Keʻelikōlani

Ruth Ke‘elikōlani Keanolani Kanāhoahoa (February 9, 1826[7] – May 24, 1883), was a member of the Kamehameha family, the founding dynasty of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. She served as Royal Governor of the Island of Hawaiʻi. As primary heir to the Kamehameha family, Ruth became a landholder of what would become the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate funding the Kamehameha Schools. Unlike most of the rest of the royal family, Keʻelikōlani retained traditional Hawaiian cultural practices. Her name Keʻelikōlani means leaf bud of heaven.[8]:303

| Keʻelikōlani | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Her Royal Highness[4][5][6] | |||||

| |||||

| Born | February 9, 1826 Honolulu, Oʻahu, Kingdom of Hawaiʻi | ||||

| Died | May 24, 1883 (aged 56) Kailua-Kona, Hawaiʻi, Kingdom of Hawaiʻi | ||||

| Burial | June 17, 1883 Mauna ʻAla Royal Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | William Pitt Leleiohoku I Isaac Young Davis | ||||

| Issue | John William Pitt Kīnaʻu Keolaokalani Davis William Pitt Leleiohoku II (hānai) | ||||

| |||||

| House | Kamehameha | ||||

| Father | Kahalaiʻa Luanuʻu or Mataio Kekūanāoʻa | ||||

| Mother | Kalani Pauahi | ||||

Family

Keʻelikolani's mother was High Chiefess Kalani Pauahi (1804–1826), daughter of High Chief Pauli Kaʻōleiokū and his first wife High Chiefess Keoua-wahine.[9] Her mother died giving birth to her on February 9, 1826, after her mother had married on November 28, 1825 to the man believed to be her father, Mataio Kekūanāoʻa (1793–1868). She was considered to have two fathers, called a poʻolua ancestry (meaning roughly "two heads of the family"). High Chief Kahalaiʻa Luanuʻu (died 1826), Governor of Kauaʻi island also claimed her as his daughter. Kahalaiʻa was a nephew of King Kamehameha I, the son of the king's half-brother Kalaʻimamahu and High Chiefess Kahakuhaʻakoi Wahinepio from Maui.[10] Keʻelikolani's traditional but now unorthodox birth was one reason she was regarded outside the legitimate birth of Christian Hawaiian nobility. King Kamehameha III established in the Constitution of 1840 that eligibility to be monarch required a Christian-style legitimate birth. Ruth was adopted and raised by Kamehameha's most powerful queen, Kaʻahumanu, who acted as regent under kings Kamehameha II and III.

Although her paternity was questionable, Mataio Kekūanāoʻa claimed her as his own natural child. He took her into his household after Kaʻahumanu's death and included her in his will and inheritance. This made her the half-sister of King Kamehameha IV and King Kamehameha V and Princess Victoria Kamāmalu.[11]:8–13

Marriages

Before the age of sixteen, she married her first husband William Pitt Leleiohoku I (1821–1848), Governor of Hawaiʻi, former husband of Princes Nāhiʻenaʻena, and son of High Chief William Pitt Kalanimoku the Prime Minister of Kamehameha I. Soon after she married Leleiohoku, her 27-year-old husband died in a measles epidemic.[11]:19

On June 2, 1856, she married her second husband, Isaac Young Davis (c. 1826–1882), son of George Hueu Davis and his wife Kahaʻanapilo Papa (therefore grandson of Isaac Davis).[12] Standing at 6 ft 2 in, he was considered rather handsome by many including foreign visitors such as Lady Franklin and her niece Sophia Cracroft.[13] Their marriage was an unhappy one, and they divorced in 1868. The early loss of their son did not help.[11]:24

Children

She bore two sons, who both died young. John William Pitt Kīnaʻu, son of Leleiohoku, was born on December 21, 1842. He was taken away at an early age to attend the Royal School in Honolulu, and died September 9, 1859. Keolaokalani Davis, son of Isaac Young Davis was born in February 1862 and hānai (adopted) against his father's wishes to Bernice Pauahi Bishop. He died on August 29, 1863, aged one year and 6 months.[11]:34[14]:105

