Kawakita v. United States

Kawakita v. United States, 343 U.S. 717 (1952), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled that a dual U.S./Japanese citizen could be convicted of treason against the United States for acts performed in Japan during World War II.[1] Tomoya Kawakita, born in California to Japanese parents, was in Japan when the war broke out and stayed in Japan until the war was over. After returning to the United States, he was arrested and charged with treason for having mistreated American prisoners of war. Kawakita claimed he could not be found guilty of treason because he had lost his U.S. citizenship while in Japan, but this argument was rejected by the courts (including the Supreme Court), which ruled that he had in fact retained his U.S. citizenship during the war. Originally sentenced to death, Kawakita's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he was eventually released from prison, deported to Japan, and barred from ever returning to the United States.

| Kawakita v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 2 – April 3, 1952 Decided June 2, 1952 | |

| Full case name | Kawakita v. United States |

| Citations | 343 U.S. 717 (more) 72 S. Ct. 950; 96 L. Ed. 1249 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 96 F. Supp. 824 (S.D. Cal. 1950); 190 F.2d 506 (9th Cir. 1951); cert. granted, 342 U.S. 932 (1952). |

| Holding | |

| A U.S. citizen owes allegiance to the United States and can be punished for treason, regardless of dual nationality or citizenship, and irrespective of country of residence. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Douglas, joined by Reed, Jackson, Minton |

| Dissent | Vinson, joined by Black, Burton |

| Frankfurter and Clark took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Background

Tomoya Kawakita (川北 友弥, Kawakita Tomoya) was born in Calexico, California, on September 26, 1921, of Japanese-born parents. He was born with U.S. citizenship due to his place of birth, and also Japanese nationality via his parents. After finishing high school in Calexico in 1939, Kawakita traveled to Japan with his father (a grocer and merchant). He remained in Japan and enrolled in Meiji University in 1941. In 1943, he registered officially as a Japanese national.[2]:141[3]

Kawakita was in Japan when the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States and Japan into World War II. In 1943, he took a job as an interpreter at a mining and metal processing plant which used Allied prisoners of war (POWs) as laborers.[4] By early 1945, the population of the POW camp included about four hundred captured American troops. After the end of the war, Kawakita renewed his U.S. passport, explaining away his having registered as a Japanese national by claiming he had acted under duress. He returned to the U.S. in 1946 and enrolled at the University of Southern California.[2]:142

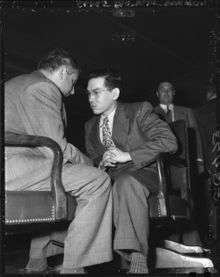

In October 1946, a former POW saw Kawakita in a Los Angeles department store and recognized him from the war. He reported this encounter to the FBI, and in June 1947, Kawakita was arrested and charged with multiple counts of treason arising from alleged abuse of American POWs.[2]:140, 141[5][6]

Trial and appeal

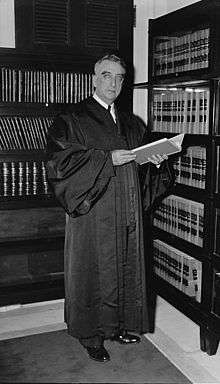

At Kawakita's trial, presided over by U.S. District Judge William C. Mathes, the defense conceded that Kawakita had acted abusively toward American POWs, but argued that his actions were relatively minor, and that in any event, they could not constitute treason against the United States because Kawakita was not a U.S. citizen at the time, having lost his U.S. citizenship when he confirmed his Japanese nationality in 1943.[2]:145 The prosecution argued that Kawakita had known he was still a U.S. citizen and still owed allegiance to the country of his birth—citing the statements he had made to consular officials when applying for a new passport as evidence that he had never intended to give up his U.S. citizenship.[2]:146

Judge Mathes's instructed the jury that if they found that Kawakita had genuinely believed he was no longer a U.S. citizen, then he must be found not guilty of treason.[6] During the course of their deliberations, the jury reported several times that they were hopelessly deadlocked, but the judge insisted each time that they continue trying to reach a unanimous verdict. In the end—on September 2, 1948—the jury found Kawakita guilty of eight of the thirteen counts of treason against him, and he was sentenced to death.[2]:155–156[3] As a consequence of his conviction for treason, Kawakita's U.S. citizenship was also revoked.[7]:431 In passing sentence, Mathes said: "Reflection leads to the conclusion that the only worthwhile use for the life of a traitor, such as this defendant has proved to be, is to serve as an example to those of weak moral fiber who may hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the United States."[5][6]

