Kenzō Takada

Kenzō Takada (高田 賢三, Takada Kenzō) is a Japanese-French fashion designer. He is also the founder of Kenzo, a worldwide brand of perfumes, skincare products and clothes, and is the acting Honorary President of the Asian Couture Federation.

Kenzō Takada | |

|---|---|

たかだ けんぞう 高田 賢三 | |

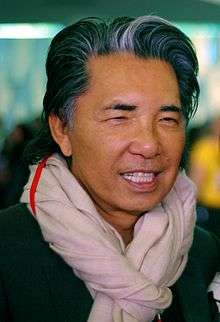

Takada in June 2008 | |

| Born | February 27, 1939 Himeji, Hyōgo, Japan |

| Nationality | French Japanese (expatriate) |

| Alma mater | Bunka Fashion College |

| Occupation | Fashion designer, film director |

| Known for | Founder of Kenzo |

| Partner(s) | Xavier de Castella |

| Awards | Ordre des Arts et des Lettres |

Early life

Takada was born on February 27, 1939 in Himeji, Hyōgo Prefecture, to parents who ran a hotel.[1] His love for fashion developed at an early age, particularly through reading his sisters' magazines.[2] He briefly attended Kobe City University of Foreign Studies, but after his father died during Takada's first year at university,[3] he withdrew from the program against his family's wishes.[2] In 1958, he enrolled at Tokyo's Bunka Fashion College, which had then just opened its doors to male students.[4] During his time at Bunka, Takada won a fashion design competition, the Soen Award, in 1961.[4][5]:122 At this time, Takada gained experience working in the Sanai department store,[2][6] where he designed up to 40 outfits a month as a girl's clothing designer.[7]

Takada was inspired by Paris, especially designer Yves Saint Laurent.[8] His interest in Paris was further fostered by his teacher at Bunka, Chie Koike, who was educated at L'École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne.[5]:113[9]:142 In preparation for the 1964 Summer Olympics, the government demolished Takada's apartment in 1964, providing him with some monetary compensation.[10] Under the advice of his mentor, and using his compensation money, Takada went on a month-long trip by boat to Paris, stopping along the way at various cities like Hong Kong, Ho Chi Minh City, Mumbai, and Marseille.[10][11] He ultimately arrived at the Gare de Lyon train station on January 1, 1965.[4] Takada's first impression of Paris was that it was "dismal and bleak", but began to warm up to the city when his taxi took him past the Notre Dame de Paris, which he described as "magnificent".[12]

Fashion career

Takada initially struggled in Paris, selling sketches of designs to fashion houses for 25 F each.[11] He had intended to leave Paris for Japan after a few months, but vowed not to do so until he had created something there, as he was determined to open a boutique fashion house in an area where his peers had not opened one.[4][13] During this time, Takada worked as a stylist at a textile manufacturer called Pisanti.[3][9]:142[14]

In 1970, while at a flea market, Takada met a woman who wanted to rent out a small space in the Galerie Vivienne to him for cheap.[1] Takada accepted the offer, and opened up shop as a designer. With very little money to work with, he mixed and matched $200 in fabrics from the Saint Pierre market in Montmartre, creating an eclectic and bold first fashion collection.[1] Takada presented the collection at his first fashion show at the Galerie Vivienne. With no money to afford professional fashion models for the event, Takada and his friends opted to paint the pimples of an acne-covered model green.[1][3]

Inspired by painter Henri Rousseau, and in particular The Dream, Takada painted the interior of his shop with a jungle-like floral aesthetic.[11][15] Wanting to combine the jungle aesthetic with his homeland, the designer decided to name his first store "Jungle Jap".[11] The store's name did not go without controversy: in 1971, the Japanese American Citizens League issued a summons to Takada while on his first visit to the United States, challenging him to remove the word "Jap" from his business's name.[16] However, the State supreme court upheld the ability to use the term as part of a trademark the following year.[17] Takada and his team opted to rename the brand once Takada returned to France.[15]

