Khaz’al Khan Ibn Haji Jabir Khan

Khaz'al bin Jabir bin Merdaw al-Ka'bi GCIE KCSI (Arabic: خزعل بن جابر بن مرداو الكعبي، Persian: شیخ خزعل) (18 August 1863 – 24 May 1936), Muaz us-Sultana, and Sardar-e-Aqdas (Most Sacred Officer of the Imperial Order of the Aqdas),[1] was the Ruler of Arabistan, the Sheikh of Mohammerah from the Kasebite clan of the Banu Ka'b, of which he was the Sheikh of Sheikhs,[2] the Overlord of the Mehaisan tribal confederation and the Ruler of the Shatt al-Arab. He was the fifth and youngest son of Haji Jabir Khan Ibn Merdaw, and his mother, Sheikha Noura, was the daughter of Talal Bin Alwan, the Sheikh of the powerful Bawi tribe. He was born on 18 August 1863, in the village Qout Al Zain in the district of Abu Khasib in Basra and he ascended to the throne on 2 June 1897 upon the death of his brother and predecessor, Sheikh Miz'al Khan ibn Haji Jabir Khan.

| Khaz'al Bin Jabir | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sheikh Khaz'al in military uniform | |||||

| Sheikh of Mohammerah | |||||

| Reign | June 1897 – April 1925 | ||||

| Predecessor | Miz'al Khan ibn Haji Jabir Khan | ||||

| Successor | Sheikhdom dissolved | ||||

| Born | 18 August 1863 Basra Vilayet, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 24 May 1936 (aged 72) Tehran, Imperial State of Iran | ||||

| Spouse | See

| ||||

| Issue | See

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Al Mirdaw | ||||

| Father | Haji Jabir Khan Ibn Merdaw | ||||

| Mother | Noura Bint Talal | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Historical background

On 2 June 1897, Khaz'al inherited the Emirate of Mohammerah. The Emirate, although within the Persian Empire, was autonomous and allowed to conduct its own affairs.

Throughout Khaz’al's reign (1897-1925), he was one of the most important political figures in the Persian Gulf and a prominent supporter of Britain's presence in the region. Although never formally a part of the British Empire, the Gulf had been effectively incorporated into the British imperial system since the early 19th century. The conclusion of treaties and agreements with the region's various tribal rulers was one of the central means by which Britain enforced its hegemonic presence, and Khaz’al was no exception to this trend.[3]

Indeed, Khaz’al actively fostered close relations with Britain in an attempt to gain their assurance that in the event of the Qajar Empire collapsing or being overthrown, Arabistan would be formally recognised by Britain as an independent state with him as its ruler.

After oil was discovered by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (the forerunner of BP) in Arabistan in 1908, Britain strengthened its ties to Khaz’al further. In 1910 he was made a Knight Commander of the Indian Empire. During his reign Sheikh Khaz'al held a percentage of shares in BP. Those shares were later taken by force by Reza Khan.

Khaz’al sought to prove his loyalty to Britain in return and he acted as a key ally throughout the First World War during which he suppressed a pro-Ottoman tribal uprising in his domains. Khaz'al was also the darling of many Sunnite Iraqi nationalists, who sought to foment dissent among Iran's Arab population by referring to Khuzestan as Arabestān and glorifying Khaz'al as its independent "Sultan".[4] Khaz'al became a strong candidate for the throne of Iraq, but later withdrew his candidacy in favour of Faisal I of Iraq.

The tribal leaders of the Bani Kaab, an Arab tribe which had originally come from the area of what is now Kuwait in the 16th century, had often been the Imperial-appointed tax farmers of Arabistan for many years after the fall of the Mush'ashaiya. The Bani Kaab were the largest and most powerful tribe in the province. In the early 19th century the Bani Kaab had dissolved into a number of rival clans that often clashed and feuded with each other.

Of these factions, the Muhaisin clan, led by Haji Jabir Khan Ibn Merdaw, became the strongest and under his leadership the Bani Kaab were reunified under a single authority, the capital of Arabistan being moved from the village of Fallahiyah to the flourishing port city of Mohammerah. Unlike previous rulers of Arabistan, Jabir maintained law and order, and established Mohammerah as a free port and sheikhdom, of which he was Sheikh. Jabir also became the Imperial-appointed governor-general of the province.

Rise to power

After Jabir's death in 1881, his elder son, Maz'al, took over as tribal leader and Sheikh of Mohammerah, as well as the provincial governor-general, which was confirmed by an Imperial firman (executive order). However, in June 1897 Maz'al was killed. Some accounts state that he was assassinated by his younger brother,[5] Khaz'al, while others state that this was done by a palace guard under orders from Khaz'al.

