Jungle Fever

Jungle Fever is a 1991 American romantic drama film written, produced and directed by Spike Lee. The film stars Wesley Snipes, Annabella Sciorra, Lee, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Samuel L. Jackson, Lonette McKee, John Turturro, Frank Vincent, Halle Berry, Tim Robbins, and Anthony Quinn, and is Lee's fifth feature-length film. Jungle Fever explores the beginning and end of an extramarital interracial relationship against the urban backdrop of the streets of New York City in the late 1980s. The film received positive reviews, with particular praise for Samuel L. Jackson's performance.

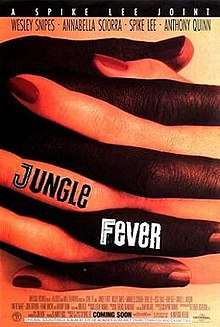

| Jungle Fever | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Spike Lee |

| Produced by | Spike Lee |

| Written by | Spike Lee |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Ernest Dickerson |

| Edited by | Sam Pollard |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $14 million[1] |

| Box office | $43.9 million[1] |

Plot

Flipper Purify (Wesley Snipes), a successful and happily married architect from Harlem, is married to Drew (Lonette McKee), who works as a buyer at Bloomingdales. Together, they have a young daughter, Ming (Veronica Timbers). At work, Flipper discovers that an Italian-American woman named Angie Tucci (Annabella Sciorra) has been hired as a temp and his secretary. Initially Flipper is upset that he is the only person of colour working at Mast & Covington but after being told employees are hired according to their ability and not race, he relents.

Angie lives in Bensonhurst with her abusive father, Mike (Frank Vincent), and her two brothers, Charlie (David Dundara) and Jimmy (Michael Imperioli). Angie and her boyfriend Paulie Carbone (John Turturro) have been dating since . Paulie runs a corner and lives with his elderly widowed father, Lou (Anthony Quinn). Angie feels suffocated in her home life; every night when she returns home from work she is expected to cook for her father and two brothers.

Flipper and Angie begin to spend many nights in the working late, and one night they have sex. The sexual encounter begins their tumultuous relationship. Flipper wakes up the next morning ignoring his daughter. Afterwards, Flipper demands to be promoted to partner at the company but gets delayed by his superiors, Jerry (Tim Robbins) and Leslie (Brad Dourif), to which he responds by resigning and having plans to start his own firm. Eventually, Flipper admits his infidelity to his longtime friend, Cyrus (Spike Lee).

Cyrus criticizes Flipper for having an affair with a white woman, referring to the cause as "jungle fever " - an attraction borne of sexualized racial myths rather than love. Flipper pleads with Cyrus not to tell anyone, including his wife. Angie's friends are shocked when Angie tells them she is having a relationship with a black man.

Drew learns about Flipper's affair, through Cyrus' wife, Vera (Veronica Webb) after Cyrus told Vera about Flipper's infidelity and throws him out of their home. Flipper moves in temporarily with his father, Southern Baptist preacher The Good Reverend Purify (Ossie Davis) and mother, Lucinda Purify (Ruby Dee). Later, Angie comes home to a severe and brutal beating with a from her father when word gets out that she is dating a black man after one of Angie's friends tells one of Angie's brothers.

Flipper tries to reconcile with Drew, but pushes his luck by making an assumption. She orders him to leave her place of business. Being multiracial, Drew feels Flipper was attracted to her for being half-white, but is now unfaithful to her because she is half-black and that Flipper was searching for a white, light-skinned woman as he was a successful black man. Flipper and Angie find an apartment in Greenwich Village and move in together. As a couple, they encounter discrimination such as being insulted by a waitress (Queen Latifah) in a restaurant , chastisement from The Good Reverend , and financial issues.

After some play fighting, Flipper gets restrained by a policeman who receives a call that he was attacking Angie. The incompatibility of Flipper and Angie's relationship is compounded by Flipper's feelings for Drew and Ming, and the fact Angie wants to have children of her own. Eventually the couple break up - echoing what Cyrus told him earlier, Flipper tells Angie their relationship has been based on sexual racial myths and not love, but Angie does not concede the point.

Things begin to turn worse for Flipper when his crack-addicted older brother Gator (Samuel L. Jackson) - who has been constantly pestering Flipper and his family for money - steals and sells Lucinda's TV for crack. Flipper's family refuses to give Gator money because he has repeatedly spent their money on crack. Flipper searches all over Harlem for Gator, finding him in a crack house. He finally gives up on his brother and cuts him off, (not before attacking Vivian after hearing about what happened to the TV) telling him that he is not allowed to ask anyone in his family for money and that no one in the family will give him any more money.

Rebelling, Gator arrives at his parents' to ask for money and, after Lucinda refuses him, begins to ransack the home. Gator's erratic behavior leads to an altercation with both of his parents that ends with The Good Reverend shooting him in the groin region, proclaiming his son to be "evil and better off dead". Gator collapses, screaming in pain, before he finally dies in a weeping Lucinda's arms with The Good Reverend watching remorsefully.

