Kauri dieback

Kauri dieback is a forest dieback disease of the native kauri trees (Agathis australis) of New Zealand caused by the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora agathidicida.[1] Symptoms include root rot and associated rot in a collar around the base of the tree, bleeding resin, yellowing and chlorosis of the leaves followed by extensive defoliation, and finally, death.[2][3]

| Kauri dieback | |

|---|---|

| |

| A kauri tree with a bleeding trunk lesion | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Chromista |

| Phylum: | Oomycota |

| Order: | Peronosporales |

| Family: | Peronosporaceae |

| Genus: | Phytophthora |

| Species: | P. agathidicida |

| Binomial name | |

| Phytophthora agathidicida | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology

Phytophthora (from Greek φυτόν (phytón), "plant" and φθορά (phthorá), "destruction"; "the plant-destroyer") is a genus of plant-damaging oomycetes (water moulds), whose member species are capable of causing enormous economic losses on crops worldwide, as well as environmental damage in natural ecosystems.

The species name agathidicida means "kauri killer", from the genitive noun agathid- (meaning "of the kauri genus Agathis") and the Latin suffix -cide (from the verb cadere, to kill).

Disease

Symptoms of kauri dieback include root rot of both fine-feeder and larger structural roots; a collar rot lesion causing resin production ("gummosis") at the collar and lower trunk region; severe chlorosis and defoliation of the canopy; and overall crown decline. Infection by kauri dieback can rapidly kill seedlings and trees of all ages. Trees of all size classes are killed in natural forest remnants, amenity garden and park trees, and kauri plantations.[4][3][5]

Identification

Phytophthora agathidicida was first discovered on Great Barrier Island in 1972, but was initially identified from slides as a different organism, P. heveae.[6][7] Until 2006, all Phytophthora in mainland New Zealand kauri trees was considered to be Phytophthora cinnamomi; this species is extremely destructive in Western Australia, and can also infect kauri trees and produce a dieback syndrome.[8] However, it is not considered to be as serious an issue for kauri as P. agathidicida.[9]

In March 2006, entomologist Peter Maddison noticed a distinctly different infection in mature kauri in the Waitākere Ranges. Plant pathologists Ross Beever and Nick Waipara recognised this as a distinct Phytophthora species and it was named Phytophthora 'taxon Agathis' (abbreviated PTA).[10][11] It was formally named Phytophthora agathidicida in 2015.[1]

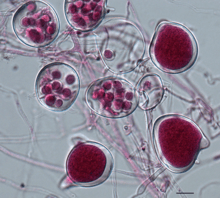

Phytophthora agathidicida is a species in the group of Phytophthora called ‘Clade 5’ which is defined by ITS DNA sequences.[12] Within Clade 5 P. agathidicida can be distinguished from the other species by DNA sequence differences and oospores that have a moderately bumpy surface. In pure agar culture the optimum growth temperature is 21.5 °C.[1]

History of spread

It is not known when the microorganism arrived in New Zealand nor the source, but the centre of diversity of Phytophthora Clade 5 is believed to be in the East Asia / Pacific region.[1] A media report of an unpublished study based on mitochondrial genomes of 17 isolates suggested that it may have existed in New Zealand for centuries and has only recently become a danger to kauri.[13] However, the 100% mortality rate and speed with which the disease has spread since 2016 suggests that it is a more recent arrival.