Thereafter Khaz'al assumed his position as Sheikh of Mohammerah, proclaiming himself not only the leader of the Bani Kaab, but also the ruler of the entire province. He then appointed his sons to the governorships of the various cities, towns and villages within his control, including Naseriyeh.

Unlike his brother, Khaz'al had ambition. He had great vision for the future of Arabistan and the Arabs. His rule in Arabistan was "Supreme and unhindered".[6]

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The oil industry owed its early success to Sheikh Khaz'al.[7] Once oil was discovered in Masjed Soleyman in 1908, by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), later BP, Khaz'al's ties to Britain strengthened. In 1909, the British government asked Percy Cox, British resident to Bushehr, to negotiate an agreement with Khaz'al for APOC to obtain a site on Abadan Island for a refinery, depot, storage tanks, and other operations. The refinery was built and began operating in 1912. Khaz'al was knighted in 1910 and supported Britain in World War I.[8]

Following the discovery of oil in Arabistan-controlled territory, the British moved quickly to establish control over the vast oil resources in the province, which culminated in the foundation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in 1909. The British established a treaty with Khaz'al, whereby in exchange for their guaranteed support and protection against any external attack, he would also guarantee to maintain internal security and not interfere with the process of oil extraction. As part of the treaty they were given a monopoly of drilling in the province in return for an annual payment to Khaz'al, though the profits of the company vastly exceeded the annual payments.

Sheikh Khaz'al turns down the throne of Kuwait

In 1920, the Sheikh of Kuwait, Salim Al Mubarak Al Sabah, ambushed Ibn Saud's men over a border dispute between Kuwait and Najd. When Percy Cox was informed of this event, he sent a letter to Khaz'al offering the Kuwaiti throne to either him or one of his heirs, knowing that Khaz'al would be a wiser ruler. Khaz'al, who considered the Al Sabah as his own family, replied "Do you expect me to allow the stepping down of Al Mubarak from the throne of Kuwait? Do you think I can accept this?"[9] He then asked:

...even so, do you think that you have come to me with something new? Al Mubarak's position as ruler of Kuwait means that I am the true ruler of Kuwait. So there is no difference between myself and them, for they are like the dearest of my children and you are aware of this. Had someone else come to me with this offer, I would have complained about them to you. So how do you come to me with this offer when you are well aware that myself and Al Mubarak are one soul and one house, what affects them affects me, whether good or evil.[9]

Conflict with Reza Khan and downfall

In November 1923, when Khaz’al Khan had seen Ahmad Shah Qajar off, as he was crossing the border for Europe, the Emperor had told him about his fears of Reza Khan's ambitions in the same way as he had spoken openly to Percy Loraine. Then came the Shah's telegram of April 1924 about his loss of confidence in Reza Khan. In the following summer, Khaz’al brought together some regional magnates and tribal heads - the Vali of Poshtkuh, heads of the Khamseh federation of tribes, and many of the local Arab tribal leaders - in a coalition to resist Reza. They described themselves as the Committee of the Rising for Happiness, and sent telegrams and statements to Tehran. Their statements demanded constitutional government and the return of the Shah, who they said had been forced to remain in Europe. They also attacked military violations of the people's rights in the provinces, and ‘the massacres of Loristan’; demanded Reza Khan's dismissal; and described the Prince Regent, Ali Reza Khan Azod al-Molk, as the legitimate fount of authority. It was all in the name of the law, justice and the constitution, and ‘in the illustrious name of His Imperial Majesty Soltan Ahmad Shah, the constitutional monarch’. The committee sought to defend and protect Constitutionalism, and stop the traitors and criminals freely dispensing with it and re-establishing the apparatus of arbitrary rule and injustice once again ... and stop Reza Khan from trampling the principles of democratic government under foot by arbitrary government."[10]

The Prince Regent wrote an encouraging letter to Khaz’al, all in the name of the Shah and for protection of the constitution, and said that the bearer would discuss matters with the Shaikh in detail. The Shah and the court did not have the courage to commit themselves firmly to such a movement, but would go along with it if there was a very good change of success. Reza Khan subsequently sent him a bombastic tactless telegram, after which the Sheikh expressed his determination to overthrow Reza Khan or perish in the attempt. He declared that he would abandon his defensive measures only if Reza agreed to the following:

(i) to give written guarantees regarding the safety of life and property of those who were helping the Sheikh - especially the Bakhtiari Amir Mujahid. (ii) to withdraw all troops from Arabistan including Bebehan; (iii) to cancel the revenue settlement of the previous year and return to the pre-war basis; and (iv) to give a more specific confirmation of his firmans. On September 13th the British Political Resident was told to convey a message to Reza Khan to accept Khaz'al's conditions.[11]

