Keaoua Kekuaokalani

Keaoua Kekua-o-kalani (sometimes known as Kaiwi-kuamoʻo Kekua-o-kalani) was a nephew of the king Kamehameha I, the chief from Hawaii Island who unified the Hawaiian islands.

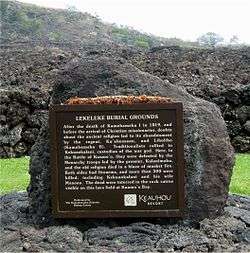

| Keaoua Kekua-o-kalani | |

|---|---|

Memorial at Kuamoʻo | |

| Died | December 1819 Kuamoʻo |

| Spouse | Manono II (probably others) |

| Father | Keliʻimaikaʻi |

| Mother | Kiʻilaweau |

Family

He was the son of Kamehameha's younger brother Keliʻimaikaʻi and Kamehameha's half-sister Kiʻilaweau. After Kamehameha died in 1819, Keaoua rebelled against Kamehameha's successor, his son Kamehameha II. Keaoua's rebellion was brief; he was killed in battle about 21 December 1819.

ʻAi Noa

After Kamehameha died, power was officially assumed by Kamehameha's son Liholiho. Liholiho, at the urging of powerful female chiefs such as Kaʻahumanu, abolished the kapu system that had governed life in Hawaiʻi for centuries. Henceforth, men and women could eat together, women could eat formerly forbidden foods, and official worship at the stone platform temples, or heiaus, was discontinued. This event is called the ʻAi Noa, or free eating.

historian Gavan Daws suggests that as [1] this was a decision taken by the chiefs, and it primarily affected the state religion, commoners could still worship their family protective deities (aumakua); hula teachers could make offerings to Laka and Hawaii islanders could make offerings to the goddess Pele. Nonetheless, Liholiho ordered the destruction of all Heiau temples throughout the islands, and as asserted by Kalakaua[2], Liholiho's edicts were seen as a total repudiation of the native Hawaiian religion.

Rebellion

Some chiefs felt that if they were to abandon the kapus and the services at the heiaus, they would lose the religious justification and support for their rule. Liholiho, they felt, was courting disaster, and must be opposed, lest he take down everyone with him. However, it is likely that there was also genuine loyalty at play, to the cultural norms, and religious beliefs the rebels had been raised in.

If Liholiho were to die or be overthrown, Keaoua would have a good claim to the throne. He was outraged by the abandonment of the sacred traditions and withdrew from the royal court. He staying at Kailua-Kona, on Hawaii Island, and retired to Kaʻawaloa at Kealakekua Bay. Many ʻAi Noa opponents joined him and urged him to try for the throne, saying, "The chief who prays to the god, he is the chief who will hold the rule."[3] Some of the Hawaiians living in Hamakua, on the north coast, rebelled outright and killed some soldiers sent against them. Keaoua had, according to Kalakaua, been trained as a priest by Hewahewa, the apostate high priest who had joined Liholiho in repudiating the native religion. Consequently, Keaoua took on the mantle of high-priest, and undertook to defend the old religion by force.

Emissaries

Liholiho and his chiefs took counsel and decided to send emissaries to Keaoua, asking him to abandon his defiance, return to Kailua, and rejoin the free eating. Keaoua received the emissaries with apparent deference and said he was ready to return to Kailua the next day, but would not join in the free eating. The emissaries retired to rest, thinking the problem solved.

According to Kamakau, Keaoua's supporters spent the night arguing with their leader, urging him to kill the emissaries and mount a decisive rebellion. Keaoua forbade any assassinations but the next morning, when he and his followers were to board canoes for the return to Kailua, he refused. He said he and his men (drawn up in ranks, in warrior regalia) would go by land.

Battle

This was tantamount to war. Liholiho sent forces under Kalanimoku to intercept Keaoua. Their forces met at Kuamoʻo, just South of Keauhou Bay. Keaoua was eventually killed by rifle fire. His wife Manono, sister of Kalanimoku and former wife of Kamehameha I, who had been fighting at her husband's side, begged for mercy but was shot down as well. The rest of Keaoua's army scattered and Liholiho's victory was complete.

This was the only armed rebellion in favor of the native Hawaiian religion.

Legacy

Keaoua Kekua-o-kalani was the last partially recognized high priest, and the last defender of the native Hawaiian religion, until modern times when various revivals have occurred. The gymnasium at Old Kona Airport State Recreation Area is named in his honor.

References

- Daws, 1967, pp. 54–59

- Kalakaua, 1888, pp. 431-446

- Kamakau, 1961, p. 226

- Daws, Gavan (1968). Shoal of Time.

- Kamakau, Samuel Manaiakalani (1992). Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii. Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 9780873360142. (a collection of newspaper articles written by Kamakau, in Hawaiian, during the 1800s)

- Hawaii), David Kalakaua (King of (1888). The Legends and Myths of Hawaii: The Fables and Folk-lore of a Strange People. C.L. Webster.

- M, HIRAM BINGHAM, A. (1848). RESIDENCE OF TWENTY-ONE YEARS IN THE SANDWICH ISLANDS:.