Kamakhya Temple

The Kamakhya Temple also known as Kamrup-Kamakhya temple,[3] is a Sakta temple dedicated to the mother goddess Kamakhya.[4] It is one of the oldest of the 51 Shakti Pithas.[5] Situated on the Nilachal Hill in western part of Guwahati city in Assam, India, it is the main temple in a complex of individual temples dedicated to the ten Mahavidyas of Saktism : Kali, Tara, Sodashi, Bhuvaneshwari, Bhairavi, Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi and Kamalatmika.[6] Among these, Tripurasundari, Matangi and Kamala reside inside the main temple whereas the other seven reside in individual temples.[7] It is an important pilgrimage destination for Hindus and especially for Tantric worshipers.

| Kamakhya Temple | |

|---|---|

Kamakhaya Temple | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| Deity | Kamakhya |

| Festivals | Ambubachi Mela |

| Location | |

| Location | Nilachal Hill, Guwahati |

| State | Assam |

| Country | India |

Location in Assam | |

| Geographic coordinates | 26.166426°N 91.705509°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Nilachal type |

| Creator | Mlechchha dynasty.[1] Rebuilt by Koch King Nara Narayan and Ahom kings |

| Completed | 8th-17th century[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Temple(s) | 6 |

| Monument(s) | 8 |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on |

| Shaktism |

|---|

|

|

Schools |

|

Festivals and temples |

|

|

In July 2015, the Supreme Court of India transferred the administration of the Temple from the Kamakhya Debutter Board to the Bordeuri Samaj.[8]

Description

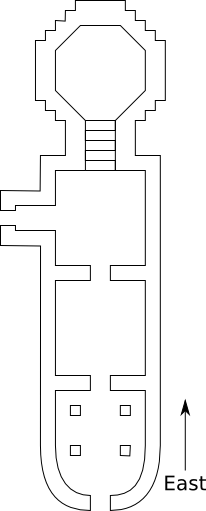

The current structural temple, built and renovated many times in the period 8th-17th century, gave rise to a hybrid indigenous style that is sometimes called the Nilachal type: a temple with a hemispherical dome on a cruciform base.[9] The temple consists of four chambers: garbhagriha and three mandapas locally called calanta, pancharatna and natamandira aligned from east to west.

Vimana

The vimana over the garbhagriha has a pancharatha plan[10] that rests on plinth moldings that are similar to the Surya Temple at Tezpur. On top of the plinths are dados from a later period which are of the Khajuraho or the Central Indian type, consisting of sunken panels alternating with pilasters.[11] The panels have delightful sculptured Ganesha and other Hindu gods and goddesses.[12] Though the lower portion is of stone, the shikhara in the shape of a polygonal beehive-like dome is made of brick, which is characteristic of temples in Kamrup.[13] The shikhara is circled by a number of minaret inspired angashikharas[14] of Bengal type charchala. The Shikhara, angashikharas and other chambers were built in the 16th century and after.

The inner sanctum within the vimana, the garbhagriha, is below ground level and consists of no image but a rock fissure in the shape of a yoni (female genital):

The garbhagriha is small, dark and reached by narrow steep stone steps. Inside the cave there is a sheet of stone that slopes downwards from both sides meeting in a yoni-like depression some 10 inches deep. This hollow is constantly filled with water from an underground perennial spring. It is the vulva-shaped depression that is worshiped as the goddess Kamakhya herself and considered as most important pitha (abode) of the Devi.[15]

The garbhaghrihas of the other temples in the Kamakhya complex follow the same structure—a yoni-shaped stone, filled with water and below ground level.

Calanta, Pancharatna, and Natamandir

The temple consists of three additional chambers. The first to the west is the calanta, a square chamber of type atchala (similar to the 1659 Radha-Vinod Temple of Bishnupur[16]). The entrance to the temple is generally via its northern door, that is of Ahom type dochala. It houses a small movable idol of the Goddess, a later addition, which explains the name.[17] The walls of this chamber contain sculpted images of Naranarayana, related inscriptions and other gods.[18] It leads into the garbhagriha via descending steps.