In the meantime, the Political Resident had interviewed the Sheikh, his second son (Sheikh Abdul Hamid), the Bakhtiari Amir Mujahid and Colonel Riza Quli Khan (who had replaced Colonel Baqir Khan at Shushtar but who had apparently thrown in his lot with the Sheikh); all declared that no peace with Reza Khan was possible; the Sheikh had telegraphed to the Majlis explaining that his opposition was to Reza Khan personally and that it was hoped to persuade the Shah to return. On September 16 the Sheikh had also addressed a telegram to the foreign legations in Tehran in the nature of a proclamation against Reza Khan, who was described as a usurper and a transgressor of the Persian Empire.[11] Reza sent a telegram to Khaz’al that stating that he should either apologise to him and relent publicly, or take the full consequences. Khaz’al and his remaining associates could muster an army of 25,000 men, which was no less than Reza Khan could throw in the region at the time. In fact the army he had amassed at the foot of the Loristan elevations was 15,000 strong. But Khaz’al did not dare to go into action without British approval. The British government was in no mood to go to war on Khaz’al's behalf. Loraine convinced Khaz’al to desist and to apologize to Reza Khan. In return, he promised to intervene with Reza Khan to halt the advance of his troops into Arabistan. The Shaikh sent an apology, but, realizing that the danger had passed, Reza Khan paid little attention to Loraine's representations on the Shaikh's behalf. He let the troops pour into Arabistan, and demanded that Khaz’al should surrender unconditionally and go straight to Tehran. The Foreign Office was very unhappy at Reza Khan's intransigence. In the presence of Loraine, Khaz’al and Reza met and even swore an oath of friendship on the Qur’an.

After a short while, Reza broke all his pledges. In April 1925, he ordered one of his commanders, who had a friendly relationship with Khaz'al, to meet Khaz'al. The commander, General Fazlollah Zahedi, accompanied by several government officials, met with Khaz'al and spent an evening with him onboard his yacht, anchored in the Shatt al-Arab river by his palace in Failiyeh near the city of Mohammerah. Later that evening several gunboats, sent by Reza Khan, stealthily made their way next to the yacht, which was then immediately boarded by fifty Persian troops. The soldiers kidnapped[12] Khaz'al and took him by motorboat down the river to Mohammerah, where a car was waiting to take him to the military base in Ahwaz. From there he was taken to Dezful, along with his son and heir, and then to the city of Khorramabad in Lorestan, and then eventually to Tehran.[10]

Upon his arrival, Khaz'al was warmly greeted and well received by Reza Khan, who assured him that his problems would be quickly settled, and that in the meantime, he would be treated very well. However, many of his personal assets in Arabistan were quickly liquidated and his properties eventually came under the domain of the Imperial government after Reza Khan was crowned the new Shah. The emirate was abolished and the provincial authority took full control of regional affairs.

Khaz'al spent the rest of his life under virtual house arrest, unable to travel beyond Tehran's city limits. He was able to retain ownership of his properties in Kuwait and Iraq, where he was exempted from taxation. In May 1936, while alone in his house, as earlier in the day his servants had been taken to court by the police, he was murdered by one of the guards stationed outside his house under direct orders from Reza Shah.

Freemasonry

Sheikh Khaz'al was an active Freemason and a recipient of many high Masonic honours. Up until his death, Sheikh Khaz'al was the most influential of all Masons of the Middle East.[13] It is not clear when exactly Sheikh Khaz'al joined Freemasonry. What is known, is that he was the first Freemason among the inhabitants of the Persian Gulf, and that he became the Grand Master of Freemasonry in all Mesopotamia. It is likely that the East India Co. established the first Masonic lodge in the area and that Sheikh Khaz'al became its first chairman.

A secret document found after the seizure of Masonic lodges in Egypt was the agenda for al-Abbasi Lodge No. 223 of Cairo for its meeting of 16 December 1923. One of the items discussed the subject of presenting Sheikh Khaz'al, the chairman of 'Khaz'al' lodge, and the regional Grand Master of Mesopotamia, with a decoration in recognition of his valuable services to Freemasonry.[14]

" The bestowal of honours to all of the Brothers mentioned, in recognition of their great services:

Firstly - His Greatness, the Sardar Aqdas, Ruler of Arabistan and Prince of Nuyan, respected Brother, Khaz'al Khan Sultan of Mohammerah, and Chairman of the Khaz'al Khan Lodge and Provincial Grand Master of Mesopotamia..."