Kawakita appealed to a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which unanimously upheld the verdict and death sentence.[8] Certiorari was granted by the United States Supreme Court,[9] and oral arguments before the Supreme Court were heard on April 3, 1952.[1]

Opinion of the Court

In a 4–3 decision issued on June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court upheld Kawakita's treason conviction and death sentence.[3] The Court's opinion was written by Associate Justice William O. Douglas, joined by Associate Justices Stanley F. Reed, Robert H. Jackson, and Sherman Minton.

The Court's majority held that the jury in Kawakita's trial had been justified in concluding that he had not lost or given up his U.S. citizenship while he was in Japan during the war.[1]:720–732 The Court added that an American citizen owed allegiance to the United States, and could be found guilty of treason, no matter where he lived—even for actions committed in another country that also claimed him as a citizen.[4][1]:732–736 Further, given the flagrant nature of Kawakita's actions, the majority found that the trial judge had not acted arbitrarily in imposing a death sentence.[1]:744–745

Dissent

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson authored a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices Hugo Black and Harold H. Burton. The dissent concluded that "for over two years, [Kawakita] was consistently demonstrating his allegiance to Japan, not the United States. As a matter of law, he expatriated himself as well as that can be done." On this basis, the dissenting justices would have reversed Kawakita's treason conviction.[4][1]:746

Subsequent developments

On October 29, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower commuted Kawakita's sentence to life imprisonment plus a $10,000 fine.[10] After the commutation of his sentence, Kawakita was transferred to the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary.[10][11] Ten years later, on October 24, 1963, President John F. Kennedy—in what would be one of his last official acts before his assassination—ordered Kawakita released from prison on the condition that he leave the United States and be banned from ever returning.[3][4] Kawakita flew to Japan on December 13, 1963,[12] and reacquired Japanese citizenship upon his arrival.[7]:431 In 1978, Kawakita sought permission to travel to the United States to visit his parents' grave, but his efforts were unsuccessful.[7]:431–432 As of late 1993, he was living quietly with relatives in Japan.[13]

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 343

- Iva Toguri D'Aquino, another Japanese-American convicted of treason for actions committed during World War II

- Kanao Inouye, a Japanese-Canadian convicted of treason and executed for actions committed during World War II

References

- Kawakita v. United States, 343 U.S. 717 (1952).

- Shibusawa, Naoko (2006). America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy. Harvard University Press. pp. 140–175. ISBN 978-0-674-02348-2.

- Chuman, Frank F. (1976). The Bamboo People: The Law and Japanese-Americans. Del Mar, California: Publisher's Inc. pp. 288–290. ISBN 0-89163-013-9.

- Kim, Hyung-chan (1994). A Legal History of Asian Americans, 1790–1990. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-313-29142-X.

- "Not Worth Living". TIME Magazine. October 18, 1948. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- "POW Camp Atrocities Led to Treason Trial". Los Angeles Times. September 20, 2002. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- Kelly, H. Ansgar (1992). "Dual Nationality, the Myth of Election, and a Kinder, Gentler State Department". University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. 23: 421–464. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- Kawakita v. United States, 190 F.2d 506 (9th Cir. 1951).

- Kawakita v. United States, 342 U.S. 932 (1952) (granting certiorari).

- "Eisenhower Spares Life of U.S. Traitor" (PDF). New York Times. November 3, 1953. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- Champion, Jerry Lewis, Jr. (2011). The Fading Voices of Alcatraz. AuthorHouse. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4567-1487-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Kawakita, War Criminal, in Tokyo as a Japanese" (PDF). New York Times. December 13, 1963. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- Shimojima, Tetsuro (1993). Amerika kokka hangyakuzai アメリカ国家反逆罪 [American Treason]. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 378. ISBN 978-4-06-206120-9.

あまりにも劇的な人生を送った川北友弥氏はいま七十二歳、静かな余生を暖かな家族に囲まれて過ごしている。(Mr. Tomoya Kawakita, having lived an exceptionally dramatic life, is now 72 years old and is quietly spending his final years surrounded by his family.)

External links

- Text of Kawakita v. United States, 343 U.S. 717 (1952) is available from: Findlaw Justia Library of Congress