The pancharatna to the west of calanta is large and rectangular with a flat roof and five smaller shikharas of the same style as the main shikhara. The middle shikhara is slightly bigger than the other four in typical pancharatna style.

The natamandira extends to the west of the pancharatna with an apsidal end and ridged roof of the Ranghar type Ahom style. Its inside walls bear inscriptions from Rajeswar Singha (1759) and Gaurinath Singha (1782), which indicate the period this structure was built.[19]

History

Site of Kameikha

Historians have suggested that the Kamakhya temple is an ancient sacrificial site for an Austroasiatic tribal goddess, Kameikha (literally: old-cousin-mother), of the Khasi and Garo peoples;[20] supported by the folk lores of these very peoples.[21] The traditional accounts from Kalika Purana and the Yogini Tantra too record that the goddess Kamakhya is of Kirata origin.[22] The tradition of sacrifices continue today with devotees coming every morning with animals and birds to offer to the goddess.[23]

Ancient

The earliest historical dynasty of Kamarupa, the Varmans (350-650), as well as Xuanzang, a 7th-century Chinese traveler ignored the Kamakhya; and it is assumed that the worship at least till that period was Kirata-based beyond the brahminical ambit.[24] The first epigraphic notice of Kamakhya is found in the 9th-century Tezpur plates of Vanamalavarmadeva of the Mlechchha dynasty.[25] Since the archaeological evidence too points to a massive 8th-9th century temple,[26] it can be safely assumed that the earliest temple was constructed during the Mlechchha dynasty.[1] From the moldings of the plinth and the bandhana, the original temple was clearly of Nagara type,[27] possibly of the Malava style.

The later Palas of Kamarupa kings, from Indra Pala to Dharma Pala, were followers of the Tantrik tenet and about that period Kamakhya had become an important seat of Tantrikism. The Kalika Purana (10th century) was composed and Kamakhya soon became a renowned centre of Tantrik sacrifices, mysticism and sorcery. Mystic Buddhism, known as Vajrayana and popularly called the "Sahajia cult", too rose in prominence Kamarupa in the tenth century. It is found from Tibetan records that some of the eminent Buddhist professors in Tibet, of the tenth and the eleventh centuries, hailed from Kamarupa.

Medieval

There is a tradition that the temple was destroyed by Kalapahar, a general of Sulaiman Karrani (1566–1572). Since the date of reconstruction (1565) precedes the possible date of destruction, and since Kalapahar is not known to have ventured so far to the east, it is now believed that the temple was destroyed not by Kalapahar but during Hussein Shah's invasion of the Kamata kingdom (1498).[28]

The ruins of the temple was said to have been discovered by Vishwasingha (1515–1540), the founder of the Koch dynasty, who revived worship at the site; but it was during the reign of his son, Nara Narayan(1540–1587), that the temple reconstruction was completed in 1565. According to historical records and epigraphic evidence, the main temple was built under the supervision of Chilarai.[29] The reconstruction used material from the original temples that was lying scattered about, some of which still exists today. After two failed attempts at restoring the stone shikhara Meghamukdam, a Koch artisan, decided to take recourse to brick masonry and created the current dome.[30] Made by craftsmen and architects more familiar with Islamic architecture of Bengal, the dome became bulbous and hemispherical which was ringed by minaret-inspired angashikharas.[9] Meghamukdam's innovation—a hemispherical shikhara over a ratha base—became its own style, called Nilachal-type, and became popular with the Ahoms.[31]

