaller amounts of other low-lying vegetation. This open terrain, in addition to supplying them with suitable forage absent in the more arid regions of central Asia, may make it easier for them to detect, and flee from, predators.[15]

Behavior

Like all equids, kiangs are herbivores, feeding on grasses and sedges, especially Stipa, but also including other local plants such as bog sedges, true sedges, and meadow grasses. When little grass is available, such as during winter or in the more arid margins of their native habitat, they have been observed eating shrubs, herbs, and even Oxytropis roots, dug from the ground. Although they do sometimes drink from waterholes, such sources of water are rare on the Tibetan Plateau, and they likely obtain most of their water from the plants they eat, or possibly from snow in winter.[8]

Their only real predator other than humans is the Himalayan wolf. Kiangs defend themselves by forming a circle, and with heads down, kick out violently. As a result, wolves usually attack single animals that have strayed from the group.[16] Kiangs sometimes gather together in large herds, which may number several hundred individuals. However, these herds are not permanent groupings, but temporary aggregations, consisting either of young males only, or of mothers and their foals. Older males are typically solitary, defending a territory of about 0.5 to 5 km2 (0.19 to 1.93 sq mi) from rivals, and dominating any local groups of females. Territorial males sometimes become aggressive towards intruders, kicking and biting at them, but more commonly chase them away after a threat display that involves flattening the ears and braying.[8]

Reproduction

Kiangs mate between late July and late August, when older males tend reproductive females by trotting around them, and then chasing them prior to mating. The length of gestation has been variously reported as seven to 12 months, and results in the birth of a single foal. Females are able to breed again almost immediately after birth, although births every other year are more common. Foals weigh up to 35 kg (77 lb) at birth, and are able to walk within a few hours. The age of sexual maturity is unknown, although probably around three or four years, as it is in the closely related onager. Kiang live for up to 20 years in the wild.[8]

Travellers' accounts

Natural historian Chris Lavers points to travellers' tales of the kiang as one source of inspiration for the unicorn, first described in Indika by the Ancient Greek physician Ctesias.[17]

Ekai Kawaguchi, a Japanese monk who traveled in Tibet from July, 1900 to June 1902, reported:

- "As I have already said, khyang is the name given by the Tibetans to the wild horse of their northern steppes. More accurately it is a species of ass, quite as large in size as a large Japanese horse. In color it is reddish brown, with black hair on the ridge of the back and black mane and with the belly white. To all appearance it is an ordinary horse, except for its tufted tail. It is a powerful animal, and it is extraordinarily fleet. It is never seen singly, but always in twos or threes, if not in a herd of sixty or seventy. Its scientific name is Equus hemionis, but is for the most part called by its Tibetan name, which is usually spelled khyang in English. It has a curious habit of turning round and round, when it comes within seeing distance of a man. Even a mile and a quarter away, it will commence this turning round at every short stage of its approach, and after each turn it will stop for a while, to look at the man over its own back, like a fox. Ultimately it comes up quite close. When quite near it will look scared, and at the slightest thing will wheel round and dash away, but only to stop and look back. When one thinks it has run far away, it will be found that it has circled back quite near, to take, as it were, a silent survey of the stranger from behind. Altogether it is an animal of very queer habits."[18]

Thubten Jigme Norbu, the elder brother of Tenzin Gyatso the 14th Dalai Lama, reporting on his trip from Kumbum Monastery in Amdo to Lhasa in 1950, said:

- "The kyangs or wild asses, live together in smaller groups, each headed by a stallion, lording it over anything from 10 to 50 mares. I was struck by the noble appearance of these beasts, and in particular, by the beautiful line of head and neck. Their coat is light brown on the back and whitish below the belly, and their long, thin tails are almost black; the whole representing excellent camouflage against their natural background. They look wonderfully elegant and graceful when you see them darting across the steppes like arrows, heads stretched out and tails streaming away behind them in the wind. Their rutting season is in the autumn, and then the stallions are at their most aggressive as they jealously guard their harems. The fiercest and most merciless battles take place at this time of the year between the stallion installed and interlopers from other herds. When the battle is over, the victor, himself bloody and bruised from savage bites and kicks, leads off the mares in a wild gallop over the steppe.