Humanitarian acts

Chaldean victims of the Ottoman Empire

In October 1914, the Assyrian genocide occurred whereby thousands of Chaldeans were killed or deported by the Ottoman Empire. After having experienced such atrocities on the hands of the Ottomans, the Chaldean Catholics began to migrate away from their homeland, in search of somewhere safer. Some of these emigrants found their way to the city of Ahwaz where,

"...under the protective shadow of His Highness the Sardar Aqdas… they found refugee, and when their numbers increased, they approached His Highness asking for a plot of land that they may build a church and a school to bring up their children and he accepted with what he promised of the welcoming of the heart and the tolerance of the palm and he granted them the land and he provided them endowment. The Chaldeans had found in Ahwaz justice and safety and were envied by their brothers who had not emigrated." [15]

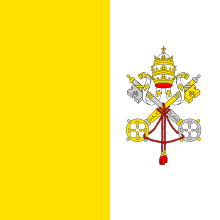

When the Patriarch of Babylon for the Chaldean Catholics, Emmanuel Joseph saw what had been done, in the year 1920, he decided to repeat what he had seen to Pope Benedict XV. He explained that those of his spiritual children who had remained happy in the East were the ones who emigrated to Ahwaz and lived under the shadow of the Sardar Aqdas. The Pope was moved by the benevolence of Sheikh Khaz’al Khan towards those who were distressed amongst the children of the church and he granted him the Order of St Gregory the Great of the rank of Knight Commander, announcing his thanks and his acknowledgment of "...the grace of this great and generous Arab King".[15]

King Faisal I attempts to kidnap Sheikh Khaz’al from Tehran

The first of a number of attempts to rescue Khaz’al was in 1927 by King Faisal I of Iraq. Faisal felt that the arrest of Khaz’al and the injustice of the Persian government towards Arabistan were severe and cruel. Moreover, Faisal felt that he was in debt to Khaz’al for withdrawing his candidacy for the throne of Iraq. For Faisal, after being deposed from the Kingship of Syria, was a King without a country. He viewed this mission not only as an act of loyalty, but more importantly, of duty. Faisal informed Nuri al-Said of his plan to which the latter recommended using diplomacy rather than physical intervention.[16]

Meanwhile, al-Said, without Faisal's knowledge, informed Henry Dobbs, the British Ambassador to Iraq, of the latters intentions of kidnapping Khaz’al. Dobbs immediately met with Faisal and warned him of the consequences of such an act, stating that ‘His Majesty's Government’ would take a firm stand against him. "Do not play with fire, King Faisal," warned Dobbs.[16]

Khaz'al in literature

Abd al-Masīh al-Antākī in The Kitāb Riyāḍ Al-Khazʻalīyah Fī al-Siyāsah Al-Insānīyah (The Garden of Khaz’al in Human Politics).

The official author of the book is Khaz’al, but it was written by the Syrian poet and journalist, Abdul Maseeh al Antaki. Born in Aleppo, with Greek origins, he emigrated to Egypt and travelled the Arab world. He established the Al Omran newspaper in Egypt and became a frequent figure in Khaz’al's court.

He explains, in the introduction of the book, his objective:

“...and here I am mentioning His Highness the Sardar Aqdas, so that the reader my learn that His Highness the author is the bearer of the sword and the pen, and that amongst the Arab Kings and Princes he is the greatest King, the most magnificent Prince, the respectable gentleman, the most knowledgeable of the knowledgeable, and I am full of what I have seen myself and have known after my long mission and my study, unexaggerated in my story, and not passed the line of rationality and guidance, so that the Arabs may know that His Highness the Sovereign the Mu’iz has combined between determination and knowledge, and has been struck by both by the most blessed arrow, that is how that Kings and Princes should be, if they sought to revive the glory of their forefathers.” [15]

Ameen Rihani in Molouk el-Arab (Kings of the Arabs)

"Mention one who does not know him. For he is amongst the Arab Princes. His Emirate being within the vicinity of the Persian Empire. He is the eldest, after King Hussein, the first to fame, and the greatest in generosity. This is what is known by most of those who know in the Arab countries. What most people outside of Kuwait and Basrah do not know, is that this Arab Prince is of the status of the Princes of the Abbasid era for he is rich, wise and generous together. He is like the Barmakids in his generosity, his taste, and his literature. He loves music, literature and poetry and leans towards all that provides pleasure and joy, be it mental, social or physical. Yes, the Sheikh Khaz'al has a universal humanitarian taste, for he does not alienate that which is ugly or vilified in life, and he knows no preference or discrimination in his generosity. A singer visits from Aleppo or Damascus to Mohammerah with nothing but her anklets. After residing a few months at the palace, she returns rich and laden with jewels. And the poets come with poems of praise in their pockets, and return from Mohammerah with bags of gold. He is not in need of my testimony for if he were to wear his official gown, he carries on his chest the testimonies of the Kings of the Earth, of which is the Papal Order of Saint Gregory the Great. Amongst those honours are two which are not seen by all, yet are only seen by those who look at this man with the eye of poetry and philosophy. For in his human capacity, he holds decorations from the philosopher Epicurus and the wise divine mystic Ibn Arabi."