Another study linked infected forests with plantings from the Sweetwater Nursery in Waipoua Forest by the New Zealand Forest Service in the 1950s.[14][15] The only forest that has been regularly monitored for kauri dieback using a scientifically peer reviewed methodology is the Waitākere Ranges. Between 2011 and 2016 the infection rate of kauri trees in the ranges doubled, from 8% to 19%. In the Waitākeres 58% of large areas of kauri ecosystem over 5 hectares have some state of infection.[16][17][16][17] An independent review of the epidemiology of the Kauri study, found that "the Auckland data is of limited use if we want to conduct an analysis to identify factors associated with PTA being present".[18]

Current pathogen distribution knowledge is based on soil sampling, ground-truthing and aerial surveillance, but that has usually been limited to stands of kauri showing symptoms, at a coarse scale. Aerial surveillance has not used multi- or hyperspectral imagery or change detection.[19] It is unclear to what extent the disease spread is caused by distribution of the pathogen or whether unknown factors such as kauri resistance or P. agathidicida living on has alternative hosts influence the spread of the disease. [2]

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| March 1972 | First isolated from Great Barrier Island[20] |

| 1974 | Publication describing this isolation, initially identified as P. heveae [6] |

| March 2006 | First found in the Waitākere Ranges[10] |

| June 2006 | First documented as a possible new species with the tag name "Phytophthora taxon Agathis"[11] |

| 2008 | Declared as an "unwanted organism" under the Biosecurity Act 1993[21] |

| 2015 | Formal publication of the name "Phytophthora agathidicida" [1] |

| 2 December 2017 | Te Kawerau ā Maki place rāhui over Waitākere Ranges forest[22] |

| 5 December 2017 | Auckland Council decided not to close Waitākere Ranges[23] |

| 15 February 2018 | NZ Parliament Environment Select Committee calls for briefing on kauri dieback [24] |

| 20 February 2018 | Auckland Council votes to close entire Waitākere Ranges forests[25] |

| 18 March 2018 | DOC closed Goldie Bush[26] |

| 1 May 2018 | MPI issues "Controlled Area Notices" for the Waitākere Ranges and parts of the Hunua Ranges[27] |

| 12 May 2018 | Rahui closes Okura Bush[28] |

| June 2018 | Conservation status of kauri announced as "threatened species"[29][30] |

| 25 June 2018 | Government announces an independent panel to review kauri dieback[31] |

| July 2018 | Found in North Shore reserves[32] |

| August 2018 | Closure of all Forest and Bird reserves that have kauri [33] |

Transmission

The disease is solely soil-borne and mostly spread in infected soil carried from tree to tree. P. agathidicida spores can be carried in soil the size of a pinhead. The consensus among experts is that the predominant vector for spread of the disease is human activity. [34][17] This can be seen as 71% of the infected trees in the Waitākere Ranges are within 50 metres of public walking tracks.[16]

Phytophthora zoospores require water to germinate from the oospore, and can migrate by themselves through waterlogged soil. P. cinnamomi zoospores remain mobile for up to 10 hours, and can swim at speeds of up to 58 centimetres per hour. However, their direction of travel frequently changes, so they disperse no more than 6 cm by swimming. Consequently, long-distance dispersal of Phytophthora depends on other forms of transport.[35]

Feral pigs have been blamed for the spread of kauri dieback due to their tendency to gnaw on the roots of kauri trees, and to transport infected soil on their snouts and trotters.[36] Research in 2017 suggests the transport of infected roots via the gut of pigs is a relatively minor vector for the spread of the disease.[37]

While only kauri trees develop the characteristic dieback disease following infection, it appears that seven other native New Zealand forest plants can act as hosts for the pathogen without showing symptoms themselves. These include Dracophyllum, tanekaha (Phyllocladus trichomanoides), tall mingimingi (Leucopogon fasciculatus), rewarewa (Knightia excelsa) and Astelia trinervia.[38][16] It is thought that the community of symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi living on the roots of healthy kauri trees may help protect them from Phytophthora infection.[39]

Disease management

Auckland Regional Council (ARC) began disease surveys and information workshops in October 2006. A Joint Agency was formed in November 2008 comprising the ARC, Northland Regional Council (NRC), the Department of Conservation (DOC) and Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Biosecurity New Zealand (MAFBNZ), to develop joint communications and share information.