- We would often see kyangs by the thousand spread over the hillsides and looking inquisitively at our caravan; sometimes they would even surround us, though keeping at some distance."[16]

References

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 632. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Shah, N.; St. Louis, A.; Huibin, Z.; Bleisch, W.; van Gruissen, J. & Qureshi, Q. (2008). "Equus kiang". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- In weasel land; Text and pictures by Sujatha Padmanabhan; Jan 10, 2004; The Hindu, India's National Newspaper

- Wild Ass sighted in Rajasthan villages along Gujarat; by Sunny Sebastian; Sep 13, 2009; The Hindu, India's National Newspaper

- Sharma, et al., 2004. Mapping Equus kiang (Tibetan Wild Ass) Habitat in Surkhang, Upper Mustang, Nepal. Mountain Research and Development. Vol 24(2): 149–156.

- Ladakh Physical, Statistical, and Historical Ladakh Physical, Statistical, and Historical by Alexander Cunningham

- Kiang: The Animal Facts Kiang: The Animal Facts

- St-Louis, A.; Côté, S. (2009). "Equus kiang (Perissodactyla: Equidae)". Mammalian Species. 835: 1–11. doi:10.1644/835.1.

- Azzaroli, A. (1992). "Ascent and decline of monodactyl equids: a case for prehistoric overkill" (PDF). Ann. Zool. Finnici. 28: 151–163.

- Orlando, L.; Ginolhac, A.; Zhang, G.; Froese, D.; Albrechtsen, A.; Stiller, M.; Schubert, M.; Cappellini, E.; Petersen, B.; et al. (4 July 2013). "Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse". Nature. 499 (7456): 74–8. doi:10.1038/nature12323. PMID 23803765.

- Weinstock, J.; et al. (2005). "Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Pleistocene horses in the New World: a molecular perspective". PLoS Biology. 3 (8): e241. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030241. PMC 1159165. PMID 15974804. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Ryder, O.A.; Chemnick, L.G. (1990). "Chromosomal and molecular evolution in Asiatic wild asses". Genetica. 83 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1007/BF00774690. PMID 2090563.

- Bennett, D.K. (1980). "Stripes do not a zebra make, part I: a cladistic analysis of Equus". Systematic Zoology. 29 (3): 272–287. doi:10.2307/2412662.

- Shah, N. (2002). Moehlman, P.D. (ed.). Equids: zebras, asses and horses. Status survey and conservation action plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. pp. 72–81.

- Harris, R.B.; Miller, D.J. (1995). "Overlap in summer habitats and diets of Tibetan Plateau ungulates". Mammalia. 59 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1515/mamm.1995.59.2.197.

- Tibet is My Country: Autobiography of Thubten Jigme Norbu, Brother of the Dalai Lama as told to Heinrich Harrer, pp. 151–152. First published in German in 1960. English translation by Edward Fitzgerald, published 1960. Reprint, with updated new chapter, (1986): Wisdom Publications, London. ISBN 0-86171-045-2.

- Lavers, Chris (2009): The Natural History of Unicorns, pp. 15–19. HarperCollins Publishers, New York. ISBN 978-0-06-087414-8

- Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): Three Years in Tibet, pp. 131, 133. Reprint: Book Faith India (1995), Delhi. ISBN 81-7303-036-7

Further reading

- Kiang - Equus kiang; IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group; Species Survival Groups ()

- Duncan, P. (ed.). 1992. Zebras, Asses, and Horses: an Action Plan for the Conservation of Wild Equids. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

External links

| Look up kiang in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Equus kiang. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Equus kiang |