Her adopted son, called Leleiohoku II after her first husband, was born January 10, 1854, became Crown Prince of Hawaii, but died April 9, 1877, when only 23 years old. On the death of her adopted son, she demanded that Kalākaua and his family relinquish all rights to the estates she had bequeathed their brother, and that they be returned to her by deed. Her relations with King Kalākaua were distant, although she had close friendships with his sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani, and their mother, Keohokalole.[15]

She was godmother to Princess Kaʻiulani. At Kaʻiulani's baptism, Ruth gifted 10 acres (40,000 m2) of her land in Waikīkī where Kaʻiulani's father Archibald Cleghorn built the ʻĀinahau Estate. Kaʻiulani gave Ruth the pen name of Mama Nui meaning "great mother". Ruth insisted that the princess be raised to one day be fit to sit on the Hawaiian throne. Ruth's death in 1883 was the first of many deaths that Kaʻiulani would witness in her short life.

Defender of tradition

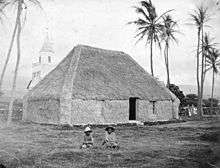

Ruth was a staunch defender of ancient Hawaiian traditions and customs. While the kingdom became Christianized, Anglicized, and urbanized, she preferred to live as a noble woman of antiquity. While her royal estates were filled with elegant palaces and mansions built for her family, she chose to live in a large traditional stone-raised grass house. While she understood English and spoke it well, she used the Hawaiian language exclusively, requiring English-speakers to use a translator. Although trained in the Christian religion and given a Christian name, she honored practices considered pagan, such as patronage of chanters and hula dancers.[15]

She continued to worship the traditional gods and various aumakua, or ancestral spirits. When Mauna Loa erupted in 1880, threatening the city of Hilo with a lava flow, her intercession with the goddess Pele was credited by Hawaiians with saving the city. When the ruling monarchs asked her to pose for official photographs, she often refused. Only a dozen photographs of Ruth are known to exist.

Appearance

Considered a beauty in her youth, she gained weight as she grew older, and a surgery for nasal infection disfigured her nose, although rumors circulated that it was her second husband Davis who had broken her nose in one of their many fights.[11]:5[16] She came to adopt some modern ways, such as Victorian fashions in hairstyle and dresses. Christian missionaries caused Hawaiian royal women to become self-conscious about their Hawaiian looks. They were uncomfortable with their dark skin and large bodies which had been considered signs of nobility for centuries. No matter how Westernized their manners, they were seen as a "Hawaiian squaw." By the last half of the 19th century, Hawaiian women were going in two different directions. Many European men married Hawaiian women they found exotic, favoring those who were thin and had pale complexions.[17]

Ruth defied this ideal, weighing 440 pounds (200 kg) and standing over 6 feet (1.8 m) tall. Her broad features were accentuated by a nose flattened by surgery for an infection. To add on to her stature, listeners described Princess Ruth's voice as a "distant rumble of thunder." She rejected English and the Christian faith. The U.S. minister to Hawaiʻi Henry A. Peirce dismissed the princess as a "woman of no intelligence or ability." Many Westerners interpreted her clear defense of the traditional ways as backward and stupid.[17]

Government and business

As the Governor of Hawaiʻi Island and heir to vast estates, she had more political power and wealth than most women in other parts of the world. For example, American women could not even vote at the time. Ruth's assertiveness were characteristic of her ancestors. She hired businessmen such as Sam Parker and Rufus Anderson Lyman who were descended from Americans to help her adapt to the new rules for land ownership. Instead of selling the land, she offered long-term leases, which encouraged settlers to start successful family farms, and gave her a secure income.[18] She was a shrewd businesswoman. In a notorious case, she sold Claus Spreckels her claims to the Crown Lands for $10,000. The lands were worth $750,000, but she knew her claims to them were worthless, since it had been decided in previous court cases that the lands were only entitled to whoever held the office of monarch.