This was replaced in November 2009 by the National Kauri Dieback Management Programme, sponsored and funded by MAFBNZ, DOC, ARC, NRC, Environment Waikato (EW), Environment Bay of Plenty (EBoP), and tangata whenua. This began a five-year national programme of research and science oversight, surveillance, education and outreach. In 2014 this was renewed for a further 10 years.[40][41]

Footwear cleaning stations

To prevent the spread of the disease, footwear-washing stations have been set up at the entrances and exits of walking tracks. These cleaning stations provide Trigene detergent spray (also known as Sterigene) and scrubbing brushes or grates.[41][16] However, research indicates that the effectiveness and compliance is poor.[16][42][43] A 2016 report estimated that 83% of track users were failing to clean their footwear at the cleaning stations provided.[44]

DOC has since conducted research to improve the design of these cleaning stations to find out whether other designs are more likely to be used. Some improved designs were trialled during the Hilary running event in the Waitakeres and have been installed in the Waipoua forest.[16]

Closing of forests

On 2 December 2017 the local iwi Te Kawerau ā Maki placed an unofficial rāhui (traditional prohibition) over the kauri forest that covers large areas of the Waitākere Ranges to try to slow kauri dieback's spread,[45][46] but initially at least the rāhui was frequently breached by the general public.[47] The Waitākere Ranges were consequently the only large area of forest close to West Auckland that was still open to the public. On 20 February 2018, Auckland Council announced that all forested areas of the Waitākere Ranges would be closed to the public, as the rāhui had not been effective. At-risk parts of the Hunua Ranges to the south-east of Auckland were also to be closed as a preventive measure, even though kauri dieback had not yet been recorded there.[48]

Treatment

A number of compounds have been identified which are active in vitro against the pathogen responsible for kauri dieback, including common broad-spectrum antifungal agents such as copper sulfate.[49] However, there is as yet no established treatment for infected trees, with the large size of mature kauri trees and the remote location of many infected areas making any treatment challenging. Trials are underway using injections of phosphite into infected kauri trees, as this is an established treatment against Phytophthora cinnamomi in fruit trees such as avocados. Dr Ian Horner at Plant & Food Research began studying the effectiveness of phosphite in 2010.[16] Phosphite injected directly into the trunk of affected trees has been shown to stop the progress of the disease, halting sap bleeding, enabling new bark to grow and prolonging the tree's life.[16] This treatment is effective on trees of a consistent size, but research continues on effective dosages for trees of different sizes.[50][51][52][53][54] Phosphite treatment can be effective against individual kauri trees, but will not kill the Phytophthora pathogen in the soil, potentially allowing it to continue to spread to healthy trees nearby.[55]

See also

- Dutch elm disease

- Phytophthora infestans – potato blight

References

- Weir, Bevan S.; Paderes, Elsa P.; Anand, Nitish; Uchida, Janice Y.; Pennycook, Shaun R.; Bellgard, Stanley E.; Beever, Ross E. (2015). "A taxonomic revision of Phytophthora Clade 5 including two new species, Phytophthora agathidicida and P. cocois". Phytotaxa. 205 (1): 21–38. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.205.1.2. ISSN 1179-3163. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Bradshaw, R. E.; Bellgard, S. E.; Black, A.; Burns, B. R.; Gerth, M. L.; McDougal, R. L.; Scott, P. M.; Waipara, N. W.; Weir, B. S.; Williams, N. M.; Winkworth, R. C.; Ashcroft, T.; Bradley, E. L.; Dijkwel, P. P.; Guo, Y.; Lacey, R. F.; Mesarich, C. H.; Panda, P.; Horner, I. J. (6 November 2019). "research progress, cultural perspectives and knowledge gaps in the control and management of kauri dieback in New Zealand". Plant Pathology. 69 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1111/ppa.13104.

- Waipara, N.W.; Hill, S.; Hill, L.M.W.; Hough, E.G.; Horner, I.J. (2013). "Surveillance methods to determine tree health, distribution of kauri dieback disease and associated pathogens". New Zealand Plant Protection. 66: 235–241. doi:10.30843/nzpp.2013.66.5671.

