Karlsvärd Fortress

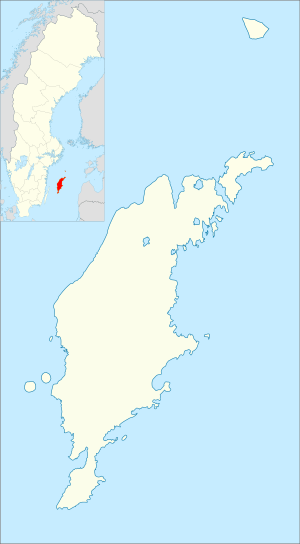

Karlsvärd Fortress (Swedish: Karlsvärds fästning) is a former fortification on the island of Enholmen near Slite on Gotland, Sweden. In its place Enholmen Fortress (Swedish: Enholmens fästning) was built in the mid-1800s. It was decommissioned in 1905 and was then used as a training ground for the coastal artillery. During the 1990s it was used as a naval mine control station before the island was demilitarized in 2011. Karlsvärd Fortress ruin is since 2015 managed by the National Property Board.

| Karlsvärd Fortress | |

|---|---|

Karlsvärds fästning | |

| Enholmen Near Slite in Sweden | |

Enholmen Fortress, 2005 | |

Karlsvärd Fortress | |

| Coordinates | 57°41′42.99″N 18°49′16.75″E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Swedish Fortifications Agency |

| Controlled by | Sweden |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | Karlsvärd Fortress (1711–1778) Enholmen Fortress (1854–1858) |

| In use | –1990s |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | Gotland garrison |

Karlsvärd Fortress

In 1650, a technical drawing of Enholmen was submitted by Quartermaster general Johan Wärnschiöldh which included a pentagonal bastion sconce with lower walls and counterscarp ditches, a drawing, which after some modifications by himself, was approved by the King in Council in 1656.[1] In 1657, the construction of the two western bastions was started. Little was done in the following years and in 1663 King Charles XI decided that the fortress would be closed.[1] In 1710, however, the Defense Commission (Defensionskommissionen) ordained that a sconce was to be built at Slite, and the County Governor Anders Sparrfelt now made a drawing in which he "corrected" the old planning and in 1711 started the work on the Karlsvärd Fortress which Enholmen's sconce was then called, and the two bastions of intermediate curtain walls were constructed.[1] Quartermaster general Magnus Palmqvist suggested, however, that instead of the completion of the "fortress", a couple of batteries and a redoubt would be built, and already in 1712, the batteries and the épaulements for the infantry and cavalry were finished. In 1719, Palmquist also considered that the construction of Karlsvärd ought not to be continued, but works constructed in 1711-12 would instead be retained, and this met with approval in the same year by Prince Frederick.[1]

In 1723, however, the resuming thought of accomplishing Karlsvärd came about, which at that time had the two south bastions in good condition, the northwestern and eastern bastions unfinished and the northern hardly begun. Now a lower sea defence across the entire stronghold was proposed. In 1739, a new drawing was made and again in 1741, then based on the 1723 plan. The construction of the actual stronghold was now continued, while a ravelin and a beach bastion was constructed and four shore batteries were built. The construction lasted until 1752, when one of Gabriel Cronstedt's prearranged draft of detached bastions in front of the curtain walls were met with approval.[1] Later Johan Bernhard Virgin suggested the construction of the shoreline under the new plan, and three bomb-free vaulted bastioned towers, but in 1756 it was decided that Karlsvärd would be fulfilled according to the 1752 decision, and colonel F. K. Wrede was commanded to draw proposals for the sea defences, which, however, should not become big or expensive.[1] The construction resumed in 1764 and then continued to 1770 when the Secret Committee (Sekreta utskottet) considered that "the so-called fortress" Karlsvärd, which construction begun during Charles X's reign, could be completed only this year, but not the shore batteries and as well as the bomb free barracks and storehouses, to which Virgin had prepared drawings, which had been upheld by 1766 Secret Committee and should now be carried out.[1]

In 1773, von Arbin was commanded to submit a "shortened" design for Karlsvärd's placing into capable defense operations for the least cost possible, and in 1779 he had prepared a design for the shore batteries with bastioned towers besides another more discursive proposal with a large dungeon, which was simultaneously submitted.[1] Further constructions were not made, and on 22 April 1788, the King in Council considered Karlsvärd, which was still unfinished, had an inappropriate plan and could not protect the country, why the fortress now was condemned as being useless, pointless and costly.[1] Major General Johan Christopher Toll was instructed to blow-up the fortifications and redirecting the defense funds to other locations. The military commander of Gotland, Michael Silvius von Hohenhausen, made a request in 1834 for an engineer officer to help in drawing the proposal for a masonry fortification on the site of Karlsvärd but this did not lead to any result.[1]

Enholmen Fortress

In 1831 cholera reached the Baltic coast and a quarantine station was established on the island. A cholera hospital was also built.[2] Slite Harbour had since olden times been fortified, but the fortification, which in the 1650s was built on Enholmen and later was called Karlsvärd was long since decayed, when the 1839 Fortification Committee suggested that a new fortification was to be established to protect the harbour.[3] Nothing was, however, done with this, but when the Crimean War broke out in 1853 and the Baltic Sea became a probable theater of war, it was quickly decided that Enholmen's once again would be fortified, and during 1854–58 two casemate fortification were built underneath the former Karlsvärd's dilapidated eastern and western fronts, exclusively for artillery defense of the two inlets to Slite.

The batteries, which were armed with four seven-inch bomb cannons m/1840 and eight 24-pounder mortar guns each, were maintained afterwards, and some wooden buildings for the accommodation of officers and crew were erected on the island, but no permanent crew was ever placed there.[3] The cholera hospital and the quarantine station was moved to the Asunden island when the island was re-fortified.[2] When the town of Slite ceased to be a naval port, the King in Council prescribed on 15 December 1905, that the cannons of Enholmen would to be sold and batteries and other buildings to be leased.[3]

Later use

During World War I and World War II, Enholmen was manned by military guards. A number of firing and observation bunkers was built during this time along the beach. After the wars, the coastal artillery in Fårösund used Enholmen as the location for emergency response exercises.[2] From the 1950s to the 1990s a naval mine control station was situated in the old fortress.[4] About fifteen meters underground were three large containers where dozens of people worked, slept and kept supplies before the station was closed in the 1990s. In 2008 it was decided that Enholmen would be sold by the Swedish Fortifications Agency.[4] During 2010-11 Enholmen was demilitarized.[2] In 2013 the Cultural Property Inquiry proposed that Enholmen would remain under state ownership.[5] The National Property Board manages Karlsvärd Fortress ruin since 2015.[2]

See also

References

- Westrin, Theodor, ed. (1910). Nordisk familjebok: konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi. Bd 13 (in Swedish) (New, rev. and richly ill. ed.). Stockholm: Nordisk familjeboks förl. pp. 1106–1107.

- "Karlsvärds fästningsruin, Enholmen" (in Swedish). National Property Board of Sweden. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Westrin, Theodor, ed. (1907). Nordisk familjebok: konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi. Bd 7 (New, rev. and richly ill. ed.). Stockholm: Nordisk familjeboks förl. pp. 631–632.

- Simonson, Jakob (2011-04-19). "Nu säljs försvarsön Enholmen" [The defense island Enholmen will now be sold]. Gotlands Allehanda (in Swedish). Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- "Enholmen" (in Swedish). Swedish Fortifications Agency. 2014-04-03. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enholmen. |

- Karlsvärd Fortress (in Swedish)

- Enholmen Fortress (in Swedish)