In 1847 she was appointed to the Privy Council of Kamehameha III, and served from 1855 through 1857 in the House of Nobles. January 15, 1855 she was appointed to be the Royal Governor of the Island of Hawaiʻi, where she served until March 2, 1874.[19] When her last half-brother Kamehameha V died in 1872 leaving no heir to the throne, her controversial family background prevented her from being a serious contender to be monarch herself. Although she was considered a member of the royal family, along with Queen Emma and the king's father. In 1874, King Lunalilo then died, and the legislature elected Kalākaua as king, the first to be not descended from Kamehameha I. Keʻelikōlani was not declared as a member of the royal family, merely as a high chiefess by the new king. The young William Pitt Leleiohoku was named Crown prince, and history might have been very different if he had lived past 1877 and became a wealthy king. Instead, the increased reliance of the royal family on the treasury and governmental pensions to fund their lavish expenses is generally considered one factor that led to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893.[20]

She died at Huliheʻe Palace, Kailua Kona, Hawaiʻi Island, at 9am in the morning, Thursday. May 24, 1883.[11]:75[21][22] Later sources claimed she died on May 15.[23][24][25] Her body was shipped back to Honolulu for a royal funeral, and she was buried in the Kamehameha Crypt of the Royal Mausoleum, Mauna ʻAla, in Nuʻuanu Valley, Oahu. Her will had only one major bequest: to her cousin Bernice Pauahi Bishop the elaborate mansion, Keōua Hale on Emma Street in Honolulu, as well as approximately 353,000 acres (1,430 km2) of Kamehameha lands.[26] This totaled nearly nine percent of the land in the Hawaiian Islands.

Legacy

During her life Ruth was considered the wealthiest woman in the islands,[27] owning a considerable amount of land inherited from Kamehameha V[28] and her first husband Leleiohoku I.[29] Her vast estate passed to her cousin Bernice Pauahi Bishop,[30] with much of these lands becoming the endowment for Kamehameha Schools. On these lands downtown Honolulu, Hickam Air Force Base, part of Honolulu International Airport, Moana Hotel, Princess Kaʻiulani Hotel, Royal Hawaiian Hotel, among others, were built.

A documentary film was made of her life in 2004. As a tribute to her traditionalism, a version of the film was produced in the Hawaiian language.[20][31] In March 2017, Hawaiʻi Magazine ranked her among a list of the most influential women in Hawaiian history.[32]

Honours

See also

- Huliheʻe Palace – Kailua-Kona home of Princess Ruth

- Keōua Hale – Palace of Princess Ruth (downtown Honolulu)

References

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1881). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1881". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1881. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 64. hdl:10524/23168.

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1882). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1882". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1882. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 77. hdl:10524/23169.

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1883). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1883". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1883. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 74. hdl:10524/657.

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1881). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1881". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1881. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 64. hdl:10524/23168.

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1882). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1882". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1882. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 77. hdl:10524/23169.

- Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1883). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1883". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1883. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 74. hdl:10524/657.

- Keʻelikōlani considered her Birthday to be on February 9, 1826 but scholars such as A. Spoehr have suggested it was actually June 17, 1826. Kristin Zambucka, The High Chiefess: Ruth Keelikolani (1992)

- Cracroft, Sophia; Franklin, Jane; Queen Emma (1958). Korn, Alfons L. (ed.). The Victorian visitors: an account of the Hawaiian Kingdom, 1861–1866, including the journal letters of Sophia Cracroft: extracts from the journals of Lady Franklin, and diaries and letters of Queen Emma of Hawaii. The University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-87022-421-8.

- Henry Soszynski. "HH Princess Ruth Keelikolani". web page on "Rootsweb". Archived from the original on 2008-12-21. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- Rubellite Kawena Johnson. "Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani Poʻolua Child" (PDF). Biography Hawaiʻi: Five Lives, A Series of Public Rememberences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- Kristin Zambucka (1977). The High Chiefess: Ruth Keelikolani. Mana Pub. Co.