Another subject the film focuses on is Paulie, the former fiancé of Angie. Paulie is taunted by his racist Italian-American friends for having lost his girlfriend to a black man. Paulie asks one of his customers - a friendly black woman named Orin Goode (Tyra Ferrell) - on a date. This angers Paulie's father, whom Paulie defies. On his way to meet Orin, Paulie is surrounded and assaulted viciously by his customers for his attempt at an interracial relationship. Although beaten, Paulie still arrives at Orin's for their date. Frankie, one of the attackers despises black people although loves Public Enemy.

Angie later is accepted back into her father's home and Flipper tries to mend his relationship with Drew but is unsuccessful. He talks to his daughter as she is in bed. As Flipper leaves his, a young crack-addicted prostitute propositions him, calling him "daddy"; in response, Flipper throws his arms around her and cries out in torment.

In a deleted scene, Flipper is driving a car with Cyrus inside when Frankie asks him to pull over. Eventually, Flipper takes off while Frankie stares at the open space in shock.

Cast

- Wesley Snipes as Flipper Purify[2]

- Annabella Sciorra as Angie Tucci

- Spike Lee as Cyrus

- Ossie Davis as The Good Reverend Doctor Purify

- Ruby Dee as Lucinda Purify

- Samuel L. Jackson as "Gator" Purify[3]

- Lonette McKee as Drew Purify

- John Turturro as Paulie Carbone

- Frank Vincent as Mike Tucci

- Anthony Quinn as Lou Carbone

- Halle Berry as Vivian

- Tyra Ferrell as Orin Goode

- Veronica Webb as Vera

- Michael Imperioli as James Tucci

- Nicholas Turturro as Vinny

- Michael Badalucco as Frankie Botz

- Debi Mazar as Denise

- Tim Robbins as Jerry

- Brad Dourif as Leslie

- Theresa Randle as Inez

- Queen Latifah as Waitress

Themes

Racism

Lee dedicated the film to Yusuf Hawkins.[4][5] Hawkins was killed on August 23, 1989, in Bensonhurst, New York by Italian-Americans who believed the youth was involved with a white girl in the neighborhood, though he was actually in the neighborhood to inquire about a used car for sale. According to the New York Daily News, "the attack had more to do with race than romance".[6]

Drugs

In the film, Flipper's brother, Gator, is a crack addict. He is constantly pestering his family members for money. His father has disowned him, but his mother and Flipper still occasionally give him money when he asks.[7][8][9][10]

In an interview with Esquire, Jackson explains that he was able to effectively play the crack addict Gator because he had just gotten out of rehab for his own crack addiction. Because of his personal experience with the drug, Jackson was able to help Lee make Gator's character seem more realistic by helping establish Gator's antics and visibility in the film.[11]

Soundtrack

The film's soundtrack was by Stevie Wonder and was released by Motown Records. Although the album was created for the movie, it was released before the movie's premiere in May 1991. It has 11 tracks, all of which are written by Stevie Wonder, except for one. Though some believe that Wonder's album was unappealing, others believed that it was his best work in years.[12]

Reception

Critical response

The film garnered mostly positive reviews from critics, with particular praise for Samuel L. Jackson's performance as crack addict Gator, which is often considered to be his breakout role.[13][8][9][10] On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 81% based on reviews from 48 critics. The site's consensus states: "Jungle Fever finds Spike Lee tackling timely sociopolitical themes in typically provocative style, even if the result is sometimes ambitious to a fault."[14]

Accolades

- 1991 Cannes Film Festival

- Best Supporting Actor: Samuel L. Jackson[15]

- Prize of the Ecumenical Jury (Special Mention)

- Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards

- Best Supporting Actor: Samuel L. Jackson

- National Board of Review

- 10th Best Film of the Year

- New York Film Critics Circle Awards

- Best Supporting Actor: Samuel L. Jackson

- Political Film Society Human Rights Award

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[16]

References

- "Jungle Fever (1989)". Box Office Mojo.

- "Jungle Fever". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- Williams, Lena (1991-06-09). "UP AND COMING; Samuel L. Jackson: Out of Lee's 'Jungle,' Into the Limelight". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- https://slate.com/culture/2014/07/spike-lees-opening-credits-sequences-titles-for-movies-do-the-right-thing-da-sweet-blood-of-jesus-jungle-fever-and-more-are-among-the-best-parts-of-the-movie.html

- "5 Things To Know About 'Storm Over Brooklyn,' a New Doc About Yusuf Hawkins". Essence.

- "Yusef Hawkins, a black man, is killed by a white mob in 1989". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- "Spike Lee Cools Off but His 'Fever' Doesn't". The Los Angeles Times. 1989-05-17. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- Freedman, Samuel G. (1991-06-02). "FILM; Love and Hate in Black and White". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- Stephen Hunter (June 7, 1991). "Spike Lee's 'Jungle Fever' seethes with realities of interracial relationships". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- Roger Ebert (June 7, 1991). "Jungle Fever". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- JOHN H. RICHARDSON (2010-12-15). "Samuel L. Jackson: What I've Learned". Esquire. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- "Jungle Fever - Stevie Wonder | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- "Spike Lee Cools Off but His 'Fever' Doesn't". The Los Angeles Times. 1991-05-17. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- "Jungle Fever (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "Festival de Cannes: Jungle Fever". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.