Keszthely culture

Keszthely culture was created ca. 500 – 700 by the Romanized residents of Pannonia who lived in the area of the fortified village of Castellum (now Keszthely), near Lake Balaton in now western Hungary.

This culture flourished under the Avars' domination of Pannonia and is especially noteworthy for artifacts (mainly of gold) produced by artisans in Keszthely.

History

_-_Byzantine(-style)_girl's_jewellery%2C_Hungary_-_garment_pin.jpg)

At Fenekpuszta [Keszthely] . . . excavations have brought to light a unique group of finds that suggest not only Christians but Romans too. . . . There are finds such as a gold pin with the name BONOSA proving that some ethnic group of Roman complexion remained at Fenekpuszta [after the barbarian invasions][1]

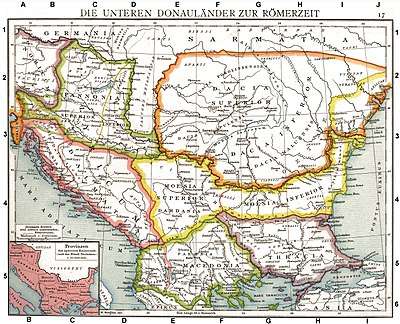

Pannonia, a province of the Western Roman empire, was devastated by the barbarian invasions (Huns, Gepids, Avars, etc.). Only a few thousand Romanized Pannonians survived the onslaughts, mainly around Lake Pelso (now lake Balaton) in small fortified villages such as Keszthely.

The Romanic population from Pannonia created the Keszthely culture that evolved mainly during the 6th-7th centuries. Its artifacts were made in the workshops of Roman origin located mainly in the fortified settlements of Keszthely-Fenékpuszta and Sopianae (modern Pécs). The Romanic craftsmen worked for their Gepid and Avar masters.

Under the Avars, the Roman castle of Fenékpuszta near Keszthely and the surroundings were not occupied, so the original Romanized inhabitants lived on undisturbed. They paid food and artisan goods for peace from the Avars. After 568 new Christian Romanized Pannonians arrived here, probably from the destroyed Aquincum (modern Budapest). The Keszthely-Fenékpuszta fortress became the centre of a 30 km diameter area, where the people buried their dead adorned with jewellery and clothing of Byzantine origin. They rebuilt the fortress basilica, where the principals of the community were buried, while their relatives found their final resting places next to the nearby horreum (granary). In 626, the Avars were seriously defeated under Constantinople, which was followed by a civil war. The leaders of the Keszthely-Fenékpuszta community had supported those who were later defeated. That was why the Avars besieged and then destroyed the fortress of Fenékpuszta. They made the rest of the Romanized population move into the territory of the town centre. The Christian Romanized population was subjected to military suppression. The cemeteries of the 7th and 8th centuries entombed both Avars and Christians, but they were buried separately. The different religions did not allow them to mix even after death. The Christian Romanized populace, which spoke its own Romance Pannonian language, was cut from the outer world and created a unique, characteristic material culture, which we know from the artifacts of the cemeteries near Keszthely. These finds have been termed Keszthely culture. At that time, Keszthely was the center of the Pannonian region, because the area of Lake Balaton was crossed by roads connecting the Danube and the Mediterranean.

At the end of the 8th century, the Franks under Charlemagne overthrew the Avar Empire and invaded the Pannonian plains. The Christian Romanized populace living around Keszthely quickly adopted the customs of western Christendom, which meant among other things that they buried their dead without grave goods so now it is impossible to identify them. The Fenékpuszta fortress was repaired again in the 9th century. Its walls accommodated and gave shelter to the descendants of the Avars and the Slavic people who had migrated in at the beginning of the century. Their cemeteries maintained many of the pagan customs. The 10th century was the darkest period of Keszthely's history. No traces of any surviving Romanized Pannonian populace of the earlier period nor of the conquering Hungarians are known to us.

Handicrafts

By the end of the 6th century, the Romanized populace was mainly buried in the row cemeteries that were newly laid out in the area of the late Roman fortresses of Keszthely (Castellum) and Pécs (Sopianae) (southwestern Hungary). During the period of Avar rule, Romanized and Byzantine people arrived from the Balkans, and they helped develop a community of skilled artisans. These communities, probably Christian, preserved or renewed their artistic relations with the Romanized population of the Mediterranean.

The characteristic garb of women included earrings with basket-shaped pendants, disc brooches with early Christian motifs, and garment pins. The early Christian symbols include crosses, bird-shaped brooches and pins decorated with bird figures (one bird-shaped brooch bears an incised cross). The Romanized populace of Pannonia in general became ‘Avarized’, and their ‘island’ of late antique culture is documented only in the immediate vicinity of Keszthely, where their traditional costume was worn until the beginning of the 9th century.

Language

The name Keszthely (IPA [ˈkɛst.hɛj]) could be related to the Istriot–Venetian castei, which means "castle", and is probably an original word of the Pannonian Romance language, according to the Austrian linguist Julius Pokorny.[2] He also posits that the word Pannonia is derived via Illyrian from a Proto-Indo-European root *pen- "swamp, water, wet". If true, that would suggest that the pre-Roman language of Pannonia was an Illyrian language.

According to Romanian linguist Alexandru Rossetti,[3] Pannonian Romance probably contributed to the creation of the 300 basic words of the "Latin substratum" of the Balkan Romance languages.

Some scholars argue that the Pannonian Romance lacks clear evidences of existence, because no written sources exist. However, according to Árthur Sós,[4] in some of the 6000 tombs of the Keszthely culture, there are words in vernacular Latin. This is the case, for example, of a gold pin with the inscription BONOSA.[5]

See also

References

- Mócsy, András. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire p. 353

- Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- Istoria limbii române

- Cemeteries of the Early Middle Ages (6th–9th centuries) at Pókaszepetkin

- Mócsy, András. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: a history of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman Empire p.353

Further reading

- Magdearu, Alexandru. Românii în opera Notarului Anonym. Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Bibliotheca Rerum Transsylvaniae, XXVII. Cluj-Napoca 2001.

- Mócsy, András. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. London, 1974 ISBN 0-7100-7714-9

- Mommsen, Theodor. The Provinces of the Roman Empire. Barnes & Noble. New York, 2003

- Remondon, Roger. La crise de l’Empire romain. Collection Nouvelle Clio – l’histoire et ses problèmes. Paris 1970

- Szemerényi, Oswald. Studies in the Kinship Terminology of the Indo-European Languages. Leiden 1977

- Tagliavini, Carlo. Le origini delle lingue neolatine. Patron Ed. Bologna 1982

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keszthely culture. |