Banerji (1925) records that the Koch structure was further built over by the rulers of the Ahom kingdom.[32][33] with remnants of the earlier Koch temple carefully preserved.[34][35] By the end of 1658, the Ahoms under king Jayadhvaj Singha had conquered the Kamrup and after the Battle of Itakhuli (1681) the Ahoms had uninterrupted control over the temple. The kings, who were supporters of Shaivite or Shakta continued to support the temple by rebuilding and renovating it.[36]

Rudra Singha (1696–1714) invited Krishnaram Bhattacharyya, a famous mahant of the Shakta sect who lived in Malipota, near Santipur in Nadia district, promising him the care of the Kamakhya temple to him; but it was his successor and son Siba Singha (1714–1744), on becoming the king, who fulfilled the promise. The Mahant and his successors came to be known as Parbatiya Gosains, as they resided on top of the Nilachal hill. Many Kamakhya priests and modern Saktas of Assam are either disciples or descendants of the Parbatiya Gosains, or of the Nati and Na Gosains.[39]

Worship

The Kalika Purana, an ancient work in Sanskrit describes Kamakhya as the yielder of all desires, the young bride of Shiva, and the giver of salvation. Shakti is known as Kamakhya. Tantra is basic to worship, in the precincts of this ancient temple of mother goddess Kamakhya.

The worship of all female deity in Assam symbolizes the "fusion of faiths and practices" of Aryan and non-Aryan elements in Assam.[40] The different names associated with the goddess are names of local Aryan and non-Aryan goddesses.[41] The Yogini Tantra mentions that the religion of the Yogini Pitha is of Kirata origin.[42] According to Banikanta Kakati, there existed a tradition among the priests established by Naranarayana that the Garos, a matrilineal people, offered worship at the earlier Kamakhya site by sacrificing pigs.[43]

The goddess is worshiped according to both the Vamachara (Left-Hand Path) as well as the Dakshinachara (Right-Hand Path) modes of worship.[44] Offerings to the goddess are usually flowers, but might include animal sacrifices. In general female animals are exempt from sacrifice, a rule that is relaxed during mass sacrifices.[45]

Legends

According to the Kalika Purana, Kamakhya Temple denotes the spot where Sati used to retire in secret to satisfy her amour with Shiva, and it was also the place where her yoni (genital) fell after Shiva danced with the corpse of Sati.[46] It mentions Kamakhya as one of four primary shakti peethas: the others being the Vimala Temple within the Jagannath Temple complex in Puri, Odisha; Tara Tarini) Sthana Khanda (Breasts), near Brahmapur, Odisha, and Dakhina Kalika in Kalighat, Kolkata, in the state of West Bengal, originated from the limbs of the Corpse of Mata Sati. This is not corroborated in the Devi Bhagavata, which lists 108 places associated with Sati's body, though Kamakhya finds a mention in a supplementary list.[47]

The Yogini Tantra, a latter work, ignores the origin of Kamakhya given in Kalika Purana and associates Kamakhya with the goddess Kali and emphasizes the creative symbolism of the yoni.[48]

Due to a legendary curse by the Goddess members of the Koch Bihar royal family do not visit the temple and avert their gaze when passing by.

Festivals

Being the centre for Tantra worship this temple attracts thousands of tantra devotees in an annual festival known as the Ambubachi Mela. Another annual celebration is the Manasha Puja. Durga Puja is also celebrated annually at Kamakhya during Navaratri in the autumn. This five-day festival attracts several thousand visitors.[49]

- Gallery

The adhisthana of the Kamakhya Temple

The adhisthana of the Kamakhya Temple The adhisthana of the Kamakhya temple indicates that the original temple was of Nagara style

The adhisthana of the Kamakhya temple indicates that the original temple was of Nagara style

See also

Notes

- "Along with the inscriptional and literary evidence, the archaeological remains of the Kamakhya temple, which stands on top of the Nilacala, testify that the Mlecchas gave a significant impetus to construct or reconstruct the Kamakhya temple." (Shin 2010:8)

