Kaman K-MAX

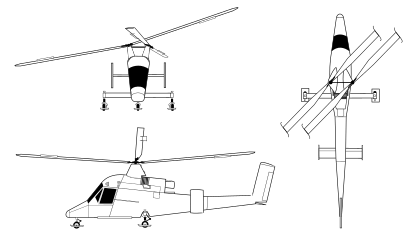

The Kaman K-MAX (company designation K-1200) is an American helicopter with intermeshing rotors (synchropter) by Kaman Aircraft. It is optimized for external cargo load operations, and is able to lift a payload of over 6,000 pounds (2,722 kg), which is more than the helicopter's empty weight. An unmanned aerial vehicle version with optional remote control has been developed and evaluated in extended practical service in the war in Afghanistan.

| K-1200 K-MAX | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Kaman K-1200 from Rotex aviation | |

| Role | Medium lift helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Kaman Aircraft |

| First flight | December 23, 1991 |

| Status | In production |

| Produced | 1991–2003, 2015–present |

After being out of production for more than a decade, in June 2015 Kaman announced it was restarting production of the K-MAX due to it receiving ten commercial orders.[1] The first flight of a K-MAX from the restarted production took place in May 2017 and the first new-build since 2003 was delivered on July 13, 2017 for firefighting in China.

Development

In 1947 Anton Flettner, a German aero-engineer, was brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.[2] He was the developer of the two earlier synchropter designs from Germany during World War II: the Flettner Fl 265 which pioneered the synchropter layout, and the slightly later Flettner Fl 282 Kolibri ("Hummingbird"), intended for eventual production. Both designs used the principle of counter-rotating side-by-side intermeshing rotors, as the means to solve the problem of torque compensation, normally countered in single–rotor helicopters by a tail rotor, fenestron, NOTAR, or vented blower exhaust. Flettner remained in the United States and became the chief designer of the Kaman company.[3] He started to design new helicopters, using the Flettner double rotor.

The K-MAX series is the latest in a long line of Kaman synchropters, the most famous of which is the HH-43 Huskie. The first turbine-powered helicopter was also a Kaman synchropter.[4]

The K-1200 K-MAX "aerial truck" is the world's first helicopter specifically designed, tested, and certified for repetitive external lift operations and vertical reference flight (Kaman received IFR Certification in 1999), an important feature for external load work. Other rotorcraft used for these tasks are adapted from general-purpose helicopters, or those intended to primarily carry passengers or internal cargo. The K-MAX can lift almost twice as much as the Bell 205 using a different version of the same engine.[5] The aircraft's narrow, wedge-shaped profile and bulging side windows give the pilot a good view of the load looking out from either side of the aircraft.[6]

The transmission has a reduction ratio of 24:1 in three stages, and is designed for unlimited life.[7] The rotor blades (which turn in opposite directions)[5] are built with a wooden spar and fiberglass trailing edge sections. Wood was chosen for its damage tolerance and fatigue resistance; and to take advantage of field experience and qualification data amassed from a similar spar on the HH-43 Huskie helicopter, built for the U.S. Air Force in the 1950s and 1960s.[8] The pilot controls blade pitch with tubes running inside the mast and rotor blades to move servo flaps that pitch the blades,[9] reducing required force and avoiding the added weight, cost and maintenance of hydraulic controls.[5]

The K-MAX relies on two primary advantages of synchropters over conventional helicopters: The increased efficiency compared to conventional rotor-lift technology; and the synchropter's natural tendency to hover. This increases stability, especially for precision work in placing suspended loads. At the same time, the synchropter is more responsive to pilot control inputs, making it possible to easily swing a load, or to scatter seed, chemicals, or water over a larger area.

