Jvari Monastery

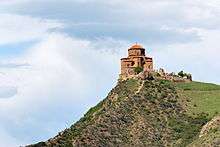

Jvari Monastery (Georgian: ჯვრის მონასტერი) is a sixth-century Georgian Orthodox monastery near Mtskheta, eastern Georgia. Along with other historic structures of Mtskheta, it is listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO. Jvari is a rare case of the Early Medieval Georgian church that survived to the present day almost unchanged. The church became the founder of its type, the Jvari type of church architecture, prevalent in Georgia and Armenia. Built atop of Jvari Mount (656 m a.s.l.), the monastery is an example of harmonious connection with the natural environment, characteristic to Georgian architecture.

- The name of this monastery translated as the "Monastery of the Cross". For the Georgian monastery in Jerusalem with the same name, see Monastery of the Cross.

| Jvari Monastery | |

|---|---|

Jvari Monastery | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Georgian Orthodox |

| Location | |

| Location | Mtskheta, Georgia |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Tetraconch |

| Completed | 586-605 AD, by King Stephen I of Kartli (Iberia) |

| Height (max) | 25 m |

| Official name: Historical Monuments of Mtskheta | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1994 (18th session) |

| Reference no. | 708 |

| Region | Europe |

History

Jvari Monastery stands on the rocky mountaintop at the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers, overlooking the town of Mtskheta, which was formerly the capital of the Kingdom of Iberia.

According to traditional accounts, on this location in the early 4th century Saint Nino, a female evangelist credited with converting King Mirian III of Iberia to Christianity, erected a large wooden (or vine) cross on the site of a pagan temple. The cross was reportedly able to work miracles and therefore drew pilgrims from all over the Caucasus. A small church was erected over the remnants of the wooden cross in c.545 during the rule of Guaram I, and named the "Small Church of Jvari", which can still be seen adjacent to the main church from the north.

The small church did not satisfy the needs of popular pilgrimage site, and the present building, or "Great Church of Jvari", is generally held to have been built between 590 and 605 by Guaram's son Erismtavari Stepanoz I. This is based on the Jvari inscriptions on its facade which mentions the principal builders of the church: Stephanos the patricius, Demetrius the hypatos, and Adarnase the hypatos. Professor Cyril Toumanoff disagrees with this view, identifying these individuals as Stepanoz II, Demetre (brother of Stepanoz I), and Adarnase II (son of Stepanoz II), respectively.[1] Nino's cross remained inside of the church, and its original postament can still be found here.

In 914, during the Sajid invasion of Georgia, the church was burned by Arabs, but it managed to survive with only minor repairments.

The importance of Jvari complex increased over time and attracted many pilgrims. In the late Middle Ages, the complex was fortified by a stone wall and gate, remnants of which still survive. During the Soviet period, the church was preserved as a national monument, but access was rendered difficult by tight security at a nearby military base. After the independence of Georgia, the building was restored to active religious use. Jvari was listed together with other monuments of Mtskheta in 1994 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

However, over the centuries the structures suffered damage from rain and wind erosion and inadequate maintenance. Jvari was listed in the 2004 World Monuments Watch list by the World Monuments Fund.

Architecture

The Jvari church was built on the very margin of a cliff, with its western facade nearly hanging over a precipice, where it was strengthened by a controforse wall. The temple looks like growing from the mountain, which was obviously the architect's plan. Jvari is one of the best examples of harmonic relation of architecture with nature.[2]

It has two entrances, from the north and from the south. The building has the shape of a cross, prolonged from east to west, with each arm ended by semicircular apses.[3] The Jvari church is an early example of a "four-apsed church with four niches"[4] domed tetraconch. Between the four apses are three-quarter cylindrical niches, which are open to the central space, and the transition from the square central bay to the base of the dome's drum is effected through three rows of squinches, an architectural achievement of its time. The lower row is made of four larger squinches, the two upper of smaller squinches, and finally the row of 32 facets, holding the dome. Thus, the dome rests on the walls, not on pillars, like in later churches, creating a single, entire space, and illusion of large size, although the church is less than 25 m high. Presence of high transitionary niches between the main space and the four small rooms is another trick of the architect, who wanted to diminish the contrast between large and small spaces.[5] The Jvari church had a great impact on the further development of Georgian architecture and served as a model for many other churches.

The leading element of the building, the dome, has an 8-faceted tholobate. Under the dome, near the center of the interior, stands a postament, surrounded by an octagon, important artistic addition, which was originally at the base of Nino's cross, but now holds a new wooden cross. The four cylindrical niches between the apses lead to four rooms: two in the eastern part, the altar and the sacristy, and two in the western, prayer rooms for the ruler (northwestern) and for women (southwestern). A writing above the latter room tells that its construction was funded by unknown Timistia. It also has a flat relief with depiction of the Ascension of Christ. Internal walls were originally covered with ashlar, and later plastered and painted in frescos, little of which survived.