- "it is certain that in the pit at the back of the main shrine of the temple of Kamakhya we can see the remains of at least three different periods of construction, ranging in dates from the eighth to the seventeenth century A.D." (Banerji 1925, p. 101)

- Suresh Kant Sharma, Usha Sharma,Discovery of North-East India, 2005

- "About Kamakhya Temple". Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- (Urban 2008, p. 500)

- "About Kamakhya Temple". Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- (Shin 2010, p. 4)

- Kashyap, Samudra Gupta, As SC directs the return of old order at Kamakhya, looking back, and ahead

- (Sarma 1988:124)

- (Sarma 1983, p. 47)

- (Banerji 1925, p. 101)

- "Kamakhya temple". Archived from the original on 18 March 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- (Banerji 1925, p. 100)

- (sarma 1988, p. 124)

- (Shin 2010, p. 5)

- http://www.asikolkata.in/bankura.aspx#RadhaVinod

- "There is a mobile (calanta) image of Kamakhya at the outskirt of the cave", (Goswami 1998:14)

- "Kamakhya". Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- "The date of the (Natyamandira) is not known; but it possible pertains to the period of the two inscriptions pinned to the inner wall of its wall: one of Rajesshvarasimha, 1681 Saka/1759 AD and the other to Gaurinathasimha, 1704 Saka/1782 AD." (Neog 1980:315ff)

- (Urban 2009:46)

- "To this day, in fact, many Khasi and Garo folk tales claim that Kamakhya was originally a site of their own deities." (Urban 2009:46)

- "The Kalika Purana records that the goddess Kamakhya was already there in Kamarupa even during the time of the Kiratas and immediately before Naraka started to reside there. After the Kiratas were driven out, Naraka himself became a devotee of Kamakhya, at the instance of his father Vishnu. This shows that Kamakhya was originally a tribal mother goddess. It is not unlikely that the Khasi and the Garos who are not far off from the site of Kamakhya were the original worshipers of the goddess." (Sharma 1992:319)

- "Kamakhya temple". Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- "The cult of goddess Kamakhya seems to have remained beyond the brahmanical ambit till the end of the seventh century. The ruling family of Kamarupa during the Bhauma-Varmans dynasty did not pay any attention to her." (Shin 2010, p. 7)

- "The first epigraphic references to the goddess Kamakhya are found in the Tezpur plates and the Parbatiya plates of Vanamaladeva in the mid-ninth century." (Shin 2010, p. 7)

- "The steps which lead from the landing stage on the river to the top of Nilachala hill at Kamakhya are composed of immense blocks of stone some of which were evidently taken from a temple of great antiquity. The carvings on these slabs indicate that they must belong to the seventh or eighth century A.D., being slightly later than the carving on the stone door-frame at Dah Parbatiya. Some of the capitals of pillars are of such immense size that they indicate that the structure to which they belonged must have been as gigantic as the temple of the Sun god at Tezpur." (Banerji 1925, p. 100)

- (Saraswati 1990:454)

- Karrani's expedition against the Koch kingdom under the command of Kalapahar took place in 1568, after Chilarai had the temple rebuilt in 1565. Kalapahar was in seize of the Koch capital when he was recalled to put down a rebellion in Orissa—and there is no evidence that he ventured further east to the Guwahati region. Therefore, Kalapahar, Karrani's general, was not the person who destroyed the Kamakhya temple. (Nath 1989, pp. 68–71)

- (Sarkar 1992:16). It is said that Viswa Simha revived worship at Kamakhya. According to an inscription in the temple, his son Chilarai built the temple during the reign of Naranarayana, the king of Koch Bihar and the son of Viswa Simha, in the year 1565.