Thirty-eight K-1200 K-MAX helicopters had been built by 2015.[10] As of January 2015, 11 of these were not airworthy or had been written off in accidents and five were in storage at Kaman;[11][12] and in March 2015 the number of operational K-MAXs was 21.[5] The production line was shut down in 2003.[13]

Unmanned version

Kaman had been developing the Unmanned K-MAX since 1998. In March 2007, Kaman and Lockheed Martin (Team K-MAX) signed a Strategic Relationship Agreement (SRA) to pursue U.S. DoD opportunities.[14][15] An unmanned mostly autonomously flying, optionally remote controlled and optionally piloted vehicle (OPV) version, the K-MAX Unmanned Multi-Mission Helicopter was developed for hazardous missions. It can be used in combat to deliver supplies to the battlefield, as well as civilian situations involving chemical, biological, or radiological hazards. A prototype of this was shown in 2008 for potential military heavy-lift resupply use,[16] and again in 2010.[17] In December 2010 the Naval Air Systems Command awarded a $46 million contract to Kaman for two aircraft,[18] and in 2011 they completed a five-day Quick Reaction Assessment.[19]

Restart of production line

In February 2014, Kaman revisited resuming K-MAX production, having recently received over 20 inquiries for firefighting, logging and industry transport requirements as well as requests for the military unmanned version. Ten firm orders convinced Kaman to put the design back into production again.[20][21][22] As of 2014, the K-MAX line had flown 300,000 hours and cost $1,200 per flight hour to operate.[22]

At Heli-Expo 2015 in Orlando, Kaman reported it continued toward reopening the production line.[23] Kaman received deposits and the assembly line was restarted in January 2017.[24] Kaman test flew the first K-MAX from restarted production on May 12, 2017.[25][26]

The first new-build since 2003 was delivered on July 13, 2017 to Kaman's Chinese sales agent Lectern Aviation, which will deliver it to Guangdong Juxiang General Aviation, Guangdong Province for firefighting with the second to be delivered the following week.[27] Due to production scheduling, Kaman needed to decide in 2017 whether to extend production beyond the first 10, and Kaman made the decision in June 2017 to produce a further 10 aircraft, reaching into at least 2019.[28][29]

From 2020, Kaman should offer an optionally piloted variant to commercial customers to fly into dangerous zones like wildfires or natural disasters, and for long operation with no pilot rest, up to 100h until mandatory inspections. After FAA certification, it could be fitted on new and used helicopters outside the factory and builds on the three-year autonomy experiment in Afghanistan with the US Marine Corps since 2011.[30]

Operational history

A K-MAX has been used for demolition work by having a wrecking ball as a slung load.[31]

In December 2011, an unmanned K-MAX was reported to be at work in Afghanistan.[32] On 17 December 2011, the U. S. Marine Corps conducted the first unmanned aerial system cargo delivery in a combat zone using the unmanned K-MAX, moving about 3,500 pounds of food and supplies to troops at Combat Outpost Payne.[33] A third unmanned K-MAX in the U.S. was tested in 2012 to deliver cargo to a small homing beacon with three-meter precision.[34] As of February 2013, the K-MAX had delivered two million pounds of cargo in 600 unmanned missions over more than 700 flight hours.[35]

.jpg)

On July 31, 2012, Lockheed announced a second service extension for the K-MAX in Afghanistan for the Marines,[36] then on 18 March 2013 the Marine Corps extended its use of the unmanned K-MAX helicopters indefinitely, keeping the two aircraft in use "until otherwise directed". At the time of the announcement, they had flown over 1,000 missions and hauled over three million pounds of supplies. Assessments for their use after deployment were being studied.[37] The unmanned K-MAX has won awards from Popular Science and Aviation Week & Space Technology,[38] and was nominated for the 2012 Collier Trophy.[39]

On June 5, 2013, one of the unmanned K-MAX helicopters crashed in Afghanistan while resupplying Marines. No injuries occurred and the crash was investigated. Pilot error was ruled out, as the aircraft was flying autonomously to a predetermined point. The crash happened during the final stages of cargo delivery.[40] Operational flights of the remaining unmanned K-MAX were suspended following the crash, with the Navy saying it could resume flying by late August. Swing load was seen as the prime cause.[41] The investigation determined that the crash was not caused by mechanical problems,[42] but by unexpected tailwinds. As the helicopter was making the delivery, it experienced tailwinds instead of headwinds, causing it to begin oscillating. Operators employed a weathervane effect to try and regain control, but its 2,000 lb load began to swing, which exacerbated the effect and caused it to contact the ground. The crash report determined that it could have been prevented if pilots intervened earlier and mission planners received updated weather reports; diverging conditions and insufficient programming meant it could not recover on its own and required human intervention.[43]