Takada's efforts paid off quickly – in June 1970, Elle featured one of his designs on its cover.[5]:117 He moved locations from the Galerie Vivienne to the Passage Choiseul in 1970.[16] Takada's collection was presented in New York City and Tokyo in 1971. The next year, he won the Fashion Editor Club of Japan's prize.[18] In October 1976, Takada opened his flagship store, Kenzo, in the Place des Victoires.[19][20] Takada proved his sense of dramatic appearance when, in 1978 and 1979, he held his shows in a circus tent, finishing with horsewomen performers wearing transparent uniforms and he himself riding an elephant.[21][22] Takada even had the chance to direct a film called Yume, yume no ato, which was released in 1981.[23][24]

Takada's first men's collection was launched in 1983.[2] In August 1984, The Limited Stores announced that they had signed Takada to design a less-expensive clothing line called Album by Kenzo.[25] A children's line called Kenzo Jungle, as well as men's and women's jeans, was released in 1986.[19]

Takada had also made ventures into the perfume business. He first experimented with perfumes by releasing King Kong in 1980, which he created "just for fun".[26][27] In 1988, his women's perfume line began with Kenzo de Kenzo (now known as Ça Sent Beau), Parfum d'été, Le monde est beau and L'eau par Kenzo. Kenzo pour Homme was his first men's perfume (1991). FlowerbyKenzo, launched in 2000, was listed by Vogue's website as one of the best classic French perfumes of all time.[28] In 2001, a skincare line, KenzoKI was also launched.[29][30]

Since 1993 the brand Kenzo is owned by the French luxury goods company LVMH. In 2016, he designed a perfume for Avon.

Retirement from the fashion industry

Takada announced his retirement in 1999 to pursue a career in art,[2] leaving Roy Krejberg and Gilles Rosier to handle the design of Kenzo's men's and women's clothing, respectively.[31][32] However, in 2005 he reappeared as a decoration designer presenting Gokan Kobo (五感工房 "workshop of the five senses"), a brand of tableware, home objects and furniture. After a few years off, he wanted to take a new direction, stating "when I stopped working five years ago, I went on vacation, I rested, I traveled. And when I decided to work again, I told myself it would be in decoration, more than fashion."[33] Additionally, in 2013 Kenzo joined the Asian Couture Federation as the organisation's inaugural Honorary President.[34]

Takada was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour on June 2, 2016.[20][35] He was further honored by a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 55th Fashion Editors' Club of Japan Awards in 2017.[18] That same year, Takada unveiled a new collection with Roche Bobois, giving its Mah Jong sofa new upholstery and creating a line of ceramics.[36][37] Since his departure from the fashion industry, Takada has occasionally ventured back into fashion. He designed costumes for the production of Madama Butterfly by the Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation during 2019.[38] He also used his eye for design in other ways, collaborating with the Mandarin Oriental Jumeira in Dubai to design the hotel's first publicly-displayed Christmas tree during the 2019 holiday season.[39]

In January 2020, Takada announced that he would be launching a new lifestyle brand named K3.[40] The brand made its first appearance on 17 January 2020 at the Maison et Objet trade show, as well as in a Parisian showroom.[41]

Personal life

Takada was in a relationship with Xavier de Castella, who died in 1990 from AIDS.[42][43][44] De Castella helped design Takada's 14,000-sq-ft Japanese-style house, which started construction in 1987 and was completed in 1993.[45][46]

References

- Dorsey, Hebe (14 November 1976). "Fashion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Woolnough, Damien (1 February 2013). "Brand watch: Kenzo Takada". The Australian. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- McDonald, Marci (8 August 1977). "All the rage in Paris". Maclean's. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Lim, Leslie Kay (24 February 2014). "Quintessentially Asian: Fashion designers Kenzo Takada, Junko Koshino". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2004). The Japanese revolution in Paris fashion. Oxford [England]: Berg. ISBN 9781417598021. OCLC 60562175.

- Dirix, Emmanuelle (2016). Dressing the Decades: Twentieth-century Vintage Style. Yale University Press. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-300-21552-6.

- Sowray, Bibby (2012-03-12). "Kenzo Takada". British Vogue. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Gaignault, Fabrice (28 February 2019). "La jeunesse éternelle de Kenzo Takada". Marie Claire (in French). Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Polan, Brenda (2009). The great fashion designers. Tredre, Roger. (English ed.). Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN 9780857851741. OCLC 721907453.