- (Sarma 1988:123)

- (Sarma 1981:185)

- "This temple was built on the ruins of another structure erected by king Sukladhvaja or Naranarayana, the first king and founder of the Koch dynasty of Cooch Bihar, whose inscription is still carefully preserved inside the mandapa." (Banerji 1925, p. 100)

- The temple of the goddess Kali or Kamakhya on the top of the hill was built during the domination of the Ahoms." (Banerji 1925, p. 100)

- Encyclopaedia Indica - Volume 2 - 1981 -Page 562 Statues of King Nara Narayan and his brother, general Chilarai were also enshrined on an inside wall of the temple.

- Tattvālokaḥ - Volume 29 - 2006 - p. 18 It was rebuilt by the Koch king, Nara Narayan. Statues of the king and his brother Sukladev and an inscription about them are found in the temple

- (Sarma 1983, p. 39)

- "(The Nrityamandira's) outer surfaces are decorated with figures in high relief as in a gallery. They include a wide range of subjects ranging from gods and goddesses to Ganas, Betalas and other demigods. The walls have niches with cusped arches to hold these pieces in rows separated by pilasters at regular intervals." (Das Gupta 1959:488)

- "One of (Rajeshwar Singha's) notable achievements is the successful erection of the natamandapa of the Kamakhya temple..." (Sarma 1981:179-180)

- Gait, Edward A History of Assam, 1905, pp. 172–73

- Satish Bhattacharyya in the Publishers' Note, Kakati 1989.

- Kakati suspects that Kama of Kamakhya is of extra-Aryan origin, and cites correspondence with Austric formations: Kamoi, Kamoit, Komin, Kamet etc. (Kakati 1989, p. 38)

- Kakati 1989, p9: Yogini Tantra (2/9/13) siddhesi yogini pithe dharmah kairatajah matah.

- (Kakati 1989, p. 37)

- (Kakati 1989, p. 45)

- Kakati mentions that the list of animals that are fit for sacrifice as given in the Kalika Purana and the Yogini Tantra are made up of animals that are sacrificed by different tribal groups in the region.(Kakati 1989, p. 65)

- Kakati 1989, p34

- Kakati, 1989, p42

- Kakati, 1989 p35

- "Kamakhya Temple". Retrieved 12 September 2006.

References

- Banerji, R D (1925), "Kamakhya", Annual Report 1924-25, Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 100–101, retrieved 2 March 2013CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Choudhury, Nishipad Dev (1997), "Ahom Patronage on the Development of Art and Architecture in Lower Assam", Journal of the Assam Research Society, 33 (2): 59–67CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Das Gupta, Rajatananda (1959). "An Architectural Survey of the Kamakhya Temple". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 22: 483–492. JSTOR 44304345.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kakati, Banikanta (1989), The Mother Goddess Kamakhya, Guwahati: Publication BoardCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gait, Edward (1905) A History of Assam

- Goswami, Kali Prasad (1998). Kamakhya Temple. Guwahati: Kāmākhyā Mandira.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neog, Maheshwar (1980). Early History of the Vaishnava Faith and Movement in Assam. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saraswati, S K (1990), "Art", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam: Ancient Period, I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 423–471CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkar, J. N. (1992), "Chapter I: The Sources", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 1–34

- Sarma, P (1983). "A Study of Temple Architecture under Ahoms". Journal of Assam Research Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, P C (1988). Architecture of Assam. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, Pradip Chandra (1981). A study of the temple architecture of Assam from the Gupta period to the end of the Ahom rule (PhD). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Sharma, M M (1990), "Religion", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam: Ancient Period, I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 302–345CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2010). "Yoni, Yoginis and Mahavidyas : Feminine Divinities from Early Medieval Kamarupa to Medieval Koch Behar". Studies in History. 26 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1177/025764301002600101.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Urban, Hugh B. (2008). "Matrix of Power: Tantra, Kingship, and Sacrifice in the Worship of Mother Goddess Kāmākhyā". The Journal of South Asian Studies. Routledge. 31 (3): 500–534. doi:10.1080/00856400802441946.

- Urban, Hugh (2009), The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 9780857715869CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kamakhya Temple. |