At the 2013 Paris Air Show, Kaman promoted the unmanned K-MAX to foreign buyers. Several countries reportedly expressed interest in the system.[44] The K-MAX supporting Marines in Afghanistan was planned to remain in use there until at least August 2014. The Marine Corps was looking into acquiring the unmanned K-MAX as a program of record, and the United States Army was also looking into it to determine cost-effectiveness. In theater, the aircraft performed most missions at night and successfully lifted loads of up to 4,500 lb (2,000 kg). Hook-ups of equipment were performed in concert with individuals on the ground, but Lockheed was looking into performing this action automatically through a device mounted atop the package that the helicopter can hook up to by itself; this feature was demonstrated in 2013.[45] Other features were being examined, including the ability to be automatically re-routed in flight, and to fly in formation with other aircraft.[46] The unmanned K-MAX was successfully able to deliver 30,000 lb (13,600 kg) of cargo in one day over the course of six missions (average 5,000 lb (2,270 kg) transported cargo per mission). Lockheed and Kaman discussed the purchasing of 16 helicopters with the Navy and Marine Corps for a baseline start to a program.[42]

The unmanned K-MAX competed with the Boeing H-6U Little Bird for the Marine Corps unmanned lift/ISR capability.[47] In April 2014, Marines at Quantico announced they successfully landed an unmanned K-MAX, as well as a Little Bird, autonomously using a hand held mini-tablet. The helicopters were equipped with Autonomous Aerial Cargo/Utility System (AACUS) technology, which combines advanced algorithms with LIDAR and electro-optical/infrared sensors to enable a user to select a point to land the helicopter at an unprepared landing site.[48] The Office of Naval Research selected Aurora Flight Sciences and the Unmanned Little Bird to complete development of the prototype AACUS system, but Lockheed continued to promote the K-MAX and develop autonomous cargo delivery systems.[49]

Both unmanned K-MAX helicopters in use by the Marine Corps returned to the U.S. in May 2014, when the Corps determined that they were no longer needed to support missions in Afghanistan. After deploying in December 2011, originally planned for six months, they stayed for almost three years and lifted 2,250 tons of cargo. The aircraft were sent to Lockheed's Owego facility in New York, while the service contemplated the possibility of turning the unmanned K-MAX from a proof-of-concept project into a program of record. Formal requirements for unmanned aerial cargo delivery are being written to address expected future threats, including electronic attack, cyber warfare, and effective hostile fire; these were avoided in Afghanistan quickly and cheaply by flying at night at high altitudes against an enemy with no signal degradation capabilities.[50][51] Officials assessed the K-MAX helicopter that crashed and planned to repair it in 2015. The helicopters, ground control stations, and additional equipment are stored at Lockheed's facility in Owego.[52] The two unmanned K-MAXs, designated CQ-24A, were to be moved to a Marine Corps base in Arizona by the end of September 2015 to develop tactics and operations concepts to inform an official program of record for a cargo UAV.[53]

Lockheed Martin demonstrated a fire fighting version in November 2014,[23] and again in October 2015, when it delivered over 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg) water in one hour.[54][55] A casualty evacuation exercise was performed in March 2015 in coordination with an unmanned ground vehicle and mission planning system.[56] A medic launched the UGV to evaluate the casualty, used a tablet to call in and automatically land the K-MAX, then strapped a mannequin to a seat aboard the helicopter.[57]

Operators

- Skywork Helicopters Ltd.[61]

- Central Copters, Inc.[66]

- Columbia Basin Helicopters (1 on order)[67]

- Helicopter Express[68]

- HeliQwest International[69]

- ROTAK Helicopter Services[70]

- Swanson Group Aviation[71]

- Timberline Helicopters, Inc.[72]

- United States Marine Corps[73]

Specifications (K-MAX)

Data from K-MAX performance and specs[74][75]

General characteristics

- Crew: one

- Capacity: 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) external load

- Length: 51 ft 10 in (15.8 m)

- Rotor diameter: 48 ft 3 in (14.71 m)

- Height: 13 ft 7 in (4.14 m)

- Empty weight: 5,145 lb (2,334 kg)