- Dean Kekoʻolani. "Hawaiian Genealogy: George Hueu Davis Sr". Kekoʻolani Ohana (Family) Web Site. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- Sophia Cracroft; Lady Franklin; Queen Emma of Hawaii (1958). Alfons L. Korn (ed.). The Victorian visitors: an account of the Hawaiian Kingdom, 1861–1866, including the journal letters of Sophia Cracroft: extracts from the journals of Lady Franklin, and diaries and letters of Queen Emma of Hawaii. The University Press of Hawaii. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-87022-421-8.

- George Kanahele (2002) [1986]. Pauahi: the Kamehameha legacy. Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-005-2.

- Kalena Silva. "Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani Hawaiian Aliʻi" (PDF). Biography Hawaiʻi: Five Lives, A Series of Public Rememberences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- Rosaly M. C. Lopes; Rosaly Lopes (2005). The Volcano Adventure Guide. Cambridge University Press Books. pp. 86–88. ISBN 0-521-55453-5.

- Karina Kahananui Green (2002). "Colonialism's Daughters". In Paul R. Spickard; Joanne L. Rondilla; Debbie Hippolite Wright (eds.). Pacific Diaspora: Island Peoples in the United States and Across the Pacific. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 242–248. ISBN 0-8248-2619-1.

- United States Senate (1903). Hawaiian Investigation: Report of Subcommittee on Pacific Islands and Porto Rico on General Conditions in Hawaii. Government Printing Office. p. 367.

- "Keelikolani, Ruth Princess office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- John Berger (May 30, 2004). "Getting to know Ruth: The princess defied Western ways and paid for it by being ignored by historians until now". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- Peterson, Barbara Bennett (1984). "Keelikolani". Notable Women of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 324–327. ISBN 978-0-8248-0820-4. OCLC 11030010.

- "Death Of Her Highness Princess Ruth Keelikolani". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. May 28, 1883. p. 2.; "Death Of Her Highness Ruth Keelikolani, At Kailua, Hawaii The Hawaiian Gazette". Honolulu. May 30, 1883. p. 2.; "A Notable Hawaiian Death Saturday Press". Honolulu. June 2, 1883. p. 3.; "Death of Princess Ruth The Pacific Commercial Advertiser". Honolulu. June 2, 1883. p. 2.; "Princess Ruth Keelikolani..." Daily Globe. St. Paul, MN. July 11, 1883. p. 8.

- All about Hawaii: The Recognized Book of Authentic Information on Hawaii, Combined with Thrum's Hawaiian Annual and Standard Guide. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 1886. p. 1.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. OCLC 500374815.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Select Committee on Indian Affairs (1978). Inclusion of Native Hawaiians in Certain Indian Acts and Programs: Hearings Before the United State Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs, Ninety-fifth Congress, Second Session, on S. 857 ... S. 859 ... S. 860 ... February 13-15, 1978. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- "Will of Ruth Keelikolani". Kamehameha Schools Archives. Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- Arthur Grove Day (1 January 1984). History makers of Hawaii: a biographical dictionary. Mutual Publishing of Honolulu. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-935180-09-1.

- United States. Department of State (1893). Papers Relating to the Mission of James H. Blount, United States Commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 29.

- Kristin Zambucka (1977). The High Chiefess, Ruth Keelikolani. Kristin Zambucka Books. pp. 19–. GGKEY:2LWYXGZDYAZ.

- Roger G. Rose (1980). Hawaiʻi, the Royal Isles. Bishop Museum Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-910240-27-7.

- Michael Tsai (June 7, 2004). "The princess diaries". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- Dekneef, Matthew (March 8, 2017). "15 extraordinary Hawaii women who inspire us all. We can all learn something from these historic figures". Hawaiʻi Magazine. Honolulu. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keʻelikōlani. |

| Preceded by George Luther Kapeau |

Royal Governor of Hawaiʻi 1855–1874 |

Succeeded by Samuel Kipi |