Kallar (caste)

Kallar (or Kallan, formerly spelled as Colleries) is one of the three related castes of southern India which constitute the Mukkulathor confederacy.[1] The Kallar, along with the Maravar and Agamudayar, constitute a united social caste on the basis of parallel professions, though their locations and heritages are wholly separate from one another.

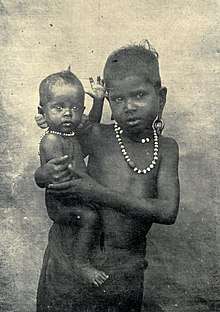

Kallar children with dilated earlobes, formerly a common practice | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Folk Hinduism |

Etymology

Kallar is a Tamil language word meaning thief. Their history has included periods of banditry.[2] Other proposed etymological origins include "black skinned", "hero", and "toddy-tappers".[3]

The anthropologist Susan Bayly notes that the name Kallar, as with that of Maravar, was a title bestowed by Tamil poligars (warrior-chiefs) on pastoral peasants who acted as their armed retainers. The majority of those poligars, who during the late 17th- and 18th-centuries controlled much of the Telugu region as well as the Tamil area, had themselves come from the Kallar, Maravar and Vatuka communities.[4] Kallar is synonymous with the western Indian term, Koli, having connotations of thievery but also of upland pastoralism.[5] According to Bayly, Kallar should be considered a "title of rural groups in Tamil Nadu with warrior-pastoralist ancestral traditions".[6]

Caste origins

Bayly notes that the Kallar and Maravar identities as a caste, rather than as a title, "... were clearly not ancient facts of life in the Tamil Nadu region. Insofar as these people of the turbulent poligar country really did become castes, their bonds of affinity were shaped in the relatively recent past".[5] Prior to the late 18th-century, their exposure to Brahmanic Hinduism, the concept of varna and practices such as endogamy that define the Indian caste system was minimal. Thereafter, the evolution as a caste developed as a result of various influences, including increased interaction with other groups as a consequence of jungle clearances, state-building and ideological shifts.[4]

The Thondaiman kings of the erstwhile Pudukottai kingdom hailed from the Kallar caste.[7]

Culture

Among the traditional customs of the Kallar noted by colonial officials was the use of the "collery stick" (Tamil: valai tādi, kallartādi), a bent throwing stick or "false boomerang" which could be thrown up to 100 yards (91 m).[8] Writing in 1957, Louis Dumont noted that despite the weapon's frequent mention in literature, it had disappeared amongst the Piramalai Kallar.[9]

Diet

The Kallar were traditionally a non-vegetarian people,[10] though a 1970s survey of Tamil Nadu indicated that 30% of Kallar surveyed, though non-vegetarian, refrained from eating fish after puberty.[11] Meat, though present in the Kallar diet, was not frequently eaten but restricted to Saturday nights and festival days. Even so, this small amount of meat was sufficient to affect perceptions of Kallar social status.[12]

Martial arts

The Kallars traditionally practised a Tamil martial art variously known as Adimurai, chinna adi and varna ati. In recent years, since 1958, these have been referred to as Southern-style Kalaripayattu, although they are distinct from the ancient martial art of Kalaripayattu itself that was historically the style found in Kerala.[13]

References

- Price, Pamela G. (1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 62, 87, 193. ISBN 978-0-52155-247-9.

- Dirks, Nicholas B. (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780472081875.

- Kuppuram, G. (1988). India through the ages: history, art, culture, and religion, Volume 1. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 366.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Nicholas B. Dirks. The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press, 1993 - Social Science - 430 pages. p. 130.

- Sir Henry Yule; Arthur Coke Burnell (1903). Hobson-Jobson: a glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological, historical, geographical and discursive. J. Murray. pp. 236–. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Dumont, Louis; Stern, A.; Moffatt, Michael (1986). A South Indian subcaste: social organization and religion of the Pramalai Kallar. Oxford University Press.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf. Criminal gods and demon devotees: essays on the guardians of popular Hinduism. p. 21.

- Robson, John R. K. Food, ecology, and culture: readings in the anthropology of dietary practices. p. 98.

- Dumont, Louis; Stern, A.; Moffatt, Michael (1986). A South Indian subcaste: social organization and religion of the Pramalai Kallar. Oxford University Press.

- Zarilli, Philip B. (2001). "India". In Green, Thomas A. (ed.). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia. A – L. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.