- Useful load: 6,855 lb (3,109 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 12,000 lb (5,400 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Honeywell T53-17 turboshaft, 1,341 kW (1,800 shp), flat rated to 1,118 kW (1,500 shp) for take-off / 1,350 shp in flight[76][77])

Performance

- Maximum speed: 100 knots (185 km/h, 115 mph)

- Cruise speed: 80 knots (148 km/h, 92 mph)

- Range: 267 nmi (495 km, 307 miles)

- Service ceiling: 15,000 feet[5] (4,600 m)

- Fuel consumption: 85 gallons (322 litre)/hour[22]

See also

| Images | |

|---|---|

| Video | |

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

- Kaman restarts K-Max production on new commercial orders Archived June 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal

- Boyne, Walter J. (2011). How the Helicopter Changed Modern Warfare. Pelican Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 1-58980-700-6.

- ""Anton Flettner"; Hubschraubermuseum Bückeburg". Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- "Twin Turborotor Helicopter" Archived September 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Popular Mechanics, August 1954, p. 139.

- Head, Elan (March 9, 2015). "Going Solo". Vertical Magazine. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Gray, Peter (June 26, 1996). "Long – Lining". Flightglobal. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- 'K-MAX Intermeshing Rotor Drive System' 53rd Annual Forum Proc., AHH, 1997.

- 'Composites take off ... in some civil helicopters.' Archived September 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine 1 March 2005. Retrieved: 26 June 2011.

- Chandler, Jay. "Advanced rotor designs break conventional helicopter speed restrictions (p. 2) Archived July 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine" . ProPilotMag, September 2012. Accessed: 10 May 2014. Archive 2

- The Kaman K-MAX Production list Archived April 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine by Markus Herzig

- The Kaman K-MAX Current Status Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine SwissHeli.com by Markus Herzig

- http://www.sust.admin.ch/pdfs/AV-berichte/%5B%5D/2142_e.pdf

- Padfield, R. Randall (March 2012). "Civil Tiltrotor and K-Max Aerial Truck Back in the Saddle?" (PDF). AINonline.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- Kaman Aerospace Archived June 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Lockheed Martin K-MAX". Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Lockheed Martin And Kaman Aerospace Demonstrate Unmanned Supply Helicopter To U.S. Army". Archived from the original on October 10, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- "Team K-MAX demonstrates successful unmanned Helicopter Cargo resupply to U.S. Marine Corps" Archived November 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Lockheed Martin press release, 8 February 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- "Lockheed Martin awarded $45.8 million for unmanned KMAX" Archived December 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Defense Update, 6 December 2010. Accessed: 11 December 2010.

- "Lockheed Martin/Kaman K-MAX Completes US Navy Unmanned Cargo Assessment" Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, 8 September 2011. Accessed: 9 September 2011.

- "Kaman Aerospace Soliciting Interest in New K-MAX Production" (Press release). Kaman. February 25, 2014.

- Scott Gourley (February 27, 2014). "Heli-Expo 2014: Kaman looks to restart K-MAX production". rotorhub. Shephardmedia. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- Elan Head (April 2014). "Production potential". Vertical Magazine. p. 44. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- Head, Elan (March 15, 2015). "Kaman still aiming to restart K-MAX production". Vertical Magazine. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Trimble, Stephen (January 17, 2017). "Kaman inducts first K-Max into re-opened assembly plant". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- "Kaman announces first new K-MAX flight" (Press release). Kaman. May 19, 2017. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Grady, Mary (May 23, 2017). "First Flight For New K-Max". AVweb. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Mark Phelps (July 17, 2017). "Kaman Delivers First New-build K-Max in Fourteen Years". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (June 14, 2017). "Kaman authorises second batch of K-Max helicopter production". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

a decision within two months on whether to extend production beyond the first 10 aircraft. A decision had to be made before June to avoid a break in the production system.

- Mark Huber (June 9, 2017). "Kaman Delivering First New-production K-Max". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Garrett Reim (March 7, 2019). "Kaman to offer optionally piloted K-Max by 2020". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on March 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Karman III, John R. (August 18, 2008). "Demolition precedes new construction for Ursuline schools". Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- John Roach. "Robotic helicopters at work in Afghanistan". Future of Technology, MSNBC. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- "Unmanned helicopter makes first delivery for Marines in Afghanistan". USMC. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- "Beacon improves UAV’s cargo-delivery accuracy" Marine Corps Times, 8 July 2012. Retrieved: 9 July 2012.