- Beever, R.E., Waipara, N.W., Ramsfield, T.D., Dick, M.A., Horner, I.J. (2009). Kauri (Agathis australis) under threat from Phytophthora? Proceedings of the 4th International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) Working Party 7.02.09. Phytophthora in forests and natural ecosystems. Monterey, California, 26–31 August 2007. General Technical Report PSW-GTR-221. USDA, Forest Service, Albany, California, USA. 74–85.

- Bellgard SE, Pennycook SR, Weir BS, Ho W, Waipara NW. (2016). Phytophthora agathidicida. Forest Phytophthoras 6(1). doi: 10.5399/osu/fp.5.1.3748.

- Gadgil, Peter D (1974). "Phytophthora heveae, a pathogen of kauri" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. 1: 59–63. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Hill, Lee (2014). "Ground Truthing Survey for Kauri Dieback 2014". parliament.org.nz.

- Podger, F. D.; Newhook, F. J. (1971). "Phytophthora cinnamomi in indigenous plant communities in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 9 (4): 625–638. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1971.10430225.

- Shilton, Blair Dean (2017). The Effect of Plant Hormones on Phenolic Production in Kauri Trees (Thesis). MSc Thesis, Auckland University of Technology. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Beever, Ross. "Specimen Details". scd.landcareresearch.co.nz. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Beever, R.E., Ramsfield, T.D., Dick, M.A., Park, D., Fletcher, M.., Horner, I.J. (2006) Molecular characterisation of New Zealand isolates of the fungus Phytophthora. MAF Operational Research Report MBS304: 35pp.

- Cooke, D.E.L.; Drenth, A.; Duncan, J.M.; Wagels, G.; Brasier, C.M. (June 2000). "A Molecular Phylogeny of Phytophthora and Related Oomycetes". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 30 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1006/fgbi.2000.1202. PMID 10955905.

- Morton, Jamie (17 December 2017). "Kauri-killer may have been here for centuries". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- Beauchamp, T., & Waipara, N.W. (2014). "Surveillance and management of kauri dieback in New Zealand." Poster presented at Phytophthora in Forests and Natural Ecosystems, Proceedings of the 7th Meeting of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) Working Party S07-02-09 November 10–14, 2014, Esquel, Argentina Pp 142.

- Beachman, John (September 2017). The Introduction and Spread of Kauri Dieback Disease in New Zealand: Did Historic Forestry Operations Play a Role? (PDF). Ministry for Primary Industries. ISBN 978-1-77665-669-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- White, Rebekah (January–February 2018). "The Last of the Giants". New Zealand Geographic (149): 64–85. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Strategic Science Advisory Group (2018). "Kauri Dieback Science Plan 2018" (PDF). Kauridieback.co.nz. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020.

- "Specimen Details". scd.landcareresearch.co.nz. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Organism Details - Kauri dieback". www1.maf.govt.nz. MAF. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Rāhui ceremony performed in Waitakere ranges". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Auckland Council votes against full closure of Waitākere Ranges". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Briefing on kauri dieback". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Auckland Council votes to close entire Waitakere Ranges forests". NZ Herald. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Goldie Bush tracks closing in support of rāhui". DOC. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018. and then reopens the track in 2018. Goldies Bush managed by DOC.

- "Kauri dieback". Ministry for Primary Industries. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Okura Bush Walkway temporarily closed". DOC. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Conservation status of New Zealand indigenous vascular plants" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Smith, Simon (6 June 2018). "It's official: DOC says kauri is a threatened species". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Independent panel and kauri consultation hui launched". www.scoop.co.nz. Scoop News. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "North Shore councillor gutted, as kauri dieback found in his area for the first time". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Forest & Bird closes kauri reserves to public". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Kauri Dieback YOUR QUESTIONS ANSWERED, September 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Carlile, M.J. (1985). "The zoospore and its problems". In Ayres, P.G.; Boddy, L. (eds.). Water, Fungi and Plants: Symposium of the British Mycological Society Held at the University of Lancaster, April 1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 105–118. ISBN 978-0521106238.