- La Torre, Vincenzo (14 March 2019). "Fashion legend Kenzo Takada's amazing life revealed in new book". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Cook, Grace (31 January 2019). "Kenzo Takada — the journey from 'Jungle Jap' to Kenzo". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "Book on Kenzo traces how he 'dressed up' Paris with colour, flowing lines". The Straits Times. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Vicente, Álex (28 October 2018). "Kenzo: "Lamento haber vendido mi marca. Fue un largo luto que ahora llevo mejor" | Moda". S Moda EL PAÍS (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "KENZO". Encyclopædia Universalis (in French). Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- Breeze, Amanda (8 February 2019). "interview | kenzo takada". Schön! Magazine. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Morris, Bernadine (12 July 1972). "Designer Does What He Likes—And It's Liked". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "Court Here Upholds 'Jap' as Trademark". The New York Times. 29 June 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Wetherille, Kelly (31 March 2017). "Kenzo Takada Receives Lifetime Achievement Award". WWD. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Herold, Stephanie Edith (2015). "Kenzo Takada". Fashion Photography Archive. Bloomsbury. doi:10.5040/9781474260428-fpa102. ISBN 9781474260428.

- Guilbault, Laure (3 June 2016). "France Honors Kenzo Takada". WWD. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Kenzo: star of the east". The Independent. 4 December 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Nelson, Karin (1 August 2012). "In Living Color". W Magazine. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Yume, Yume No Ato (1981)". BFI. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Yoshiharu Tezuka (1 November 2011). Japanese Cinema Goes Global: Filmworkers' Journeys. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-988-8083-32-9.

- "Kenzo to Do Inexpensive Line". The New York Times. 14 August 1984. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Hyde, Nina S. (15 April 1979). "Fashion Notes". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Bauck, Whitney (29 June 2017). "Kenzo Takada on His Very Creative Life Before, During and After Founding Kenzo". Fashionista. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Piercy, Catherine. "The Best Classic French Perfumes of All Time". Vogue. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Douglas, Joanna (5 October 2015). "Kenzo's Skin Care Line Hits the States; Worth the Wait". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Petit, Elodie (8 August 2008). "Kenzo Parfums souffle ses 20 bougies ! - Elle". elle.fr (in French). Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Quintanilla, Michael (1999-10-08). "Kenzo Bids Fashion Adieu". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Menkes, Suzy (1999-09-14). "Gilles Rosier: On to Kenzo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Paris-based designer Kenzo Tanaka back in the spotlight". sawfnews.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- Hong, Xinying (15 October 2013). "Kenzo Takada: Asian fashion designers can become the next trendsetters". Her World Plus. Her World. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Sciola, Giulia (21 November 2018). "Chi è Kenzo Takada, tigre gentile della moda". Esquire (in Italian). Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Luckel, Madeleine (2017-06-30). "Legendary Designer Kenzo Takada Unveils a New Line for Home". Vogue. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- Eckardt, Stephanie (2017-06-29). "Catching Up with Kenzo Takada, the OG Founder of Kenzo Who Is Designing Under His Own Name Again at 78". W Magazine | Women's Fashion & Celebrity News. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- Lee, Jae (2019-09-29). "Kenzo Takada adds to a legacy of operatic style". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Shaikh, Ayesha Sohail Shehmir (2019-11-26). "This Fashion Icon Will Design Mandarin Oriental Jumeira, Dubai's First Christmas Tree". Harper's BAZAAR Arabia. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Nedbaeva, Olga (2020-01-23). "Kenzo dreams up another design classic". Asia Times. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Burlet, Fleur (2020-01-10). "Kenzo Takada Unveils Lifestyle Brand". WWD. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- "Kenzo Takada: "Farben trage ich nur im Urlaub" - derStandard.at". Der Standard (in German). 18 November 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Rire à capri, mourir à venise". L'Humanité (in French). 27 October 1990. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Boulay, Anne (9 December 1999). "Kenzo Takada, 60 ans, quitte le monde de la mode et ses fleurs pour se concocter une existence sans soucis. Au Japonais absent". Libération.fr (in French). Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Rafferty, Jean (14 December 2007). "The house Kenzo built". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Zahid Sardar (16 October 2014). In & Out of Paris: Gardens of Secret Delights. Gibbs Smith. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-1-4236-3271-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kenzo Takada. |