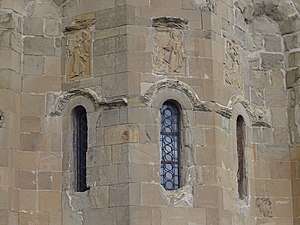

Varied bas-relief sculptures with Hellenistic and Sassanian influences decorate its external observable eastern and southern façades, some of which are accompanied by explanatory inscriptions in Georgian Asomtavruli script. The entrance tympanum on the southern façade is adorned with a relief of the Glorification of the Cross, the same façade also shows an Ascension of Christ, a rather prevalent theme in Early Christian art. The cross, which is a traditional Bolnisi cross, is held by two angels. Northern façade is closed by a small earlier built church, as well as the western, visible from afar, are not decorated. Each window on the eastern façade has a decorative knob. Each of the three facets of the eastern apsis has a bas-relief, depicting rulers and noblemen. The left shows Demetre, the brother of Stepanoz I. The central depicts Stepanoz I in front of the Christ, which is also explained on the writing. The right bas-relief has Adrnerse the Hypatos with his son and archangels Gabriel and Michael flying above, but the identity is unclear, and some connect it with Adarnase I or Adarnase II. Another bas-relief, with Stepanoz II in front of the Christ, is found on the southern apsis. Possibly, the church architect, a kneeling figure, is depicted on the southern facet of the tholobate.

The small Guaram's church, quadrangular in general proportions, has a cross-shaped interior. It is connected to a portal from the north, with the entrance to the church here and from the south. The church walls are covered by well-processed blocks. The conch was covered in mosaic, but only a fragment remains. A decorated niche is meant for the katolikos of Georgia. The southern entrance is decorated by capitals with ornamental leaves. A portal also connects the two churches.

The monastery complex is surrounded by remnants of walls with towers. The entrance with the gate was from the east.

Uncertainty over, and debate about, the date of the church's construction have assumed nationalist undertones in Georgia and Armenia, with the prize being which nation can claim to have invented the "four-apsed church with four niches" form.

.jpg) Demetre the Hypatos. Eastern façade.

Demetre the Hypatos. Eastern façade. Stepanoz I in front of the Christ. Eastern façade.

Stepanoz I in front of the Christ. Eastern façade..jpg) Adarnase with son. Eastern façade.

Adarnase with son. Eastern façade.- Stepanoz II in front of the Christ. Southern façade.

Threats

Erosion is playing its part to deteriorate the monastery, with its stone blocks being degraded by wind and acidic rain.[6]

Gallery

Panoramic view of the church and surroundings.

Panoramic view of the church and surroundings. Mtskheta, Jvari monastery, view from South.

Mtskheta, Jvari monastery, view from South. Georgia, Mtskheta, Jvari monastery. Stone carved relief on outer South wall.

Georgia, Mtskheta, Jvari monastery. Stone carved relief on outer South wall. Jvari monastery, Mtskheta. Interior view with big wooden cross.

Jvari monastery, Mtskheta. Interior view with big wooden cross. View of the cross and dome.

View of the cross and dome. Jvari monastery, Mtskheta, Georgia. A tree with cloth ribbons and small pieces of canvas tied to its branches.

Jvari monastery, Mtskheta, Georgia. A tree with cloth ribbons and small pieces of canvas tied to its branches. View of Jvari monastery

View of Jvari monastery

Notes

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003), Studies In Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts And Eurasian Contexts, p. 344. Peeters Bvba ISBN 90-429-1318-5.

- Джанберидзе Н., Мачабели К. (1981) Тбилиси. Мцхета. Москва: Искусство, 255 c. (In Russian)

- Закарая, П. (1983) Памятники Восточной Грузии. Искусство, Москва, 376 с. (In Russian)

- J-M. Thierry & P. Donabedian, "Armenian Art" p67.

- Джанберидзе Н., Мачабели К. (1981) Тбилиси. Мцхета. Москва: Искусство, 255 c. (In Russian)

- ICOMOS Heritage at Risk 2006/2007: Jvari (Holy Cross) Monastery in Mtskheta

References

- Abashidze, Irakli. Ed. Georgian Encyclopedia. Vol. IX. Tbilisi, Georgia: 1985.

- ALTER, Alexandre. A la croisée des temps. Edilivre Publications: Paris, - (novel)- 2012. ISBN 978-2-332-46141-4

- Amiranashvili, Shalva. History of Georgian Art. Khelovneba: Tbilisi, Georgia: 1961.

- Джанберидзе Н., Мачабели К. (1981) Тбилиси. Мцхета. Москва: Искусство, 255 c. (In Russian)

- Grigol Khantsteli. Chronicles of Georgia.

- Закарая, П. (1983) Памятники Восточной Грузии. Искусство, Москва, 376 с. (In Russian)

- Rosen, Roger. Georgia: A Sovereign Country of the Caucasus. Odyssey Publications: Hong Kong, 1999. ISBN 962-217-748-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jvari monastery. |