Views

In regard to religious extremism, Khaz'al said:

It is the scourge of the world. And if I had to come back after death to this Earth, I would only do so if there was no longer a trace of religious extremism left. All humans are brothers whether they like it or not.[17]

Honours

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Places named after Sheikh Khaz'al

- Khazaliyeh, a village in present day Iran, once part of the Emirate of Mohammerah

- Al-Khazaliya Street Doha, Qatar

- Qasr Khaz'al (the Khaz'al Palace), Kuwait

- Diwan Khaz'al, Dasman, Kuwait [19]

Publications

- Al-Riyāḍ al-Khazʻalīyah fī al-siyāsah al-insānīyah (Arabic: الرياض الخزعلية في السياسة الإنسانية)

See also

- al-Sabah

- Ethnic politics of Khuzestan

- History of Khuzestan

References

- "Sardar Aghdas". Dehkhoda Dictionary. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- "'File 53/75 (D 156) Shaikh Khazal's Claim against Kuwaiti Merchants' [13r] (34/140)". British Archives. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Allday, Louis (7 November 2017). "The Shaikh who lost his Shaikhdom, Khaz'al al-Ka'bī of Mohammerah".

- MILANI, MOHSEN M. "IRAQ vi. PAHLAVI PERIOD, 1921-79". Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Shahnavaz, Shahbaz. "ḴAZʿAL KHAN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Ghani, Cyrus (1998). Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power. p. 203.

- Navabi, Hesamedin (2010). "D'Arcy's Oil Concession of 1901: Oil Independence, Foreign Influence and Characters Involved". Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. 33.

- Vassiliou, M.S (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. pp. 285.

- Khalif, Hussein. Tareekh Al Kuwait Al Siyasi. p. 221.

- Katouzian, Homa (2006). State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis. I.B.Tauris.

- British Relations with Khazal, Sheikh of Mohammerah. India Office Records and Private Papers.

- Wynn, Antony (2013). Days of God: The Revolution in Iran and its Consequences".

- Rich, Paul John (2009). Creating the Arabian Gulf: The British Raj and the Invasions of the Gulf. United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Safwat, Najdat Fathi (1980). Arab Papers; Freemasonry in the Arab World. London: An Arab Research Centre Publication.

- Khan, Khaz’al (1911). Riyāḍ Al-Khazʻalīyah Fī al-Siyāsah Al-Insānīyah. p. 9.

- Ahmad, Nassar. Al Ahwaz, The Past, The Present, The Future. Dar Al Sharq Al Awsat.

- al-Rayhani, Amin (1924–1925). Muluk al-Arab, aw Rihlah fi al-bilad al-Arabiah. pp. Vol 2, part 6 on Kuwait.

- Khan, Khaz’al (1911). Riyāḍ Al-Khazʻalīyah Fī al-Siyāsah Al-Insānīyah. p. 9.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sheikh Abdullah Al-Jabir Palace". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

External sources

- Tarikh-e Pahnsad Saal-e Khuzestan (Five Hundred Year History of Khuzestan) by Ahmad Kasravi

- Jang-e Iran va Britannia dar Mohammerah (The Iran-British War in Mohammerah) by Ahmad Kasravi

- Tarikh-e Bist Saal-e Iran (Twenty Year History of Iran) by Hossein Maki (Tehran, 1945–47)

- Hayat-e Yahya (The Life of Yahya) by Yahya Dolatabadi (Tehran, 1948–52)

- Tarikh-e Ejtemai va Edari Doreieh Qajarieh (The Administrative and Social History of the Qajar Era) by Abdollah Mostofi (Tehran, 1945–49) ISBN 1-56859-041-5 (for the English translation)

- Amin al-Rayhani, Muluk al-Arab, aw Rihlah fi al-bilad al-Arabiah (in two volumes, 1924–25), Vol 2, part 6 on Kuwait.

- Ansari, Mostafa -- The History of Khuzistan, 1878-1925, unpublished PhD. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1974

External links

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Khaz’al Khan Ibn Haji Jabir Khan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||