- McLeary, Paul. "K-MAX Chugging Along in Afghanistan" Aviation Week, 3 February 2012. Accessed: 4 February 2012.

- U.S. Marine Corps to Keep K-MAX Unmanned Cargo Re-Supply Helicopter in Theater for Second Deployment Extension Archived January 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – Lockheed press release, July 31, 2012

- US Marines extend K-MAX unmanned helicopter's use in Afghanistan Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine – Reuters.com, 18 March 2013

- "Unmanned K-MAX Wins Top Innovation Honors, USMC Praise". HeliHub. January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- "Unmanned K-MAX is nominee for Collier Trophy". HeliHub. February 11, 2013. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- Unmanned Marine helo crashes in Afghanistan Archived June 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – Militarytimes.com, 13 June 2013

- US Navy set to resume K-MAX flights Archived August 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 14 August 2013

- Marines Work to Extend K-MAX in Afghanistan Through 2014 Archived March 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – Defensetech.org, 25 September 2013

- Tailwinds caused K-Max crash in Afghanistan Archived August 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – Strategicdefenseintelligence.com, 11 August 2014

- K-MAX looks to lift overseas sales Archived January 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 18 June 2013

- Stephen Trimble. "Lockheed tests K-MAX cargo enhancement Archived December 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine" – Flightglobal.com, 18 November 2013. Accessed: 18 November 2013.

- Lockheed seeks more autonomy for unmanned K-MAX Archived September 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 11 September 2013

- USMC Unmanned Lift Competition Taking Shape – Defensenews.com, 25 September 2013

- Marines Fly Helicopters With Mini-Tablet Archived April 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – DoDBuzz.com, 5 April 2014

- Aurora beats Lockheed bid to develop iPad-based UAS controller Archived January 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 6 May 2014

- K-MAX RoboCopter Comes Home To Uncertain Future Archived August 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – Breakingdefense.com, 24 July 2014

- K-MAX returns from Afghan deployment Archived July 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 25 July 2014

- K-MAX cargo drone home from Afghanistan, headed to storage Archived August 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine – Militarytimes.com, 2 August 2014

- U.S. Marines take next step toward cargo UAS acquisition Archived August 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 4 August 2015

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- K-Max carries out US federal government firefighting tests Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal

- "Neya Systems Awarded Phase III SBIR to Demonstrate VTOL UAV Control" Archived January 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Neya Systems, 4 April 2014.

- Lockheed Tests Casualty Evacuation Mission with K-MAX Drone Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine – Nationaldefensemagazine.org, 1 May 2015

- "Heliqwest Fleet". heliqwest.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- "Canadian Civil Aircraft Register". Transport Canada. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- "colombian army aviation". helis.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "Skywork Helicopters". skyworkhelicopters.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Peruvian police anti-drug order boosts K-MAX, p. 21". flightglobal.com. January 29, 2001. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- Markus Herzig. "HB-XHJ". Swissheli.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "HELOG". helis.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- Markus Herzig. "Swiss Helicopters – Current Fleetlist". Swissheli.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- "Central Copters Inc". Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- "Kaman Receives K-MAX Order From Columbia Basin Helicopters" (Press release). Helitech International. London: Kaman Aerosystems. October 3, 2017. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- "A shut and open case Archived November 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" RotorHub, August/September 2015 – Volume 9, Number 4

- "Heliqwest Fleet". heliqwest.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- "Helicopter | Anchorage | ROTAK Helicopter Services". Helicopter | Anchorage | ROTAK Helicopter Services. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Swanson group aviation". DNA Web Agency. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "Timberline Helicopters". Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "U.S. Marine Corp K-MAX". helis.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "K-MAX Performance and Specs". Kaman Aircraft. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- The Kaman K-MAX Specifications Archived April 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine SwissHeli.com by Markus Herzig

- "Kaman K-1200 "K-MAX"". Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- "Kaman K–1200 FAA Approved Rotorcraft Flight Manual Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", p. 1–4. Kaman, February 17, 2004. Retrieved: October 2, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kaman K-MAX. |