- Krull, Cheryl R.; Waipara, Nick W.; Choquenot, David; Burns, Bruce R.; Gormley, Andrew M.; Stanley, Margaret C. (2013). "Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence: Feral pigs as vectors of soil-borne pathogens". Austral Ecology. 38 (5): 534–542. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2012.02444.x.

- Bassett, I.E.; Horner, I.J.; Hough, E.G.; Wolber, F.M.; Egeter, B; Stanley, M.C.; Krull, C.R. (December 2017). "Ingestion of infected roots by feral pigs provides a minor vector pathway for kauri dieback disease Phytophthora agathidicida". Forestry. 90 (5): 640–648. doi:10.1093/forestry/cpx019.

- "Ryder JM, Burns BR. (2016). What is the host range of Phytophthora agathidicida in New Zealand. Poster session presented at the meeting of New Zealand Plant Protection Vol. 69. Palmerston North" (PDF). auckland.ac.nz. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Padamsee, Mahajabeen; Johansen, Renee B.; Stuckey, S. Alexander; Williams, Stephen E.; Hooker, John E.; Burns, Bruce R.; Bellgard, Stanley E. (2016). "The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising roots and root nodules of New Zealand kauri Agathis australis". Fungal Biology. 120 (5): 807–817. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2016.01.015. PMID 27109376.

- "Working Together". Kauri Dieback Programme. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "Hygiene procedures for Kauri dieback" (PDF). kauridieback.co.nz. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "People's Panel Kauri dieback survey" (PDF). Kauri dieback. November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "DOC National Survey of New Zealanders 2013" (PDF). Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai. July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- King, Helen. "Kauri dieback: National treasure on the brink of extinction". Stuff. Fairfax New Zealand. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "Forest and Bird 'disappointed' ranges remain open". RNZ. 5 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "WAITAKERE RAHUI | Te Kawerau a Maki". tekawerau.iwi.nz. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Morton, Jamie (21 January 2016). "Thousands snubbing Waitakere Ranges rahui despite reminders by park rangers". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "Auckland Council votes to close entire Waitakere Ranges forests". 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2020 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- Lawrence, Scott A.; Armstrong, Charlotte B.; Patrick, Wayne M.; Gerth, Monica L. (19 July 2017). "High-Throughput Chemical Screening Identifies Compounds that Inhibit Different Stages of the Phytophthora agathidicida and Phytophthora cinnamomi Life Cycles". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 1340. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01340. PMC 5515820. PMID 28769905.

- Williams, Lois (30 June 2016). "Kauri dieback treatment 'shows promise'". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "Kauri dieback treatment depends on the right dose". Radio New Zealand. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "Kauri Rescue or Community Control of Kauri Dieback: Tiaki Kauri" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Horner IJ, Hough EG, Horner MB. Forest efficacy trials on phosphite for control of kauri dieback. New Zealand Plant Protection 2015; 68: 7-12 ref.9" (PDF). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Horgan, D. B. (31 July 2017). "The uptake of phosphorus acid sprays into kauri foliage". New Zealand Plant Protection. 70: 326. doi:10.30843/nzpp.2017.70.96.

- Scott, Peter; Williams, Nari (2014). "Phytophthora diseases in New Zealand forests" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Forestry. 59 (2): 14–21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

Further reading

- Care for Kauri Guide. (2010). Auckland Regional Council

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kauri dieback. |

- Kauri Dieback, Kauri Dieback Management Team

- Waitākere Rāhui

- Waitākere Rāhui, Te Kawerau a Maki

- Protect our kauri trees, Auckland Council